Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Type 1 diabetes is associated with premature arterial disease. Bone-marrow derived, circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are believed to contribute to endothelial repair. The hypothesis tested was that circulating EPCs are reduced in young people with type 1 diabetes without vascular injury and that this is associated with impaired endothelial function and increased carotid intima–media thickness (CIMT).

Methods

We compared 74 people with type 1 diabetes with 80 healthy controls. CD34, CD133, vascular endothelial (VE) growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) and VE-cadherin antibodies were used to quantify EPCs and progenitor cell subtypes using flow-cytometry. Ultrasound assessment of endothelial function by brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) and CIMT was made. Circulating endothelial markers, inflammatory markers and plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) levels were measured.

Results

CD34+VE-cadherin+, CD133+VE-cadherin+ and CD133+VEGFR-2+ EPC counts were significantly lower in people with diabetes (46–69%; p = 0.004–0.043). In people with type 1 diabetes, FMD was reduced by 45% (p < 0.001) and CIMT increased by 25% (p < 0.001), these being correlated (r = −0.25, p = 0.033). There was a significant relationship between FMD and CD34+VE-cadherin+ (r = 0.39, p = 0.001), CD133+VEGFR-2+ (r = 0.25, p = 0.037) and CD34+ (r = 0.34, p = 0.003) counts. Circulating high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, PAI-1, interleukin-6 and E-selectin were significantly higher in the diabetes group (p < 0.001 to p = 0.049), the last two of these correlating with FMD (r = −0.27, p = 0.028 and r = −0.24, p = 0.048, respectively).

Conclusions/interpretation

These findings suggest that abnormalities of endothelial function in addition to pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic states are already common in people with type 1 diabetes before development of clinically evident arterial damage. Low EPC counts confirm risk of macrovascular complications and may account for impaired endothelial function and predict future cardiovascular events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus leads to long-term vascular damage to small vessels (microvascular) and major arteries (macrovascular), and to impaired vascular repair. Type 1 diabetes confers a two- to tenfold increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease compared with the background population [1, 2]. Diabetes is associated with endothelial dysfunction and reduced neovascularisation in response to tissue ischaemia [3, 4]. It has been suggested that contributory factors to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis include postprandial glucose levels and arterial wall inflammation [5, 6]. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are bone-marrow derived cells that were first described in 1997 [7]. It has been hypothesised that EPCs play a role in re-endothelialisation of blood vessels damaged by ischaemia [7–10]. EPCs potentially contribute to endothelial repair by homing into sites of endothelial injury at sites of ischaemia and damage, and thus maintain the integrity of the endothelial milieu.

EPCs are a heterogeneous population characterised by the expression of surface markers of endothelial (vascular endothelial [VE]-cadherin [also known as CD144], vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 [VEGFR-2], CD31 and von Willebrand factor) and haemopoietic progenitor (CD34, CD133) lineages [7, 11–16]. Circulating EPCs consist of cells at various stages of maturation. The CD133+VEGFR-2+ cells are believed to be less mature or early circulating EPCs [17], while more mature circulating EPCs, which have lost CD133, are positive for CD34+VEGFR-2+ and CD34+VE-cadherin+ [18].

Mature and immature EPCs contribute to a similar extent to neovasculogenesis in vivo [19]. VEGFR-2 mediates most of the downstream angiogenic effects of VEGF, including microvascular permeability and endothelial cell proliferation, while VE-cadherin is specifically expressed in adherent junctions of endothelial cells and exerts important functions in cell–cell adhesion, thus promoting the integrity of the endothelium [20, 21].

Some cardiovascular risk factors have been found to be associated with decreased circulating EPCs [22, 23]. Furthermore, Werner and colleagues reported both a step-wise increase in cumulative event-free survival of life-threatening cardiovascular incidents with increasing baseline levels of CD34+VEGFR-2+ EPCs, and an association between CD133+ cell counts and reduced occurrence of a first major cardiovascular event and hospitalisation [24]. Circulating EPCs in people with diabetes are not only reduced in number, but also have impaired function [25–28].

Flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) is an established non-invasive means of assessing endothelial function by measuring vasodilatation in the brachial artery in response to shear stress associated with increased blood flow [29]. The FMD of peripheral arteries has been shown to reflect that of the coronary circulation [30, 31]. Endothelial dysfunction is believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and can be detected years before overt coronary artery disease becomes manifest [29, 32]. Endothelial dysfunction has consistently been reported in type 2 diabetes [33], in contrast to type 1 diabetes, where only half of the studies have reported it [33]. It has been suggested that dysfunction in endothelial-dependent and -independent vasodilatation is a continuum, with people with good glycaemic control and normal albumin excretion at one end, and those with microalbuminuria, poor glycaemic control and long duration of diabetes at the other [33–35]. It is not known whether differences in the number of circulating EPCs could explain the gradient in endothelial dysfunction in people with type 1 diabetes. Accordingly, we investigated whether the reduction in the number of circulating EPCs in young people with type 1 diabetes without clinically evident macrovascular disease or even occult damage as marked by the presence of microalbuminuria is associated with impaired endothelial function as assessed by FMD and with carotid intima–media thickness (CIMT). Secondary objectives were to determine the relationship between circulating EPCs and more conventional circulating endothelial markers. The hypothesis to be tested was that: (1) the number of circulating EPCs is reduced in young people with type 1 diabetes without microalbuminuria or known macrovascular disease; and (2) this is associated both with impaired endothelial function assessed by FMD, and with CIMT.

Methods

Participants

People with type 1 diabetes without macrovascular disease or microalbuminuria were compared with healthy volunteers, all aged 16 to 35 years. For inclusion, people with type 1 diabetes required serum C-peptide <0.15 nmol/l when plasma glucose was >5.5 mmol/l or a history of ketoacidosis with type 1 diabetes phenotype. All people with diabetes were insulin-treated and had a duration of diabetes of >1 year. Absence of microalbuminuria was determined by measuring urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (last three samples all <2.5 mg/mmol in men, <3.5 mg/mmol in women). Macrovascular disease was ruled out on the basis of: no history of a cardiovascular event or procedure, no angina (Rose questionnaire), no ischaemic ECG abnormalities, no use of statins or ACE inhibitors, and no abnormal pedal pulses. The participants were attending the Newcastle Diabetes Centre for routine diabetes care. The age-matched non-diabetic controls were recruited through contacts of the participants and investigators, and screened to exclude the possibility of arterial disease. After local Ethics Committee approval, all participants gave informed written consent to participation in the study.

The people with diabetes were on the following insulin regimens: meal-time + basal insulin analogue (n = 60); meal-time + basal human insulin (n = 2); premixed analogues (n = 4); premixed human insulin (n = 7); continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (n = 1). Retinopathy was present in 46 (62%) of the people with diabetes, and typically of many clinical populations [36], average glucose control was moderately poor.

Procedures

Study procedures were performed at Newcastle Diabetes Centre and Department of Medical Physics. Medical examination included a 12-lead ECG, the Rose angina questionnaire, blood pressure measurement (seated) using automatic sphygmomanometer (HEM-773AC; Omron, Bannockburn, IL, USA) and measurement of body weight in indoor clothing without shoes.

Women were studied in the first 10 days of the menstrual cycle. All the participants attended early morning, fasting, having avoided caffeinated beverages, cigarettes and strenuous exercise since the previous evening. They were given a low-fat breakfast informally matched to usual carbohydrate intake, together with usual insulin dose in those with diabetes. A 2 h postprandial blood sample was taken and the ultrasound procedures performed. The postprandial state was chosen to avoid the insulin-deficient state often found in people with type 1 diabetes at the end of the night, and because of evidence that the postprandial state is more pathogenetically significant for the development of vascular damage in people with diabetes [5].

