Abstract

We examined the interconnectedness of stigma experiences in families living with HIV, from the perspective of multiple family members. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 33 families (33 parents with HIV, 27 children under age 18, 19 adult children, and 15 caregivers). Parents were drawn from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study, a representative sample of people in care for HIV in US. All of the families recounted experiences with stigma, including 100% of mothers, 88% of fathers, 52% of children, 79% of adult children, and 60% of caregivers. About 97% of families described discrimination fears, 79% of families experienced actual discrimination, and 10% of uninfected family members experienced stigma from association with the parent with HIV. Interpersonal discrimination seemed to stem from fears of contagion. Findings indicate a need for interventions to reduce HIV stigma in the general public and to help families cope with stigma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HIV-related stigma is prevalent in US (Gostin & Weber, 1998; Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2002) and has a profound influence on the adjustment of people with HIV (PWH) and their families. PWH have reported numerous mental and physical effects from stigma, including fear, isolation, anxiety, depression, and poor psychological functioning (Barroso & Powell-Cope, 2000; Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001; Clark, Lindner, Armistead, & Austin, 2003; Courtenay-Quirk, Wolitski, Parsons, & Gomez, 2006; Kang, Rapkin, Remien, Mellins, & Oh, 2005; Relf, 2005; Sowell et al., 1997; Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006). For example, HIV-infected mothers who report high levels of HIV-related stigma score significantly lower on measures of physical, psychological, and social functioning, and higher on measures of depression, compared to mothers who report low levels of HIV-related stigma (Murphy, Austin, & Greenwell, in press). Stigma experienced by close associates of PWH has similarly been shown to result in poor mental health outcomes (Barroso & Powell-Cope, 2000; Donenberg & Pao, 2005; Murphy, Roberts, Hoffman, Molina, & Lu, 2003; Reyland, Higgins-D’Alessandro, & McMahon, 2002), including worse psychosocial adjustment and greater delinquent behavior among children with HIV-infected parents (Forehand et al., 1998; Murphy et al., in press), and greater caregiver burden and depression (Demi, Bakeman, Moneyham, Sowell, & Seals, 1997). However, no research to date has investigated the interconnectedness of HIV stigma experiences from the perspective of multiple family members, including how prejudice and discrimination against HIV-infected parents, their caregivers, and their children can have dynamic effects on all members of the family unit. Families may be vulnerable to a unique form of HIV stigma, due to misconceptions that parents with HIV are exposing their own and others’ children to infection (Lekas, Siegel, & Schrimshaw, 2006).

As conceptualized by Goffman (1963), stigma occurs when negative meanings that are attached to a discrediting trait, such as HIV/AIDS, result in avoidance, less than full acceptance, and discrimination of people with that trait. The three primary forms of HIV stigma that have been identified in the research literature–felt, enacted, and courtesy stigma–are important for understanding the dynamics of PWH and their families. Felt stigma is the fear of being discriminated against (Scambler, 1998). The process of stigmatization culminates in enacted stigma, or prejudicial attitudes and actual discriminatory behaviors such as interpersonal avoidance, verbal insults, and violence (Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen, & Phelan, 2001; Scambler, 1989). Enacted stigma can also be exhibited in the form of structural discrimination from institutions such as health care or housing discrimination. Courtesy stigma, the least studied of the three types of stigma, refers to prejudice and discrimination against individuals who are associated with stigmatized others (Goffman, 1963; Hebl & Mannix, 2003). In addition to affecting family members and friends, the negative consequences of courtesy stigma may extend to those who are merely seen in the presence of a stigmatized other (Hebl & Mannix, 2003). Even children as young as 7–14 years of age are aware of courtesy stigma related to parental HIV, and such awareness affects their decisions to disclose parents’ serostatus to friends (Murphy, Roberts, & Hoffman, 2002).

Most research on HIV stigma and families has been qualitative. Nearly all of this qualitative research has explored HIV stigma from the standpoint of parents with HIV, with a primary focus on mothers (Antle, Wells, Goldie, DeMatteo, & King, 2001; Barroso & Powell-Cope, 2000; Brackis-Cott, Mellins, Abrams, Reval, & Dolezal, 2003; DeMatteo, Wells, Salter Goldie, & King, 2002; Hackl, Somlai, Kelly, & Kalichman, 1997; Ingram & Hutchinson, 1999, 2000; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Scrimshaw & Siegel, 2002; Semple et al., 1993; Vallerand, Hough, Pittiglio, & Marvicsin, 2005; Wiener, Battles, & Heilman, 1998). Some studies have also collected data from children with HIV-infected parents (Antle et al., 2001; Armistead et al., 1999; Brackis-Cott et al., 2003; Reyland et al., 2002; Vallerand et al., 2005; Wiener et al., 1998) or caregivers, including mothers, grandmothers, partners, other family members, and friends (DeMatteo et al., 2002; Poindexter & Linsk, 1999; Powell-Cope & Brown, 1992). However, prior research has not explored HIV-stigma issues from the perspective of all family members, including HIV-infected fathers and mothers, and their children and caregivers.

Most qualitative analyses of data from parents living with HIV and their family members have documented the presence of both enacted and felt stigma. For example, in qualitative interviews, PWH have reported experiences with interpersonal and structural discrimination that include being isolated and forced to move, and being denied admission to school and daycare for their children (Gielen, O’Camp, & Faden, 1997; Ingram and Hutchinson, 1999); women with HIV have faced condemnation about their decision to have children, given the risk of infection for the child (Ingram & Hutchinson, 2000; Lekas et al., 2006). A recurring theme in the realm of felt stigma, across both qualitative and quantitative research, has been parental worry about children experiencing discrimination (Corona et al., 2006; DeMatteo et al., 2002; Ingram & Hutchinson, 1999; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Scrimshaw & Siegel, 2002; Semple et al., 1993; Vallerand et al., 2005). Such fear of courtesy stigma has often been used as a reason for nondisclosure to children, due to a belief that children would disclose to others and consequently experience discrimination. Nevertheless, research has rarely uncovered instances of courtesy stigma against family members of an HIV-infected individual. For example, in two studies of caregivers, courtesy stigma was uncommon relative to felt stigma, possibly because caregivers rarely disclosed children’s or partners’ HIV (Poindexter & Linsk, 1999; Powell-Cope & Brown, 1992). Courtesy stigma, when experienced, has included social isolation, rejection, and avoidance by friends, as well as employment and housing discrimination.

