Abstract

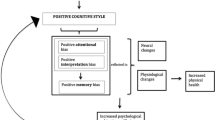

The inverse relationship between social support and depression has been robust to a wide variety of conceptual replications with college, community, and clinical samples. However, there is inadequate understanding of the mechanisms by which social support protects against depression. In this paper, we define a subtype of social support, adaptive inferential feedback, which is more precise than the general concept of social support. We elaborate two possible mechanisms for the beneficial effect of adaptive inferential feedback on depression by incorporating this type of social support into a specific etiological model of depression, the Hopelessness Theory of depression. Empirical tests are conducted for the two hypothesized mechanisms by which adaptive inferential feedback protects against depression as well as the full expanded Hopelessness Theory proposed herein. Our results supported both the specific mechanisms proposed as well as the full expanded hopelessness theory. We found that adaptive inferential feedback predicts more positive inferences for stressful events and a more positive inferential style prospectively. It also interacts with cognitive risk and stress to predict future hopelessness and depressive symptoms as well as concurrent diagnoses of hopelessness depression over and above the contributions of stress, cognitive risk, and general social support which are known predictors of depressive symptoms and disorders. Thus, this newly defined subtype of social support may be an important contributor in the etiology of hopelessness depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In as much as the measure of Adaptive Inferential Feedback was newly developed for this study, we originally tested each of the hypotheses separately for general social support and Adaptive Inferential Feedback. Both sets of analyses yielded results in support of each point of impact as well as the overall model. Therefore, we decided to subject the new Adaptive Feedback measure to the more rigorous test of determining if it contributed to explaining variance in hopelessness and depression after controlling for the more established general social support measure.

Given that there is no previous work indicating which of the vulnerability factors (negative inferential style, stress, or poor AIF) might be more potent, no specific predictions about how groups who have the same number of vulnerability factors might differ are offered.

Note that a correction for attenuation calculation (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) indicated a maximum possible correlation of .70 between the IQ and the measure of AIF.

Up to three supporters were reported to allow for the possibility that conflicting feedback might occur from close confidants. A person who receives both highly adaptive and highly maladaptive feedback will be lower overall on AIF than one who receives highly adaptive feedback only. Given prior research indicating that a single confident can be a potent buffer against depression (Brown & Harris, 1978), no additional weighting was given for having more than one confidant.

Keep in mind that the SSI-Fit score is essentially a measure of unmet social support needs so we expect negative correlations between SSI-Fit scores and the AIFQ for which higher scores indicate more adaptive inferential (social) feedback.

In fact, the social support measures were developed and given on schedule at the second assessment (6 weeks into the study) of the CVD project, but an incorrect version of the AIF was erroneously given to approximately one-third of the participants. All analyses reported here were also conducted on the smaller sample who received the correct version of the AIF at the earlier point in the CVD project and the results were the same as those reported here.

These missing data were primarily due to participants indicating on the AIFQ that they did not seek support from anyone regarding any stressful events during the previous 6-week interval and, therefore, leaving the remainder of the AIFQ blank.

Inferential style was assessed at the baseline of the study. Social support, stress and AIF were assessed regularly. For this analysis, the social support, stress and AIF measures were all taken from Time 1.

Some of the symptoms hypothesized to be part of the Hopelessness Depression syndrome (e.g., sadness, suicidal ideation) are completely overlapping with symptoms that are part of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for major depression, others only partially overlap with symptoms for major depression (e.g., retarded initiation of voluntary responses). In addition, some symptoms currently described as part of major depression, such as anhedonia, guilt, irritability, and appetite disturbance, are not hypothesized to be part of the Hopelessness Depression syndrome (Abramson et al., 1989; Alloy & Clements, 1992).

The groups are as follows: (1) Low risk/low AIF/low stress; (2) Low risk/low AIF/high stress; (3) Low risk, high AIF/low stress; (4) Low risk/high AIF/high stress; (5) High risk/low AIF/low stress; (6) High risk/low AIF/high stress; (7) High risk/high AIF/high stress; and (8) High risk/high AIF/low stress.

This is the result of the last step of a hierarchical regression in which all main effects and two-way interactions were entered prior to the 3-way interaction of stress, inferential style, and AIF.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., Hankin, B. L., Haeffel, G. J., MacCoon, D. G., & Gibb, B. E. (2002). Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression in a self-regulatory, psychobiological context. In I. H. Gotlib & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (3rd ed., pp. 268–294). New York: Guilford Press.