Measurements and assays

Endothelial progenitor cells

EPCs were quantified by the surface markers CD34, CD133, VEGFR-2 and VE-cadherin in the mononuclear cell fraction that included the cells in the lymphocyte gate and the CD14-positive monocyte gate on flow-cytometry. EPCs were identified as cells expressing both a progenitor (CD34 or CD133) and an endothelial (VEGFR-2 or VE-cadherin) marker, which thus included CD34+VE-cadherin+, CD34+VEGFR-2+, CD133+VEGFR-2+ and CD133+VE-cadherin+ cells. Circulating progenitor cell subtypes were identified as cells expressing CD34 or CD133.

Whole blood (100 µl EDTA sample) with PBS 100 µl was incubated for 30 min with the following monoclonal antibodies: PE-Cy7 conjugated anti-human CD14 (557742; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA); PerCP-Cy 5.5-conjugated anti-CD34 (347222; BD Pharmingen); APC-conjugated anti-CD133 (293C3 clone; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany); PE-conjugated anti-VEGFR-2 (FAB357P; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA); and FITC-conjugated polyclonal antibody to VE-cadherin (CD144) (ALX-210-232-F; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA). Matching isotype control antibodies with identical fluorescent tag were employed as an internal control for each individual to enable setting of the count threshold and exclusion of background noise. Following incubation, erythrocytes were lysed with 750 µl diluted Pharmlyse (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and the samples were assessed by flow-cytometry on an LSR-II (BD Biosciences) machine. A mean of 340,000 total events was captured (310,000 events for the controls).

Flow-mediated dilatation

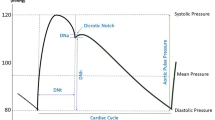

Brachial artery FMD was measured by a single trained scientist (L. Sibal) with high-resolution ultrasonography using a 5–12 MHz linear transducer on an HDI 5000 system (Advanced Technology Laboratories, Bothell, Washington, USA) with data acquisition by artificial neural network software (VIA Software, London, UK) imaging the vessel wall 20 times/s and in accordance with international guidelines [37, 38]. The brachial artery was studied 20 to 100 mm proximal to the antecubital fossa in supine participants after 15 min rest. Pressure in an upper-forearm sphygmomanometer cuff was raised to 250 mmHg for 5 min and FMD automatically calculated as the percentage increase in mean diastolic diameter after reactive hyperaemia 55 to 65 seconds after deflation to baseline. After a further 15 min, 400 µg sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) was given and diastolic diameter remeasured after 5 min for measurement of endothelial-independent dilatation. The coefficient of variation for FMD was 8.7% with a mean (SD) day-to-day absolute difference of 0.48 (0.38)% in ten controls.

Carotid intima–media thickness

CIMT was measured by a single trained scientist (L. Sibal) at the far wall of the right and left common carotid artery 10 to 20 mm proximal to the carotid bulb using high-resolution ultrasonography (HDI 5000; Advanced Technology Laboratories). Images were stored digitally and offline measurements of the distance between the lumen interface and the media–adventitia interface made with a frame grabber and bitmap software. The mean CIMT was calculated from ten measurements on each artery. The coefficient of variation was 3.2% with a mean day-to-day absolute difference of 0.0146 (0.0159) mm in ten controls.

Biochemical analysis

HbA1c was measured using an HPLC (Tosoh Bioscience, Stuttgart, Germany) method (normal <6.1%). Serum lipids were measured by standard enzymatic methods. Other biochemical analyses were by standard methods in the same clinical trials-accredited laboratory (Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle, UK). Assay methods, all on postprandial samples, were: plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) by ELISA; TNF-α and IL-6 by a sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique; and soluble E-selectin, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and soluble vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 by solid-phase ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Results are given as mean ± SE, median (interquartile range [IQR]) or number (%). Statistical comparison was by Student’s unpaired t test, the Mann–Whitney test or the χ 2 test. Correction for multiple testing was not made, as the multiple measurements, particularly within the group of progenitor cells, were not expected to be independent. Pearson’s correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rho was calculated to assess relationships of measures. Multivariate regression analysis was used to determine independent predictors of FMD and CIMT, performed where the univariate p value was <0.100.