In sum, prior qualitative research has described enacted and felt stigma among parents with HIV and, to a lesser extent, courtesy stigma against family members of PWH. A complete qualitative analysis that links multiple forms of stigma that are perceived by multiple family members is critical for understanding the range of ways in which different types of stigma affect families living with HIV. Specific information about the types of HIV stigma experienced by families could be used, for example, to design interventions to help PWH and their families cope with and manage stigmatization.

In the present study, we conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with parents living with HIV/AIDS, as well as their children and caregivers, in order to explore experiences with, and the interconnectedness of, stigma in a family context. We examined parents’ narratives for experiences with felt and enacted stigma; children’s and caregivers’ narratives for experiences with felt and courtesy stigma; and the linkages among family members’ stigma accounts. In addition, HIV stigma may be exhibited differently, depending on the status of other social categories to which the target belongs (Parker & Aggleton, 2003; Reidpath & Chan, 2005). Thus, we examined whether PWH and their families who were people of color, women, men who have sex with men (MSM), or injection drug users experienced compounded stigma burden from their HIV and other devalued social categories. Participants were drawn from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS), a representative sample of people receiving care for HIV in the US.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

Between March 2004 and March 2005, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a subsample from HCSUS, a national probability sample of people at least 18 years old with known HIV infection who made at least one visit to a medical provider in the contiguous US during January–February 1996 (Frankel, Shapiro, & Duan, 1999; Schuster et al., 2000; Shapiro, Berk, & Berry, 1999). HCSUS participants were eligible for the present study if they participated in the third wave (of three waves) of HCSUS in 1997–1998 and the HCSUS Risk and Prevention survey in 1997–1998 (Chen, Philips, Kanouse, Collins, & Miu, 2001); if they had at least one child younger than 23 years old on March 1, 2004; and if they lived with or had seen at least one of their children in the past month at the time they were contacted for participation in the present study. Because of budgetary limitations, we restricted ourselves to a stratified random subsample of 522 (54%) of the 975 eligible participants, sampling all families with a child under 18 and favoring participants in the HCSUS follow-up database among the remainder.

We interviewed selected HCSUS participants, their children (9–17 years old), their adult children (≥18 years old), and a caregiver who provided additional support or cared for the HIV-infected parent and/or a child or children in the family. Caregivers provided additional information about how the child was affected by the parent’s illness. Children were eligible to be interviewed if they knew about their parent’s HIV status and had lived with or seen their parent in the past month. Two nieces were interviewed as adult children because they lived with and considered the target parents to be parental figures. Parents consented for minor children, and minor children gave their assent for study participation. The project received institutional review board approval from both RAND and UCLA.

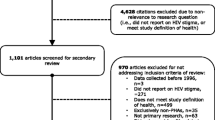

We were able to make contact with 146 of 522 (28%) target parents using the most current phone number or address available in HCSUS records or through looking up current contact information in Lexis-Nexis. Eighty-eight were ineligible (60%), 22 were active refusals (15%), 3 were passive refusals (3%), and 33 (22%) agreed to participate. For the 33 families in which the target parent participated, we interviewed 27 children, 19 adult children, and 15 caregivers.

Measures

Socio-demographic Variables

Parents’ age, gender, race/ethnicity, annual household income, education, HIV transmission/exposure group, and HIV diagnosis year were obtained from baseline (1995) HCSUS data and linked to the semi-structured interview data. Household composition; geographic region; and child, adult child, and caregiver age and gender were obtained during the semi-structured interview.

Interview Protocol

Interview questions were open-ended and broad in order to elicit a detailed description of family members’ experiences, including: questions to parents about disclosure to children and about disclosure to others; questions to children regarding fears about others finding out about parents’ HIV, about disclosure to others, and about their perceptions of parents’ infectiousness; and questions to caregivers about disclosure to children and about infectiousness. The interview protocol did not include direct questions about stigma. However, family members discussed stigma spontaneously, most commonly in response to interview questions on disclosure of HIV and fears about HIV transmission—two topics that have been intertwined with stigma issues in prior qualitative and quantitative work (Barroso & Powell-Cope, 2000; Brackis-Cott et al., 2003; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006; Lee & Rotheram-Borus, 2002; Reyland et al., 2002; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b; Vallerand et al., 2005; Vanable et al., 2006). Examination of spontaneous utterances in participants’ qualitative narratives has been used to study stigma among PWH (Lekas et al., 2006) and can reveal the dimensions of participants’ experiences in their usual context (Wood, 1996).

Adults were interviewed first and asked whether their child was aware of their HIV status; if so, parents were asked to consent for the child to be interviewed. Children were screened to ensure that they were aware of their parent’s HIV status, by asking them a series of open-ended questions about their family, their relationship with their parent, and their knowledge of different types of diseases, including HIV. If the child mentioned the parent’s HIV at any point in response to the screening questions, the interviewer began the interview. All children indicated that they knew of parents’ HIV infection. On average, semi-structured interviews lasted 1½ h with parents and caregivers, and 1 h with children and adult children.

