Abstract

Human hearing and balance impairments are often attributable to the death of sensory hair cells in the inner ear. These cells are hypersensitive to death induced by noise exposure, aging, and some therapeutic drugs. Two major classes of ototoxic drugs are the aminoglycoside antibiotics and the antineoplastic agent cisplatin. Exposure to these drugs leads to hair cell death that is mediated by the activation of specific apoptotic proteins, including caspases. The induction of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in response to cellular stress is a ubiquitous and highly conserved response that can significantly inhibit apoptosis in some systems by inhibiting apoptotic proteins. Induction of HSPs occurs in hair cells in response to a variety of stimuli. Given that HSPs can directly inhibit apoptosis, we hypothesized that heat shock may inhibit apoptosis in hair cells exposed to ototoxic drugs. To test this hypothesis, we developed a method for inducing HSP expression in the adult mouse utricle in vitro. In vitro heat shock reliably produces a robust up-regulation of HSP-70 mRNA and protein, as well as more modest up-regulation of HSP-90 and HSP-27. The heat shock does not result in death of hair cells. Heat shock has a significant protective effect against both aminoglycoside- and cisplatin-induced hair cell death in the utricle preparation in vitro. These data indicate that heat shock can inhibit ototoxic drug-induced hair cell death, and that the utricle preparation can be used to examine the molecular mechanism(s) underlying this protective effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing loss is the most common sensory impairment in humans and the sixth most common chronic health condition in the United States (Adams et al. 1999). Hearing loss is often caused by death of sensory hair cells in the inner ear. Hair cells are sensitive to death from a variety of stresses such as aging, noise trauma, genetic disorders, and exposure to certain therapeutic drugs. Ototoxic drugs include the aminoglycoside antibiotics and the antineoplastic agent cisplatin. Studies in several laboratories over the past few years have revealed considerable new information regarding the mechanisms underlying ototoxic drug-induced hair cell death. Ototoxic hair cell death has been characterized as apoptotic by both morphologic and molecular studies (Li et al. 1995; Lang and Liu 1997; Vago et al. 1998; Forge and Li 2000; Cunningham et al. 2002; Matsui et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2003; Matsui et al. 2003). Both cisplatin- and aminoglycoside-induced hair cell death are significantly inhibited by broad-spectrum inhibition of caspases (Liu et al. 1998; Cunningham et al. 2002; Matsui et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2003; Matsui et al. 2003; Shimizu et al. 2003). Aminoglycoside-induced hair cell death is significantly inhibited by inhibition of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNKs), also known as “stress-activated protein kinases” (SAPKs) (Pirvola et al. 2000; Ylikoski et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2003; Matsui et al. 2004; Matsui et al. 2004). JNKs belong to the family of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases that also includes extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and p38.

Heat shock protein induction is a ubiquitous stress response

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are part of an evolutionarily conserved stress response that is activated by changes in the cellular environment. Activation of HSPs is the most ubiquitous and highly conserved stress response in biology (Martindale and Holbrook 2002). HSPs are found in bacteria, yeast, plants, and all other eukaryotes. The HSP family includes both constitutive and stress-activated members. In unstressed cells, HSPs have constitutive functions that are important for protein trafficking, folding, and metabolism. Stress-induced HSP expression occurs in response to a variety of stressors such as hyperthermia, ischemia, and environmental toxicants.

According to their molecular weights, HSPs are classified as: (1) HSP-90 proteins, which support the cytoskeleton and chaperone steroid hormone receptors; (2) HSP-70 proteins, which are the most highly conserved and the most stress-inducible HSPs in mammals; (3) small HSPs, which include ubiquitin and HSP-27 that are produced in response to ischemia.

Stress-induced HSP expression promotes cellular survival in a large number of systems. One well-characterized HSP inducer is heat stress. Heating an entire animal induces most HSPs and protects cells against a number of stresses. For example, short-term total-body hyperthermia has been shown to protect the retina against light-induced damage and to prevent ischemia-induced death in both cardiomyocytes and hippocampal neurons (Barbe et al. 1988; Chopp et al. 1989; Marber et al. 1995; Radford et al. 1996; Plumier et al. 1997; Yenari et al. 1998). HSP-70 is induced in the inner ear in response to heat shock, cochlear ischemia, cisplatin exposure, and noise trauma (Dechesne et al. 1992; Myers et al. 1992; Thompson and Neely 1992; Lim et al. 1993; Oh et al. 2000). In mice, total body heat stress is effective at preventing hearing loss caused by exposure to excessive noise (Yoshida et al. 1999). Local heat stress can inhibit both cochlear hair cell death and hearing loss following noise trauma (Sugahara et al. 2003). However, there are no data available regarding the effects of heat shock on ototoxic drug-induced hair cell death. We examined the role of heat shock in mediating survival and death of sensory hair cells exposed to ototoxic drugs.

