Abstract

A systematic review of references conducted in the process of developing the Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis did not find many high-quality research reports. There were no criteria for diagnosis, severity assessment, or patient transfer, and no established principles of clinical practice guidelines for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. In order to develop guidelines that would be useful in clinical practice, an understanding of the current status of clinical practice for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis was considered essential. After several open symposia and a survey of these two diseases, we developed and published a Japanese-language version of Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis. In order to prepare international Guidelines, we had repeated discussions about the draft Guidelines together with international experts, and, following the Consensus Meeting, held on April 1–2, 2006, in Tokyo, with the attendance of 300 world experts in the field, the International Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis were developed. In this article, we outline the comments and opinions given at the International Meeting and how they are reflected in the final version of the Guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Guidelines should not only be based on evidence but should also meet the needs of current medical practice. We thought that adequate discussion, to receive feed-back at open symposia and conferences, was essential during the development of the Guidelines.

As one of the Integrated Research Projects for Assessing Medical Technology, sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, a Research Group for the Preparation and Diffusion of Guidelines for the Management of Acute Biliary Tract Infection was established. With support from the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, development of the Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis has been underway since 2003.

After several open consensus conferences and open symposia to obtain feedback from members of these societies, a Japanese-language version of “Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis” was prepared and published.

An English-language version of these Guidelines (draft) was discussed, via e-mail, with worldwide experts on acute cholangitis and cholecystitis, with the aim of publishing International Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis. Much spirited debate, which changed many areas of diagnosis criteria, severity assessment, etc, then took place at the International Consensus Meeting, held in Tokyo on April 1 and 2, 2006, attended by experts from Japan and many other parts of the world. After several modifications by the Organizing Committee, the final version is published here as the International Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis.

In this article, we outlined comments and opinions given at the International Consensus Meeting, and how they are reflected in final version of the Guidelines.

Changes made in the Guidelines at the International Consensus Meeting for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis (Tokyo, April 1–2, 2006)

In order to prepare international guidelines based on the “Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis”, draft guidelines were modified several times by the Organizing Committee, and discussion was carried out, via email, with worldwide experts on acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis before the International Consensus Meeting.

The discussions were followed by the 2-day International Consensus Meeting, held in Tokyo on April 1–2, 2006, with the attendance of about 300 world experts specializing in acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis, in order to prepare evidence-based guidelines. Attendees from abroad are listed (Page 8–10). Discussions at the Meeting are outlined below.

Diagnostic criteria for acute cholangitis

Some panelists proposed that “History of biliary disease” should be included in the diagnostic criteria for acute cholangitis (Table 1B). A history of biliary disease, such as gallstones, a history of previous biliary surgery, and having an indwelling biliary stent play an important role in making the diagnosis, as agreed upon by many participants at the Consensus Meeting. But other panelists disagreed and proposed different criteria (Table 1C).

Because not only an increase but also a decrease in the WBC count indicates inflammation, “leukocytosis” was changed to “abnormal WBC count”. Because Creactive protein (CRP) is sometimes not elevated, “or other evidence of inflammatory response” was added. “WBC count” and “elevation of CRP level or other evidence of inflammatory response” are separate items.

As aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) sometimes increase in acute cholangitis, “abnormal liver function tests, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Γ-GTP, AST, ALT)” was added.

Imaging findings of inflammatory changes in acute cholangitis are also useful for diagnosis. “Biliary dilatation or etiology (stricture, tumor, stones)” (Table 1A) was changed to “biliary dilatation, inflammatory findings, or etiology (stricture, tumor, stones)” (Table 1B, C).

Two ways of making a definite diagnosis were proposed; in revision 1 (Table 1B), these were: (1) three or four items in A (Charcot’s triad) and (2) any item in A + two items in B + C, and in Revision 2 (Table 1C), these were: Any item in A + two items in B + C.

As more than 90% of the participants at the Tokyo Consensus Meeting agreed on four criteria in revision 1 (Table 1B), a history of biliary disease was included, and abnormal WBC count and elevation of CRP or other evidence of inflammatory response were included in the final version of the diagnostic criteria for acute cholangitis (Table 1D).