Data Analysis

Audiotaped interviews were transcribed and text documents were managed with a qualitative data analysis program. Content analysis of the narratives was conducted with a combination of inductive and deductive techniques (Bernard, 2002). Such analysis allows for a full range of themes to emerge, including those that were not anticipated prior to analysis. Following Bernard’s (2002) protocol for content analysis, we created a set of exhaustive and mutually exclusive codes, applied the codes systematically to the narratives, and then tested the reliability between coders. Specifically, a member of the project team who was well-versed in stigma research (i.e., the first author) initially read through a sample of transcripts to identify the presence of text related to stigma. Coders were given a basic operational definition of stigma that was derived from prior literature (Goffman, 1963) and instructed to identify all stigma-related text in the narratives (including stigma related to HIV and other social categories such as race/ethnicity, gender, and exposure/risk). The first author then read through the stigma-related text and resolved any discrepancies between coders. This procedure resulted in a body of 230 stigma-related quotations across all 33 families interviewed. The stigma sections of the text averaged approximately 11 (SD 5) lines per quote on average at about 20 words per line overall; 11 (SD 7) lines for mothers; 13 (SD 11) lines for fathers; 11 lines (SD 7) for adult children; 9 (SD 5) lines for children; and 11 lines (SD 5) for caregivers.

Once the coders and first author agreed on the body of stigma segments of the narratives, the first author trained the coders to identify instances of felt, enacted, and courtesy stigma, as defined by prior research (Goffman, 1963; Hebl & Mannix, 2003; Link et al., 2001; Scambler, 1989, 1998) The two coders then sorted the body of stigma-related quotations into distinct piles based on similarities, representing the themes of felt, enacted, and courtesy stigma (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Ryan & Bernard, 2003). As recommended by qualitative methodology researchers (Bernard, 2002; Spradley, 1979), these coding categories were mutually exclusive and exhaustive. After the themes were marked by the coders, the first author examined the codes and suggested revisions as appropriate; any disagreements between the first author and the coders were discussed and resolved. Cohen’s Kappa was used to check consistency between the two coders (Cohen, 1960). According to conventions on the use of Kappa for interrater agreement (Bakeman & Gottman, 1986; Fleiss, 1981; Landis & Koch, 1977), the consistency between the coders was satisfactory (felt stigma = 0.80; enacted stigma = 0.70; courtesy stigma = 0.71).

Inductive methods were used to derive understanding regarding the interconnectedness and shared experiences of stigma experiences within the family. For the primary analysis of the narratives, all stigma quotations, regardless of stigma category, were grouped by family unit. Thus, descriptions of the results in families as a whole include narratives about stigma among any member of the family unit (i.e., caregivers, children, adult children, and parents). In a secondary analysis to explore differences in families’ HIV stigma experiences by social category, families’ narratives were organized by family within each level of race/ethnicity and exposure/risk group. Differences by race/ethnicity and exposure/risk group were examined in separate analyses. Specifically, we compared the types of stigma discussed and themes that emerged in narratives by race/ethnicity and exposure/risk group.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In the parent sample, 48% were African American, 3% American Indian, 21% Latino, and 27% White. Most (73%) were mothers, and the mean age of parents was 44 years (SD 7; range 30–62). The sample was of relatively low socio–economic status: almost half (48%) reported annual household incomes of $10,000 or less, a quarter reported annual household incomes of $10,001–$25,000, and only 12% reported annual household incomes greater than $25,000. Over 40% had less than a high school education, 36% had a high school diploma or GED, 18% reported some college, and only 3% had a 4-year college degree or a higher level of education. Of the nine fathers in the sample, five (56%) reported their exposure/risk risk group to be injection drug use, and four (44%) reported their risk group to be sex with men. Of the 24 mothers, 4 (17%) reported their exposure/risk risk group to be injection drug use, 16 (24%) reported their risk group to be heterosexual sex, and 4 (17%) reported their risk group as “other.” Two-thirds (67%) of parents lived with their spouse or partner. A total of 36% had been diagnosed with HIV before 1990, 42% between 1990 and 1993, and 21% between 1994 and 1996.

Of the 46 children in the sample, 59% were 9–17 years old (hereafter referred to as “children”) and 41% were 18 years of age or older (hereafter referred to as “adult children”). The majority of children were male (63%) and the majority of adult children were female (58%). Children’s mean age was 14 years (SD 2; range 9–17), and adult children’s mean age was 22 years (SD 4; range 18–30). Caregivers were the infected parent’s spouse or partner (73%; six females and five males), mother (13%), and friend (13%). Caregivers’ mean age was 46 years (SD 11, range 35–79).

Stigma-related Themes

Table 1 shows the percentages of family members who discussed the different types of stigma. At least one family member (i.e., caregiver, child, adult child or parent) in all of the families described experiences with HIV stigma. Felt stigma was the largest stigma category represented in the narratives of PWH and their families; enacted stigma was the second largest. Nearly all families across categories detailed their fears regarding prejudice and discrimination, and the majority of families recounted actual experiences with prejudice and discrimination. Only one-tenth of families discussed courtesy stigma.

Felt Stigma

Disclosure as Intertwined with Felt Stigma

Across all families, the primary stigma-related theme was lack of serostatus disclosure due to felt stigma. This theme, which was present in the narratives of parents, caregivers, and children within the same families, represented a shared experience that was validated by all members of the family. Due to high levels of felt stigma and discrimination, an atmosphere of secrecy surrounded many families living with HIV/AIDS. Parents were reluctant to disclose to children because they feared that their children would disclose to others who would then discriminate against the children. When parents did disclose, they paired many of their disclosure messages with warnings about the possibility of prejudice and discrimination from other family members, friends, and teachers. As one mother with HIV noted, stigma complicates disclosure of HIV, more than disclosure of other diseases: “If it was cancer or a brain tumor, every parent would tell their child, no big deal. But because of what it is, it just doesn’t sound good.”

People with HIV and caregivers who did disclose warned their children about the stigma that they might face if others knew about the HIV infection. Parents cautioned children that they could be insulted and teased, and that they could lose friends. A mother with HIV said, “I’ve explained how terrible people can be to kids – I’ve really scared them because I’ve told them that...kids can be really cruel and they might say things.” Many similar instances of PWH warning their children were evident in the narratives.

