Abstract

Objective

The incretin effect is attenuated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, partly as a result of impaired beta cell responsiveness to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). The aim of the present study was to investigate whether 4 weeks of near-normalisation of the blood glucose level could improve insulin responses to GIP and GLP-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Eight obese patients with type 2 diabetes with poor glycaemic control (HbA1c 8.6 ± 1.3%), were investigated before and after 4 weeks of near-normalisation of blood glucose (mean blood glucose 7.4 ± 1.2 mmol/l) using insulin treatment. Before and after insulin treatment the participants underwent three hyperglycaemic clamps (15 mmol/l) with infusion of GLP-1, GIP or saline. Insulin responses were evaluated as the incremental area under the plasma C-peptide curve.

Results

Before and after near-normalisation of blood glucose, the C-peptide responses did not differ during the early phase of insulin secretion (0–10 min). The late phase C-peptide response (10–120 min) increased during GIP infusion from 33.0 ± 8.5 to 103.9 ± 24.2 (nmol/l) × (110 min)−1 (p < 0.05) and during GLP-1 infusion from 48.7 ± 11.8 to 126.6 ± 32.5 (nmol/l) × (110 min)−1 (p < 0.05), whereas during saline infusion the late-phase response did not differ before vs after near-normalisation of blood glucose (40.2 ± 11.2 vs 46.5 ± 12.7 [nmol/l] × [110 min]−1).

Conclusions

Near-normalisation of blood glucose for 4 weeks improves beta cell responsiveness to both GLP-1 and GIP by a factor of three to four. No effect was found on beta cell responsiveness to glucose alone.

ClinicalTrials.gov ID no.: NCT 00612950

Funding: This study was supported by The Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Medical Science Research Foundation for Copenhagen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The progressive nature of type 2 diabetes is mainly a result of a continuous decline in beta cell function [1, 2], resulting in deterioration of glycaemic control over a period of years [3]. The first-phase insulin response to intravenous glucose is severely already impaired in the early stages of the disease, whereas the beta cell response to non-glucose secretagogues is preserved, although reduced compared with healthy controls [2]. Postprandial insulin secretion is primarily regulated by blood glucose levels and the incretin hormones, glucose-dependent insulinotropic hormone (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Both are important mediators of the incretin effect, i.e. the greater increase in insulin secretion after oral than intravenous glucose administration [4]. In patients with type 2 diabetes the incretin effect is markedly reduced, primarily because of a defect in beta cell sensitivity to GIP, while the insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 is preserved, although reduced [5–8]. Moreover, several studies have shown reduced secretion of the incretin hormones in patients with type 2 diabetes [5, 9, 10]. Both hormones are secreted from endocrine mucosal cells in the small intestine in response to ingestion of nutrients, lipids and simple carbohydrates being the most potent stimulators [11, 12]. They are rapidly eliminated from the circulation; their initial clearance is mediated by the ubiquitous enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-IV) [12, 13], but their elimination rates are similar in patients and healthy controls [14, 15]. The progressive deterioration in beta cell function over time in patients with type 2 diabetes [16, 17], characterised by a beta cell secretory defect and decreased beta cell mass, results at least partly from prolonged exposure of beta cells to high glucose levels, referred to as glucotoxicity [1, 18–24]. We hypothesised that the impaired incretin effect in patients with type 2 diabetes may be a result of chronic exposure to elevated blood glucose levels, giving the possibility that glucotoxicity is a partly reversible phenomenon; a reduction in diabetic hyperglycaemia might be expected to restore, at least partly, the defective insulinotropic action of the incretin hormones. Therefore, the aim of the present investigation was to study whether 4 weeks of near-normalisation of the blood glucose concentration could restore the insulin response to GIP and improve the response to GLP-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes. To estimate both early- and late-phase insulin and C-peptide responses, we used a hyperglycaemic clamp at 15 mmol/l for 120 min [7].

The infusion rates of GLP-1 and GIP were chosen in order to obtain physiological elevations of plasma concentrations to document the impaired ability of physiological amounts (corresponding to the levels of endogenous hormone secretion) to influence islet secretion before the treatment, as well as to make sure that any improvement after the treatment would be physiologically relevant.

