Abstract

Several studies have provided ample evidence of a clinically significant interobserver variation of the histological diagnosis of glioma. This interobserver variation has an effect on both the typing and grading of glial tumors. Since treatment decisions are based on histological diagnosis and grading, this affects patient care: erroneous classification and grading may result in both over- and undertreatment. In particular, the radiotherapy dosage and the use of chemotherapy are affected by tumor grade and lineage. It also affects the conduct and interpretation of clinical trials on glioma, in particular of studies into grade II and grade III gliomas. Although trials with central pathology review prior to inclusion will result in a more homogeneous patient population, the interpretation and external validity of such trials are still affected by this, and the question whether results of such trials can be generalized to patients diagnosed and treated elsewhere remains to be answered. Although molecular classification may help in typing and grading tumors, as of today this is still in its infancy and unlikely to completely replace histological classification. Routine pathology review in everyday clinical practice should be considered. More objective histological criteria for the grade and lineage of gliomas are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

A case report illustrating the problem

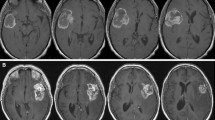

In May 2008, the principal investigator of an EORTC study on anaplastic glioma (CATNON) was contacted by the local investigator of one of the participating institutions. A brain tumor patient operated and diagnosed in a third institution as anaplastic astrocytoma (AA) (Fig. 1a–d) was referred for further treatment, and the local investigator was considering to enter the patient in the CATNON study. However, his own pathologist had diagnosed a low grade astrocytoma. The local investigator asked how this patient should be treated, and if he was eligible for the study or whether he should be entered in another study on low grade glioma. It was decided to submit the tumor material for central pathology review that is part of the CATNON study. This study requires confirmation of the pathological diagnosis by either one of two independent pathologists. The diagnosis of the first central review pathologist for the CATNON study was AA, and because of this the patient was eligible. However, the second central pathologist of the CATNON study felt that this tumor was a low grade astrocytoma. Because confirmation by one pathologist suffices for inclusion in the CATNON study, after the required 1p/19q testing the patient was randomized into this study.

Several issues that potentially influenced the diagnosis were identified in this case: (a) the specimen was of a relatively poor quality (Fig. 1a); (b) the number of mitoses that are acceptable for grade II is unclear (Fig. 1b); (c) some “incipient” microvascular proliferation was observed (Fig. 1c; true microvascular proliferation would grade the tumor as GBM); (d) there are gemistocytes (the acceptability of a substantial number of gemistocytes for grade II is disputed, although in the official WHO 2007 book gemistocytic astrocytoma is still considered grade II (Fig. 1d). Based on these different diagnoses, the patient could have been treated with either 50 or 60 Gy radiotherapy, and could have been entered in two different studies which ask different questions and which employ different (standard) treatment regimens. If he would have been suffering from a low grade tumor that was treated as a high grade tumor, he would be overtreated, if the opposite was true he would be undertreated. The absence of objective external validation makes this problem comparable to the baron of Münchhausen, dragging himself at his tuft out of a marsh (Table 1).

Introduction

A number of studies have firmly established the presence and clinical relevance of interobserver variation in the pathological diagnosis of glioma. In a systematic series on a cohort of 500 brain tumor patients routinely reviewed as a part of daily patient care, some degree of disagreement was present in 42.8%, which was considered serious in 8.8% [2]. Aldape et al. [1] noted discordant diagnoses in 23% of 457 cases referred for the San Francisco Adult Glioma Study, with higher degrees of discordance in cases referred by local community hospitals as opposed to academic hospitals. 16% of the discordant diagnoses were considered to be clinically significant, altering patient management and/or prognosis. In a prospective study on 244 cases reviewed by 4 pathologists, Coons et al. [9] showed that diagnostic concordance can be improved by a repetition of the review process. The four reviewers agreed in only 52% of cases in the initial review, but in 69% of cases after the fourth review. The authors concluded that much of the improvement was related to the refinement of criteria distinguishing diffuse astrocytomas from oligodendrogliomas/oligoastrocytomas and pilocytic astrocytomas, representing distinctions which are clinically quite relevant. This study also suggested that oligodendrogliomas comprised about 25% of all gliomas, although initially only 5% had been diagnosed as oligodendroglioma. This report exemplifies the temporary increase in percentage of diffuse gliomas diagnosed as oligodendroglial in the late 1990s. This trend was reversed only once it became clear that more classical features correlated with the presence of the combined 1p/19q co-deletion associated with increased sensitivity to chemotherapy [3, 16, 21, 27, 30, 36]. One of these studies on the presence of 1p/19q co-deletion in diffuse glioma which reviewed 162 cases noted unanimous agreement among three pathologists for histologic subtype classification in 69% (36 of 52) of oligodendrogliomas, 13% (4 of 31) of mixed oligoastrocytomas, and 76% (60 of 79) of astrocytomas [30]. Several studies more specifically investigated the diagnosis of oligodendroglial tumors. A series of 124 cases of low and high grade oligodendroglioma was used to establish the reproducibility of histological grading criteria between 13 pathologists [12]. Reproducibility appeared to be moderate (κ score 0.41–0.60) or substantial (0.61–0.80) for only some features upon which the WHO grading system is based. These authors also noted that a preliminary written explanation appeared to increase the reproducibility of some of the items, in particular the presence of high cellularity, the presence of mitosis, the number of mitoses per ten HPF, the presence of microcalcifications, endothelial hypertrophy and proliferation and necrosis. For the overall diagnosis of anaplasia, the κ score was well below 0.40. A panel review on 131 tumors showed that in 83% of cases 4 out of 5 pathologists reached consensus on the diagnosis of classical oligodendroglial features [21].

