Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Increased arterial stiffness is a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events in adults with obesity-related insulin resistance (IR) or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adolescents with type 2 diabetes have stiffer vessels. Whether stiffness is increased in obesity/IR in youth is not known. We sought to determine if IR was a determinant of arterial stiffness in youth, independent of obesity and cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods

We measured cardiovascular risk factors, IR, adipocytokines and arterial stiffness (brachial artery distensibility [BrachD], pulse wave velocity [PWV]) and wave reflection (augmentation index [AIx]) in 343 adolescents and young adults without type 2 diabetes (15–28 years old, 47% male, 48% non-white). Individuals <85th percentile of BMI were classified as lean (n = 232). Obese individuals were grouped by HOMA index as not insulin resistant (n = 46) or insulin resistant (n = 65) by the 90th percentile for HOMA for lean. Mean differences were evaluated by ANOVA. Multivariate models evaluated whether HOMA was an independent determinant of arterial stiffness.

Results

Risk factors deteriorated from lean to obese to obese/insulin resistant (all p ≤ 0.017). Higher AIx, lower BrachD and higher PWV indicated increased arterial stiffness in obese and obese/insulin-resistant participants. HOMA was not an independent determinant. Age, sex, BMI and BP were the most consistent determinants, with HDL-cholesterol playing a role for BrachD and leptin for PWV (AIx R 2 = 0.34; BrachD R 2 = 0.37; PWV R 2 = 0.40; all p ≤ 0.02).

Conclusions/interpretation

Although IR is associated with increased arterial stiffness, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, especially obesity and BP, are the major determinants of arterial stiffness in healthy young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cardiovascular (CV) diseases are the leading cause of death throughout the world [1]. Increased arterial stiffness is an early marker for CV disease risk as stiffer vessels predict heart attack and stroke in adults, especially those with type 2 diabetes mellitus [2]. Non-diabetic adults with obesity-related insulin resistance (IR) also have increased stiffness that is associated with adverse events [3]. There are limited data suggesting that increased arterial stiffness may be seen in adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus [4]. However, whether uncomplicated obesity or obesity with IR is associated with higher levels of arterial stiffness in adolescents is not known. Therefore, we sought to examine the relationships between adiposity with and without IR and non-invasive measures of arterial stiffness in a group of non-diabetic, otherwise healthy, adolescents and young adults. We hypothesised that we would see a graded decline in arterial stiffness with greater levels of metabolic perturbation.

Methods

Study population

The study population consisted of 343 adolescents and young adults (age 15–28 years, 47% male, 48% non-white). Individuals were eligible if they were participating in a large longitudinal school-based study of the effect of obesity on development of diabetes [5]. Pregnant females and individuals with chronic disease or taking medication known to affect carbohydrate metabolism were excluded. Investigational review board approval was obtained and written informed consent was obtained from individuals aged ≥18 years or the guardians for individuals aged <18 years. Written assent was obtained for individuals aged <18 years.

Data collection

Anthropometrics

The average of two measures of height (portable stadiometer, RoadRod, Quick Medical, North Bend, WA, USA, or Accustat, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA) and weight (digital scale, SECA 770, SECA, Hanover, MD, USA) were used in the analyses. Individuals were classified as obese if their BMI was ≥85th percentile for US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) growth charts or ≥30 kg/m2 at any age.

Laboratory techniques

Venepuncture was performed after a minimum 10 h fast. Plasma glucose was measured using a Hitachi model 704 glucose analyser with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 1.2% and 1.6%, respectively. Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay using an anti-insulin serum raised in guinea pigs, 125I-labelled insulin (Linco, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a double antibody method to separate bound from free tracer with a sensitivity of 2 pmol and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 5% and 8%, respectively. All participants with a fasting plasma glucose ≥5.5 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) or 2 h post glucose load plasma glucose concentration ≥7.8 mmol/l (140 mg/dl) were excluded. HOMA was calculated according to the method of Sinha et al. [6] using insulin in micro-units per millilitre and glucose in millimoles per litre. Individuals were classified as obese insulin resistant (n = 65) if their HOMA was ≥90th percentile for lean individuals (lean, n = 232). Individuals who were lean but also insulin resistant were not included, leaving 46 obese non-insulin-resistant individuals.