Methods

Subjects

Eight male patients with type 2 diabetes were studied. Patient characteristics were as follows (mean ± SD): age, 52 ± 9 years; BMI, 31.1 ± 3.9 kg/m2; HbA1c, 8.6 ± 1.3%; plasma fructosamine, 327 ± 83 μmol/l; blood glucose concentration, 13.8 ± 4.3 mmol/l (evaluated from seven-point blood glucose profiles during three consecutive days before the start of insulin treatment); duration of diabetes, 4.5 ± 3.6 years. For comparison, eight matched healthy control participants were studied: age 51 ± 9 years; BMI 30.8 ± 3.9 kg/m2; HbA1c 5.3 ± 0.2%; fructosamine 215 ± 17 μmol/l; blood glucose concentration 4.5 ± 0.6 mmol/l. All patients were treated with oral hypoglycaemic agents (biguanides and/or sulfonylureas) and none showed any overt diabetic complications or any other medical illnesses. Glucose-lowering drugs were discontinued at least 3 weeks before each experiment. None of the healthy control participants had a family history of diabetes, and all had normal oral glucose tolerance, as assessed by 75 g OGTT. All participants were negative with regard to islet cell autoantibodies and glutamate decarboxylase 65 autoantibodies, and all gave written consent to participate after receiving oral and written information. The study design was approved by the Scientific–Ethical Committee of the county of Copenhagen, and the study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki II. The patients were investigated as described below, both before and after 4 weeks of insulin treatment. Before initiation of insulin treatment, glycaemic control was evaluated from blood glucose measurements seven times daily for 3 days, before and 1.5 h after each main meal and at 22:00 hours. Additionally, HbA1c and fructosamine were measured.

Experimental procedure

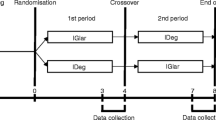

The patients were investigated during 2 h hyperglycaemic clamps (15 mmol/l) with continuous infusion of GLP-1, GIP or saline in randomised order. Patients were investigated both before and after 4 weeks of insulin treatment, giving a total of six experimental days, whereas the healthy control participants were investigated only once (three experimental days). After a 10 h overnight fast, the participants were studied in the recumbent position with two cannulas inserted into cubital veins, one for infusion and one for blood sampling. At time zero (0 min), 50% glucose (wt/vol.) was infused for 1 min to increase plasma glucose to 15 mmol/l (the amount of glucose given was calculated as follows: [15 mmol/l − fasting plasma glucose] × 35 mg glucose × body weight in kg). Plasma glucose was kept at 15 mmol/l by continuous infusion of 20% glucose (wt/vol.), which was adjusted every 5 min according to bedside measurements of plasma glucose. After 3 min, a patient-blinded continuous infusion of GLP-1 (0.5 pmol kg−1 min−1), GIP (1.5 pmol kg−1 min−1) or saline (25 ml/h) was initiated. Blood was sampled 15, 10, 0 min before and 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105 and 120 min after the i.v. bolus of glucose. Blood was sampled into fluoride tubes for glucose analysis, and into heparin tubes and EDTA tubes for hormone analysis. Tubes were immediately cooled on ice and centrifuged at 4°C within 20 min. Plasma was stored at −20°C until analysis (plasma for insulin and C-peptide analysis was stored at −80°C).

Insulin treatment

After completion of the initial studies (three clamps), each of the patients with diabetes was treated with multiple insulin injections. Insulin therapy included administration of a fast-acting insulin analogue before each meal as well as basal insulin coverage by intermediate-acting (NPH) insulin administered twice daily, based on self-monitored blood glucose using a OneTouch Ultra Bood Glucose Meter (LifeScan, Johnson and Johnson, Milpitas, CA, USA). During the first week, blood glucose levels were monitored daily before main meals and 1.5 h after each meal (seven times daily), to achieve a targeted fasting and pre-meal blood glucose level of 5 mmol/l (without incurring unacceptable risk of hypoglycaemia) and a targeted postprandial blood glucose level below 8 mmol/l. During the next 3 weeks of treatment, the participants measured blood glucose seven times daily, twice every week and four times daily on the other 5 weekdays. To achieve the targeted blood glucose levels, insulin adjustment was made before each insulin injection. A hypoglycaemia event was defined as a plasma glucose reading below 3.1 mmol/l or a requirement for third-party assistance.