In Table 1D, two or more items in A were defined as a suspected diagnosis, and either: (1) Charcot’s triad (items 2 + 3 + 4 in A) or (2) two or more items in A plus both items in B + C, were defined as a definite diagnosis of acute cholangitis.

Severity assessment criteria for acute cholangitis (Table 2)

More than 70% of the participants at the Tokyo Consensus Meeting agreed that the severity of acute cholangitis should be divided into three grades, severe (grade III), moderate (grade II), and mild (grade I). To stratify acute cholangitis into three grades, two different criteria were necessary, and it was decided to use “onset of organ dysfunction” and “response to the initial medical treatment” as criteria for the severity assessment of acute cholangitis.

“Severe (grade III)” acute cholangitis was defined as that associated with any one of the categories of organ/system dysfunction or severe local inflammation listed in Table 2. This was supported by more than 90% of the panelists at the International Consensus Meeting. But the thresholds of these categories were not discussed at the Summary session.

There was some argument about whether the score on an acute physiology scoring system, such as acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II, or a multiple organ dysfunction scoring system, such as Marshall’s system or the sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) system should be used as a criterion for severe (grade III) acute cholangitis. The principal advantage of these scoring systems is that they provide gradations of severity. The APACHE II system has been validated, especially for critical care patients, including patients with sepsis, and acute cholangitis can be interpreted as a subset of sepsis. The disadvantage of these scoring systems is that the scores are sometimes troublesome to calculate, and critically speaking, they have not been satisfactory validated in patients with acute cholangitis. The vote on this argument showed that 37.8% of the panelists supported the use of APACHE II and 62.2% did not. As a result of this vote, the chairmen of this session, Drs. Yoshifumi Kawarada (Japan) and Henry Pitt (United States), had proposed to remit the final decision of whether or not APACHE II should be included as a criterion for severe (grade III) acute cholangitis to the Organizing Committee, and this proposal was approved by the audience.

Neither “recurrent symptom” nor “malignancy as etiology” always shows moderate (grade II) acute cholangitis. Therefore, both of these were deleted from the criteria for “moderate (grade II)” acute cholangitis. The thresholds of high fever and WBC counts were not decided.

After the International Meeting, all the criteria and thresholds of severity of acute cholangitis were discussed and decided or by the Organizing Committee (Table 2B). The definition of moderate (grade II) acute cholangitis was changed to: “acute cholangitis that does not respond to the initial medical treatment and is not associated with organ dysfunction (Table 2B).

Diagnostic criteria for acute cholecystitis (Table 3)

After the discussion during the Tokyo International Consensus Meeting, almost unanimous agreement was achieved (Table 3B). However, 19% of the panelists from abroad expressed the necessity for minor modifications, because the diagnostic criteria did not include technetium hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (Tc-HIDA) scans as an item in the provisional version.

Some panelists insisted that “suspected diagnosis” was not necessary, and that only “definite diagnosis” should be included in the diagnostic criteria for acute cholecystitis. There was no discussion on whether, if “suspected diagnosis” was deleted, how the definition of definite diagnosis should be modified.

After the International Meeting, “A. Local signs of inflammation”; “B. Systemic signs of inflammation” and “C. Imaging findings” were clearly specified in the diagnostic criteria for acute cholecystitis (Table 3B). Tc-HIDA scan was included in “C. Imaging findings”. “Suspected diagnosis” was deleted from the criteria.

Severity assessment criteria for acute cholecystitis (Table 4)

Before the International Meeting, “Severe (grade III)” acute cholecystitis was defined as that associated with dysfunction in any one of the organs/systems or any one of the severe local inflammation categories listed in Table 4A.

At the Meeting, concepts of the severity of acute cholecystitis were discussed and changed as shown below. The concept of the final version of the severity assessment of acute cholecystitis, “severe (grade III)” acute cholecystitis was defined as that associated with organ dysfunction, “moderate (grade II)” acute cholecystitis was defined as that associated with difficulty to perform cholecystectomy due to local inflammation, and “mild (grade I)” acute cholecystitis was defined as that which does not meet the criteria of “severe” or “moderate” acute cholecystitis.