In families in which parents disclosed their HIV status to children, children heeded parents’ advice about not telling their friends and were similarly worried about experiencing stigma. One child stated that she did not disclose her mother’s HIV status “so I don’t have to be hurt. So I don’t have to...see [people] looking at me or my family in different ways.” An adult child also noted, “I might have a fear that they might talk about me. Or think about me in a certain way. Or they just don’t want to hang out with me anymore.” Across families, children who were aware of their parent’s HIV status felt protective of their parent and worried about mistreatment. An adult child said of his father, “I’m worried if they do find out, how would they act towards him. He’s a good man and for people to just shun him ‘cause of something that he had no choice [about]...that’s doing him an injustice.”

Parents who chose not to disclose felt that they were protecting their children. As described by a mother with HIV, “I’m trying to protect [them] from the evils of society...the longer I can keep them in the most normal path for kids their age, the better. Without that added stress and fear and worry that comes along with the knowledge.” Others had heard of terrible instances of discrimination against children, which alerted them to the possibility of their own children experiencing stigma. For example, one caregiver, the wife of a person with HIV, had a friend whose children were abused by classmates who knew that their mother was HIV-positive: “...one daughter, her head was flushed down the toilet bowl...I said, oh my God, let us not tell ours [about their father’s HIV]...So they just don’t blurt it out to everybody.” Caregivers similarly tried to protect their children by not disclosing, as noted by another spouse and mother: “I don’t want my daughter to feel like because of us she has to be away from people or think somebody’s gonna talk about her.”

Felt Stigma as a Basis for Decisions about Disclosure to Individuals Outside of the Family

Several family members made the decision to disclose or not to disclose after looking for indicators of prejudicial attitudes among other family members and friends who were unaware of the parent’s HIV status. In some cases, PWH and their caregivers overheard hurtful comments or verbal insults about PWH, usually from family members or friends who did not know that they were infected. PWH were less inclined to disclose if they observed such indicators of prejudice. For instance, one husband of a woman with HIV noted that his parents spoke about HIV “in such a derogatory way... there just wouldn’t have been no talking to them, so I decided to keep it between me, my wife, and my son.” Another girl explained how she decided whether to disclose to a friend: “If we were talking about HIV in class and if that person acted all like nasty...if they acted like they didn’t like it or they didn’t want to be around that person then I wouldn’t tell them. But if they were just forward and be okay with it then maybe I would tell them.”

Effects of Felt Stigma and Nondisclosure on the Family

Parents, children, and caregivers who successfully hid the HIV from others shared experiences of stress and loneliness. Although they found social support within their immediate family, PWH and their family members were unable to rely on others who were outside of the family for full support. Family members spoke of not being able to have close relationships with friends, and of their fear of losing friends if the HIV were revealed. As one female caregiver, a partner of a father with HIV, maintained: “I never found a friend, even though I’m close to some people...I just figure if I tell somebody then this person’s gonna tell somebody.” A teenager with an HIV-infected parent spoke of the difficulties in sustaining friendships with peers who held prejudicial attitudes: “I wish that I could talk to them about it in my class, but they make fun of people who have it...it’s hard knowing my mom has HIV and they would make fun of it.” Describing the isolation of having HIV, a mother said, “it’s good to have someone to talk to, it’s no good to keep it locked up inside, that’s bad, that will literally kill you. Not the disease but being isolated. It’ll kill you.”

Enacted Stigma against PWH

Interpersonal discrimination from close family members (e.g., parents, siblings, and children) and friends emerged as the primary enacted stigma-related theme in families’ narratives. PWHs’ experiences were corroborated by children and caregivers within their family, and included avoidance, ostracism, and verbal insults. In general, much of the rejection seemed to stem from a fear of HIV infection, and a lack of knowledge about the way that HIV is transmitted. Other types of enacted stigma due to HIV, including violence and structural discrimination from institutions such as health care and employment settings, did not commonly emerge in stigma narratives.

Many parents with HIV spoke of being completely avoided or ostracized by family members and friends who heard of their infection. Other family members remained in contact with HIV-infected participants, but their interactions were punctuated by overt acts of discrimination and hurtful remarks. Such discrimination tended to be based on unfounded fears of infection. A common response to such fears was to dispose of utensils used by the infected individual, or to refuse to eat food prepared by a person with HIV. For example, one mother with HIV was told that her sister had disposed of all of the spoons in her mother’s house after she had eaten there. Another mother with HIV similarly related that her former in-laws started treating her differently after disclosure: “She’d give me a separate bowl of dip at the table...[before,] he would always kiss me on the lips...[after,] he started kissing me on the cheek.”

As reported by parents with HIV, family members and friends also feared that children could be infected by any contact with PWH: “One day my mother told me, ‘do not touch my nephew or my nieces.’ My sister in law...was afraid that I was going to give them [HIV]...for quite some time she didn’t let me get near the kids...she told... my brother to tell my mother to tell me to stay away from her kids.” A child of a mother with HIV “...was told not to eat the food that I cooked because she could get AIDS and die. So after she would eat, not to hurt my feelings, she would go to the bathroom and purge, stick her fingers down her throat.” Other PWH reported similar experiences, in which they were, for instance, not allowed to hold babies or interact with small children. Within the same families, caregivers and children corroborated PWH’s reports of stigma and discrimination, especially with regard to avoidance. They observed that other family members would discard plates or would drink from different glasses than those used by the person with HIV.

Caregivers also experienced stigma directly, from friends who did not understand their decision to remain with their infected partner. A caregiver related that her friends wondered why she would stay with an HIV-infected partner: “They...said, ‘Why do you stay?’ And I’ve heard [of] women who they found out their husband was HIV+, honey, the bed wasn’t even cold. They packed up their bags up and left. They said, ‘I didn’t sign up for a life of this.’” In such instances, family members experienced stigma due to the HIV status of their partner, in the form of other people questioning the decision to support their partner.

Courtesy Stigma against Family Members of PWH

Courtesy stigma against children and caregivers of PWH was discussed to a much lesser extent than were enacted and felt stigma. These experiences were described by family members, as well as some PWH, who were aware that their family members had experienced discrimination. A few children reported losing friends due to their parent’s HIV status, usually because friends’ parents prohibited the friendship. For instance, one young adult child was angered by the insensitive remarks of a friend’s mother: “She said she told me that she’s afraid for her daughter to be with me ‘cause she doesn’t know what I got from my mom.” Another young adult child was rejected by a friend when he was younger: “I told my friend and he told his parents and his parents never allowed him to talk to me anymore.”