Leptin level was determined with the Linco Research human leptin assay. This uses 125I-labelled human leptin and a human leptin antiserum to determine the level of leptin in serum by the double antibody/anti-polyethylene glycol (PEG) antibody technique.

Other covariates collected included fasting lipid panel (US National Heart Lung and Blood Institute-Centers for Disease Control [NHLBI-CDC] standardised method, LDL-cholesterol calculated with Friedewald equation) and C-reactive protein (CRP, high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

BP and brachial artery distensibility

The average of three resting measures of systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), heart rate and brachial artery distensibility (BrachD) obtained (DynaPulse Pathway, PulseMetric, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described were used in analyses [7]. BrachD is calculated via a validated reproducible method of pulse wave form analysis [7] that is independent of body size and baseline brachial artery diameter. Repeat measures in our laboratory show excellent reproducibility with coefficients of variability <9% [4].

Augmentation index and pulse wave velocity

The average of three measures of the augmentation index (AIx) and pulse wave velocity (PWV) obtained with the SphygmoCor SCOR-PVx System (Atcor Medical, Sydney, NSW, Australia) as previously described [4] were used in analyses. The device uses a validated generalised transfer function to calculate central (aortic) SBP, DBP, mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse pressure (PP) and AIx adjusted to a heart rate of 75 bpm. For PWV, the average of two measures of carotid to sternal notch to femoral artery distance was entered into the software. Arterial waveforms gated to the R wave on the ECG tracing were recorded from the carotid and then femoral pulse. PWV is the difference in the carotid-to-femoral path length divided by the difference in timing from the R wave on the ECG to the foot of the pressure waveforms. The transfer function has not been validated against invasive measures in children and adolescents. However, our previous data on healthy paediatric patients (age 3 to 18 years) undergoing catheterisation for atrial septal defect closure resulted in a transfer function with the same peak at the fourth harmonic as demonstrated by Nichols and O’Rourke [8] suggesting the validity of this technique [9]. Reproducibility studies in our laboratory demonstrated intra-class correlation coefficients for AIx between 0.7 and 0.9 and coefficients of variability for PWV <7% [4].

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed with statistical analyses software (SAS, version 9.12). Average values for demographic, anthropometric, laboratory and haemodynamic variables were obtained overall and by obesity/IR group. Variables were log transformed as needed for variance stabilisation. ANOVA was performed to evaluate mean differences by group. To correct for multiple comparisons among the three groups, p values ≤0.017 were considered significant. Multiple regression modelling was performed to determine if IR (HOMA), treated as a continuous variable, was an independent determinant of the three measures of arterial stiffness even after adjusting for CV risk factors. Potential candidates for each regression model were included if they were significantly correlated with arterial stiffness in bivariate analyses and there was no evidence for excess co-linearity with other variables. The most consistent correlates of arterial stiffness were race, BMI, BP, glucose, insulin, HOMA, CRP, adiponectin and leptin. For wave reflection, correlates were age, sex, race, BMI, BP, insulin, HOMA, CRP and leptin. Variable correlations were found for lipid variables. Therefore, the full model included group, age, race, sex, BMI, MAP, heart rate, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerol, HOMA, CRP, adiponectin and leptin. Each variable was allowed to enter the model with non-significant variables removed until all remaining covariates were significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Results