No formal statistical power calculation was possible for this study; post-hoc calculations show that the study has a power of >99% to detect an FMD difference of 3.0% between the two groups (95% power to detect a difference of 2.0% in FMD) and is similarly overpowered to detect a 20% difference in CIMT between the two groups. An initial estimate of n = 80 in each group was chosen because it was anticipated that only a proportion of people with diabetes might have abnormalities and that some EPC counts could be close to the limits of detection when reduced in people with diabetes.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The type 1 diabetes and control groups were of similar young age and age distribution, and of similar non-obese BMI (Table 1). Accordingly there were no differences in measures associated with obesity or the metabolic syndrome such as waist circumference, systolic blood pressure or serum lipid profile. Differences were restricted to blood glucose control, which was moderately poor, as reflected in HbA1c and both fasting and postprandial plasma glucose levels.

Endothelial progenitor cells and progenitor cell subtypes

The cell counts for EPCs with CD34+VE-cadherin+, CD133+VEGFR-2+ and CD133+VE-cadherin+ were statistically significantly lower (reductions of 46–69%) in the people with type 1 diabetes compared with the healthy controls (p = 0.004 to 0.043) (Table 2). The progenitor cell subtypes with CD34+ and CD133+ cell counts were also significantly lower (reductions of 38–50%, p = 0.005 to 0.041). The cell count for CD34+VEGFR-2+ was numerically lower (29%) but not statistically significantly different (Table 2).

There were significant relationships between counts of different EPCs and between EPCs and progenitor cell subtypes (Table 3).

Flow-mediated dilatation

Endothelial function measured as FMD was significantly reduced by 45% in the people with type 1 diabetes (4.95 ± 0.34% vs controls 9.03 ± 0.38%; p < 0.001), as was GTN-induced (endothelium-independent) vasodilatation (by 28%; 16.7 ± 0.7 vs 23.4 ± 0.8%) (Table 2). The baseline diameter of the brachial artery in people with diabetes and healthy controls was similar (3.41 ± 0.06 vs 3.44 ± 0.06 mm). FMD remained significantly lower in the people with diabetes compared with healthy controls after correcting for GTN-induced vasodilatation (FMD:GTN ratio 0.34 ± 0.03 vs 0.42 ± 0.02, p = 0.025). There was no correlation between FMD and plasma glucose or HbA1c (Table 4).

Carotid intima–media thickness

People with type 1 diabetes had 24% greater CIMT than healthy people (p < 0.001) (Table 2). In the group with diabetes, CIMT correlated with age (r = 0.56, p < 0.001) and negatively with FMD (r = −0.25, p = 0.033) (Fig. 1, Table 4). There was no correlation between CIMT and plasma glucose or HbA1c (r = −0.06, p = 0.642 and r = −0.05, p = 0.690).

Circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction

There were significantly higher levels of circulating high-sensitivity (hs) C-reactive protein (CRP) (p = 0.049), PAI-1 (p = 0.007), IL-6 (p < 0.001) and E-selectin (p = 0.013) in the people with type 1 diabetes than in healthy controls, but TNF-α and other adhesion molecules did not differ (Table 2).

Other relationships between measures

Correlation within the diabetes group was found between FMD and cell counts for EPC CD34+VE-cadherin+ (r = 0.39, p = 0.001), CD133+VEGFR-2+ (r = 0.25, p = 0.037) and circulating progenitor cell subtype CD34+ (r = 0.34, p = 0.003) (Table 4). On multivariate regression analysis adjusting for age and sex, the relationship for CD34+ and CD34+VE-cadherin+ with FMD remained (Table 4). This was not changed by adding duration of diabetes (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively).

In addition to adjusting for HbA1c, the multivariate linear regression model analyses used to test for independent predictors of FMD included the factors reaching p < 0.100 on univariate analysis, i.e.: weight, systolic BP and E-selectin in all models, together with one of the circulating inflammatory markers (hsCRP or IL-6 or TNF-α) and one of the progenitor cell counts (CD34+VE-cadherin+ or CD133+VEGFR-2+ or CD34+ cells). CD34+VE-cadherin+ and CD34+ cells were then the only predictors of FMD in people with diabetes (model with CD34+VE-cadherin+ cells β = 0.43, p < 0.001, r 2 = 0.28 for the whole model; model with CD34+ cells β = 0.38, p = 0.003, r 2 = 0.24 for the whole model).