Caregivers described courtesy stigma experiences, in which friends and some extended family members avoided children and caregivers, as well as the parent with HIV. Friends and extended family members sometimes showed irrational fears of contagion, in which they were afraid that a caregiver, or objects in a caregiver’s house, could transmit HIV. One caregiver’s friend “really flipped out” and worried that she could get the infection from eating and sleeping at the caregiver’s house, which she shared with her infected partner.

From Internalized Stigma to Acceptance

In addition to experiencing HIV stigma from outside of the family, PWH and their families struggled with their own internalized negative attitudes about HIV. Parents with HIV and their families discussed how their initial feelings of stigma had changed over time, especially after receiving information about HIV/AIDS and routes of transmission. As one father noted, who had been infected through sex with men, his oldest daughter’s homophobia and negative attitudes about PWH changed once she learned more about HIV/AIDS. Initially, she was afraid of being infected, but “now she’s coming around and she spends a lot more time with me than previous years...I actually had to sit her down and explain to her and get literature that I had with proven facts.” The father added that his child’s mother has been instrumental in helping her to understand HIV and accept her father again: “...now everything is pretty cool...she’s not as fearful...the affection that was once lost has kind of returned.” Another father found that people’s attitudes changed once they were educated about the disease: “In the beginning, she didn’t want me being around the kids. I had to educate her how it is transmitted and the infections in bodily fluids. People are often ignorant about it. They don’t particularly understand. They think it’s going to go away. But it’s not.”

Children’s and caregivers’ narratives confirmed and validated the stories of PWH. For example, a caregiver related that the entire immediate family experienced rejection after learning of the HIV infection, but that relationships had been gradually re-established over time. Children discussed how their attitudes had changed from the time they first learned of parents’ serostatus. Some children were initially ashamed of or angry with their parent, but over time, many of their emotions turned to worry and feelings of protectiveness. As one young adult child noted, “I’m not embarrassed no more, I used to be.” Another young adult child in the same family recognized the difference in her attitudes as a child versus an adult: “I’m not afraid to talk about it. Not anymore, I’m not, you know. But being a teenager in high school you’re scared of what your peers [are] gonna say. But as far as me being an adult, not at all.”

In addition to the changing attitudes of family members, a few PWH noted that they, too, had to adjust their thinking about HIV. Some recounted times that they had held prejudicial attitudes or discriminated against PWH before they knew that they were infected. One mother indicated, “You know, before I had this disease, I looked at people badly. And it hurts for me to say. How could they do that? Why do they do that, sleeping around? My high and mighty standards, lo and behold, now I have the disease.” Likewise, a mother, looked back to when she discovered that friends had HIV, before she was diagnosed herself: “I found out two of my friends had AIDS, I didn’t go near them, I didn’t want them near me, I didn’t want them near my kids, I kept my kids home from school, I went ballistic over the whole AIDS epidemic...so, needless to say, he died and I never did go to see him or nothing and then I found out I was HIV positive.” These participants were saddened by the realization that their own prejudices had hurt others with the disease.

Differences in Stigma Experiences by Social Category

The major themes identified for felt, enacted, and courtesy stigma in families’ narratives emerged across the race/ethnicity and exposure/risk group of the individual with HIV. Across groups, families were reluctant to disclose to children due to felt stigma, and many experienced discrimination due to misconceptions about HIV.

Some participants discussed the compounded stigma of living with HIV in the context of another devalued social category related to gender, race/ethnicity, or exposure/risk group. Women, in particular, discussed the compounded stigma of being HIV-positive and female. A pregnant woman with HIV felt the negative attitudes about health care providers when she was diagnosed prior to the introduction of antiretroviral medications for preventing the infection of babies: “Back in ‘93...they didn’t have any protocol for treating women with HIV...Pregnant and HIV positive, you were like a taboo. They wouldn’t touch you.” Another pregnant woman, the partner of a person with HIV, was questioned by her family: “My family...they still question how I could have gotten pregnant, ‘You don’t touch him or anything, right? You don’t have sex with him or anything, right?’”

Awareness of stereotypes about PWH as sexually promiscuous, gay, and substance-using seemed to be related to strong feelings of felt stigma, especially among women who were infected by their male partners. Such women tended to distance themselves from these stereotypes and felt that they would be blamed unfairly for their disease. As one mother said, “I’m afraid to disclose to [my daughter] ‘cause she’ll go tell her friend [who would] tell her parents...everyone has the [stereotype] that people with HIV are dirty or druggies or prostitute, lesbian or gay. I don’t fall into any of them.’” Children were attuned to mothers’ felt stigma due to stereotypes, as indicated by one adult child: “She doesn’t want these people to know...I think she has some sort of feelings of shame or something attached to it and she thinks people will think of her a certain way if they know she has it.”

Women also described feelings of isolation from medical or social service organizations that they perceived to target other groups with the disease. For example, an African American mother said: “Most of those [clinics for people with HIV], people tend to think that they’re geared toward gay people...For the Black American...there should be some other places they can go to get help...some people are embarrassed to go to those places.” Another mother described how she overcame her initial reluctance to be involved with a support group for PWH: “Everybody there was drug-related or sexually getting it, by tramping around. I didn’t belong there because I was raped.”

As compared to women’s discussion of HIV stigma in the context of gender, fewer participants described added stigma burden from other social categories. One gay father with HIV, who experienced prejudice from his mother and other family members, said: “I don’t wish anybody being gay. It’s no use to life. Being gay with HIV—that’s the worst thing...everywhere you have to hide or try to change.” A father who had contracted HIV through injection drug use was told by his sister, “That’s what you get.” In general, such discussions were rare across interviews.