Abramson, L. Y., Alloy, L. B., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Cornette, M., Akhavan, S., & Chiara, A. (1998). Suicidality and cognitive vulnerability to depression among college students: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 473–487.

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1999). The Temple—Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression (CVD) project: Conceptual background, design, and methods. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 13, 227–262.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Hogan, M. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Rose, D. T., Robinson, M. S., Kim, R. S., & Lapkin, J. B. (2000). The Temple—Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 403–418.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Panzarella, C., & Rose, D. T. (2005). Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 145–156

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Safford, S. M., & Gibb, B. E. (2005). The Cognitive Vulunerability to Depression (CVD) Project: Current findings and future directions. In L. B. Alloy & J. H. Riskind (Eds.), Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders (pp. 33–61). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Alloy, L. B., & Clements, C. M. (1992). Illusion of control: Invulnerability to negative affect and depressive symptoms after laboratory and natural stressors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 234–245.

Amenson, C. S., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1981). An investigation into the observed sex difference in prevalence of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 1–13.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barnett, P. A., & Gotlib, I. H. (1988). Psychosocial functioning and depression: Distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychological Bulletin, 104, 97–126.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row.

Beck, A. T. (1987). Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 1, 5–37.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: The Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Garbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 77–100.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 982–986.

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865.

Brown, G. W., Andrews, B., Harris, T., Adler, Z., & Bridge, L. (1986). Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychological Medicine, 16, 813–831.

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. London: Tavistock.

Brown, S. D., Alpert, D., Lent, R. W., Hunt, G., & Brady, T. (1988). Perceived social support among college students: Factor structure of the Social Support Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35, 472–478.

Brown, S. D., Brady, T., Lent, R. W., Wolfert, J., & Hall, S. (1987). Perceived social support among college students: Three studies of the psychometric characteristics and counseling uses of the Social Support Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 337–354.

Brugha, T. S., Bebbington, P. E., Stretch, D. D., MacCarthy, B., & Wykes, T. (1997). Predicting the short-term outcome of first episodes and recurrences of clinical depression: A prospective study of life events, difficulties, and social support networks. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58, 298–306.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohen, S. (1992). Stress, social support, and disorder. In H. O. F. Veiel, & U. Baumann (Eds.), The meaning and measurement of social support (pp. 109–124). New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corp.

Cohen, S., Sherrod, D. R., & Clark, M. S. (1986). Social skills and the stress-protective role of social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 963–973.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Coyne, J. C. (1976). Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry, 39, 28–40.

Coyne J. C. (1990). Interpersonal processes. in depression. In G. I. Keitner (Ed.), Depression and families: Impact and treatment (pp. 31–53). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Dobkin, R. D., Panzarella, C., Nesbitt, J., Alloy, L. B., & Cascardi, M. (2004). Adaptive inferential feedback, depressogenic inferences, and depressed mood: A laboratory study of the expanded hopelessness theory of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33(1), 41–48.

Dobson, K. S. (1989). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 414–419.

Dunkel-Schetter, C., & Bennett, T. L. (1990). Differentiating the cognitive and behavioral aspects of social support. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 267–296). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Elliott, T. R., Marmarosh, C., & Pickelman, H. (1994). Negative affectivity, social support, and the prediction of depression and distress. Journal of Personality, 62(3), 299–319.

Endicott, J., & Spitzer, R. A. (1978). A diagnostic interview: The schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 837–844.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Rose, D. T., Whitehouse, W. G., Donovan, P., Hogan, M. E., Cronholm, J., & Tierney, S. (2001a). History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 425–446.

Gibb, B. E., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Rose, D. T., Whitehouse, W. G., & Hogan, M. E. (2001b). Childhood maltreatment and college students’ current suicidal ideation: A test of the hopelessness theory. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31, 405–415.

Gibbon, M., McDonald-Scott, P., & Endicott, J. (1981). Mastering the art of research interviewing: A model training procedure for diagnostic evaluation. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Gibbons, F. X., Benbow, C. P., & Gerrard, M. (1994). From top dog to bottom half: Social comparison strategies in response to poor performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 638–652.

Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1991). Downward comparison and coping with threat. In J. Suls, & T. A. Wills (Eds.), Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 317–345). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gotlib, I. H., & Beatty, M. E. (1985). Negative responses to depression: The role of attributional style. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 9, 91–103.