Methods

Animals

Adult CBA/J mice (4–6 weeks of age) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and housed in the central animal care facility at the Medical University of South Carolina. Mice were euthanized by overdose of Nembutal (Abbott Laboratories, USA). All animal use and care procedures were approved by the MUSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Utricle cultures

Utricles from adult mice were dissected under sterile conditions and cultured free-floating (4–8 utricles/well) in 24-well tissue culture plates as previously described (Cunningham et al. 2002). Culture medium consisted of 2:1 (v/v) basal medium Eagle (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with Earle's balanced salt solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), and 50 U/ml penicillin G (Sigma). Neomycin sulfate solution (Sigma) was added to the culture medium at final concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 5.0 mM. Cisplatin was supplied as a 1 mg/ml stock solution (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH, USA) and diluted into culture medium at final concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 25.0 μg/ml. Neither neomycin nor cisplatin was added to control cultures. Utricles were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air environment.

Heat shock protocol

For heat shock experiments, utricles were cultured overnight at 37°C in control media as described above. Utricles were then transferred (with all of the surrounding media) into sterile 1.5-ml microfuge tubes. Tubes containing utricles to be heat shocked were placed into a 43°C water bath for 30 min. At the end of the heat shock period, utricles and media were transferred back to the tissue culture plate, which was replaced in the 37°C incubator for an additional 2–30 h. Control (no heat shock) utricles were transferred to a microfuge tube for 30 min, but were maintained at 37°C.

Hair cell counts

For hair cell counts, cultured utricles were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and prepared for whole-mount, double-label fluorescent immunohistochemistry using antibodies against calmodulin and calbindin as previously described (Cunningham et al. 2002). Otoconia were removed from fixed utricles by a stream of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) applied via a syringe. Utricles were incubated in blocking solution (2% bovine serum albumin/0.8% normal goat serum/0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 3 h at room temperature (RT). Utricles were double-labeled by using a monoclonal antibody against calmodulin (Sigma) and a polyclonal antibody against calbindin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Utricles were incubated overnight at 4°C in both primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution (calmodulin, 1:150; calbindin, 1:250). Utricles were washed in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated for 3 h at RT in secondary antibodies diluted in blocking solution as follows: Alexa 488 conjugated goat antimouse IgG (1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA); Alexa 594 conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:500, Molecular Probes). Utricles were washed and whole-mounted in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA) and coverslipped.

The double-label immunohistochemistry protocol allows for separate counts of hair cells in the two distinct regions of the mouse utricle: anticalmodulin labels the cell bodies (and some stereocilia bundles) of all hair cells in the utricle, and anticalbindin labels only the cell bodies of the striolar hair cells (Dechesne et al. 1988; Ogata and Slepecky 1998; Cunningham et al. 2002). Double-labeled (calmodulin-positive and calbindin-positive) hair cells were counted as “striolar,” and calmodulin-positive/calbindin-negative hair cells were counted as “extrastriolar.” This definition of the striolar region likely includes the narrow band of hair cells in the juxtastriola region (Leonard and Kevetter 2002; Desai et al. 2005).

Using a high-resolution monochrome digital camera (Zeiss Axiocam MR) and imaging software (Zeiss AxioVision), hair cells were counted in each of eight (four striolar and four extrastriolar) 900-μm2 areas. Using the software, boxes were drawn that were 30 μm on a side. These boxes were placed over the image of the utricle such that the four striolar boxes were approximately evenly spaced along the length of the striolar region. The four extrastriolar boxes were placed such that two of them were in the lateral extrastriolar area, and the other two were in the medial extrastriolar region (Desai et al. 2005). Hair cell density is reported as the mean number (average of four boxes) of hair cells (striolar or extrastriolar) per unit area for each utricle. Striolar hair cells have been shown to be more sensitive than extrastriolar hair cells to aminoglycoside-induced death (Cunningham et al. 2002).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

For real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) experiments, control and heat-shocked utricles were collected at 2 and 6 h after heat shock and stored in RNAlater RNA Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The 2- and 6-h timepoints were selected based on literature indicating that HSP expression peaks 2–6 h after heat shock (Yoshida et al. 1999; Simpson et al. 2004). Utricles were homogenized, and total RNA was collected (RNAEasy, Qiagen). RNA was reverse-transcribed (TaqMan, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the resulting cDNA was used for SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) real-time PCR amplification of HSP-70, HSP-90, and HSP-27. Primer sets were as follows: HSP-70 forward primer (Yoshida et al. 1999): 5′-AGGCCAGGGCTGGTATTACT-3′; HSP-70 reverse primer: 5′-AATGACCCGAGTTCAGGATG-3′, yielding a 170-bp PCR product. HSP-90 forward primer: 5′-GTGCGTGTTCATTCAGCCAC-3′; HSP-90 reverse primer: 5′-GCAATTTCTGCCTGAAAGGC-3′, yielding a 100-bp product. HSP-27 forward primer: 5′-GAGAACCGAACGACCGTCC-3′; HSP-27 reverse primer: 5′-CCCAATCCTTTGACCTAACGC-3′, yielding a 100-bp product. For all RT-PCR experiments, 18S ribosomal RNA was amplified as an internal control by using the following primers: 18S forward primer 5′-TTCGGAACTGAGGCCATGATT-3′; 18S reverse: 5′-TTTCGCTCTGGTCCGTCTTG-3′, yielding a 100-bp product (Yoshida et al. 1999).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical detection of HSPs, utricles were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at the end of the culture period. Immunohistochemical procedures were performed as described above, except that the primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-HSP-70 (diluted 1:200, SPA-810; Stressgen Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA, USA); anti-HSP-90 (diluted 1:100, #4874; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); Anti-HSP-27 (diluted 1:75, #06-517; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA). All HSP immunochemistry was detected by using Alexa 488 conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:500, Molecular Probes). Hair cell stereocilia were labeled by using Alexa 594 conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes).