Discussion

In the present qualitative analysis, felt stigma emerged as the most common stigma-related theme in families living with HIV. Within the domain of felt stigma, stigma issues were intertwined with disclosure decisions. Parents were reluctant to disclose their HIV status to children and to others outside of the family. Consistent with prior qualitative and quantitative research (Corona et al., 2006; DeMatteo et al., 2002; Ingram & Hutchinson, 1999; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Scrimshaw & Siegel, 2002; Semple et al., 1993; Vallerand et al., 2005) parents’ main concern was that their child would disclose to others, such as classmates and teachers, who would then treat the child unfairly. Our data indicated few experiences with courtesy stigma, however, possibly because many children respected parents’ wishes and did not disclose the disease to others. Although such children were protected from stigma, they experienced isolation and loneliness, as well as a lack of social support from peers.

Enacted stigma was primarily experienced as interpersonal discrimination. Many of these experiences were highlighted by a fear of contagion, in which people were uncomfortable with contact with material objects, such as a glass or utensil that were used or owned by a person with HIV. A small number of caregivers also experienced prejudice due to a fear of contagion. Other HCSUS analyses using quantitative data have indicated that about a quarter of parents infected with HIV avoided certain interactions with their child (i.e., kissing, sharing utensils, and hugging) because they feared transmitting the virus to their children (Schuster et al., 2005), and that 11% of children with HIV-infected parents worried that they could catch HIV from their parent (Corona et al., 2006). Taken together, the present and prior HCSUS findings are consistent with recent research on the general public’s fears and misconceptions about being infected with HIV (Herek & Capitanio, 1999; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006). For example, a random 1999 telephone survey in US found that a substantial percentage of respondents would be uncomfortable wearing a clean sweater (27%) or using a clean drinking glass (28%) that had been previously used by a person with HIV (Herek & Capitanio, 1999). The same survey also found that half of participants had incorrect beliefs about casual contact, including the assumption that sharing a glass with someone who has HIV can lead to transmission of the virus.

Our analysis also showed that some family members’ and friends’ initial fears about transmission changed over time, after the person with HIV educated them about the virus. These findings should be viewed with caution, because families were only eligible if the parent and the child were in recent contact with each other; children who were no longer in contact with their parent (and who were therefore not interviewed) may have had the harshest attitudes about PWH. Nevertheless, our findings regarding attitude change are consistent with prior intervention research, which suggests that skills building through, for example, mock role plays with HIV-positive individuals and contact with PWH, holds promise in reducing HIV stigma (Brown et al., 2003). Provision of HIV-related information only is less effective in reducing HIV stigma, as compared to information combined with skills building or exposure to PWH, either directly (e.g., PWH speaking with individuals or in front of groups), or indirectly (e.g., through media or recorded testimonials) (Brown et al., 2003).

Several forms of overt, enacted stigma—including structural discrimination and violence—were rarely discussed in the narratives. One explanation is that participants truly did not experience much overt discrimination. As with courtesy stigma, enacted stigma was most likely uncommon because PWH did not widely disclose their disease. Moreover, as indicated by a national survey of the general public, some overt forms of prejudice against PWH (e.g., avoidance of children with HIV by classmates) appeared to decline in US from the early to late the 1990s (Herek et al., 2002). An alternate explanation is that participants experienced overt discrimination, but they did not attribute their mistreatment to HIV stigma. Structural discrimination, such as housing or employment discrimination, may not be apparent to those who are experiencing it, because they do not have a “control” condition—that is, they do not know how individuals without HIV are treated in the same circumstances (Berkman & Kawachi, 2000). Nevertheless, due to the qualitative nature of the research and relatively small sample, one should be cautious about generalizing our results, especially with respect to the prevalence of overt stigma among PWH. We were only able to contact 28% of the HCSUS sample, and of those, 155 refused to participate. Individuals with the highest levels of felt stigma may have been less likely to participate, because they may have feared discrimination if their participation in the study became known to others who did not know their serostatus.

Some types of stigma experiences may not have been captured by our assessment, because we did not ask about stigma from HIV or other social categories directly. Thus, we cannot make conclusions regarding quantitative levels of stigma or relative differences in stigma by race/ethnicity and exposure/risk group. However, all families spontaneously discussed HIV stigma, which suggests that stigma is a particularly salient theme among families living with HIV; the probability of a given topic emerging unprompted among all (or nearly all) participants is low, unless it is strongly associated with the general interview topic (Spradley, 1979).

The present study’s results have implications for the design of family focused interventions to address stigma among all members of HIV-affected families. An existing effective family focused intervention addresses parents’ and adolescents’ psychosocial coping with negative emotions and stigma, and disclosure decisions (Rotheram-Borus, Flannery, Rice, & Lester, 2005; Rotheram-Borus, Lee, Gwadz, & Draimin, 2001). Parents and adolescents meet both separately and together in small groups to discuss these issues. The present study’s results further demonstrate a need for such family focused interventions and suggest an expansion of such interventions to include caregivers as well. In the present study, young children were profoundly affected by parents’ HIV status and shared parents’ felt stigma. However, many were forbidden to discuss their situation with others, leading to isolation and emotional distress. Children with HIV-infected parents may respond well to such group interventions, in which they can share their situations with like peers, as well as their parents and caregivers, to gain emotional support in an accepting environment.

Interventions to improve adherence to HIV treatment may also need to take into account the family context of felt stigma and disclosure in order to be effective. The stigma surrounding HIV has been implicated as a barrier to HIV treatment adherence, because patients may be reluctant to take, carry, or store medications around others who do not know their serostatus (Golin, Isasi, Bontempi, & Eng, 2002; Murphy et al., 2003; Rintamaki, Davis, Skripkauskas, Bennett, & Wolf, 2006; Siegel, Scrimshaw, & Ravies, 2000). Taking medications may be particularly difficult in families in which children or other family members are not aware of the parent’s infection. Providers may need to be sensitive to and work with patients to identify stigma concerns when prescribing medications.

