Abstract

Purpose

What happens to the transference of learning proper jump-landing technique in isolation when an individual is expected to perform at a competitive level yet tries to maintain proper jump-landing technique? This is the key question for researchers, physical therapists, athletic trainers and coaches involved in ACL injury prevention in athletes. The need for ACL injury prevention is clear, however, in spite of these ongoing initiatives and reported early successes, ACL injury rates and the associated gender disparity have not diminished. One problem could be the difficulties with the measurements of injury rates and the difficulties with the implementation of thorough large scale injury prevention programs. A second issue could be the transition from conscious awareness during training sessions on technique in the laboratory to unexpected and automatic movements during a training or game involves complicated motor control adaptations. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the issue of motor learning in relation to ACL injury prevention and to post suggestions for future research.

Conclusion

ACL injury prevention programs addressing explicit rules regarding desired landing positions by emphasizing proper alignment of the hip, knee, and ankle are reported in the literature. This may very well be a sensible way, but the use of explicit strategies may be less suitable for the acquisition of the control of complex motor skills (Maxwell et al. J Sports Sci 18:111–120, 2000). Sufficient literature on motor learning and it variations point in that direction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

ACL injury prevention training strategies mainly focussing on warm-up, technique, balance, strengthening, and agility exercises have continued to evolve and represent an ever-increasing and equally important research focus [12, 14, 21–23, 29, 30, 40, 42, 43, 48, 53, 65]. Recent epidemiological data, however, suggest that in spite of these ongoing initiatives and reported early successes, ACL injury rates and the associated gender disparity have not diminished [2]. The disparity between positive laboratory results and actual effects on injury outcomes suggests a missing link between current research outcomes and clinical applications for neuromuscular training interventions. One problem could be the difficulties with the measurements of injury rates and the difficulties with the implementation of thorough large-scale injury prevention programs. It is difficult to evaluate whether the preventive measure had any effect at all when we know very little about whether sports-active people have implemented or adopted information about preventive training or not. Another issue could be the fact that the transition from conscious awareness during training sessions to unexpected and automatic movements during a training or game involves complicated motor control adaptations. Post-intervention lower extremity positions and loading of the joint in the laboratory do not necessary reflect those on the field. The purpose of this paper is therefore to highlight the issue of motor learning in relation to ACL injury prevention and to post suggestions for future research.

Implicit versus explicit motor learning

Instructions can be effective in conveying goal-related information and educators commonly use them to teach and refine motor performance at all levels of skill [25]. There are ACL injury prevention programs using instructions and addressing explicit rules regarding desired landing positions by emphasizing proper alignment of the hip, knee, and ankle [22, 23, 26, 28, 30, 40, 41, 43, 46, 48, 51–53]. For example, the main goal of the neuromuscular training program of Holm et al. was ‘to improve awareness and knee control during standing, cutting, jumping, and landing’. The players were encouraged to focus on the quality of their movements with emphasis on the knee-over-toe position [26].

This may very well be a sensible way, but the use of explicit strategies may be less suitable for the acquisition of the control of complex motor skills [34]. It has been shown that instructions that direct performers’ attention to his or her own movements can actually have a detrimental effect on performance and learning and disrupt the execution of automatic skills, particularly in comparison with an externally directed attentional focus [33, 37, 67–69]. We want to emphasize that we need to make sure that a better landing technique after a jump happens automatically. Therefore, pre-programming with automatization with transfer for laboratory to field is most important.

The exact reasons for the beneficial effects of an external focus of attention are still relatively unclear. However, trying to consciously control one’s movements might interfere with the normal, automatic motor control processes, leading to a breakdown in the natural coordination of the movement [32, 37].