Comparisons of the people with type 1 diabetes in the lowest quarter of FMD (<2.72%) with those in the highest three quarters (≥2.72%) revealed no differences in anthropometric measures or conventional cardiovascular risk factors (Electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). However, the CD133+VEGFR-2+ count was lower (median 1 [IQR 0–18] vs 8 [IQR 1–41], p = 0.035) and CIMT higher (0.653 ± 0.020 vs 0.607 ± 0.010 mm, p = 0.027) in the lowest quarter. Cell counts for CD34+ (median 167 [IQR 100–331] vs median 289 [IQR 87–766], p = 0.352) and CD34+CD133+ (median 90 [IQR 30–141] vs median 155 [IQR 59–559], p = 0.739) were numerically much lower in the same quarter, but variance was high and the findings were not statistically significant.

CIMT and the EPC cell counts were not correlated in the diabetes group (data not shown).

We analysed (post hoc) our data in terms of HbA1c above or below 7.0%. FMD was significantly lower, the CIMT was significantly higher and CD133+VE-cadherin+ counts were lower in both groups with diabetes compared with healthy controls, but did not differ between the two groups. Furthermore, CD34+VE-cadherin+, CD34+ and CD133+ counts were lower in people with type 1 diabetes with HbA1c above 7.0% than in healthy controls, but did not differ between the diabetes subgroups.

In the type 1 diabetes group, there were significant negative univariate correlations between IL-6 and FMD (r = −0.27, p = 0.028), and between E-selectin and FMD (r = −0.24, p = 0.048) (Table 4), neither of which remained after adjustment for age and sex. There was also a significant inverse relationship between TNF-α and both CD133+ cell count (r = −0.41, p = 0.000) and CD34+CD133+ cell count (r = −0.25, p = 0.039).

Discussion

This study shows that young people with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes have impaired endothelial function, increased CIMT and reduced EPC counts. It also confirms increased levels of inflammatory (hsCRP, IL-6) and pro-thrombotic (PAI-1) markers in this population. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report a plausible association between EPC counts and both endothelial function and the interaction between various surrogate markers of increased cardiovascular risk in people with type 1 diabetes.

While diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, this is not limited to the more complex metabolic disorder of type 2 diabetes, people with type 1 diabetes having even greater age-standardised cardiovascular mortality rates, partly because of their younger age of impact of vascular disease. Aetiologically type 1 diabetes is a pure hormone deficiency disease and as such provides a better basis for studying the impact of hyperglycaemia (or insulin deficiency) alone on mechanisms of vascular injury in states uncomplicated, at least before nephropathy develops, by abnormalities of lipid profile and blood pressure. In the current study we chose to study young adults with type 1 diabetes, so the population is very similar in characteristics to the control non-diabetic group, except for measures of hyperglycaemia. Exclusion of those with extant cardiovascular disease or diabetic nephropathy was designed to avoid participants in whom vascular injury was already advanced and in whom endothelial repair mechanisms might therefore have been activated by arterial wall damage in the form of atherosclerotic plaque [39–41]. Nevertheless it is impossible to be sure that some individuals in our type 1 diabetic population did not have more significant disease (indeed in both populations). Further interventional studies are required for a true assessment of the effects of hyperglycaemia/hypoinsulinaemia on features related to endothelial dysfunction, which could only be made by studying people before and after normalisation of blood glucose levels.