Results

Cisplatin exposure results in dose-dependent death of hair cells in the utricle preparation

We previously published the dose–response relationship between neomycin concentration and hair cell survival (Cunningham et al. 2002). However, the relationship between cisplatin dose and hair cell survival had not been examined in this preparation. Utricles were cultured for 24 h in the presence of varying concentrations of cisplatin. At the end of the culture period, utricles were fixed and hair cells were counted. Results are shown in Figure 1. Cisplatin exposure resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in hair cell survival [one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05]. Based on these data, further experiments with cisplatin were performed using the 20 μg/ml dose.

Cisplatin dose–response relationship. Utricles were cultured for 24 h in various concentrations of cisplatin. Hair cells were double-labeled and counted using calmodulin and calbindin immunofluorescence (see Methods). For both the striolar and extrastriolar regions, hair cell survival decreases as cisplatin concentration increases (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). For the extrastriolar region, Tukey's multiple comparison correction showed that the 25 μg/ml dose was statistically different from 0, 10, and 15 μg/ml at the 0.05 level of significance. Likewise, 20 μg/ml was statistically different from 0 μg/ml. For the striolar region, only the 25 μg/ml dose was different from 0 μg/ml at the 0.05 level of significance. Shown are mean hair cell numbers ± SEM for n = 5–7 utricles per concentration.

Development of the heat shock protocol

In pilot experiments, we examined the effects of various temperatures and durations of heat shock, based on protocols found in the literature (Poe and O'Neill 1997; Braiden et al. 2000; Ju and Tseng 2004; Simpson et al. 2004). We found that exposure to temperatures above 44°C for periods as short as 10 min resulted in a significant loss of hair cells (data not shown). Likewise, if the duration of heat shock (at any temperature above 41°C) was as long as 1 h, we consistently observed loss of hair cells. Exposure to temperatures below 42°C or heat shocks with durations of less than 15 min did not result in any loss of hair cells, but these exposure conditions also did not result in any measurable heat shock response (i.e., up-regulation of HSP-70 mRNA or protein). We found that heat shock at 43°C for 30 min reliably produces a robust up-regulation of HSP-70 mRNA and protein, but does not result in death of hair cells. This heat shock protocol (43°C for 30 min) was used for all of the experiments reported here.

Heat shock results in robust up-regulation of HSP-70 MRNA and protein

HSP-70 mRNA and protein levels were examined in heat-shocked and control utricles. Utricles were cultured at 37°C overnight. Utricles then either remained at 37°C (control) or were heat shocked at 43°C for 30 min. Heat-shocked and control utricles were then cultured at 37°C for an additional 2 or 6 h. Quantitative SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR was used to examine HSP-70 mRNA levels in heat-shocked and control utricles. At the end of each PCR cycle, the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system measures SYBR Green fluorescence that is proportional to the amount of double-stranded DNA generated by the PCR. Results indicate that heat-stressed utricles demonstrate a 256-fold increase in HSP-70 mRNA (relative to control utricles) 2 h after heat shock (Fig. 2A). HSP-70 mRNA levels remain elevated at 90-fold higher than controls 6 h after heat shock (Fig. 2A).

Heat shock results in robust upregulation of HSP-70. (A) SYBR Green real-time RT-PCR results for HSP-70 mRNA in heat-shocked and control utricles. For each sample, C t is defined as the number of thermocycles required for the SYBR Green fluorescence intensity to reach a threshold (0.1, indicated above by horizontal line) above background. HSP-70 mRNA levels are highest at 2 h after heat shock (C t = 22.1 ± 0.06). HSP-70 mRNA levels remain high at 6 h after heat shock (C t = 23.3 ± 0.01). C t for control utricles is 30.1 ± 0.20. Assuming that the amount of PCR product doubles with every cycle, these data indicate a 256-fold difference in HSP-70 mRNA between control and heat-shocked utricles at 2 h after heat shock. Each experimental condition was run in duplicate, and data are shown for both of the duplicate samples. (B, C) HSP-70 immunoreactivity increases in hair cells after heat shock. Control and heat-shocked utricles were labeled by using phalloidin (red) and anti-HSP-70 (green). Control utricles show little HSP-70 immunoreactivity (B). HSP-70 immunoreactivity is significantly increased 6 h after heat shock (C).