The performance and learning of motor skills has been shown to be enhanced if the performer adopts an external focus of attention (focus on the movement effect) compared to an internal focus (focus on the movements themselves) [68]. In other words, implicit motor learning refers to the acquisition of a motor skill without the concurrent acquisition of explicit knowledge about the performance of a skill that is normally processed in an automatic way, explicit motor learning does refer to acquiring motor skills with an internal focus and specific knowledge about the performance of a skill [34]. Motor skills that are acquired explicitly tend to be less resilient under psychological [7, 18, 19, 32, 39] and physiological fatigue [31, 54], tend to interfere with the normal automatic processing of the motor schema [20, 32], tend to be less durable [5] and less robust [66] when a fast response is required and explicit learning may be affected to a greater extent by an individual’s intelligence than implicit learning [17, 45, 57].

Considering the benefits of implicit learning, we feel that in the prevention of ACL injuries, we need to discover the possibilities of this method as it may produce more stable solutions under stress, anxiety-provoking conditions and fatigued states. The research group McNair, Onate and Prapavessis set up an interesting series of research projects, in which they examined the effect of different types of feedback on jump landing technique and subsequent landing forces [36, 49, 50, 55, 56]. The patterns shown in their results confirmed the theory mentioned earlier. They have compared technical instructions, visual feedback, auditory cues, and metaphoric imagery to controls. They first found that subjects can assimilate precise instructions related to the modification of lower limb kinematics and effectively and immediately lowered their ground reaction forces (GRF) [36, 50, 55]. However, in 2003 Prapavessis et al. found that the retention of these technical instructions is poor when the follow up is longer than 1 week [56]. Continuing this research, Onate et al. concluded in 2005 that reviewing one’s own performance or one’s own performance plus an expert model is more useful than expert only modeling (i.e., viewing an expert model trained in proper landing technique) for increasing knee angular displacement flexion angles and reducing peak vertical GRF during landing. They therefore suggested that visual feedback of one’s own performance or one’s own performance plus an expert model should be used in the implementation of instructional programs aimed at reducing the risk of jump-landing ACL injuries [49].

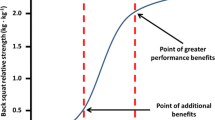

Currently, we do not know yet at what age an injury prevention program should be implemented to reduce potential neuromuscular and biomechanical risk factors [64]. From a motor learning standpoint, it is desirable that children at the youngest age groups (age 6–12) develop correct playing techniques from the beginning on. This also gives ample time for movements to become automatized. However, children are at a relative low risk for injury, e.g., soccer is actually a safe sport for children [16]. It seems therefore that spending effort, time, and money on implementing preventive methods might therefore not be desirable and should potentially start from 12 to 14 years [44]. But without calling it injury prevention (but e.g., exercises for performance enhancement [44]) in the younger age groups, enhanced body awareness will very likely already start and result in a more complete and accurate feeling of the body when learning certain movement skills.

Transfer from the laboratory to the field

The use of an explicit process is less efficient, attention-demanding, and slow [34]. Having to pay attention to the lower extremity is impossible as attention to the game, players and ball and fast acting is required. A high-cognitive task will be less robust during the game.

In the ACL injury enigma, psychological and physiological pressure or fatigue is an important factor. Myklebust et al. reported that athletes are at a higher risk of suffering an ACL injury during a game than during practice [43]. Fatigue has also been proposed to be a contributor to non-contact ACL injuries [24, 47, 61]. For obvious reasons, a game constitutes more psychological and physiological stress compared to a practice session. Especially in later stages of competition, fatigue may have a cumulative, unfavorable effect on neuromuscular control and may potentially result in hazardous movement strategies [35]. The decreased capacity for controlling body movements after fatigue will potentially be more prominent when appropriate landing techniques have been taught in an explicit manner. Also, the possibility that implicit learning may immunize the athlete more against the often debilitating influence of psychological stress on motor output should not go unheeded.