Gurtman, M. B. (1987). Depressive affect and disclosures as factors in interpersonal rejection. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 41–54.

Harlow, R. E., & Cantor, N. (1995). To whom do people turn when things go poorly? Task orientation and functional social contracts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 329–340.

Hilton, J. L., & von Hippel, W. (1996). Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 237–271.

Hollon, S. D., Shelton, R. C., & Loosen, P. T. (1991). Cognitive therapy and psychopharmacotherapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 88–99.

Hollon, S. D., Thase, M. E., & Markowitz, J. C. (2002). Treatment and prevention of depression. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 3, 39–77.

Johnson, J. G., Alloy, L. B., Panzarella, C., Metalsky, G. I., Rabkin, J. G., Williams, J. B. W., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Hopelessness as a mediator of the association between social support and depressive symptoms: Findings of a study of men with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 1056–1060.

Joiner, T. E. Jr., Alfano, M. S., & Metalsky, G. I. (1993). When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance-seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 165–173.

Joiner, T. E. Jr., Metalsky, G. I., Katz, J., & Beach, S. R. H. (1999). Excessive reassurance-seeking and depression. Psychological Inquiry, 10, 269–278.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 233–265). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lakey, B., & Cassady, P. (1990). Cognitive processes in perceived social support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 337–343.

Lara, M. E., Leader, J., & Klein, D. N. (1997). The association between social support and course of depression: Is it confounded with personality? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 478–482.

Monroe, S. M., & Roberts, J. R. (1990). Definitional and conceptual issues in the measurement of life stress: Problems, principles, procedures, progress. Stress Medicine, 6, 209–216.

Monroe, S. M., & Steiner, S. C. (1986). Social support and psychopathology: Interrelations with preexisting disorder, stress, and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95, 29–39.

Multon, K. D., & Brown, S. D. (1987). A preliminary manual for the Social Support Inventory (SSI). Chicago: Loyola University of Chicago, Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology.

Nadler, A. (1997). Personality and help-seeking: Autonomous versus dependent seeking of help. In G. R. Pierce, & B. Lakey (Eds.), Sourcebook of social support and personality (pp. 379–407). New York: Plenum Press.

Needles, D. J., & Abramson, L. Y. (1990). Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: Testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 156–165.

Panzarella, C., Dobkin, R., Truesdell, K., Cascardi, M., & Alloy, L. B. (2005). Introducing a measure of adaptive feedback: Instrument development and psychometric properties of the Social Feedback Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript.

Peterson, C., Semmel, A., von Baeyer, C., Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1982). The attributional style questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 6, 287–299.

Pierce, G. R., & Lakey, B. (1997). Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum Press.

Pietromonaco, P. R., Rook, K. S., & Lewis, M. A. (1992). Accuracy in perceptions of interpersonal interactions: Effects of dysphoria, friendship, and similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 247–259.

Roberts, J. E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1997). Social support and personality in depression: Implications from quantitative genetics. In G. R. Pierce, & B. Lakey (Eds.), Sourcebook of social support and personality (pp. 187–214). New York: Plenum Press.

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 173–220). New York: Academic Press.

Ross, L. T., Lutz, C. J., & Lakey, B. (1999). Perceived social support and attributions for failed support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 896–909.

Sarason, B. R., Sarason, I. G., & Pierce, G. R. (1990). Social support: An interactional view. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Shapiro, R. W., & Keller, M. B. (1979). Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE). Boston, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital.

Spitzer, R. L., & Endicott, J. (1978). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change version. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Spitzer, R. L., Endicott, J., & Robins, E. (1978). Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 773–782.

Swann, W. B. Jr., Wenzlaff, R. M., & Tafarodi, R. W. (1992). Depression and the search for negative evaluations: More evidence of the role of self-verification strivings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 314–317.

Weissman, A., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scales: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto, Canada.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH 48216 to Lauren B. Alloy and a Dissertation Grant from the Temple University Psychology department to Catherine Panzarella. It was based on a dissertation submitted to Temple University by Catherine Panzarella under the direction of Lauren B. Alloy. We thank the other members of the dissertation committee, Jay Efran, Catherine Hanson, Philip Kendall, and Robert Lana, for their valuable feedback and assistance. We also thank Alan Lipman for his contributions to early discussions on this topic and Gary Marshall, Laura Murray, Lou Spina, and Debra Staples for their help with data management and access.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Adaptive Inferential Feedback Questionnaire Panzarella, Lipman, & Alloy, 1990

1. Please describe the most stressful event or situation that you have been dealing with over the past week in the space below.