Our findings also suggest ways to improve upon current quantitative scales measuring HIV stigma. Few quantitative scales exist to measure stigma experienced by PWH; of those that are available, none capture a full range of courtesy, enacted, and felt stigma experiences, or measure the attributions that PWH make for discriminatory acts (Nyblade, 2006). For example, current scales do not assess whether PWH believe that reluctance to use their utensils is due to fear of transmission. The psychological coping response to, and long-term mental health consequences of, discrimination may partially depend upon the attributions given to discriminatory events. Further, current quantitative stigma scales do not take into account the multiple layers of HIV stigma that may be experienced due to stereotypes about PWH and other social categories associated with HIV (e.g., gay/bisexual, IDU, sex worker, African American/Latino) (Reidpath & Chan, 2005). Our results suggest ways to refine current stigma scales, by including more specific items that measure a range of stigma experiences, due to stereotypes and different category memberships, as well as the attributions made for stigma.

In sum, the present study is the first to examine the interconnectedness of stigma in the family context, from the perspective of multiple family members. Our findings elucidate the types of stigma shared by PWH and their families. Felt stigma was evidenced in parents’ difficulties in disclosing to their children, and in children’s reluctance to discuss their situation with individuals outside of the family. Extended family members’ and friends’ fears of contagion seemed to be the root cause of many acts of interpersonal discrimination. Our results point to a need for effective interventions to reduce HIV stigma in the general public, and to support families living with HIV in coping with the myriad harmful effects of stigma.

References

Antle, B. J., Wells, L. M., Goldie, R. S., DeMatteo, D., & King, S. M. (2001). Challenges of parenting for families living with HIV/AIDS. Social Work, 46, 159–169.

Armistead, L., Summers, P., Forehand, R., Morse, P. S., Morse, E., & Clark, L. (1999). Understanding of HIV/AIDS among children of HIV-infected mothers: Implications for prevention, disclosure, and bereavement. Children’s Health Care, 28, 277–295.

Bakeman, R., & Gottman, J. M. (1986). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barroso, J., & Powell-Cope, G. M. (2000). Metasynthesis of qualitative research on living with HIV infection. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 340–353.

Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 24, 518–529.

Berkman, L. F., & Kawachi, I. (2000). Social epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bernard, H. R. (2002). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Brackis-Cott, E., Mellins, C. A., Abrams, E., Reval, T., & Dolezal, C. (2003). Pediatric HIV medication adherence: The views of medical providers from two primary care programs. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 17, 252–260.

Brown, L., Macintyre, K., & Trujillo, L. (2003). Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 49–69.

Chen, J. L., Philips, K. A., Kanouse, D. E., Collins, R. L., & Miu, A. (2001). Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive men and women. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 144–152, 165.

Clark, H. J., Lindner, G., Armistead, L., & Austin, B. J. (2003). Stigma, disclosure, and psychological functioning among HIV-infected and non-infected African-American women. Women and Health, 38, 57–71.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46.

Corona, R., Beckett, M. K., Cowgill, B. O., Elliott, M. N., Murphy, D. A., Zhou, A. J., & Schuster, M. A. (2006). Do children know their parent’s HIV status? Parental reports of child awareness in a nationally representative sample. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 6, 138–144.

Courtenay-Quirk, C., Wolitski, R. J., Parsons, J. T., & Gomez, C. A. (2006). Is HIV/AIDS stigma dividing the gay community? Perceptions of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18, 56–67.

DeMatteo, D., Wells, L. M., Salter Goldie, R., & King, S. M. (2002). The ‘family’ context of HIV: A need for comprehensive health and social policies. AIDS Care, 14, 261–278.

Demi, A., Bakeman, R., Moneyham, L., Sowell, R., & Seals, B. (1997). Effects of resources and stressors on burden and depression of family members who provide care to an HIV-infected woman. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 35–48.

Donenberg, G. R., & Pao, M. (2005). Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry’s role in a changing epidemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 728–747.

Fleiss, P. M. (1981). Intestinal microflora, injury and vitamin K deficiency [letter]. Nutrition Reviews, 39, 147.

Forehand, R., Steele, R., Armistead, L., Morse, E., Simon, P., & Clark, L. (1998). The family health project: Psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 513–520.

Frankel, M. R., Shapiro, M. F., & Duan, N. (1999). National probability samples in studies of low-prevalence diseases. Part 2: Designing and implementing the HIV cost and services utilization study sample. Health Services Research, 34, 969–992.

Gielen, A. C., O’Camp, P., & Faden, R. R. (1997). Women’s disclosure of HIV status: Experiences of mistreatment and violence in an urban setting. Women and Health, 25, 19–31.

Goffman E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Golin, C., Isasi, F., Bontempi, J. B., & Eng, E. (2002). Secret pills: HIV-positive patients’ experiences taking antiretroviral therapy in North Carolina. AIDS Education and Prevention, 14, 318–329.

Gostin, L. O., & Weber, D. W. (1998). The AIDS litigation project: HIV/AIDS in the courts in the 1990s, part 2. AIDS and Public Policy Journal, 13, 3–19.

Hackl, K. L., Somlai, A. M., Kelly, J. A., & Kalichman, S. C. (1997). Women living with HIV/AIDS: The dual challenge of being a patient and caregiver. Health and Social Work, 22, 53–62.

Hebl, M. R., & Mannix, L. M. (2003). The weight of obesity in evaluating others: A mere proximity effect. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 29, 28–38.

Herek, G., & Capitanio, J. (1999). AIDS stigma and sexual prejudice. American Behavioral Scientist, 42, 1126–1143.

Herek, G., Capitanio, J., & Widaman, K. (2002). HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1991-1999. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 371–377.

Ingram, D., & Hutchinson, S. A. (1999). HIV-positive mothers and stigma. Health Care for Women International, 20, 93–103.

Ingram, D., & Hutchinson, S. A. (2000). Double binds and the reproductive and mothering experiences of HIV-positive women. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 117–132.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2006). Attitudes about stigma and discrimination related to HIV/AIDS. Retrieved 9/25/06, from http://www.kff.org/spotlight/hivstigma/index.cfm.