In summary, extensively repeating the ideal movement that is explained and demonstrated might be too ‘cognitive’. As implicit learning has proven to be effective in establishing a certain movement goal or effect [37, 62, 67–69], we assume and propose that implicit motor learning might also be potentially beneficial for injury prevention. Lowering chances of injury during a high performance task is an integrated part of that task itself. This implies that not only the interaction with the environment can be optimized but also the conditions within the body in terms of balance of joint loads for instance. This optimization could be achieved by assisting the athletes to find individual optimal performance patterns for given complex motor skills and to find an individual way, including its effective variations, to control the forces that belong to those complex tasks. In this paper, we would like to put forward that implicit learning could well be an effective way to let the brain and body of the athlete reach a condition in which performance is high, yet the chances of injury low.

Mirror neuron system

Implicit, observational learning, where imitation of what is shown plays an important role, might be a good alternative in trying to reduce the ACL injury incidence. Imitation is the copying of body movements that are observed [8]. A fundamental question with imitation is: “How does the observer’s motor system ‘know’ which muscle activations will lead to the observed movement if the observer does not see the underlying muscle activation in the actor?” [8]. It has been suggested that the mirror neurons resolve this correspondence problem by automatically mapping observed movements onto a motor program, thus leading to the widely held view that the mirror neuron system is crucial for imitation and observational learning [9, 13, 27, 38, 58–60]. Mirror neurons are visuomotor neurons that fire both when an action is performed and when a similar or identical action is passively observed [59]. A template of the movement becomes active through the mirror neurons by which the movement itself becomes clear in terms of motor actions, without high cognitive reflections [60]. Mirror neurons mediate understanding of action because neurons that represent an action are activated in the observer’s premotor cortex. This automatically induced, motor representation of the observed action corresponds to that which is spontaneously generated during active action and whose outcome is known to the acting individual. An important functional aspect of mirror neurons is therefore their ability to link visual and motor properties.

It is interesting to note that the amount of mirror neuron activation correlates positively when the athletes are already proficient in performing that skill [10]. Also, stronger mirror neuron activation is found when observing the same gender [11]. An additional prospective study showed that dancers who were initially naive to certain steps showed an increase in mirror activation over time when they received motor training in which they became skillful in performing the same steps [15].

Implications for ACL injury prevention and future research

The previously mentioned studies [36, 49, 50, 55, 56] offer a direction for the development of a method of ACL injury prevention, based on implicit learning. They indicate that the solution to injury prevention is hidden in the brains of the subjects themselves. That solution needs to be awakened by a proper intervention of implicit learning. Since every brain and every body is different, the optimal solutions are also different. Future research should provide more detailed information on the way these solutions are linked to certain types of body architecture and motor control capacities. Long term effects of visual feedback need to be explored. The results support the need for individualized visual augmented feedback using a self model to enhance jump-landing instruction and substantiates that this works best in the motor learning process [36]. The ability for individuals to view themselves performing correctly or making mistakes and responding to the corrections is of greater value to individuals than is viewing an expert model performing the task correctly. One theoretical approach is that learning is a problem-solving process; the more involved the individual is in analyzing his or her own performance, the greater the learning value [1, 63]. With implicit learning the position of the knee will be part of the position of the whole body. The subject will explore and then select the solution that fits best in their body.

Preventive studies we have referred to in this article mostly contain exercises that improve performance and reduce injuries by improving strengthening and conditioning. From these investigations, we have learned that ACL injuries can be prevented by a combination of balance/coordination, strength, plyometric and agility exercises [3, 4]. Immediate feedback of someone’s own performance is an area which is still relatively unexplored and can aid in achieving long term results.

For laboratory studies, one’s performance could be recorded with a high-speed camera from a posterior view (in order to give the right perspective to the athlete). When using infrared camera’s and a force plate, 3D load at the knee can be calculated through inverse dynamics and the best performance so far can be presented to the subject without any explicit instructions on the lower extremity position. For on-field training, a simple camera could be used and with user-friendly software, the athlete’s own performances could be reviewed and improved.