Peptides

Synthetic GLP-1 (7–36) amide and synthetic GIP were purchased from PolyPeptide Laboratories (Wolfenbüttel, Germany). The same lot numbers of GLP-1 and GIP were used in all studies. The peptides were dissolved in sterilised water containing 2% (wt/vol.) human serum albumin (Human Albumin; Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark; it was guaranteed to be free of hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibodies and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies) and subjected to sterile filtration. Appropriate amounts of peptide for each experimental participant were dispensed into glass ampoules and stored frozen (−20°C) under sterile conditions until the day of the experiment. The peptide was demonstrated to be >97% pure and identical to the natural human peptides by HPLC, mass and sequence analysis.

Analyses

Plasma glucose concentrations were measured during the experiments by the glucose oxidase method, using a glucose analyser (YSI 2300 STAT Plus Analyzer; Yellow Springs Instrument, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Plasma insulin and C-peptide concentrations were measured by Autodelphia automatic fluoroimmunoassay (Wallec, Turku, Finland). Plasma samples were assayed for total GLP-1 immunoreactivity as described previously [25], using a radioimmunoassay (antiserum no. 89390) specific for the C-terminal of the GLP-1 molecule and reacting equally with intact GLP-1 and the primary (N-terminally truncated) metabolite. Total GIP was measured using the C-terminally directed antiserum R65 [26, 27], which reacts fully with intact GIP and the N-terminally truncated metabolite GIP (3-42). The assays had detection limits of <2 pmol/l and an intra-assay coefficient of variation of approximately 6%. The glucagon assay was directed against the C-terminal of the glucagon molecule (antibody code no. 4305) and therefore measured glucagon of mainly pancreatic origin [28].

Statistical analysis and calculations

All results are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. First-phase insulin secretion (0–10 min) and second-phase insulin secretion (10–120 min) were calculated from the AUC using the trapezoidal rule, and are presented as the incremental values if nothing else is stated. The significance of differences between patients and the healthy control group was tested using the Mann–Whitney U test, and for within-participant comparisons the Wilcoxon test for paired differences was used. Within-group comparisons, comparing the results of the different days, were tested using one-way ANOVA. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Insulin treatment

After the 3 week washout period, the patients were in poor glycaemic control with an HbA1c of 8.6 ± 1.3% (mean ± SD), a fructosamine concentration of 327 ± 83 μmol/l and a blood glucose concentration of 13.8 ± 4.3 mmol/l, evaluated from the seven-point blood glucose profile obtained during 3 days. After initiation of insulin treatment a rapid improvement in glycaemic control was observed, and the mean blood glucose during the last 7 days of insulin treatment was 7.4 ± 0.4 mmol/l (Fig. 1). HbA1c (7.5 ± 1.1%) and fructosamine (249 ± 39 μmol/l) were significantly reduced after 4 weeks of insulin treatment. The mean total daily dose of insulin was 76 ± 5 IU. Two of the participants had hypoglycaemic episodes. One participant had two hypoglycaemic episodes with plasma glucose below 3.1 mmol/l and the other had three episodes. No major hypoglycaemic events requiring third-party assistance were reported.

Glucose

There was no difference in fasting plasma glucose between the three experimental days (GLP-1, GIP, saline), either before (11.9 ± 1.0, 11.8 ± 1.1 and 11.8 ± 1.0 mmol/l respectively) or after (7.5 ± 0.4, 7.1 ± 0.4 and 6.2 ± 0.4 mmol/l) insulin treatment. However, fasting plasma glucose was significantly reduced on the three experimental days after insulin treatment, but was nevertheless still significantly higher on all study days than in the healthy control participants. Plasma glucose concentrations increased immediately after the bolus glucose injection and reached a stable plateau at 15.5 ± 0.1 mmol/l, which was similar on all the experimental days, both within and between groups (not significant). The total amount of glucose needed to maintain the hyperglycaemic clamp during the GLP-1, GIP and saline days was higher in the healthy control participants compared with the patients, both before and after insulin treatment (p < 0.05). In the participants with type 2 diabetes no difference was seen between the three experimental days, either before or after insulin treatment (not significant). However, significantly more glucose was needed in the patients to maintain the clamp after the insulin treatment on all three experimental days (p < 0.05; data not shown).

GLP-1 and GIP

During GLP-1 infusion the plasma GLP-1 concentrations increased and after 20 min reached a plateau of 41 ± 7, 45 ± 6 and 46 ± 11 pmol/l before insulin treatment, after insulin treatment and in the healthy controls, respectively (no significant difference between groups). During the GIP infusions a plateau was reached at approximately 90 and 120 min, with plasma GIP concentrations of 136 ± 15, 132 ± 15 and 146 ± 10 pmol/l before insulin treatment, after insulin treatment and in the healthy controls, respectively, with no significant different between the 3 days.

