Summary

-

1.

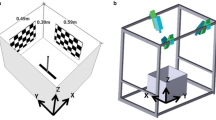

Males of many species of hoverfly hover in one spot ready to pursue passing objects, presumably in order to catch a mate. We have filmed two of the larger species as they begin their pursuit of an approaching projectile shot at them from a peashooter. Flies do not turn and fly towards the projectile as they would if they were tracking (Land and Collett, 1974). Instead they adopt an interception path, accelerating at a uniform rate (30–35 m · s−2) approximately in the direction in which the target is moving (Fig. 1).

-

2.

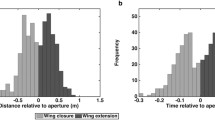

If the projectile is made to reverse direction, the male does not respond to the change in the target's course for about 90 ms (Fig. 2). Thus, in contrast to the situation later (Fig. 3), the start of a pursuit is not under continuous sensory control. The fly selects its course when it first sees the target and maintains its interception path as an open-loop response.

-

3.

Males only need to catch conspecifics and can thus assume that their quarry has a typical speed and, since it is of a uniform size, will be detected at a predetermined distance. These assumptions mean that the approach angle of the target at the moment of first sighting can be specified by the image velocity of the target across the retina (\(\dot \theta _e \)). Since the male also “knows” its own acceleration, the direction of flight which will enable it to intercept the target can also be specified in terms of the initial position (θ e) and velocity (\(\dot \theta _e \)) of the target image (Figs. 6 and 7).

-

4.

We show that interception should occur if the male obeys the simple rule that the size of the turn it makes (Δφ) is given by

$$\Delta \phi \simeq \theta _e - 0.1{\text{ }}\dot \theta _e \pm 180^\circ $$.

Our data indicate that the initial turns of the males do obey this rule (Fig. 8), and that males are “designed” to catch females travelling at about 8 m · s−1.

-

5.

If males are calibrated to catch targets of a particular size and speed, they will be unable to intercept projectiles that are very different in these respects. When large, slowly moving projectiles are launched to pass by the fly, its attempted interception path is predictably inappropriate (Fig. 9).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barmack, N.H.: Modification of eye movements by instantaneous changes in the velocity of visual targets. Vision Res.10, 1431–1441 (1970)

Collett, T.S., Land, M.F.: Visual control of flight behaviour in the hoverflySyritta pipiens L. J. comp. Physiol.99, 1–66 (1975)

Land, M.F., Collett, T.S.: Chasing behaviour of houseflies (Fannia cannicularis). A description and analysis. J. comp. Physiol.89, 331–357 (1974)

Reichardt, W., Poggio, T.: Visual control of orientation behaviour in the fly Part 1. A quantitative analysis. Quart. Rev. Biophys.9, 311–375 (1976)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We thank the SRC for financial support.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collett, T.S., Land, M.F. How hoverflies compute interception courses. J. Comp. Physiol. 125, 191–204 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00656597

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00656597