As a conclusion, it seems safe to assume that 20–30% of gliomas are reclassified when the tumor material is independently reviewed. These difficulties in the diagnosis of brain tumors are not to be understood as simple mistakes. The way in which the diagnostic classes of gliomas are described leaves room for subjective interpretation and other variations, as further discussed below. Moreover, the histopathological criteria have changed over time. In the 1990s, the presence of endothelial proliferation even in the absence of necrosis in astrocytic tumors became sufficient to classify these tumors as glioblastoma (GBM). More recently, the presence of necrosis in mixed anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (AOA) became in the WHO 2007 sufficient to classify these tumors as GBM or as glioblastoma with oligodendroglial differentiation (GBM-O) [24, 37]. Both are examples of rather defined changes, described in detail in the WHO classification, although it still leaves room for interpretation (what distinguishes a pure anaplastic oligodendroglioma with necrosis from a mixed AOA with necrosis? How is endothelial proliferation defined?). The studies of Coons et al. that noted oligodendroglioma represent 20–25% of all gliomas present a more difficult and apparently more subjective issue. Of relevance, the authors noted that classical histological features of oligodendroglioma were not required for its diagnosis: the presence of a mucopolysaccharide-rich extracellular fluid, prominent perineuronal satellitosis or extensive grey matter involvement and microcalcifications were considered supportive of a diagnosis of oligodendroglioma. Here, an unspecified change occurred simultaneously with the clinical desire to diagnose oligodendrogliomas because of their chemosensitivity [4, 9, 35]. This shift was followed by a rebounce tightening of criteria which occurred once that non-histological data (1p/19q deletion) showed that the widening histological criteria diluted the percentage of chemo-sensitive tumors [3, 27]. Here, external—molecular—criteria guided a gradual change in histological criteria.

Pathology review within clinical trials

With the knowledge of the significant interobserver variation, the question of how this affects the conduct and interpretation of prospective randomized clinical trials is highly relevant and all too often ignored. One of the first attempts to explore the role of pathology review within a prospective clinical trial on high grade glioma was done within an RTOG study [28]. This study noted a high degree of concordance in locally diagnosed GBM cases (96%), but in only 66% of astrocytomas with anaplastic foci (AAF). Locally diagnosed AAF that were reclassified as GBM had a GBM like survival, whereas locally diagnosed GBM cases that were reclassified as AAF had an in-between survival. This is noteworthy, as apparently the initial local diagnosis of a GBM did make a difference in outcome. It suggests that the initial diagnosis of AAF picked out a subgroup that had a better outcome, despite the central review diagnosis of GBM. The authors showed that the misclassification they observed would seriously affect the power of a clinical study on AAF, assuming that the investigational treatment does improve outcome in AAF but not in GBM. Some confirmation of that assumption comes from an EORTC study on AA [14]. That study failed to show an improvement of adjuvant chemotherapy, but similar to the RTOG study a high level of histological disconcordance was noted. At central pathology review, over half (53%) of the locally diagnosed AA cases could not be confirmed. Of note, a second reviewer disagreed frequently with the first reviewer but a sensitivity analysis of the study based on confirmed AA by either of the two central pathologists showed an improved outcome after adjuvant chemotherapy compared to treatment with radiotherapy alone (EORTC, data on file). Similarly, a large randomized study on grade II glioma confirmed the presence of a low grade glioma in 74% of patients of whom material was available for review [33]. Since today’s trials are focused on specific tumor types and grades, differences between pathologists have to be addressed in the design and interpretation of these studies in particular on grade II and grade III tumors.