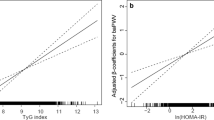

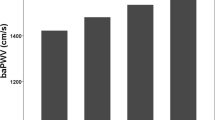

Mean values by obesity and IR group are presented in Table 1. The obese insulin-resistant group had a more adverse CV risk profile than the lean group for all variables. The obese insulin-resistant group also differed from the non-insulin-resistant obese group, with high levels of adverse lipids and higher HOMA. Obese non-insulin-resistant individuals had higher BMI, BP, CRP and leptin, and lower adiponectin, than lean individuals (all p ≤ 0.017). All three vascular measures showed greater arterial stiffness in the obese insulin-resistant group compared with the lean individuals (Table 1 and Fig. 1). BrachD was lower and PWV was higher (indicating greater stiffness) in obese as compared with lean groups (all p ≤ 0.017). After adjustment for race and MAP to control for distending pressure, there was no difference in AIx by group but the relationships remained for BrachD and PWV. Additional adjustment for BMI abolished any differences in arterial stiffness by group (all models p ≤ 0.001, data not shown). Obesity (BMI) and IR (HOMA index) correlated strongly with each other (r = 0.56, p ≤ 0.0001) and CV risk factors including BP, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerol, CRP, adiponectin and leptin (r = 0.14–0.67, all p ≤ 0.002, data not shown).

Arterial stiffness by obesity and IR. a AIx (higher = stiffer). p ≤ 0.015 for lean and obese < obese insulin resistant. b BrachD (lower = stiffer). p ≤ 0.015 for lean > obese and obese insulin resistant. c PWV (higher = stiffer). p ≤ 0.015 for lean < obese and obese insulin resistant. Obese IR, obese insulin resistant

Although insulin-resistant individuals had a more adverse CV risk profile and stiffer arteries, stepwise regression (Table 2) revealed that HOMA index was not an independent determinant of arterial stiffness. Age, sex, BMI and BP were the most consistent determinants, with HDL-cholesterol playing a role in BrachD and leptin in PWV values. When leptin was left out of the models, no additional variables entered the model and the total R 2 for PWV was reduced. The adiponectin/leptin ratio entered the model with no change in variable estimates, suggesting that the leptin term was the most important (data not shown). When the initial full model was examined prior to removal of non-significant variables, no additional covariates had variable estimates with p values near the level of significance (p ≤ 0.10) except for PWV, for which heart rate, LDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerol and CRP were initially significant. The reduced model is presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Our results confirm that a more adverse CV risk profile and stiffer arteries are found in young obese individuals with IR. However, IR, as measured by the HOMA-IR index, was not an independent determinant of any of our measures of arterial stiffness. Rather, obesity, BP and other CV risk factors appeared to be mediating the vascular compromise.

Many adult studies demonstrate a link between obesity and vascular dysfunction. Reduced distensibility in the brachial, femoral and carotid arteries was related to a larger trunk fat mass as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) in the Hoorn study, a large population-based cohort examining the relationships between glucose tolerance and CV disease [10]. Zebekakis et al. [11] found a similar relationship in a somewhat younger population. In fact, the association between adiposity, as measured by BMI, and brachial distensibility was stronger in younger individuals (<40 years). In a similar study of middle-aged adults, researchers found elevated arterial stiffness (higher PWV) with greater BMI and waist–hip ratio [12]. However, in the study by Zebekakis et al., the relationship between PWV and adiposity was independent of BP only for women [11]. They suggested that a more precise measure of adiposity might have demonstrated a relationship for both sexes, as seen when abdominal visceral fat was measured with computed tomography (CT) in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study [13]. Data linking AIx to adiposity are less clear, with some studies demonstrating no relationship [14], while another found a link only after correction for other CV risk factors [15]. Again, method of determining adiposity may play a role, as one investigator found body fat measured with bioelectrical impedance, but not BMI, to be associated with AIx [16].

Few paediatric studies of arterial stiffness have been performed. However, our previous work [4, 17] has consistently demonstrated a relationship between BrachD and adiposity in children. Other studies using different methods to measure brachial artery function than employed in our research (wall tracker [18]) also found obesity to be an important determinant. More studies have employed PWV to measure arterial stiffness in youth. The CV Risk in Young Finns Study showed a higher PWV measured in adulthood with increasing numbers of CV risk factors measured in childhood, including obesity [19]. Other investigators have been able to correlate BMI with PWV measured in childhood [20] and one large study of 573 healthy children found the relationship to be independent of other CV risk factors [21]. The single study that did not find a correlation [22] was performed in a younger group of children (average age 10 years) who had a much lower BMI (mean 17 kg/m2) than our cohort. Our data extend these observations by demonstrating an independent relationship between BMI and arterial stiffness in a larger group of young individuals with PWV measured in the central arterial distribution (carotid–femoral), which is more closely related to hard CV events (coronary death or myocardial infarction) in adults [2]