To confirm that the increase in HSP-70 MRNA was indicative of an increase in HSP-70 protein levels, we examined control and heat-shocked utricles via fluorescent immunohistochemistry. Utricles were cultured and heat shocked as described above. At 6 h after heat shock, utricles were fixed and processed for indirect immunohistochemistry by using a monoclonal antibody directed against human HSP-70. Results indicate a low level of HSP-70 expression in control utricles (Fig. 2B) and robust up-regulation of HSP-70 protein levels in hair cell bodies of heat-shocked utricles (Fig. 2C). These data demonstrate that the heat shock protocol results in significant induction of HSP-70 protein.

Heat shock results in up-regulation of HSP-90 and HSP-27 mRNA levels

To more fully characterize the cellular response to heat shock, we examined the levels of two other significant HSPs, HSP-90 and HSP-27. Quantitative RT-PCR results demonstrate that at 2 h after heat shock, HSP-90 mRNA had increased approximately 9-fold (Fig. 3A). HSP-90 mRNA levels continued to increase over the next few hours. At 6 h post-heat shock, HSP-90 mRNA had increased to approximately 18-fold above control levels (Fig. 3A). Immunohistochemical data confirmed that HSP-90 was up-regulated in hair cells 6 h after heat shock (Figs. 3B, C).

Heat shock results in upregulation of HSP-90. (A) Real-time RT-PCR for HSP-90 mRNA. HSP-90 mRNA levels increase 9.31-fold relative to controls by 2 h after heat shock [C t (controls) = 28.6 cycles; C t (2 h post-heat shock) = 25.4 cycles]. HSP-90 mRNA levels had further increased to 18.8-fold over controls by 6 h after heat shock [C t (6 h) = 24.4 cycles]. (B, C) HSP-90 immunoreactivity increases in hair cells after heat shock. Control and heat-shocked utricles were labeled using phalloidin (red) and anti-HSP-90 (green). Control utricles show baseline levels of HSP-90 immunoreactivity (B). At 6 h after heat shock, HSP-90 immunoreactivity is increased in hair cells relative to controls (C).

Real-time RT-PCR data indicated a more moderate up-regulation of HSP-27 mRNA (Fig. 4A). Two hours after heat shock, HSP-27 mRNA levels were up 7.7-fold relative to control values. By 6 h post-heat shock, HSP-27 mRNA levels had begun to decrease, and were only at 3.3-fold above control levels. This up-regulation was not obvious in immunohistochemical data obtained 6 h after heat shock (Figs. 4B, C).

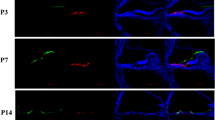

Heat shock results in up-regulation of HSP-27 mRNA. (A) Real-time RT-PCR for HSP-27 mRNA. Two hours after heat shock, HSP-27 mRNA levels are increased 7.7-fold relative to controls [C t (controls) = 27.3 cycles; C t (2 h after heat shock) = 24.3]. By 6 h after heat shock, HSP-27 levels have decreased again to 3.3-fold above controls [C t (6 h post-heat shock) = 25.6 cycles]. (B, C) HSP-27 immunoreactivity in control and heat-shocked utricles. Utricles were labeled by using phalloidin (red) and anti-HSP-27 (green). HSP-27 immunofluorescence appears similar for control (B) and heat-shocked (C) utricles.

Heat shock inhibits neomycin-induced hair cell death

To determine whether heat shock treatment has an effect on ototoxic hair cell death, we exposed both control and heat-shocked utricles to a moderate dose of neomycin (1 mM) for 24 h. Four groups of utricles were prepared: (1) no heat shock, no neomycin; (2) heat shocked, no neomycin; (3) no heat shock, neomycin-exposed; (4) heat shocked, neomycin-exposed. Six hours after the heat shock, utricles in groups 3 and 4 were transferred into wells containing media with 1 mM neomycin. All utricles were cultured for an additional 24 h. At the end of the culture period, utricles were fixed and hair cells were counted. Results are shown in Figure 5. Relative to control utricles, the heat shock treatment alone did not result in loss of hair cells (Figs. 5A, B). In contrast, the neomycin treatment alone resulted in significant loss of hair cells (Fig. 5C). Heat shock treatment significantly inhibited neomycin-induced hair cell death in both the striolar and extrastriolar regions (Figs. 5D, E; two-way ANOVA, p < 0.05 for each region). Specifically, heat shock treatment prevented approximately 60% of the hair cell death caused by neomycin exposure in both regions of the utricle. These data indicate that heat shock treatment has a protective effect against neomycin-induced hair cell death.

Heat shock inhibits neomycin-induced hair cell death. Utricles were cultured at 37°C overnight. Two groups of utricles were then heat-shocked at 43°C for 30 min. Six hours after heat shock, one group of control utricles and one group of heat-shocked utricles were exposed to 1 mM neomycin for 24 h. Utricles were fixed and double-labeled for calmodulin and calbindin immunoreactivity, and hair cells were counted. (A) Control (no neomycin, no heat shock) utricles show normal numbers of striolar (red, calbindin +) and extrastriolar (green, calmodulin +) hair cells. (B) Heat-shocked (no neomycin) utricles appear similar to control utricles. (C) Neomycin-treated (no heat shock) utricles show significant hair cell loss, especially in the striolar region. (D) Heat-shocked, neomycin-treated utricles show decreased hair cell death relative to neomycin alone. (E) Quantification of hair cell densities in each condition. Heat shock treatment significantly inhibited neomycin-induced hair cell death in both the striolar and extrastriolar regions. Shown are mean ± SEM hair cell densities for n = 7–13 utricles per condition. Asterisks indicate significance (ANOVA, p < 0.05; Tukey's multiple comparison correction) relative to neomycin alone.