Conclusion

The transition from conscious awareness during technique training sessions to unexpected and automatic movements during a training or game involves complicated motor control elements that might not fit in explicit learning strategies [6]. We therefore encourage to explore the use of implicit learning in ACL injury prevention. Future ACL intervention programs may need to provide individualized visual instructional review of jump-landing technique to allow individuals to view how they personally perform the movement task and actively problem solve (by evaluating the mistakes and corrections of their trials) to develop techniques, and find individual ways to achieve those techniques, to obtain proper jump-landing. There is a need for further development of the learning model of visual demonstration and real time feedback. At any rate, the effects of attentional focus on motor performance not only provide interesting insights into the effectiveness of automatic control capabilities of the motor system, but they also have important implications for performance improvements in applied settings.

References

Adams J (1971) A closed loop theory of motor learning. J Mot Behav 3:111–150

Agel J, Arendt EA, Bershadsky B (2005) Anterior cruciate ligament injury in national collegiate athletic association basketball and soccer: a 13-year review. Am J Sports Med 33:524–530

Alentorn-Geli E, Myer GD, Silvers HJ, Samitier G, Romero D, Lazaro-Haro C, Cugat R (2009) Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players. Part 1: mechanisms of injury and underlying risk factors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:705–729

Alentorn-Geli E, Myer GD, Silvers HJ, Samitier G, Romero D, Lazaro-Haro C, Cugat R (2009) Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players. Part 2: a review of prevention programs aimed to modify risk factors and to reduce injury rates. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:859–879

Allen R, Reber A (1980) Very long-term memory for tacit knowledge. Cognition 8:175–185

Beek PJ (2000) Toward a theory of implicit learning in the perceptual-motor domain. Int J Sport Psychol 31:547–554

Beilock SL, Carr TH (2001) On the fragility of skilled performance: what governs choking under pressure? J Exp Psychol Gen 130:701–725

Brass M, Heyes C (2005) Imitation: is cognitive neuroscience solving the correspondence problem? Trends Cogn Sci 9:489–495

Buccino G, Binkofski F, Riggio L (2004) The mirror neuron system and action recognition. Brain Lang 89:370–376

Calvo-Merino B, Glaser D, Grèzes J, Passingham R, Haggard P (2005) Action observation and acquired motor skills: an FMRI study with expert dancers. Cereb Cortex 15:1243–1249

Calvo-Merino B, Grezes J, Glaser D, Passingham R, Haggard P (2006) Seeing or doing? Influence of visual and motor familiarity in action observation. Curr Biol 16:1905–1910

Caraffa A, Cerulli G, Projetti M, Aisa G, Rizzo A (1996) Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. A prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 4:19–21

Cattaneo L, Rizzolatti G (2009) The mirror neuron system. Arch Neurol 66:557–560

Chimera NJ, Swanik KA, Swanik CB, Straub SJ (2004) Effects of plyometric training on muscle-activation strategies and performance in female athletes. J Athl Train 39:24–31

Cross E, Hamilton A, Grafton S (2006) Building a motor simulation de novo: observation of dance by dancers. Neuroimage 31:1257–1267

Froholdt A, Olsen O, Bahr R (2009) Low risk of injuries among children playing organized soccer: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med 37:1155–1160

Gebauer GF, Nicholas JM (2007) Psychometric intelligence dissociates implicit and explicit learning. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 33:34–54

Gray R (2004) Attending to the execution of a complex sensorimotor skill: expertise differences, choking, and slumps. J Exp Psychol Appl 10:42–54

Hardy L, Mullen R, Jones G (1996) Knowledge and conscious control of motor actions under stress. Br J Psychol 87:621–636

Hardy L, Mullen R, Martin N (2001) Effect of task-relevant cues and state anxiety on motor performance. Percept Mot Skills 92:943–946

Heidt RS Jr, Sweeterman LM, Carlonas RL, Traub JA, Tekulve FX (2000) Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. Am J Sports Med 28:659–662

Hewett TE, Lindenfeld TN, Riccobene JV, Noyes FR (1999) The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med 27:699–706