Here we studied circulating EPCs expressing an endothelial marker (VEGFR-2/VE-cadherin) and a haemopoietic stem cell or bone-marrow-derived marker (CD34/CD133), and also circulating progenitor cell subtypes expressing haemopoietic stem cell markers alone (CD34/CD133) [7, 11–15, 17]. We found significant reductions in circulating cell counts of some populations of both classes of cells (endothelial progenitor, circulating progenitor cell subtypes) in young people with type 1 diabetes without any macrovascular disease or microalbuminuria. One problem with the study, which determined the relatively large number of people studied, is the small number of counts in some circulating cell populations, notably in the diabetes group where they were universally numerically reduced, such that statistical significance is strongest in general for the higher cell counts and absent for some of the smaller cell populations. Nevertheless statistical significance was found for both mature and immature EPC populations, notably CD34+VE-cadherin+, CD133+VEGFR-2+ and CD133+VE-cadherin+ cells. Some caution is needed in interpreting the findings beyond the primary hypothesis, as a series of measures is reported; however, the consistent relationships found between the different EPCs, and between the EPC counts and the progenitor subtype counts support the view that the secondary findings are reasonably secure.

These findings extend those of Loomans and colleagues, who used a semi-quantitative technique involving 4 to 7 days culture in vitro with detection of morphology, CD31+ and acetylated LDL uptake, and Ulex Europaeus agglutinin-1 binding in order to find a reduction in EPC number in people with type 1 diabetes [25]. People with impaired glucose tolerance have been reported to have decreased CD34+ progenitor cell subtypes, but not reduced CD34+VEGFR-2+ (EPC) cells, and post-glucose challenge glucose levels independently related to both CD34+ and CD34+VEGFR-2+ levels [42], but in this group metabolic abnormalities would be more extensive and not restricted to hyperglycaemia.

Here we extend the findings of altered EPC count by assessment in relation to functional measures of endothelial dysfunction and to circulating endothelial markers. Measurement of FMD in brachial artery is an accepted method for measuring endothelial function in the peripheral circulation [29, 30]. The technique has been used previously in children with diabetes and generated very similar data to our own in young adults [43]. Indeed in that study, ultrasound assessment was also made of CIMT in type 1 diabetic children, again with results remarkably similar to those of the current study. However those authors did not assess relationships to EPCs or circulating endothelial markers.

Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation determined by FMD measurement was positively correlated to CD34+ and CD34+VE-cadherin+ cell counts, a correlation which persisted after multivariate regression analysis, whereas a rather weaker correlation with CD133+VEGFR-2+ cell counts did not survive adjustment for age and sex. No association was found between CD34+VEGFR-2+ cells and FMD. However, this is possibly explained by the low number of CD34+ cells co-expressing VEGFR-2 in both groups studied. Deschaseaux and colleagues suggest that the phenotype CD34+VE-cadherin+ is a more specific marker than CD34+VEGFR-2+ for detection of late or mature circulating EPCs in blood [44].

Taken together, these associations are consistent with the possibility that abnormalities in EPC cell counts or function may be an early determinant of endothelial injury and consequent on the primary abnormality of type 1 diabetes (insulin deficiency and hyperglycaemia). In an animal model of hindlimb ischaemia–reperfusion injury, insulin treatment was found to improve the mobilisation of EPCs from bone marrow [45].

Accordingly, further study of EPCs, both as markers for risk of developing later cardiovascular disease and in the early pathogenesis of vascular damage, is indicated. We did not, however, find any relationship between CIMT and EPCs in the type 1 diabetes group, and indeed the relationship between FMD and CIMT was not in itself strong. This may be partly because CIMT measurements only detect small differences (around 0.1 mm) between the young people with diabetes and healthy participants, and also because both measurements (CIMT and EPCs) are close to the limits of their resolution. A previous study in middle-aged people did find a significant correlation between EPC number and CIMT [46]. Alternatively, however, FMD and CIMT may be looking at different parts of the same pathway of arterial wall damage, the former perhaps abnormalities of function and the latter early structural change.

Markers of inflammation such as CRP and IL-6 are increased in people at risk of cardiovascular disease [47]. Goldschmidt-Clermont and colleagues proposed that an inflammatory process that injures the arterial wall of people exposed to other risk factors could be linked to a deficient repair process of the arterial wall [48]. Previous studies have suggested that inflammatory markers are increased in people with type 1 diabetes, in whom the risk factor will be exposure to toxic glucose concentrations [49, 50]. Here those observations have been extended by finding increased levels of hsCRP, IL-6, PAI-1 (a pro-thrombotic marker) and E-selectin in young people with type 1 diabetes without evidence of arterial disease, together with some evidence of a relationship to FMD. In addition, negative correlations were found between CD133+ cell number and TNF-α, and FMD and IL-6. Relationships like these cannot determine causality, and it remains to be determined whether impaired vascular repair secondary to EPC abnormalities might be primary, or whether vascular inflammation in some way interferes with EPC count, or indeed whether positive feedback of abnormalities between these two groups of measures occurs.