Two recent trials have studied the impact of (neo)adjuvant PCV chemotherapy in anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AOD) and AOA. The rationale of both studies was the observed high response rates to PCV chemotherapy of recurrent anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors, which was at the time of study start still understood as related to oligodendroglial morphology [4, 35]. This was subsequently associated with combined 1p/19q loss [6]. For both trials, both pure and mixed anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors were eligible, and they required either two or three anaplastic features to be present as part of the inclusion criteria [5, 34]. Mixed tumors were allowed in both trials provided 25% of oligodendroglial elements were present. One trial—conducted by the RTOG in North America—required central confirmation of the diagnosis prior to study inclusion, the other—European—EORTC trial had central pathology review after the inclusion. Both trials showed that (neo)adjuvant PCV improves progression-free survival but not overall survival. In both trials, results of pathology review of included patients have been published.

In the EORTC trial on 368 patients, the diagnosis of a grade III oligodendroglial tumor was confirmed in 257 patients out of 348 with material available for review (74%) [15]. The EORTC trial has been used to study the interobserver variation of the pathology diagnosis. Using a review panel, 114 cases were classified by 9 independent pathologists [17]. Review diagnoses ranged from low grade astrocytoma to GBM. The panel reached a consensus on 52% of AOD and in only 8% of the AOA, and survival was clearly associated with the diagnosis at review. Molecular analysis in the dataset of the EORTC study demonstrated combined 1p/19q loss in only 26% of the cases with sufficient material available for analysis, and in considerable percentages of patients molecular lesions usually associated with GBM were found (e.g. EGFR amplification in 51 out of 233 samples) [15]. Clearly, this trial suffered from a more heterogeneous patient population than intended, with many patients harboring glioblastoma-like tumors and only a minority of the patients having the chemotherapy sensitivity-associated 1p/19q co-deletion.

A different route was taken in the RTOG trial 94-02. Here, pathology review was conducted prior to study entry, although unfortunately it is unclear how many patients were rejected from the trial because of discordant pathology diagnoses at central review. The percentage of patients with tumor with 1p/19q loss in this study was considerably higher as compared to the EORTC study (93 of 201 cases; 46%). In this study, a second pathology review study has been conducted after the first central review to confirm the patient’s eligibility resulting in an enriched for oligodendroglioma patient population. For that study, all available samples were reviewed by two new and independent reviewers and in case of disagreement by a third reviewer [11]. The authors scored the samples for the presence or absence of “classical for oligodendroglioma (CFO), including cellular monomorphism, round/regular nuclei, presence of nodules, microcalcifications, microcysts, and chickenwire vasculature”. CFO tumors were highly associated with 1p/19q loss (present in 80%; as opposed to only 13% of non-CFO). The authors concluded that central pathology review is an important component to establish uniformity of entry criteria in future trials. Moreover, in CFO, a trend toward increased survival after neoadjuvant PCV was present. Nonetheless, the κ score between the two expert pathologists was only 0.55, indicative of a moderate amount of interobserver agreement. One of the experts did not classify 25 as CFO out of 115 cases that were considered CFO at the end of the review process. Moreover, despite the central pathology review at study entry confirming the oligodendroglial nature of the tumor (and thus all cases were diagnosed as oligodendroglioma by two pathologists), the reviewers that took part in the second review still diagnosed some tumors as AA or GBM.