Adults with diabetes have higher PWV than healthy controls [23], although vascular damage may begin before progression to type 2 diabetes, as HOMA-IR was independently associated with peripheral arterial disease even in healthy individuals in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [24]. Although adult studies have found IR to be independently associated with PWV, the methods used differed substantially from those in our study, and included use of a device that measures brachial–ankle PWV [25], which results in much higher absolute values than the traditional carotid–femoral PWV. Another investigator found that fasting glucose was an independent determinant of PWV but that the variable estimates for BP indicated a much stronger effect [26], mirroring our results and suggesting a stronger role for BP than metabolic control in determining arterial stiffness. Fewer data relate diabetes and IR to brachial artery properties and AIx. Megnien et al. found lower brachial compliance measured under isobaric conditions in diabetic individuals as compared with controls [27] and fasting glucose negatively correlated with compliance. Although Henry et al. found that individuals with impaired glucose tolerance had lower BrachD than normal controls [28], his later work found no differences between individuals with or without metabolic syndrome when stratified by sex [29]. For AIx, one study found no difference between persons with or without diabetes but they had examined a mixture of individuals with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [23]. Another found increased AIx in females with metabolic syndrome, but not in males [30]. However, this study was conducted in hypertensive adults and did not adjust for the known sex differences in AIx, as was done in our models.

In Japanese children, HOMA-IR was found to be an independent determinant of brachial–ankle PWV [31]. However, there were substantial differences between these studies and our own data beyond the PWV technique and race differences. Our participants were older and heavier, which may substantially influence HOMA-IR results. Using ultrasound to measure PWV, Gungor et al. found increasing arterial stiffness in obese youth with further increase in type 2 diabetes [20]. Although multiple regression found HOMA-IR to be an independent predictor, lean individuals were excluded from the analysis and BP and adiposity were not included in the model [20]. Using an optical method to measure PWV, Schack-Nielsen et al. did not find PWV to be associated with HOMA-IR [22]. However, these 10-year-old children were significantly younger and lighter than our study population. Again, data on the brachial artery and AIx in children are also limited. Whincup et al. [18] did see a relationship between IR and brachial distensibility, but only among the 13- to 15-year-old group, and not the 9- to 11-year-olds. The one study that examined AIx found no relation to glucose tolerance but included only 44 children, and may have been underpowered to demonstrate differences [32]. Our study expands the observations on the relationship between IR and arterial stiffness to a population more representative of American youth.

Increased leptin levels have been associated with obesity in youth [33]. Some investigators suggest that leptin/adiponectin ratio is a more sensitive indicator of IR than HOMA-IR [34]. We found an inverse relationship between leptin level and PWV, although the effect size was quite small. Although some investigators have found a positive relationship between leptin and PWV [35], others found no relationship with carotid intima–media thickness [36], and in one large study, there was no relationship between these adipocytokines and coronary heart disease mortality [37]. Additional studies are needed to further explore these findings.

Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow determination of the time course for the development of the vascular associations seen. Therefore, we cannot prove that there is a decline in vascular function as an individual gains adiposity. Our obese and obese insulin-resistant groups also had a greater proportion of non-white individuals, which may have influenced our results. Another potential source of selection bias was our exclusion of lean insulin-resistant individuals. This type of individual constituted only 2.8% of the school-based population from which our participants were recruited, making it unlikely that there would have been sufficient numbers to demonstrate differences in arterial stiffness from the other groups. More precise methods for assessing adiposity and body fat distribution, such as DEXA or CT, were not feasible in this school-based cohort. Therefore, it is not possible to determine if body composition was an independent determinant of arterial stiffness. Finally, normal values for arterial stiffness across age, sex and race are not available for youths, limiting the usefulness of these measures in risk stratification.