Insulin and C-peptide

Fasting plasma insulin and fasting plasma C-peptide were similar on the saline, GLP-1 and GIP days, both before and after the insulin treatment in the patients, and did not differ from those observed in the healthy control participants, except for fasting plasma C-peptide on the GIP day after insulin treatment (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Plasma insulin (a, b) and C-peptide (c, d) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (a, c) and healthy control participants (b, d) during GLP-1 infusions before (white squares) and after (black squares) insulin treatment, during GIP infusions before (white circles) and after (black circles) insulin treatment, and during saline infusions before (white triangles) and after (black triangles) insulin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes, and during GLP-1 (black squares), GIP (black circles) and saline (black triangles) infusions in healthy control participants. Dashed lines represent the early phase plasma insulin or C-peptide response (1–10 min) to the glucose clamp. Differences between study days are given in Table 1

The AUCs for the early-phase insulin responses are listed in Table 1. As illustrated, there was no significant initial first-phase plasma insulin or C-peptide response (0–10 min) to the glucose clamp on any day in the patients with type 2 diabetes, before and after insulin treatment. In the healthy control participants, there was a clear, initial (0–10 min) plasma insulin and C-peptide response to the clamp, but this was not influenced by infusion of GLP-1 or GIP. These initial (0–10 min) insulin and C-peptide responses were clearly larger in the healthy control participants than in the patients after insulin therapy (p < 0.05). During the remaining 110 min of the clamp (10–120 min), plasma insulin and C-peptide responses to the clamps were not influenced by infusion of GLP-1 or GIP before insulin treatment. Therefore, the insulin responses did not differ on the three study days (Table 1). After insulin treatment the insulin responses were equally and significantly enhanced by a factor of 3 on the GLP-1 and GIP study days compared with before insulin treatment (Table 1, Fig. 2). The C-peptide response to glucose alone was not significantly different before and after insulin treatment. In the healthy control participants, GLP-1 and GIP had equal effects in increasing insulin and C-peptide concentrations compared with saline alone (Table 1). Both responses were significantly higher in the healthy control participants than in the patients with type 2 diabetes, both before and after insulin treatment (Table 1).

Glucagon

The average fasting plasma glucagon concentrations during the three experimental days were similar before insulin treatment (14 ± 3, 13 ± 1 and 14 ± 2 pmol/l) on the saline, GIP and GLP-1 days, respectively (not significant). Insulin treatment significantly lowered fasting plasma glucagon concentrations in all three groups (11 ± 2, 11 ± 2 and 8 ± 1 pmol/l on the saline, GIP and GLP-1 days, respectively, with no difference between the groups; Fig. 3). The corresponding values in the healthy control participants were similar on the three experimental days (10 ± 2, 9 ± 2 and 9 ± 2 pmol/l for saline, GIP and GLP-1 respectively; not significant) and, on the average, significantly lower than those of the patients before insulin treatment, but not after treatment (Fig. 3). In the patients with type 2 diabetes, plasma glucagon decreased slowly and similarly during all six clamps, reaching a stable nadir level after 65 min; the decreases (fasting minus nadir) were 7 ± 1 pmol/l before insulin treatment during saline infusion, 7 ± 0.2 pmol/l during GLP-1 infusion and 6 ± 0.5 pmol/l during GIP infusion (not significant); after insulin treatment, during saline infusion the decrease was 6 ± 0.4 pmol/l, during GLP-1 infusion it was 6 ± 0.5 pmol/l and during GIP infusion it was 6 ± 0.4 pmol/l (not significant). In the healthy control participants plasma glucagon decreased similarly during all three clamps to reach a stable nadir level after 25 min, the decrease (fasting minus nadir) being 6 ± 0.2 pmol/l on the saline day, 7 ± 0.1 pmol/l during GLP-1 infusion and 7 ± 0.3 pmol/l during GIP infusion (not significant). When comparing the decreases (fasting minus nadir) there were no significant differences before and after insulin treatment or between the patients and the healthy control participants. However, the patients with type 2 diabetes had a nadir level of 8 ± 1 pmol/l before insulin treatment and 4 ± 1 pmol/l after insulin treatment (p < 0.05) while the healthy control participants had a nadir level of 3 ± 1 pmol/l (p < 0.05 for patients with type 2 diabetes before insulin treatment vs healthy control participants). Nadir levels were not significantly different between healthy control participants and patients with type 2 diabetes after insulin treatment. Decremental areas over the curves (AOCs) for glucagon were similar in all groups, as shown in Table 2.