Hewett TE, Stroupe AL, Nance TA, Noyes FR (1996) Plyometric training in female athletes. Decreased impact forces and increased hamstring torques. Am J Sports Med 24:765–773

Hiemstra L, Lo I, Fowler P (2001) Effect of fatigue on knee proprioception: implications for dynamic stabilization. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 31:598–605

Hodges N, Franks I (2002) Modelling coaching practice: the role of instruction and demonstration. J Sports Sci 20:793–811

Holm I, Fosdahl MA, Friis A, Risberg MA, Myklebust G, Steen H (2004) Effect of neuromuscular training on proprioception, balance, muscle strength, and lower limb function in female team handball players. Clin J Sport Med 14:88–94

Iacoboni M (2005) Neural mechanisms of imitation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15:632–637

Irmischer B, Harris C, Pfeiffer R, DeBeliso M, Adams K, Shea K (2004) Effects of a knee ligament injury prevention exercise program on impact forces in women. J Strength Cond Res 18:703–707

Lephart SM, Abt JP, Ferris CM, Sell TC, Nagai T, Myers JB, Irrgang JJ (2005) Neuromuscular and biomechanical characteristic changes in high school athletes: a plyometric versus basic resistance program. Br J Sports Med 39:932–938

Mandelbaum BR, Silvers HJ, Watanabe DS, Knarr JF, Thomas SD, Griffin LY, Kirkendall DT, Garrett W Jr (2005) Effectiveness of a neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 33:1003–1010

Masters R, Poolton J, Maxwell J (2008) Stable implicit motor processes despite aerobic locomotor fatigue. Conscious Cogn 17:335–338

Masters RSW (1992) Knowledge, “knerves” and know-how: the role of explicit versus implicit knowledge in the breakdown of a complex motor skill under pressure. Br J Psych 83:343–358

Masters RSW, Poolton JM, Maxwell JP, Raab M (2008) Implicit motor learning and complex decision making in time-constrained environments. J Mot Behav 40:71–79

Maxwell JP, Masters RSW, Eves F (2000) From novice to no know-how: a longitudinal study of implicit motor learning. J Sports Sci 18:111–120

McLean SG, Fellin RE, Suedekum N, Calabrese G, Passerallo A, Joy S (2007) Impact of fatigue on gender-based high-risk landing strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:502–514

McNair P, Prapavessis H, Callender K (2000) Decreasing landing forces: effects of instruction. Br J Sports Med 34:293–296

McNevin NH, Wulf HG, Carlson C (2000) Effects of attentional focus, self-control, and dyad training on motor learning: implications for physical rehabilitation. Phys Ther 80:373–385

Molenberghs P, Cunnington R, Mattingley J (2009) Is the mirror neuron system involved in imitation? A short review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:975–980

Mullen R, Hardy L, Oldham A (2007) Implicit and explicit control of motor actions: revisiting some early evidence. Br J Psychol 98:141–156

Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE (2006) The effects of plyometric vs. dynamic stabilization and balance training on power, balance, and landing force in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res 20:345–353

Myer GD, Ford KR, McLean SG, Hewett TE (2006) The effects of plyometric versus dynamic stabilization and balance training on lower extremity biomechanics. Am J Sports Med 34:445–455

Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo JP, Hewett TE (2005) Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res 19:51–60

Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Braekken IH, Skjolberg A, Olsen OE, Bahr R (2003) Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: a prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clin J Sport Med 13:71–78

Myklebust G, Steffen K (2009) Prevention of ACL injuries: how, when and who? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:857–858

Nemeth D, Janacsek K, Balogh V, Londe Z, Mingesz R, Fazekas M, Jambori S, Danyi I, Vetro A (2010) Learning in autism: implicitly superb. PLoS One 5:e11731

Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Fleckenstein C, Walsh C, West J (2005) The drop-jump screening test: difference in lower limb control by gender and effect of neuromuscular training in female athletes. Am J Sports Med 33:197–207