The present work could be usefully extended by studies of functional abnormalities of EPCs in people with hyperglycaemia. Other areas of interest would be the question of whether pharmacological interventions that modify EPCs (count or function) improve endothelial function in people with type 1 diabetes.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that abnormalities of endothelial function are already common in young adults with type 1 diabetes before development of clinically evident arterial damage and that these abnormalities are associated with an increase in CIMT. The finding of low EPC counts and their relationship to abnormal FMD and circulating markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction suggests that abnormalities of endothelial repair mechanisms could have an important role in the initiation or exacerbation of early vascular injury. Also worthy of further attention is the use of decreased EPC number as a potential novel approach to identifying those people with type 1 diabetes who are at risk of cardiovascular disease in middle age.

Abbreviations

- CIMT:

-

Carotid intima–media thickness

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- EPCs:

-

Endothelial progenitor cells

- FMD:

-

Flow-mediated dilatation

- GTN:

-

Glyceryl trinitrate

- hs:

-

High-sensitivity

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- PAI-1:

-

Plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- VE:

-

Vascular endothelial

- VEGFR-2:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2

References

Dorman JS, Laporte RE, Kuller LH et al (1984) The Pittsburgh insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) morbidity and mortality study. Mortality results. Diabetes 33:271–276

Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, Bothat JL (1999) The British Diabetic Association Cohort Study 2: cause-specific mortality in patients with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 16:466–471

Sheetz MJ, King GL (2002) Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia’s adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA 288:2579–2588

Waltenberger J (2001) Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc Res 49:554–560

Ceriello A (2005) Postprandial hyperglycemia and diabetes complications: is it time to treat? Diabetes 54:1–7

Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. New Engl J Med 340:115–126

Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A et al (1997) Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 275:964–967

Kalka C, Masuda H, Takahashi T et al (2000) Transplantation of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 97:3422–3427

Kawamoto A, Gwon HC, Iwaguro H et al (2001) Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation 103:634–637

Rafii S, Lyden D (2003) Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nature Med 9:702–712

Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H et al (1999) Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nature Med 5:434–438

Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ et al (2001) Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nature Med 7:430–436

Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T et al (1999) Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res 85:221–228

Yamashita J, Itoh H, Hirashima M et al (2000) Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature 408:92–96

Rehman J, Parvathaneni L, Karlsson G et al (2004) Exercise acutely increases circulating endothelial progenitor cells and monocyte-/macrophage-derived angiogenic cells. J Am Coll Cardiol 43:2314–2318

Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D et al (2000) Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood 95:952–958

Urbich C, Dimmeler S (2004) Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res 95:343–353

Hristov M, Erl W, Weber PC (2003) Endothelial progenitor cells: mobilization, differentiation, and homing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23:1185–1189

Hur J, Yoon CH, Kim HS et al (2004) Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:288–293

Hicklin DJ, Ellis LM (2005) Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol 23:1011–1027

Lampugnani MG, Resnati M, Raiteri M et al (1992) A novel endothelial-specific membrane protein is a marker of cell-cell contacts. J Cell Biol 118:1511–1522

Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP et al (2003) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. New Engl J Med 348:593–600

Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A et al (2001) Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res 89:E1–E7

Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T et al (2005) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. New Engl J Med 353:999–1007

Loomans CJ, de Koning EJ, Staal FJ et al (2004) Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of vascular complications of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 53:195–199

Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM et al (2002) Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation 106:2781–2786

Fadini GP, Miorin M, Facco M et al (2005) Circulating endothelial progenitor cells are reduced in peripheral vascular complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 45:1449–1457