Conclusion

We conclude that although obesity-related IR is associated with increased arterial stiffness, it is the more adverse CV risk profile that is actually driving the vascular compromise in non-diabetic, otherwise healthy, young people. The practice of ‘primordial prevention’, which relies on prevention of acquisition of CV risk factors, especially aggressive early treatment of obesity, is needed to avoid the vascular dysfunction in youth that may lead to future heart attack and stroke.

Abbreviations

- AIx:

-

Augmentation index

- BrachD:

-

Brachial artery distensibility

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- DBP:

-

Diastolic BP

- DEXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- PP:

-

Pulse pressure

- PWV:

-

Pulse wave velocity

- SBP:

-

Systolic BP

References

Gersh BJ, Sliwa K, Mayosi BM, Yusuf S (2010) Novel therapeutic concepts: the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in the developing world: global implications. Eur Heart J 31:642–648

Cruickshank K, Riste L, Anderson SG, Wright JS, Dunn G, Gosling RG (2002) Aortic pulse-wave velocity and its relationship to mortality in diabetes and glucose intolerance: an integrated index of vascular function? Circulation 106:2085–2090

De Silva DA, Woon FP, Gan HY et al (2008) Arterial stiffness, metabolic syndrome and inflammation amongst Asian ischaemic stroke patients. Eur J Neurol 15:872–875

Urbina EM, Kimball TR, Khoury PR, Daniels SR, Dolan LM (2010) Increased arterial stiffness is found in adolescents with obesity or obesity-related type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Hypertens 28:1692–1698

Goodman E, Dolan LM, Morrison JA, Daniels SR (2005) Factor analysis of clustered cardiovascular risks in adolescence: obesity is the predominant correlate of risk among youth. Circulation 111:1970–1977

Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B et al (2002) Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med 346:802–810

Brinton TJ, Cotter B, Kailasam MT, Brown DL, Chio S-S, O’Conor DT, DeMaria AN (1997) Development and validation of a noninvasive method to determine arterial pressure and vascular compliance. Am J Cardiol 80:323–330

Nichols WW, O’Rourke MF (2005) McDonald’s blood flow in arteries: theoretical, experimental, and clinical principles. Hodder Arnold, London

Urbina EM, Dolan LM, McCoy CE, Khoury PR, Daniels SR, Kimball TR (2011) Relationship between elevated arterial stiffness and increased left ventricular mass in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr 158:715–721

Snijder MB, Henry RM, Visser M et al (2004) Regional body composition as a determinant of arterial stiffness in the elderly: the Hoorn Study. J Hypertens 22:2339–2347

Zebekakis PE, Nawrot T, Thijs L et al (2005) Obesity is associated with increased arterial stiffness from adolescence until old age. J Hypertens 23:1839–1846

Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A, Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K (2003) Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension 42:468–473

Sutton-Tyrrell K, Newman A, Simonsick EM et al (2001) Aortic stiffness is associated with visceral adiposity in older adults enrolled in the Study of Health, Aging, and Body Composition. Hypertension 38:429–433

Dengo AL, Dennis EA, Orr JS et al (2010) Arterial destiffening with weight loss in overweight and obese middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension 55:855–861

Otsuka T, Kawada T, Ibuki C et al (2009) Obesity as an independent influential factor for reduced radial arterial wave reflection in a middle-aged Japanese male population. Hypertens Res Clin Exp 32:387–391

Wykretowicz A, Adamska K, Guzik P et al (2007) Indices of vascular stiffness and wave reflection in relation to body mass index or body fat in healthy subjects. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34:1005–1009

Urbina EM, Bean JA, D’Alessio D, Daniels SR, Dolan LM (2007) Overweight and hyperinsulinemia provide individual contributions to compromises in brachial artery distensibility in healthy adolescents and young adults. J Am Soc Hypertens 1:200–207

Whincup PH, Gilg JA, Donald AE et al (2005) Arterial distensibility in adolescents: the influence of adiposity, the metabolic syndrome, and classic risk factors. Circulation 112:1789–1797

Aatola H, Hutri-Kahonen N, Juonala M et al (2010) Lifetime risk factors and arterial pulse wave velocity in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Hypertension 55:806–811

Gungor N, Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Janosky J, Arslanian S (2005) Early signs of cardiovascular disease in youth with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 28:1219–1221