2. Please list below the FIRST NAME and LAST INITIAL of up to THREE people who talked with you about this stressful event. Also please describe their relationship to you (family member, boyfriend/girlfriend/spouse, friend, other):

1 = family member

2 = boyfriend/girlfriend/spouse

3 = friend

4 = other

First name and last initial | Relationship | |

|---|---|---|

Person 1 | ||

Person 2 | ||

Person 3 |

3. Please indicate with an “X” in the appropriate boxes below if, as a result of PERSON 1, PERSON 2, and PERSON 3 talking with you, you have felt better, worse, or the same about the stressor. Put “NA” (for “not applicable”) whenever there was no person named above or if they did not say or indicate anything about the stressor. For example, if you listed two persons in Question 4 (two persons with whom you talked about the stressful event), then write “NA” in the row next to PERSON 3 below:

WORSE | BETTER | THE SAME | |

|---|---|---|---|

PERSON 1 made me feel | |||

PERSON 2 made me feel | |||

PERSON 3 made me feel |

Questions 4–7 ask you what Persons 1, 2, & 3 have told you about the stressor listed in Question 1. FOR EACH QUESTION, the responses from which you may choose are listed and described below the question. SELECT the number of the response that best characterizes what EACH of the persons that you identified in Question 4 indicated to you about the stressor. Then, PLACE THE RESPONSE NUMBER WHICH YOU SELECT IN THE BOXES NEXT TO PERSONS 1, 2, & 3. If you did not select three persons in Question 4, then write “NA” in the boxes for which there is no person identified, or if the person did not say or indicate anything about the occurrence of the stressor.

4. What did Person 1, Person 2, & Person 3 indicate to you about whether the cause of the stressor has to do with this particular circumstance or if it will lead to problems in other areas of your life?

Please put one of the response numbers listed below in the boxes next to Person 1, Person 2, and Person 3.

RESPONSE NUMBERS:

0 = completely unlikely to lead to other problems

1 = very unlikely to lead to other problems

2 = somewhat unlikely to lead to other problems

3 = somewhat likely to lead to other problems

4 = very likely to lead to other problems

5 = completely likely to lead to other problems

RESPONSE# | |

|---|---|

PERSON 1 | |

PERSON 2 | |

PERSON 3 |

5. What did Person 1, Person 2, & Person 3 indicate to you about whether the cause of the stressor is something that will frequently be causing problems?

Please put one of the response numbers listed below in the boxes next to Person 1, Person 2, and Person 3.

0: completely unlikely to frequently cause problems

1: very unlikely to frequently cause problems

2: somewhat unlikely to frequently cause problems

3: somewhat likely to frequently cause problems

4: very likely to frequently cause problems

5: completely likely to frequently cause problems

RESPONSE# | |

|---|---|

PERSON 1 | |

PERSON 2 | |

PERSON 3 |

6.What did Person 1, Person 2, & Person 3 indicate to you about whether the occurrence of the stressor will lead to a lot of problems?

Please put one of the response numbers listed below in the boxes next to Person 1, Person 2, and Person 3.

0: completely unlikely to lead to a lot of problems

1: very unlikely to lead to a lot of problems

2: somewhat unlikely to lead to a lot of problems

3: somewhat likely to lead to a lot of problems

4: very likely to lead to a lot of problems

5: completely likely to lead to a lot of problems

RESPONSE# | |

|---|---|

PERSON 1 | |

PERSON 2 | |

PERSON 3 |

7. What did Person 1, Person 2, & Person 3 indicate to you about whether the occurrence of the stressor means there is something wrong with you?

Please put one of the response numbers listed below in the boxes next to Person 1, Person 2, and Person 3.

0: completely unlikely to mean there is something wrong with me

1: very unlikely to mean there is something wrong with me

2: somewhat unlikely to mean there is something wrong with me

3: somewhat likely to mean there is something wrong with me

4: very likely to mean there is something wrong with me

5: completely likely to mean there is something wrong with me.

RESPONSE# | |

|---|---|

PERSON 1 | |

PERSON 2 | |

PERSON 3 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Panzarella, C., Alloy, L.B. & Whitehouse, W.G. Expanded Hopelessness Theory of Depression: On the Mechanisms by which Social Support Protects Against Depression. Cogn Ther Res 30, 307–333 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9048-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9048-3