Heat shock inhibits cisplatin-induced hair cell death

The heat shock treatment also had a significant effect on the survival of hair cells exposed to cisplatin. In an experiment with the same design as the neomycin experiment shown above in Figure 5, we exposed both control and heat-shocked utricles to a moderate dose of cisplatin (20 μg/ml) for 24 h. Six hours after the heat shock, utricles were fixed and hair cells counted. Results are shown in Figure 6. The heat shock treatment had a significant protective effect against cisplatin-induced hair cell death in the extrastriolar region (at this dose of cisplatin, we did not observe a significant decrease in hair cell density in the striolar region). These data indicate that heat shock has a significant protective effect against cisplatin-induced hair cell death in the extrastriolar region (ANOVA, p < 0.001).

Heat shock inhibits cisplatin-induced hair cell death. Six hours after heat shock, one group of control utricles and one group of heat-shocked utricles were exposed to 20 μg/ml cisplatin for 24 h. Heat shock treatment inhibited the hair cell death caused by exposure to cisplatin in the extrastriolar region. This protective effect of heat shock against cisplatin-induced hair cell death in the extrastriolar region is significant. There were no significant differences in the striolar region. Shown are mean ± SEM hair cell densities for n = 9–12 utricles per condition. Asterisk indicates significance (ANOVA, p < 0.001; Tukey's multiple comparison correction) relative to cisplatin alone.

Discussion

The cisplatin dose–response relationship in both the striolar and extrastriolar regions indicates that hair cell density decreases as cisplatin concentration increases. Interestingly, we saw less hair cell loss in the striolar region with cisplatin than in the extrastriolar region. These data are in contrast with our data on aminoglycoside-induced hair cell death, which indicate that striolar hair cells are more susceptible than extrastriolar hair cells to death caused by exposure to neomycin (Cunningham et al. 2002).

In vitro heat shock resulted in robust up-regulation of HSP-70 mRNA levels of greater than 250-fold. These data are consistent with in vivo data on total body heat stress in mice, which resulted in a transient increase of 104-fold in HSP-70 mRNA levels in whole cochleas (Yoshida et al. 1999). In addition, immunohistochemical data confirmed that HSP-70 protein levels increased following heat shock, and that this increase occurred in hair cells. The increase in HSP-70 did not appear to be limited to hair cells, however, because HSP-70 immunofluorescence was also visible in deeper cell layers of the utricle. Thus, the heat shock likely results in up-regulation of HSP-70 in both hair cells and supporting cells. Because all of the HSP immunochemistry was all performed in whole mount using phalloidin as the hair cell marker, we were not able to determine whether HSP staining was different in the striolar vs. the extrastriolar region. However, immunofluorescence for each of the HSP antibodies appeared to be evenly distributed across the sensory epithelium, with no obvious or consistent regional differences in staining intensity.

Heat shock resulted in more moderate increases in mRNA levels of both HSP-90 and HSP-27. HSP-90 mRNA levels were elevated approximately 9-fold relative to controls at 2 h after the heat shock. HSP-90 mRNA levels continued to increase to approximately 18-fold above control levels 6 h after heat shock. In contrast, HSP-27 mRNA levels showed a shorter time course of elevation, rising to approximately 8-fold above controls at 2 h, but falling again to only 3-fold above controls by 6 h after the heat shock. This difference in the time courses of HSP elevation suggests that mRNA levels of HSP-90 and HSP-27 are differentially regulated in response to heat shock. In addition, the immunohistochemical data on HSP-27 suggest that the increase in HSP-27 mRNA may not result in a comparable increase in HSP-27 protein levels. However, the absence of an obvious increase in HSP-27 immunofluorescence may merely reflect the fact that immunofluorescent data are not as quantitative as real-time RT-PCR data. In addition, HSP-27 function can be regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranslational levels. Heat shock can result in phosphorylation of HSP-27 by MAPKAP kinase 2, possibly resulting in changes in its stability or function (Landry et al. 1992; Rouse et al. 1994).

The most significant finding of this study is that heat shock significantly inhibits both neomycin- and cisplatin-induced hair cell death. The most straightforward explanation of this result is that the protective effect of heat shock against ototoxic drug-induced hair cell death is the result of HSP-mediated inhibition of specific apoptotic signaling pathways. Studies in other systems have demonstrated that HSPs can inhibit the apoptotic machinery by interfering with some of the same events that have been shown to be important in mediating ototoxic drug-induced hair cell apoptosis, including cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and phosphorylation of JNK.