Nyland JA, Shapiro R, Caborn DN, Nitz AJ, Malone TR (1997) The effect of quadriceps femoris, hamstring, and placebo eccentric fatigue on knee and ankle dynamics during crossover cutting. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 25:171–184

Olsen OE, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Holme I, Bahr R (2005) Exercises to prevent lower limb injuries in youth sports: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 330:449

Onate JA, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Giuliani C, Yu B, Garrett WE (2005) Instruction of jump-landing technique using videotape feedback: altering lower extremity motion patterns. Am J Sports Med 33:831–842

Onate JA, Guskiewicz KM, Sullivan RJ (2001) Augmented feedback reduces jump-landing forces. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 31:511–517

Petersen W, Braun C, Bock W, Schmidt K, Weimann A, Drescher W, Eiling E, Stange R, Fuchs T, Hedderich J, Zantop T (2005) A controlled prospective case control study of a prevention training program in female team handball players: the German experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 125:614–621

Pfeiffer RP, Shea KG, Roberts D, Grandstrand S, Bond L (2006) Lack of effect of a knee ligament injury prevention program on the incidence of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:1769–1774

Pollard CD, Sigward SM, Ota S, Langford K, Powers CM (2006) The influence of in-season injury prevention training on lower-extremity kinematics during landing in female soccer players. Clin J Sport Med 16:223–227

Poolton J, Masters R, Maxwell J (2007) Passing thoughts on the evolutionary stability of implicit motor behaviour: performance retention under physiological fatigue. Conscious Cogn 16:456–468

Prapavessis H, McNair P (1999) Effects of instruction in jumping technique and experience jumping on ground reaction forces. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 29:352–356

Prapavessis H, McNair PJ, Anderson K, Hohepa M (2003) Decreasing landing forces in children: the effect of instructions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 33:204–207

Reber AS, Walkenfeld FF, Hernstadt R (1991) Implicit and explicit learning: individual differences and IQ. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 17:888–896

Rizzolatti G (2005) The mirror neuron system and its function in humans. Anat Embryol 210:419–421

Rizzolatti G, Craighero L (2004) The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci 27:169–192

Rizzolatti G, Fogassi L, Gallese V (2001) Neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the understanding and imitation of action. Nat Rev Neurosci 2:661–670

Rodacki AL, Fowler NE, Bennett SJ (2001) Multi-segment coordination: fatigue effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33:1157–1167

Schöllhorn WI, Beckmann H, Michelbrink M, Sechelmann M, Trockel M, Davids K (2006) Does noise provide a basis for the unification of motor learning theories? Int J Sports Psychol 37:186–206

Shea CH, Wulf G (2005) Schema theory: a critical appraisal and reevaluation. J Mot Behav 37:85–101

Shultz S, Schmitz RJ, Nguyen AD, Chaudhari AM, Padua DA, McLean SG, Sigward S (2010) ACL research retreat V: an update on ACL injury risk and prevention, March 25–27, 2010, Greensboro, NC. J Athl Train 45:499–508

Silvers HJ, Mandelbaum BR (2007) Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injury in the female athlete. Br J Sports Med 41(Suppl 1):i52–i59

Turner CW, Fischler IS (1993) Speeded tests of implicit knowledge. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 19:1165–1177

Wulf G, Lauterbach B, Toole T (1999) The learning advantages of an external focus of attention in golf. Res Q Exerc Sport 70:120–126

Wulf G, Prinz W (2001) Directing attention to movement effects enhances learning: a review. Psychon Bull Rev 8:648–660

Wulf G, Weigelt C (1997) Instructions about physical principles in learning a complex motor skill: to tell or not to tell. Res Q Exerc Sport 68:362–367

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Benjaminse, A., Otten, E. ACL injury prevention, more effective with a different way of motor learning?. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19, 622–627 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1313-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1313-z