Plasma glucagon in patients with type 2 diabetes (a) and in healthy control participants (b) during GLP-1 infusions before (white squares) and after (black squares) insulin treatment, during GIP infusions before (white circles) and after (black circles) insulin treatment and during saline infusions before (white triangles) and after (black triangles) insulin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and during GLP-1 (black squares), GIP (black circles) and saline (black triangles) infusions in healthy control participants

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are: (1) the demonstration of the complete lack of effects on insulin and glucagon secretion of the major incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP, when these are infused into patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes at rates resulting in concentrations corresponding to those observed under physiological circumstances (whereas the same concentrations showed a significant effect in healthy controls); (2) the partial restoration of the effects of the hormones after 4 weeks of near-normalisation of plasma glucose concentration. The findings underscore the loss of insulinotropic effects of the incretin hormones as the major reason for the loss of the incretin effect observed in patients with type 2 diabetes, a loss that undoubtedly contributes importantly to the inappropriate insulin secretion that characterises these patients. The findings also suggest, in agreement with several earlier observations, that the loss of the insulinotropic effect may be secondary to the development of diabetes [29], perhaps as a result of glucotoxicity, but also raise the possibility that their effects may be restored with improved glycaemic control, thereby potentially generating a positive feed-forward cycle that may result in continuing improvement of metabolic control. Our results on the restoration of beta cell responsiveness to GIP after insulin treatment are in accordance with data obtained in Zucker rats as a model of diabetes, in which normalisation of hyperglycaemia returned beta cell GIP receptor mRNA levels to the normal level and restored beta cell sensitivity to GIP [30].

Inspection of the plasma concentrations of the incretin hormones obtained by the infusions (which, as expected [14, 15] were similar in patients and healthy controls) reveals that the profiles were strongly similar to those observed during the first hours after meal ingestion in healthy controls [31]. Both the postprandial and the present concentration profiles include gradual increases with time, for GLP-1 resulting in a plateau after 20 min and for GIP after 90 min, in agreement with the very rapid elimination of GLP-1 and somewhat slower elimination rates of GIP. The slow increase (compared with a primed infusion) probably explains why the infusion did not augment first-phase insulin secretion (0–10 min) in the healthy controls, as observed in other studies [32], and also did not result in any early stimulation of insulin secretion in the patients either before or after insulin therapy, as observed previously in protocols with higher rates of infusion [7, 33]. The fasting plasma insulin level did not differ significantly before and after insulin treatment, but tended to be slightly higher after insulin treatment, because of the contribution of exogenous insulin injected the evening before the studies. We cannot exclude some negative feedback effect on the beta cells of this slightly higher insulin level in the basal state, whereas studies have indicated that insulin even in higher concentrations fails to suppress glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [34, 35].

It is also in agreement with previous observations [36] that, when administered in physiological amounts in healthy controls, the insulinotropic effects of the two hormones are about equal and result in almost similar increases in glucose turnover, as indicated by similar increases in the rates of infusion of glucose needed to maintain the clamp. However, since the infusion rate of GIP was threefold higher and resulted in considerably higher plasma concentrations, GIP is clearly less potent then GLP-1.

The lack of effect of GIP on second-phase insulin secretion in the patients when in poor glycaemic control is in agreement with previous observations in which GIP, infused at rates as high as 16 pmol kg body weight−1 min−1, was incapable of increasing insulin secretion or glucose turnover [7]. A decreased potency of GLP-1 with regard to enhancing glucose-induced insulin secretion was observed in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with healthy controls by Kjems et al. [37], who studied beta cell sensitivity to glucose during infusion of GLP-1 at increasing rates. As for efficacy, GLP-1 has repeatedly, albeit in supraphysiological amounts and in contrast to GIP, been demonstrated to be strongly insulinotropic also in patients with type 2 diabetes. Therefore, its possible contribution to the loss of the incretin effect in type 2 diabetes has been unclear. However, the present finding of a complete lack of effect of physiological elevations of GLP-1 dramatically underscores that the incretin deficiency is due to deficiencies of both of the incretin hormones.