Heat shock proteins can inhibit the apoptotic machinery by interfering with apoptosome assembly at a number of sites. For example, HSP-70 can inhibit the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria (Tsuchiya et al. 2003). Further downstream, both HSP-70 and HSP-90 can prevent apoptosome assembly by inhibiting cytoplasmic cytochrome c from binding to Apaf-1 (Beere et al. 2000; Li et al. 2000; Pandey et al. 2000; Saleh et al. 2000). HSP-27 can bind directly to cytochrome c to prevent apoptosome assembly (Bruey et al. 2000). Even in the presence of an activated apoptosome, HSP-70 can prevent death of cells in which caspases are activated, indicating that HSPs may be able to inhibit the cell death machinery farther downstream than any other known antiapoptotic protein (Jaattela et al. 1998). Interestingly, our data indicate that the magnitude of the protective effect of heat shock against neomycin-induced hair cell death is very similar to that we obtained by using a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor (z-VAD) (Cunningham et al. 2002).

Heat shock proteins can also inhibit JNK-mediated apoptosis. In human acute lymphoblastic leukemia T cells with tetracycline-inducible HSP-70 expression, hyperthermia-induced JNK activation was inhibited by HSP-70 induction (Mosser et al. 1997). In cells that constitutively overexpress HSP-70, heat-induced apoptosis was blocked (Mosser et al. 1997). The inhibitory effect of HSP-70 on JNK activation appears to be through HSP-70-mediated stimulation of dephosphorylation (inactivation) of JNK (Meriin et al. 1999). In healthy cells, JNK is rapidly dephosphorylated. The rate of JNK dephosphorylation is reduced by protein-damaging stimuli such as oxidative stress. Elevation of HSP-70 levels inhibits this reduction in JNK dephosphorylation, effectively keeping JNK inactive (Meriin et al. 1999).

Although it seems reasonable to hypothesize that the protective effect of heat shock is mediated by HSP induction, it is also possible that proteins other than HSPs contribute to the heat shock response. In fact, it seems likely that the heat shock results in activation of a number of stress-inducible proteins. For example, superoxide dismutase (SOD) can be activated by heat shock (Moriyama-Gonda et al. 2002). In addition, SOD-1 knockout mice show increased susceptibility to both noise-induced hearing loss and age-related hair cell death (McFadden et al. 1999a,b; Ohlemiller et al. 1999). Thus, the mechanism of the protective effect may involve multiple classes of proteins. The notion that the protective effect of heat shock is mediated by HSP induction is supported by data indicating that geranylgeranylacetone (GGA), an inducer of the heat shock factor 1 (HSF-1) transcription factor, inhibits gentamicin-induced hair cell death (Takumida and Anniko 2005). Finally, in addition to directly inhibiting apoptotic mechanisms, HSPs play critical roles in cellular homeostasis via their chaperone functions. Thus, the mechanism of heat shock-induced inhibition of ototoxic hair cell death may be via HSP-mediated repair or degradation of misfolded proteins (Sreedhar and Csermely 2004). Experiments are currently underway in our laboratory to examine the molecular mechanism(s) of the protective effect of heat shock against both aminoglycoside- and cisplatin-induced hair cell death. Elucidating the molecular interactions underlying this important intrinsic protective mechanism will enhance our understanding of the regulation of hair cell death and survival. In addition, understanding these interactions in detail may provide insights for the design of therapies aimed at preventing or reversing hearing loss.

References

Adams P, Hendershot G, Marano M. (1999) Current Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1996. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD.

Barbe MF, Tytell M, Gower DJ, Welch WJ. Hyperthermia protects against light damage in the rat retina. Science 241:1817–1820, 1988.

Beere HM, Wolf BB, Cain K, Mosser DD, Mahboubi A, Kuwana T, Tailor P, Morimoto RI, Cohen GM, Green DR. Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:469–475, 2000.

Braiden V, Ohtsuru A, Kawashita Y, Miki F, Sawada T, Ito M, Cao Y, Kaneda Y, Koji T, Yamashita S. Eradication of breast cancer xenografts by hyperthermic suicide gene therapy under the control of the heat shock protein promoter. Hum. Gene. Ther. 11:2453–2463, 2000.

Bruey JM, Ducasse C, Bonniaud P, Ravagnan L, Susin SA, Diaz-Latoud C, Gurbuxani S, Arrigo AP, Kroemer G, Solary E, Garrido C. Hsp27 negatively regulates cell death by interacting with cytochrome c. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:645–652, 2000.

Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, Rubel EW. Hair cell death in the avian basilar papilla: characterization of the in vitro model and caspase activation. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 4:91–105, 2003.

Chopp M, Chen H, Ho KL, Dereski MO, Brown E, Hetzel FW, Welch KM. Transient hyperthermia protects against subsequent forebrain ischemic cell damage in the rat. Neurology 39:1396–1398, 1989.

Cunningham LL, Cheng AG, Rubel EW. Caspase activation in hair cells of the mouse utricle exposed to neomycin. J. Neurosci. 22:8532–8540, 2002.

Dechesne CJ, Thomasset M, Brehier A, Sans A. Calbindin (CaBP 28 kDa) localization in the peripheral vestibular system of various vertebrates. Hear Res. 33:273–278, 1988.