In the severity assessment initially proposed at the Meeting “moderate (grade II)” acute cholecystitis was associated with any of the following conditions: (1) abnormal WBC (>15 000, >18 000? threshold was not decided), (2) palpable inflammatory mass, (3) onset more than 72–96 h and (4) Serious wall thickening and fluid collection around the gallbladder.

Some panelists insisted that “serious” should be changed to “thickening” or deleted. Whether threshold of wall thickening should be included was not discussed. If included, the extent of the thickness, whether 6–7 mm or 8 mm, or twice that of the normal gallbladder wall, also remained as questions. Also, it was queried whether both the thickness of the gallbladder wall and fluid collection around the gallbladder were necessary for the diagnosis of moderate acute cholecystitis?

Panelists suggested that liver cirrhosis should be described in a Note.

After the International Meeting, each item and its threshold were discussed and decided on by the Organizing Committee. “Severe local inflammation” was deleted from the criteria for severe (grade III) acute cholecystitis (Table 4B). “Onset more than 72–96 h” was changed to “prolonged local signs of inflammation” in the criteria for moderate (grade II) acute cholangitis.

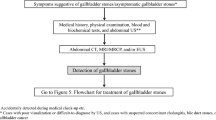

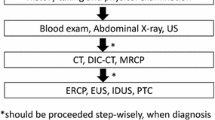

Flowcharts

Flow charts for the management of acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis according to severity were also discussed and modified at the Meeting.

Almost all panelists agreed with the flowchart for “General guidance for the management of acute biliary infection” (Fig. 1). But in the flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis (Fig. 2a), panelists suggested that medical treatment should be begun before assessment of the severity of acute cholangitis. Therefore, the flowchart was changed, as shown in Fig. 2b.

In the flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis (Fig. 3a), because the concept of severity of cholecystitis was changed, this flowchart was also modi-fied (Fig. 3b). As “severe (grade III)” acute cholecystitis is associated with organ dysfunction, urgent/early drainage was preferred to urgent/early cholecystectomy for “severe (grade III)” cholecystitis. Similarly, as “moderate (grade II)” acute cholecystitis is associated with difficulty to perform cholecystectomy due to local inflammation, urgent/early drainage was preferred to early/elective cholecystectomy for “moderate (grade II)” cholecystitis also.

Definitions of severity: mild to severe (grades I–III)

Before the Meeting, the severity of both acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis was classified as mild, moderate, and severe. But, with these criteria, even “moderate” acute cholangitis and “moderate” acute cholecystitis sometimes cause organ failure and even death. This definition could have confused users of these Guidelines, as “moderate” diseases are usually regarded as those having a good course without high morbidity or mortality. Therefore, instead of using the categories “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe”, the categories “grades I, II, and III” were used as the severity classifications for both acute cholangitis and acute cholecystitis.

Conclusion

In the preparation of the Guidelines for Acute Biliary Tract Infections (Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis), we found that there was not a sufficient volume of high-quality research. In this article, we have reported the process of developing the Guidelines, ranging from the identification of current clinical practice for acute biliary tract infection, to the proposals for the Guidelines and the improvements based on consensus. The Guidelines are the world’s first international guidelines for the clinical management of acute biliary tract infections (acute cholangitis and cholecystitis), and it is strongly expected that they may be used broadly in everyday medical practice throughout the world as Guidelines that fully reflect local and regional conditions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, who provided us with great support and guidance in the preparation of the Guidelines. This process was conducted as part of the Project on the Preparation and Diffusion of Guidelines for the Management of Acute Cholangitis (H-15-Medicine-30), with a research subsidy for fiscal 2003 and 2004 (Integrated Research Project for Assessing Medical Technology) sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

We also truly appreciate the panelists who cooperated with and contributed significantly to the International Consensus Meeting, held in Tokyo on April 1 and 2, 2006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

About this article

Cite this article

Mayumi, T., Takada, T., Kawarada, Y. et al. Results of the Tokyo Consensus Meeting Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14, 114–121 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-006-1163-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-006-1163-8