Caballero S, Sengupta N, Afzal A et al (2007) Ischemic vascular damage can be repaired by healthy, but not diabetic, endothelial progenitor cells. Diabetes 56:960–967

Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM et al (1992) Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 340:1111–1115

Neunteufl T, Katzenschlager R, Hassan A et al (1997) Systemic endothelial dysfunction is related to the extent and severity of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 129:111–118

Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD et al (1995) Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol 26:1235–1241

Healy B (1990) Endothelial cell dysfunction: an emerging endocrinopathy linked to coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 16:357–358

Yki-Jarvinen H (2003) Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction. Best Pract Res 17:411–430

Zenere BM, Arcaro G, Saggiani F, Rossi L, Muggeo M, Lechi A (1995) Noninvasive detection of functional alterations of the arterial wall in IDDM patients with and without microalbuminuria. Diabetes Care 18:975–982

Lambert J, Aarsen M, Donker AJ, Stehouwer CD (1996) Endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilation of large arteries in normoalbuminuric insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 16:705–711

Jensen T, Musaeus L, Molsing B, Lyholm B, Mandrup-Poulsen T (2002) Process measures and outcome research as tools for future improvement of diabetes treatment quality. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 56:207–211

Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ et al (2002) Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 39:257–265

Sidhu JS, Newey VR, Nassiri DK, Kaski JC (2002) A rapid and reproducible on line automated technique to determine endothelial function. Heart 88:289–292

Deckert T, Yokoyama H, Mathiesen E et al (1996) Cohort study of predictive value of urinary albumin excretion for atherosclerotic vascular disease in patients with insulin dependent diabetes. BMJ 312:871–874

Rossing P, Hougaard P, Borch-Johnsen K, Parving HH (1996) Predictors of mortality in insulin dependent diabetes: 10 year observational follow up study. BMJ 313:779–784

Sibal L, Law HN, Gebbie J, Dashora UK, Agarwal SC, Home P (2006) Predicting the development of macrovascular disease in people with type 1 diabetes: a 9-year follow-up study. Ann NY Acad Sci 1084:191–207

Fadini GP, Pucci L, Vanacore R et al (2007) Glucose tolerance is negatively associated with circulating progenitor cell levels. Diabetologia 50:2156–2163

Jarvisalo MJ, Raitakari M, Toikka JO et al (2004) Endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial intima–media thickness in children with type 1 diabetes. Circulation 109:1750–1755

Deschaseaux F, Selmani Z, Falcoz PE et al (2007) Two types of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients receiving long term therapy by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Eur J Pharmacol 562:111–118

Fadini GP, Sartore S, Schiavon M et al (2006) Diabetes impairs progenitor cell mobilisation after hindlimb ischaemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Diabetologia 49:3075–3084

Fadini GP, Coracina A, Baesso I et al (2006) Peripheral blood CD34+KDR+ endothelial progenitor cells are determinants of subclinical atherosclerosis in a middle-aged general population. Stroke 37:2277–2282

Ridker PM (2003) Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation 107:363–369

Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ (2003) Loss of bone marrow-derived vascular progenitor cells leads to inflammation and atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 146:S5–S12

Gomes MB, Piccirillo LJ, Nogueira VG, Matos HJ (2003) Acute-phase proteins among patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 29:405–411

Targher G, Bertolini L, Zoppini G, Zenari L, Falezza G (2005) Increased plasma markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction and their association with microvascular complications in type 1 diabetic patients without clinically manifest macroangiopathy. Diabet Med 22:999–1004

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Shenton and I. Harvey for advice on flow-cytometry, RDG Neely for biochemical analyses and A. Jones for nursing assistance. We are grateful for the generous donation of time and inconvenience by the people studied. The study was funded internally by Newcastle University.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Table 1

Comparison of type 1 diabetic patients with FMD below and above the 25th percentile (PDF 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sibal, L., Aldibbiat, A., Agarwal, S.C. et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, endothelial function, carotid intima–media thickness and circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction in people with type 1 diabetes without macrovascular disease or microalbuminuria. Diabetologia 52, 1464–1473 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1401-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1401-0