A German study on anaplastic glioma (regardless of lineage) compared initial treatment with chemotherapy versus initial treatment with radiotherapy [38]. Similar to the RTOG study, central confirmation of the histological diagnosis was required prior to study entry. The investigators noted a high concordance between the local and the central diagnosis (κ = 0.7). Remarkably, they also noted a similar survival in AOA and AOD, in which sense this trial is unique: virtually all studies on this topic have shown a better survival in AOD as compared to AOA [11, 15, 22]. This suggests that despite the good concordance the results may differ from those obtained in other countries. Some indications what may have played a role here are only touched upon by the authors in the discussion part of the manuscript. Here, it is mentioned that a rather restrictive central histologic AOA classification was used: cases of astrocytic tumors with just minute or ambiguous oligodendroglial differentiation features did not qualify for the diagnosis of AOA. It thus appears that the criteria for mixed oligoastrocytomas were narrowed. In fact, older studies have already shown the interobserver variation in the diagnosis of mixed oligoastrocytoma [18]. If the border between AOA and AA is shifted toward a more oligodendroglial phenotype, stage migration (also known as the Will Rogers phenomenon) occurs and it is no longer a surprise the survival of AOA becomes similar to that of AOD [10]. Indeed, the blunt statement in the abstract that AOD and AOA share the same better prognosis than AA is in fact illustrative of the different set of criteria used and indicative of the role of interobserver variation and of stage migration.

What is the explanation of the consistent presence of interobserver variation?

Some of the interobserver variations appear simply due to technicalities: not reviewing exactly the same material may result in a different diagnosis because of sample differences. This may especially be an issue in cases in which only very tiny fragments or a few slides are submitted for the review process (sample error). As an example, cases have been observed where the submission of more material resulted in a different diagnosis. More fundamental is however the way tumors are classified. Several subtypes of glioma exist, which are currently distinguished by their morphological appearance. The standard for brain tumor classification, the WHO classification, uses morphological descriptions for the various histologies and grades which contain subjective elements, with terms such as ‘moderately increased’ cellularity for grade II astrocytoma, and ‘increased cellularity’ for AA [19]. For the outsider, the descriptions contain elements of circular reasoning: oligodendroglioma is “composed of neoplastic cells morphologically resembling oligodendroglia …” [25]. Because of these definitions, boundaries between grades and tumor types are subject to interpretation, and pathology remains an art rather than fully evidence-based science. Perhaps more importantly, the dedifferentiation of low grade tumors into more high grade tumors is a gradual and continuous process, and as a result the boundaries between grades are artificial: tumor grades are not reflecting true and existing different entities.

Would molecular diagnostics improve the situation?

The current concept behind WHO classification into grade I–IV tumors is that it reflects overall outcome. The phenotype of a tumor is the result of the genotype and the influence of the tumor’s environment on the tumor. One would expect that molecular diagnostics will contribute to a better classification of brain tumors. As an example, a recent study conducted at our department on 60 patients with recurrent astrocytoma treated with temozolomide showed three cases with combined 1p/19q loss (Taal et al., submitted). All were confirmed astrocytomas at central review, all three had a complete response to temozolomide which is a treatment outcome one would expect in 1p/19q co-deleted oligodendroglioma. The class of mixed oligoastrocytomas is a clear example of the difficulties of glioma histology. This diagnosis is by definition the result of the presence of a group of tumors that have both astrocytic and oligodendroglial elements. It has long been clear however that at the molecular level these tumors usually show either 1p/19q co-deletion suggestive of an oligodendroglial tumor, or TP53 mutations suggestive of astrocytic lineage [20]. The WHO 2007 has dealt to some extent with this category of mixed tumors, by removing the AOAs with necrosis from the anaplastic glioma to the grade IV tumors. That leaves unanswered whether there is any rationale to label these tumors glioblastoma with oligodendroglial features, although survival of this group may be slightly better [15, 21]. However, this remains a mixed bag of tumors, difficult to sort out with morphological criteria alone.

Indeed, the results of studies on systemic molecular analysis are beginning to allow the identification of tumors at a more fundamental level, and have increased our understanding of some aspects of the clinical behavior of these tumors. In particular, 1p/19q loss, TP53 mutations, IDH1 mutations, EGFR amplification, PTEN mutations are now believed to characterize specific subsets of tumors, related to grade and lineage of various glial tumors. The above-mentioned example showed that astrocytic tumors with 1p/19q co-deletion may respond similarly to chemotherapy as one would expect from oligodendroglial tumors, providing a rationale for molecular entry criteria as opposed to histological entry criteria.