Dechesne CJ, Kim HN, Nowak TS Jr., Wenthold RJ. Expression of heat shock protein, HSP72, in the guinea pig and rat cochlea after hyperthermia: immunochemical and in situ hybridization analysis. Hear Res. 59:195–204, 1992.

Desai SS, Zeh C, Lysakowski A. Comparative morphology of rodent vestibular periphery. I. Saccular and utricular maculae. J. Neurophysiol. 93:251–266, 2005.

Forge A, Li L. Apoptotic death of hair cells in mammalian vestibular sensory epithelia. Hear Res. 139:97–115, 2000.

Jaattela M, Wissing D, Kokholm K, Kallunki T, Egeblad M. Hsp70 exerts its anti-apoptotic function downstream of caspase-3-like proteases. EMBO J. 17:6124–6134, 1998.

Ju JC, Tseng JK. Nuclear and cytoskeletal alterations of in vitro matured porcine oocytes under hyperthermia. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 68:125–133, 2004.

Landry J, Lambert H, Zhou M, Lavoie JN, Hickey E, Weber LA, Anderson CW. Human HSP27 is phosphorylated at serines 78 and 82 by heat shock and mitogen-activated kinases that recognize the same amino acid motif as S6 kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 267:794–803, 1992.

Lang H, Liu C. Apoptosis and hair cell degeneration in the vestibular sensory epithelia of the guinea pig following a gentamicin insult. Hear Res. 111:177–184, 1997.

Leonard RB, Kevetter GA. Molecular probes of the vestibular nerve. I. Peripheral termination patterns of calretinin, calbindin and peripherin containing fibers. Brain Res. 928:8–17, 2002.

Li L, Nevill G, Forge A. Two modes of hair cell loss from the vestibular sensory epithelia of the guinea pig inner ear. J. Comp. Neurol. 355:405–417, 1995.

Li CY, Lee JS, Ko YG, Kim JI, Seo JS. Heat shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis downstream of cytochrome c release and upstream of caspase-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25665–25671, 2000.

Lim HH, Jenkins OH, Myers MW, Miller JM, Altschuler RA. Detection of HSP 72 synthesis after acoustic overstimulation in rat cochlea. Hear Res. 69:146–150, 1993.

Liu W, Staecker H, Stupak H, Malgrange B, Lefebvre P, Van De Water TR. Caspase inhibitors prevent cisplatin-induced apoptosis of auditory sensory cells. NeuroReport 9:2609–2614, 1998.

Marber MS, Mestril R, Chi SH, Sayen MR, Yellon DM, Dillmann WH. Overexpression of the rat inducible 70-kD heat stress protein in a transgenic mouse increases the resistance of the heart to ischemic injury. J. Clin. Invest. 95:1446–1456, 1995.

Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J. Cell Physiol. 192:1–15, 2002.

Matsui JI, Ogilvie JM, Warchol ME. Inhibition of caspases prevents ototoxic and ongoing hair cell death. J. Neurosci. 22:1218–1227, 2002.

Matsui JI, Haque A, Huss D, Messana EP, Alosi JA, Roberson DW, Cotanche DA, Dickman JD, Warchol ME. Caspase inhibitors promote vestibular hair cell survival and function after aminoglycoside treatment in vivo. J Neurosci 23:6111–6122, 2003.

Matsui JI, Gale JE, Warchol ME. Critical signaling events during the aminoglycoside-induced death of sensory hair cells in vitro. J. Neurobiol. 61:250–266, 2004.

McFadden SL, Ding D, Burkard RF, Jiang H, Reaume AG, Flood DG, Salvi RJ. Cu/Zn SOD deficiency potentiates hearing loss and cochlear pathology in aged 129,CD-1 mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 413:101–112, 1999a.

McFadden SL, Ding D, Reaume AG, Flood DG, Salvi RJ. Age-related cochlear hair cell loss is enhanced in mice lacking copper/zinc superoxide dismutase. Neurobiol. Aging 20:1–8, 1999b.

Meriin AB, Yaglom JA, Gabai VL, Zon L, Ganiatsas S, Mosser DD, Sherman MY. Protein-damaging stresses activate c-Jun N-terminal kinase via inhibition of its dephosphorylation: a novel pathway controlled by HSP72. Mol. Cell Biol. 19:2547–2555, 1999.

Moriyama-Gonda N, Igawa M, Shiina H, Urakami S, Shigeno K, Terashima M. Modulation of heat-induced cell death in PC-3 prostate cancer cells by the antioxidant inhibitor diethyldithiocarbamate. BJU Int. 90:317–325, 2002.

Mosser DD, Caron AW, Bourget L, Denis-Larose C, Massie B. Role of the human heat shock protein hsp70 in protection against stress-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 17:5317–5327, 1997.

Myers MW, Quirk WS, Rizk SS, Miller JM, Altschuler RA. Expression of the major mammalian stress protein in the rat cochlea following transient ischemia. Laryngoscope 102:981–987, 1992.

Ogata Y, Slepecky NB. Immunocytochemical localization of calmodulin in the vestibular end-organs of the gerbil. J. Vestib. Res. 8:209–216, 1998.