High infusion rates of GLP-1 have also been demonstrated to restore the ability of glucose to inhibit glucagon secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes, but also, regarding glucagon, there was no effect of the physiological amounts of GLP-1 infused in our patients, in whom the glucose-induced suppression of glucagon secretion was significantly delayed and resulted in higher levels than in the healthy controls. As expected [7, 38], neither GLP-1 nor GIP had any influence on the glucose-induced suppression of glucagon secretion in the healthy control participants, presumably because of the pronounced effect of glucose alone.

The mechanism behind the lost effect of the incretin hormones is not clear, but several observations [29] suggest that the loss of GIP action is secondary to the development of diabetes. Thus, this deficiency is seen in other types of diabetes, notably diabetes secondary to chronic pancreatitis, but also early type 1 diabetes, maturity-onset diabetes of the young and late autoimmune diabetes of the adult [8]. Conversely, the insulinotropic effects of GIP were preserved in women with a history of gestational diabetes and therefore at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes [39]. The deficiency would have been expected to be demonstrable in these women if it had been a primary event. In a previous investigation, a decreased insulinotropic action of GIP was found in about 50% of first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes, pointing towards an early, possibly genetic defect [40], but in subsequent investigations these individuals, who were not glucose-intolerant, turned out to have a normal incretin effect, so the finding probably reflected a general beta cell dysfunction in these relatives rather than a specific incretin defect [41]. Given that the loss of incretin action is likely to be secondary to the development of diabetes, it might be expected that improvement of metabolic control could result in at least a partial restoration of incretin action, and this is the hypothesis that we investigated in the present study. A beneficial effect of insulin treatment and strict glycaemic control of beta cell function has been documented in several studies [18, 20, 22–24, 42–44]. For instance, Turner and co-workers demonstrated in people with mild diabetes that 3 days of normoglycaemia enhanced the first-phase insulin responses to intravenous glucose [23], while Garvey and colleagues found that 3 weeks of continued subcutaneous insulin infusion in patients with type 2 diabetes and a long duration of diabetes improved insulin secretion in response to mixed meals and to intravenous glucagon administration, whereas the first-phase insulin response was unchanged [18]. Kosaka et al. [44] demonstrated that the insulin response to a meal in patients with type 2 diabetes improves with improved glucose control regardless of treatment (diet, sulfonylurea or insulin), suggesting that amelioration of hyperglycaemia improves beta cell function. Note that in the present study insulin treatment and near-normalisation of blood glucose did not improve beta cell responsiveness to glucose alone. This result is in agreement with our previous study, and indicates that the absence of responsiveness to intravenous glucose is a fundamental beta cell defect in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetes of several years’ duration [42].

The insulin treatment protocol observed in the present study resulted in greatly improved glycaemic profiles that approached normal levels, although completely normal fasting glucose values were not achieved. Since it is not known at what level of dysregulation the effects of the incretin hormones on islet function are lost and since we did not obtain complete normalisation of glycaemic profiles, it remains possible that further optimisation of glycaemic control could have even more pronounced effects.

In the present study we measured only total GLP-1 and GIP. In theory the DPP-IV activity may have changed and thereby the level of intact GLP-1 and GIP before and after insulin treatment may also have changed. We have demonstrated a higher DPP-IV activity in people with type 2 diabetes compared with glucose-tolerant participants [45]. In the participants with type 2 diabetes, a positive correlation between HbA1c and DPP-IV was demonstrated [45]. Nevertheless, in a previous study the intact GLP-1 level did not differ before and after near-normalisation of blood glucose using aggressive insulin treatment when the same amount of GLP-1 was infused intravenously [42]. In another study we have demonstrated similar elimination rates of GLP-1 and GIP in obese type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects [14, 15], indicating that higher intact GLP-1 and GIP levels after insulin treatment cannot explain the present results.

Thus, the loss of insulinotropic effects of the incretin hormones does seem to be secondary to the metabolic perturbation resulting from type 2 diabetes. This is of considerable clinical interest, since the loss of the incretin effect is likely to contribute importantly to the insufficient insulin secretion characterising type 2 diabetes. The partly restored incretin hormone actions after amelioration of hyperglycaemia may be particularly relevant for diabetes treatment based on inhibitors of the enzyme DPP-IV, which protect and therefore elevate the plasma levels and actions of the active incretin hormones. As metabolic control gradually improves, the actions of incretin hormones may be restored, explaining why the full effects of the DPP-IV inhibitors seem to develop rather slowly (after 3–4 months of therapy) [46], and may also explain why they are so clinically effective in spite of the rather moderate elevations of the incretin hormone levels that they bring about [47].