If molecular analysis is used for the classification of glioma, the next question would be which type of molecular analysis would be used for that and whether histology continues to play a decisive role in that process. In several studies, it has been shown that molecular classification based on gene expression analysis provided a more accurate predictor of survival than histology [13, 23, 29]. In one of these studies on 276 gliomas, molecularly defined clusters contained a wide variety of histologies and grades, and vice versa the various histologies and grades ended in different clusters [13]. Within the GBM, gene expression arrays allowed the identification of several genes that correlate with subclasses of GBM with different outcome and perhaps different outcome to treatment [8]. Although a molecularly based classification of glioma is an attractive idea, many questions still remain unanswered. As an example, the reviewers of RTOG trial noted that histologically defined ‘classical for oligodendroglioma tumors’ may actually benefit from PCV chemotherapy, which could not be demonstrated for 1p/19q loss. Indeed, clustering analysis of gene expression analysis of a large set of glioma showed that several of non-1p/19q co-deleted tumors clustered with 1p/19q co-deleted tumors and some GBM clustered with pilocytic tumors [13]. More likely, a combined histological and molecular approach will improve outcome.

Also, the current WHO classification of brain tumors and the treatment decisions based on it are the results of years of clinical research. Any new classification has to prove itself in a prospective study that demonstrates the new classification is better correlated with survival and—preferably—improves the outcome. Such an effort could be limited to a subset of tumors undergoing a specific treatment: any molecular criterion that predicts outcome of a subgroup of glioma to a specific treatment would be a major leap forward. Current large cooperative group trials are using molecular entry criteria (especially 1p/19q status and MGMT promoter methylation). Analysis of the results—and unfortunately the maturation of these trials may take years—will tell if these entry criteria provide a step forwards. Of note, before molecular criteria are accepted, a similar process of assessment of interlaboratory variation should be conducted. Results from MGMT promoter methylation studies have shown methylation rates varying from 20 to 66%, most likely resulting from differences in laboratories [7, 32]. As long as science is the objective of these assays, this is no major concern, but such differences are intolerable if the assays are used for the clinical management of patients.

Pathology review and conclusions derived from clinical trials

Although the conclusion from the above presented data on interobserver variation appears to be that central pathology review should be mandatory prior to patient inclusion in clinical trials on glioma, that does not cover all the aspects of the problem. Intuitively, it may appear to make sense to include patients only after central review of the diagnosis as this will result in a more reliable and homogeneous population. However, it does not necessarily imply that a more ‘correct’ population is included. In the absence of a gold standard, this diagnosis remains an art. It does ensure, however, a more homogenous patient population, but even here issues are present. There are very little data on intraobserver variation, but it seems reasonable to assume that it will be less than the variation present between different observers. Nonetheless, even after central mandatory review at baseline of a trial, the problem still exists at the next level. Should any new treatment result in a better survival in a specific tumor type or grade as demonstrated in a clinical trial with central histology confirmation prior to randomization, it will still be the local pathologists who assign tumor type and grade to the patient: day to day clinical decisions on the management of these patients will continue to be guided by the local pathologists. In other words, the results of a trial for which patients were only eligible after central review will only be ‘true’ for the patients diagnosed with a specific condition by the specific central pathologists of that study, and cannot be automatically generalized to patients diagnosed with that condition by other pathologists. This issue is on the question of external validation or generalizability of the results of a trial, an often ignored element of clinical trials [26]. That question addresses whether the results of a trial can be reasonably applied to a group of patients diagnosed with that condition in a particular setting in routine clinical practice. Restrictive inclusion criteria and local policies of centers participating in a trial that result in only a subset of patients with a given diagnosis entering a particular trial limit the external validity of that trial. In the way, the trial is reported some of these can be addressed, from the pathology perspective one minimal requirement ought to be that the number of patients rejected because of non-confirmed histology is reported [31].

The opposite reasoning is that entering patients into a trial based on the local diagnosis reflects a more ‘real life scenario’, or every day’s clinical practice. However, it needs to be realized that the question whether the conclusion of a trial on a specific subtype can be generalized to all patients locally diagnosed with that tumor also holds for a trial in which patients were entered based on the local diagnosis. After such a trial, any local center will have the same issues when trying to define its own patients in comparison to the reported general study population. In fact, because of the likely increased heterogeneity of included tumors, the amount of uncertainty about the actual histologies included in the trial will be larger.

Clinical perspective

For clinicians, it is important to realize the limitations of the pathological diagnosis of glioma. Most importantly, they should understand that pathological diagnoses are not carved in stone and are subject to interobserver variation. Also, they should realize that glioma grades are not to be understood as distinct biological entities. That implies that the clinical information including the scan details should be considered when making treatment plans, and in case of issues the opinion of another pathologist should be asked. For pathologists, it is important to understand that this is not a motion of non-confidence. On a daily basis, they are taking decisions which can be traced down for the years to come which makes their work more difficult and easy to criticize—but that is certainly not the intention of this review.