Kang, E., Rapkin, B. D., Remien, R. H., Mellins, C. A., & Oh, A. (2005). Multiple dimensions of HIV stigma and psychological distress among Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV illness. AIDS and Behavior, 9, 145–154.

Landis, J., & Koch, G. (1977). Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174.

Lee, M. B., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (2002). Parents’ disclosure of HIV to their children. AIDS, 16, 2201–2207.

Lekas, H. M., Siegel, K., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2006). Continuities and discontinuities in the experiences of felt and enacted stigma among women with HIV/AIDS. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 1165–1190.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Link, B. G., Struening, E. L., Neese-Todd, S., Asmussen, S., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1621–1626.

Murphy, D. A., Austin, E., & Greenwell, L. (in press). Correlates of HIV-related stigma among HIV-positive mothers and their uninfected adolescent children. Women and Health.

Murphy, D. A., Roberts, K. J., & Hoffman, D. (2002). Stigma and ostracism associated with HIV/AIDS: Children carrying the secret of their mothers’ HIV+ serostatus. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11, 191–202.

Murphy, D. A., Roberts, K. J., Hoffman, D., Molina, A., & Lu, M. C. (2003). Barriers and successful strategies to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected monolingual Spanish-speaking patients. AIDS Care, 15, 217–230.

Nyblade, L. (2006). Measuring HIV stigma: Existing knowledge and gaps. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 11, 335–345.

Parker, R., & Aggleton, P. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine, 57, 13–24.

Poindexter, C. C., & Linsk, N. L. (1999). HIV-related stigma in a sample of HIV-affected older female African American caregivers. Social Work, 44, 46–61.

Powell-Cope, G. M., & Brown, M. A. (1992). Going public as an AIDS family caregiver. Social Science and Medicine, 34, 571–580.

Reidpath, D. D., & Chan, K. Y. (2005). A method for the quantitative analysis of the layering of HIV-related stigma. AIDS Care, 17, 425–432.

Relf, M. W. (2005). HIV-related stigma among persons attending an urban HIV clinic. Journal of Multicultural Nursing and Health, 11, 14–22.

Reyland, S. A., Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., & McMahon, T. J. (2002). Tell them you love them because you never know when things could change: Voices of adolescents living with HIV-positive mothers. AIDS Care, 14, 285–294.

Rintamaki, L. S., Davis, T. C., Skripkauskas, S., Bennett, C. L., & Wolf, M. S. (2006). Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 20, 359–368.

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Flannery, D., Rice, E., & Lester, P. (2005). Families living with HIV. AIDS Care, 17, 978–987.

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Lee, M. B., Gwadz, M., & Draimin, B. (2001). An intervention for parents with AIDS and their adolescent children. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1294–1302.

Ryan, G., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15, 85–109.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003a). Motherhood in the context of maternal HIV infection. Research in Nursing and Health, 26, 470–482.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003b). Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Research in Nursing and Health, 26, 153–170.

Scambler G. (1989). Epilepsy. London: Routledge.

Scambler, G. (1998). Stigma and disease: Changing paradigms. Lancet, 352, 1054–1055.

Schuster, M. A., Collins, R., Cunningham, W. E., Morton, S. C., Zierler, S., Wong, M., Tu, W., & Kanouse, D. E. (2005). Perceived discrimination in clinical care in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults receiving health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 807–813.

Schuster, M. A., Kanouse, D. E., Morton, S. C., Bozzette, S. A., Miu, A., Scott, G. B., & Shapiro, M. F. (2000). HIV-infected parents and their children in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1074–1081.

Scrimshaw, E. W., & Siegel, K. (2002). HIV-infected mothers’ disclosure to their uninfected children: Rates, reasons, and reactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 19–43.

Semple, S. J., Patterson, T. L., Temoshok, L. R., McCutchan, J. A., Straits-Troster, K. A., Chandler, J. L., & Grant, I. (1993). Identification of psychobiological stressors among HIV-positive women. Women and Health, 20, 15–36.

Shapiro, M. F., Berk, M. L., & Berry, S. H. (1999). National probability samples in studies of low-prevalence diseases. Part 1: Perspectives and lessons from the HIV cost and services utilization study. Health Services Research, 34, 951–968.

Siegel, K., Scrimshaw, E. W., & Ravies, V. H. (2000). Accounts for non-adherence to antiviral combination therapies among older HIV-infected adults. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 5, 29–42.

Sowell, R. L., Seals, B. F., Moneyham, L., Demi, A., Cohen, L., & Brake, S. (1997). Quality of life in HIV-infected women in the south-eastern United States. AIDS Care, 9, 501–512.

Spradley J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Vallerand, A. H., Hough, E., Pittiglio, L., & Marvicsin, D. (2005). The process of disclosing HIV serostatus between HIV-positive mothers and their HIV-negative children. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 19, 100–109.

Vanable, P. A., Carey, M. P., Blair, D. C., & Littlewood, R. A. (2006). Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 473–482.

Wiener, L. S., Battles, H. B., & Heilman, N. E. (1998). Factors associated with parents’ decision to disclose their HIV diagnosis to their children. Child Welfare, 77, 115–135.

Wood, J. V. (1996). What is social comparison and how should we study it? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 520–537.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD40103, PI: Schuster) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48/DP000056, PI: Schuster). The writing of this paper was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH072351, PI: Bogart). The original data collection was supported in part by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (U-01HS08578). We would like to thank Marc Elliott for his assistance with the statistical sampling methodology; Theresa Nguyen and Jennifer Patch for their research assistance; Michelle Parra for her valuable contributions to conducting the study; and the interviewers and data transcribers who worked on this project. In addition, we are grateful to the HCSUS Consortium for making the study possible and the study participants for sharing their time and stories.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bogart, L.M., Cowgill, B.O., Kennedy, D. et al. HIV-Related Stigma among People with HIV and their Families: A Qualitative Analysis. AIDS Behav 12, 244–254 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9231-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9231-x