Although this study does not elucidate why acute administration of supraphysiological doses of GLP-1 is insulinotropic in patients with type 2 diabetes whereas GIP has lost its effects, it does show that the insulinotropic effect of GIP is not permanently lost in type 2 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- AOC:

-

area over the curve

- DPP-IV:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1:

-

glucagon-like peptide 1

References

Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC (2003) Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52:102–110

Porte D Jr (1991) Banting lecture 1990. Beta-cells in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 40:166–180

Turner R, Cull C, Holman R (1996) United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 17: a 9-year update of a randomized, controlled trial on the effect of improved metabolic control on complications in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 124:136–145

Creutzfeldt W, Nauck M (1992) Gut hormones and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Rev 8:149–177

Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W (1986) Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 29:46–52

Tronier B, Dejgaard A, Madsbad S (1985) Absence of incretin effect in obese type 2 and diminished effect in lean type 2 and obese subjects. Diab Res Clin Pract (Suppl 1):S568

Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2002) Defective amplification of the late phase insulin response to glucose by GIP in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia 45:1111–1119

Vilsboll T, Knop FK, Krarup T et al (2003) The pathophysiology of diabetes involves a defective amplification of the late-phase insulin response to glucose by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide regardless of etiology and phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:4897–4903

Toft-Nielsen MB, Damholt MB, Madsbad S et al (2001) Determinants of the impaired secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3717–3723

Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Deacon CF, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2001) Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon-like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 50:609–613

Dube PE, Brubaker PL (2004) Nutrient, neural and endocrine control of glucagon-like peptide secretion. Horm Metab Res 36:755–760

Holst JJ (2004) On the physiology of GIP and GLP-1. Horm Metab Res 36:747–754

Deacon CF, Johnsen AH, Holst JJ (1995) Degradation of glucagon-like peptide-1 by human plasma in vitro yields an N-terminally truncated peptide that is a major endogenous metabolite in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:952–957

Vilsboll T, Agerso H, Krarup T, Holst JJ (2003) Similar elimination rates of glucagon-like peptide-1 in obese type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:220–224

Vilsboll T, Agerso H, Lauritsen T et al (2006) The elimination rates of intact GIP as well as its primary metabolite, GIP 3-42, are similar in type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects. Regulatory Pept 137:168–172

Anonymous (1998) Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 352:837–853

Anonymous (1998) Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 352:854–865

Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, Hamman RF, Kolterman OG (1985) The effect of insulin treatment on insulin secretion and insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 34:222–234

Gutniak M, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ahren B, Efendic S (1992) Antidiabetogenic effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 (7-36) amide in normal subjects and patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 326:1316–1322

Hidaka H, Nagulesparan M, Klimes I et al (1982) Improvement of insulin secretion but not insulin resistance after short term control of plasma glucose in obese type II diabetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 54:217–222

Poitout V, Robertson RP (2002) Minireview: Secondary beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes—a convergence of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. Endocrinology 143:339–342

Schmeltz R, Wendorff HJ, Field JB (1978) Effect of control of blood glucose on plasma insulin responses to various stimuli in secondary failures to oral hypoglycemic agents and in newly diagnosed, maturity onset, ketosis-resistant diabetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 46:519–527

Turner RC, McCarthy ST, Holman RR, Harris E (1976) Beta-cell function improved by supplementing basal insulin secretion in mild diabetes. Br Med J 1:1252–1254

Vague P, Moulin JP (1982) The defective glucose sensitivity of the B cell in non insulin dependent diabetes. Improvement after twenty hours of normoglycaemia. Metabolism 31:139–142

Orskov C, Rabenhoj L, Wettergren A, Kofod H, Holst JJ (1994) Tissue and plasma concentrations of amidated and glycine-extended glucagon-like peptide I in humans. Diabetes 43:535–539

Krarup T, Holst JJ (1984) The heterogeneity of gastric inhibitory polypeptide in porcine and human gastrointestinal mucosa evaluated with five different antisera. Regulatory Pept 9:35–46