The psychology of multiple pathologists reviewing cases is complicated in itself. This should be organized in a way that this does not become a process of bargaining and authority. Circulating slides from clinically annotated cases in order to decrease interobserver variation is something that should be considered. This should be organized on an international level, to avoid the development of national standards not shared in other countries. Histology review as part of a clinical trial brings another issue: what if the central review diagnosis considers another diagnosis, which would justify another treatment choice? Or even randomization in another trial? First, it needs to be realized that the central review pathologist as a rule will not have a legal status in the hospital of the treating physician. Then, the central diagnosis in a particular patient is another opinion, not necessarily the correct one. The clinician should try to integrate both opinions into the management of the patient, using other evidence to guide treatment decisions (aspects of MR scans, age of the patient and the like). It may seem a slippery slope, but not having the second opinion (or even ignoring it) does not make it less slippery. And, patients are entitled to be informed of these kinds of disagreements. Which is sometimes difficult to explain, especially if the consequences are big (Table 1).

Conclusion

Interobserver variation in the pathological diagnosis is a well-recognized and major issue in both the management of brain tumor patients and the conduct of clinical trials on brain tumors. Although in trials mandatory pathology review at baseline is likely to result in a more homogeneous patient population, the absence of objective and quantitative criteria for the histological diagnosis implies that even after central review prior to inclusion the entered patients represent merely a sample taken according to the diagnosis of one pathologist. This questions the external validity and generalizability of the trial results. More objective, quantitative and in particular reproducible histological criteria are urgently needed, as patient treatment, trial conduct and trial interpretation depend on the adequate selection of specific treatments for specific patients. If molecular criteria improve the classification of tumors, once validated these should be introduced into the WHO criteria for brain tumors without further delay. Current trials are using molecular entry criteria, but it will take years before results become available. Routine review of the histological diagnosis of glioma by a second pathologist in daily clinical practice should be considered, preferably from an outside institution. Today’s communication technologies are beginning to make this feasible even without the material transfer of tumor specimens.

References

Aldape K, Simmons ML, Davis RL et al (2000) Discrepancies in diagnoses of neuroepithelial neoplasms: the San Francisco Bay Area Adult Glioma Study. Cancer 88:2342–2349

Bruner JM, Inouye L, Fuller GN, Langford LA (1997) Diagnostic discrepancies and their clinical impact in a neuropathology referral practice. Cancer 79:796–803

Burger PC (2002) What is an oligodendroglioma? Brain Pathol 12:257–259

Cairncross G, Macdonald D, Ludwin S et al (1994) Chemotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma. J Clin Oncol 12:2013–2021

Cairncross JG, Berkey B, Shaw E et al (2006) Phase III trial of chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (RT) versus RT alone for pure and mixed anaplastic oligodendroglioma (RTOG 9402): an intergroup trial by the RTOG, NCCTG, SWOG, NCI CTG and ECOG. J Clin Oncol 24:2707–2714

Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC et al (1998) Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 90:1473–1479

Clarke JL, Iwamoto FM, Sul J et al (2009) Randomized phase II trial of chemoradiotherapy followed by either dose-dense or metronomic temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 27:3861–3867

Colman H, Zhang L, Sulman EP et al (2010) A multigene predictor of outcome in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 12:49–57

Coons SW, Johnson PC, Scheithauer BW, Yates AJ, Pearl DK (1997) Improving diagnostic accuracy and interobserver concordance in the classification and grading of primary gliomas. Cancer 79:1381–1391

Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK (1985) The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med 312:1604–1608

Giannini C, Burger PC, Berkey BA et al (2008) Anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors: refining the correlation among histopathology, 1p 19q deletion and clinical outcome in Intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9402. Brain Pathol 18:360–369

Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Weaver A et al (2001) Oligodendrogliomas: reproducibility and prognostic value of histologic diagnosis and grading. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60:248–262

Gravendeel LA, Kouwenhoven MC, Gevaert O et al (2009) Intrinsic gene expression profiles of gliomas are a better predictor of survival than histology. Cancer Res 69:9065–9072

Hildebrand J, Gorlia T, Kros JM et al (2008) Adjuvant dibromodulcitol and BCNU chemotherapy in anaplastic astrocytoma: results of a randomised European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III study (EORTC study 26882). Eur J Cancer 44:1210–1216