Sakuragi S, Abhayaratna K, Gravenmaker KJ et al (2009) Influence of adiposity and physical activity on arterial stiffness in healthy children: the Lifestyle of our Kids Study. Hypertension 53:611–616

Schack-Nielsen L, Molgaard C, Larsen D, Martyn C, Michaelsen KF (2005) Arterial stiffness in 10-year-old children: current and early determinants. Br J Nutr 94:1004–1011

Lacy PS, O’Brien DG, Stanley AG, Dewar MM, Swales PP, Williams B (2004) Increased pulse wave velocity is not associated with elevated augmentation index in patients with diabetes. J Hypertens 22:1937–1944

Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA (2008) Association of insulin resistance and inflammation with peripheral arterial disease: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Circulation 118:33–41

Kasayama S, Saito H, Mukai M, Koga M (2005) Insulin sensitivity independently influences brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity in non-diabetic subjects. Diabet Med 22:1701–1706

Czernichow S, Bertrais S, Blacher J et al (2005) Metabolic syndrome in relation to structure and function of large arteries: a predominant effect of blood pressure. A report from the SU.VI.MAX. Vascular Study. Am J Hypertens 18:1154–1160

Megnien JL, Simon A, Valensi P, Flaud P, Merli I, Levenson J (1992) Comparative effects of diabetes mellitus and hypertension on physical properties of human large arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:1562–1568

Henry RMA, Kostense PJ, Spijkerman AMW et al (2003) Arterial stiffness increases with deteriorating glucose tolerance status: the Hoorn study. Circulation 107:2089–2095

Henry RM, Ferreira I, Dekker JM et al (2009) The metabolic syndrome in elderly individuals is associated with greater muscular, but not elastic arterial stiffness, independent of low-grade inflammation, endothelial dysfunction or insulin resistance—the Hoorn Study. J Hum Hypertens 23:718–727

Protogerou AD, Blacher J, Aslangul E et al (2007) Gender influence on metabolic syndrome's effects on arterial stiffness and pressure wave reflections in treated hypertensive subjects. Atherosclerosis 193:151–158

Miyai N, Arita M, Miyashita K, Morioka I, Takeda S (2009) The influence of obesity and metabolic risk variables on brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in healthy adolescents. J Hum Hypertens 23:444–450

Khan F, Kerr H, Ross RA, Newton DJ, Belch JJ, Belch JJF (2006) Effects of poor glucose handling on arterial stiffness and left ventricular mass in normal children. Int Angiol 25:268–273

Diamond FB Jr, Cuthbertson D, Hanna S, Eichler D (2004) Correlates of adiponectin and the leptin/adiponectin ratio in obese and non-obese children. J Pediatr Endocrinol 17:1069–1075

Zaletel J, Barlovic DP, Prezelj J (2010) Adiponectin–leptin ratio: a useful estimate of insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Invest 33:514–518

Windham BG, Griswold ME, Farasat SM et al (2010) Influence of leptin, adiponectin, and resistin on the association between abdominal adiposity and arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens 23:501–507

Bevan S, Meidtner K, Lorenz M, Sitzer M, Grant PJ, Markus HS (2011) Adiponectin level as a consequence of genetic variation, but not leptin level or leptin: adiponectin ratio, is a risk factor for carotid intima–media thickness. Stroke 42:1510–1514

Karakas M, Zierer A, Herder C et al (2010) Leptin, adiponectin, their ratio and risk of coronary heart disease: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Study 1984–2002. Atherosclerosis 209:220–225

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of the Princeton School District research team and the administration, staff, teachers, students and parents of the Princeton School District.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants K23 HL080447-01A1 (Mechanisms of Vascular Dysfunction in Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome) and by USPHS #UL1 RR026314 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH.

Duality of interest

The authors declare there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

EMU designed the study, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the article and revised it. ZG and PRK analysed the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. LJM and LMD helped design the study and interpret the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urbina, E.M., Gao, Z., Khoury, P.R. et al. Insulin resistance and arterial stiffness in healthy adolescents and young adults. Diabetologia 55, 625–631 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2412-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2412-1