Krarup T, Madsbad S, Moody AJ et al (1983) Diminished immunoreactive gastric inhibitory polypeptide response to a meal in newly diagnosed type I (insulin-dependent) diabetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 56:1306–1312

Orskov C, Jeppesen J, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (1991) Proglucagon products in plasma of noninsulin-dependent diabetics and nondiabetic controls in the fasting state and after oral glucose and intravenous arginine. J Clin Invest 87:415–423

Knop FK, Vilsboll T, Hojberg PV et al (2007) The insulinotropic effect of GIP is impaired in patients with chronic pancreatitis and secondary diabetes mellitus as compared to patients with chronic pancreatitis and normal glucose tolerance. Regul Pept 144:123–130

Piteau S, Olver A, Kim SJ et al (2007) Reversal of islet GIP receptor down-regulation and resistance to GIP by reducing hyperglycemia in the Zucker rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 362:1007–1012

Orskov C, Wettergren A, Holst JJ (1996) Secretion of the incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide correlates with insulin secretion in normal man throughout the day. Scand J Gastroenterol 31:665–670

Fehse F, Trautmann M, Holst JJ et al (2005) Exenatide augments first- and second-phase insulin secretion in response to intravenous glucose in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5991–5997

Zander M, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, Holst JJ (2002) Effect of 6-week course of glucagon-like peptide 1 on glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes: a parallel-group study. Lancet 359:824–830

Bratusch-Marrain PR, Waldhausl WK (1985) Suppression of basal, but not of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by human insulin in healthy and obese hyperinsulinemic subjects. Metabolism 34:188–193

Murayama Y, Kawai K, Watanabe Y, Yoshikawa H, Yamashita K (1989) Insulin and glucagon secretion are suppressed equally during both hyper- and euglycemia by moderate hyperinsulinemia in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 68:925–931

Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2003) Both GLP-1 and GIP are insulinotropic at basal and postprandial glucose levels and contribute nearly equally to the incretin effect of a meal in healthy subjects. Regulatory Pept 114:115–121

Kjems LL, Holst JJ, Volund A, Madsbad S (2003) The influence of GLP-1 on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: effects on beta-cell sensitivity in type 2 and nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes 52:380–386

Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W (1993) Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7-36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 91:301–307

Meier JJ, Gallwitz B, Askenas M et al (2005) Secretion of incretin hormones and the insulinotropic effect of gastric inhibitory polypeptide in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Diabetologia 48:1872–1881

Meier JJ, Hucking K, Holst JJ, Deacon CF, Schmiegel WH, Nauck MA (2001) Reduced insulinotropic effect of gastric inhibitory polypeptide in first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 50:2497–2504

Nauck MA, El Ouaghlidi A, Gabrys B et al (2004) Secretion of incretin hormones (GIP and GLP-1) and incretin effect after oral glucose in first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept 122:209–217

Hojberg PV, Zander M, Vilsboll T et al (2008) Near normalisation of blood glucose improves the potentiating effect of GLP-1 on glucose-induced insulin secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 51:632–640

Hojberg PV, Vilsboll T, Zander M et al (2006) 4-weeks of near-normalisation of blood glucose has no effect on postprandial GLP-1 secretion but enhances beta cell responsivenes during a meal in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 49(Suppl. 1):403–404

Kosaka K, Kuzuya T, Akanuma Y, Hagura R (1980) Increase in insulin response after treatment of overt maturity-onset diabetes is independent of the mode of treatment. Diabetologia 18:23–28

Ryskjaer J, Deacon CF, Carr RD et al (2006) Plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-IV activity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus correlates positively with HbA1c levels, but is not acutely affected by food intake. Eur J Endocrinol 155:485–493

Ahren B, Gomis R, Standl E, Mills D, Schweizer A (2004) Twelve- and 52-week efficacy of the dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor LAF237 in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:2874–2880

Nauck MA, El-Ouaghlidi A (2005) The therapeutic actions of DPP-IV inhibition are not mediated by glucagon-like peptide-1. Diabetologia 48:608–611

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our volunteers, whose availability made this work possible, and to S. Reimer, L. Albeck and N. Kjeldsen for technical assistance. Special thanks are due to J. M. Højberg for helping with the insertion of difficult intravenous catheters.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Højberg, P.V., Vilsbøll, T., Rabøl, R. et al. Four weeks of near-normalisation of blood glucose improves the insulin response to glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 52, 199–207 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1195-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-008-1195-5