Kouwenhoven MC, Gorlia T, Kros JM et al (2009) Molecular analysis of anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors in a prospective randomized study: a report from EORTC study 26951. Neuro-Oncology 11:737–746

Kouwenhoven MC, Kros JM, French PJ et al (2006) 1p/19q loss within oligodendroglioma is predictive for response to first line temozolomide but not to salvage treatment. Eur J Cancer 42:2499–2503

Kros JM, Gorlia T, Kouwenhoven MC et al (2007) Panel review of anaplastic oligodendroglioma from EORTC trial 26951: assessment of consensus in diagnosis, influence of 1p/19q loss and correlations with outcome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66:545–551

Krouwer HGJ, van Duinen SG, Kamphorst W, van der Valk P, Algra A (1997) Oligoastrocytomas: a clinicopathological study of 52 cases. J Neuro-Oncol 33:223–238

WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (2007) Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (eds) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon

Maintz D, Fiedler K, Koopmann J et al (1997) Molecular genetic evidence for subtypes of oligoastrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:1098–1104

McDonald JM, See SJ, Tremont IW et al (2005) The prognostic impact of histology and 1p/19q status in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. Cancer 104:1468–1477

Miller CR, Dunham CP, Scheithauer BW, Perry A (2006) Significance of necrosis in grading of oligodendroglial neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol 24:5419–5426

Nutt CL, Mani DR, Betensky RA et al (2003) Gene expression-based classification of malignant gliomas correlates better with survival than histological classification. Cancer Res 63:1602–1607

Reifenberger G, Kros JM, Burger PC, Louis DN, Collins VP (2000) Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (eds) Pathology and genetics of tumours of the nervous system. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Reifenberger, G, Kros, JM, Louis, DN, Collins, VP. (2007) Oligodendroglioma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (eds) WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. WHO OMS International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Rothwell PM (2005) External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet 365:82–93

Sasaki H, Zlatescu MC, Betensky RA et al (2002) Histopathological-molecular genetic correlations in referral pathologist-diagnosed low-grade “oligodendroglioma”. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61:58–63

Scott CB, Nelson JS, Farnan NC et al (1995) Central pathology review in clinical trials for patients with malignant glioma. Cancer 76:307–313

Shirahata M, Iwao-Koizumi K, Saito S et al (2007) Gene expression-based molecular diagnostic system for malignant gliomas is superior to histological diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res 13:7341–7356

Smith JS, Perry A, Borell TJ et al (2000) Alterations of chromosome arms 1p and 19q as predictors of survival in oligodendrogliomas, astrocytoma, and mixed oligoastrocytomas. J Clin Oncol 18:636–645

Sorg C, Schmidt J, Buchler MW, Edler L, Marten A (2009) Examination of external validity in randomized controlled trials for adjuvant treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 38:542–550

Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Pirker C, Filipits M et al (2010) O6-Methylguanine DNA methyltransferase protein expression in tumor cells predicts outcome of temozolomide therapy in glioblastoma patients. Neuro-Oncology 12:28–36

van den Bent MJ, Afra D, De Witte O et al (2005) Long term results of EORTC study 22845: a randomized trial on the efficacy of early versus delayed radiation therapy of low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in the adult. Lancet 366:985–990

van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Brandes AA et al (2006) Adjuvant PCV improves progression free survival but not overall survival in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas: a randomized EORTC phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 24:2715–2722

van den Bent MJ, Kros JM, Heimans JJ et al (1998) Response rate and prognostic factors of recurrent oligodendroglioma treated with procarbazine, CCNU and vincristine chemotherapy. Neurology 51:1140–1145

van den Bent MJ, Looijenga LHJ, Langenberg K et al (2003) Chromosomal anomalies in oligodendroglial tumors are correlated with clinical features. Cancer 97:1276–1284

von Deimling, A, Reifenberger, G, Kros, JM, Louis, DN, Collins, VP. (2008) Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (eds) WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Wick W, Hartmann C, Engel C et al (2009) NOA-04 randomized phase III trial of sequential radiochemotherapy of anaplastic glioma with procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine or temozolomide. J Clin Oncol 27:5874–5880

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Bent, M.J. Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: a clinician’s perspective. Acta Neuropathol 120, 297–304 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-010-0725-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-010-0725-7