Oh SH, Yu WS, Song BH, Lim D, Koo JW, Chang SO, Kim CS. Expression of heat shock protein 72 in rat cochlea with cisplatin-induced acute ototoxicity. Acta Otolaryngol. 120:146–150, 2000.

Ohlemiller KK, McFadden SL, Ding DL, Flood DG, Reaume AG, Hoffman EK, Scott RW, Wright JS, Putcha GV, Salvi RJ. Targeted deletion of the cytosolic Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase gene (Sod1) increases susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss. Audiol. Neurootol. 4:237–246, 1999.

Pandey P, Saleh A, Nakazawa A, Kumar S, Srinivasula SM, Kumar V, Weichselbaum R, Nalin C, Alnemri ES, Kufe D, Kharbanda S. Negative regulation of cytochrome c-mediated oligomerization of Apaf-1 and activation of procaspase-9 by heat shock protein 90. EMBO J. 19:4310–4322, 2000.

Pirvola U, Xing-Qun L, Virkkala J, Saarma M, Murakata C, Camoratto AM, Walton KM, Ylikoski J. Rescue of hearing, auditory hair cells, and neurons by CEP-1347/KT7515, an inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. J. Neurosci. 20:43–50, 2000.

Plumier JC, Krueger AM, Currie RW, Kontoyiannis D, Kollias G, Pagoulatos GN. Transgenic mice expressing the human inducible Hsp70 have hippocampal neurons resistant to ischemic injury. Cell Stress Chaperones 2:162–167, 1997.

Poe BS, O'Neill KL. Inhibition of protein synthesis sensitizes thermotolerant cells to heat shock induced apoptosis. Apoptosis 2:510–517, 1997.

Radford NB, Fina M, Benjamin IJ, Moreadith RW, Graves KH, Zhao P, Gavva S, Wiethoff A, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, Williams RS. Cardioprotective effects of 70-kDa heat shock protein in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93:2339–2342, 1996.

Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, Morange M, Alonso-Llamazares A, Zamanillo D, Hunt T, Nebreda AR. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell 78:1027–1037, 1994.

Saleh A, Srinivasula SM, Balkir L, Robbins PD, Alnemri ES. Negative regulation of the Apaf-1 apoptosome by Hsp-70. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:476–483, 2000.

Shimizu A, Takumida M, Anniko M, Suzuki M. Calpain and caspase inhibitors protect vestibular sensory cells from gentamicin ototoxicity. Acta Otolaryngol. 123:459–465, 2003.

Simpson SA, Alexander DJ, Reed CJ. Heat shock protein 70 in the rat nasal cavity: localisation and response to hyperthermia. Arch. Toxicol. 78:344–350, 2004.

Sreedhar AS, Csermely P. Heat shock proteins in the regulation of apoptosis: new strategies in tumor therapy: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 101:227–257, 2004.

Sugahara K, Inouye S, Izu H, Katoh Y, Katsuki K, Takemoto T, Shimogori H, Yamashita H, Nakai A. Heat shock transcription factor HSF1 is required for survival of sensory hair cells against acoustic overexposure. Hear Res. 182:88–96, 2003.

Takumida M, Anniko M. Heat shock protein 70 delays gentamicin-induced vestibular hair cell death. Acta Otolaryngol. 125:23–28, 2005.

Thompson AM, Neely JG. Induction of heat shock protein in interdental cells by hyperthermia. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 107:769–774, 1992.

Tsuchiya D, Hong S, Matsumori Y, Shiina H, Kayama T, Swanson RA, Dillman WH, Liu J, Panter SS, Weinstein PR. Overexpression of rat heat shock protein 70 is associated with reduction of early mitochondrial cytochrome C release and subsequent DNA fragmentation after permanent focal ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23:718–727, 2003.

Vago P, Humbert G, Lenoir M. Amikacin intoxication induces apoptosis and cell proliferation in rat organ of Corti. NeuroReport 9:431–436, 1998.

Wang J, Van De Water TR, Bonny C, de Ribaupierre F, Puel JL, Zine A. A peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase protects against both aminoglycoside and acoustic trauma-induced auditory hair cell death and hearing loss. J. Neurosci. 23:8596–8607, 2003.

Yenari MA, Fink SL, Sun GH, Chang LK, Patel MK, Kunis DM, Onley D, Ho DY, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Gene therapy with HSP72 is neuroprotective in rat models of stroke and epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 44:584–591, 1998.

Ylikoski J, Xing-Qun L, Virkkala J, Pirvola U. Blockade of c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway attenuates gentamicin-induced cochlear and vestibular hair cell death. Hear Res. 163:71–81, 2002.

Yoshida N, Kristiansen A, Liberman MC. Heat stress and protection from permanent acoustic injury in mice. J. Neurosci. 19:10116–10124, 1999.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH DC07613-01, NIH/NCRR extramural research facilities construction (C06) grants C06 RR015455 and C06 RR14516 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources, and an MUSC University Research Committee Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cunningham, L.L., Brandon, C.S. Heat Shock Inhibits both Aminoglycoside- and Cisplatin-Induced Sensory Hair Cell Death. JARO 7, 299–307 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-006-0043-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-006-0043-x