Abstract

Recent genome-wide association (GWA) studies identified several common variants for obesity: rs9939609 in FTO, rs7566605 near INSIG2 and both rs17782313 and rs17700633 near the MC4R gene. This study aimed to assess the influence of these polymorphisms on development of adiposity in European– (EA) and African–American (AA) youth in two ongoing longitudinal studies including 986 and 606 participants with age ranges of 10–25.8 and 4.0–23.9 years, respectively. Individual growth curve modeling was conducted separately in the two studies. We tested the effect of the SNPs on levels and increase with age (i.e., slope) of weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference and skinfolds from childhood to adulthood, and potential moderation by ethnicity or gender. Beta coefficients computed in the two studies were pooled using meta-analysis. Rs9939609 was associated with logtransformed levels of BMI (β = 0.021, P = 0.01), weight (β = 0.019, P = 0.04) and waist circumference (β = 0.012, P = 0.04). Rs17782313 was associated with triceps (β = 0.05, P = 0.02). Significant interactions of rs17700633 with gender were observed on subscapular-, suprailiac- and sum of skinfolds, with significant associations limited to males (P < 0.05). No significant interactions with ethnicity were found. Only one effect on the slope was observed, rs17700633 showed a significant interaction with age on triceps (β = 0.004, P = 0.04). In two longitudinal studies of EA and AA youth, we replicated the effect of FTO and common variants near MC4R on general and central adiposity. These variants did not affect the increase with age of adiposity from childhood to adulthood with one exception. Common variants for obesity identified in GWA studies have detectable but modest effects on growth curves for adiposity in EA and AA youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is becoming an increasingly important clinical and public health challenge worldwide and is associated with several comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome and certain forms of cancer [1–3]. The complex etiology of obesity reflects effects of genes and environment as well as their interactions [4]. In this context, an understanding of the effects of environment and genes on obesity and also their interactions is important to provide a basis for determining the role they could have on the development and prevention of obesity.

In recent years, several independent genome-wide association (GWA) studies reported significant associations of common genetic variants near INSIG2(rs7566605) [5], in the FTO gene (rs9939609) [6–9] and near MC4R (rs17782313, rs17700633) [10] with body mass index (BMI) as a measure of general adiposity and for MC4R rs12970134 with waist circumference as a measure of central adiposity [11]. Associations of FTO and obesity have been broadly replicated in various populations including Caucasians, Asians and African–American children [7, 8, 12, 13], but could not be confirmed in an African population [14]. Similarly, the association of the common variants near MC4R with obesity were replicated in Caucasians [15–19], but two recent studies showed inconsistent findings in African–Americans [15, 19]. In contrast, the association of the common variant near INSIG2 has not been consistently replicated [20, 21].

The rise of overweight and obesity in youth is of particular concern in the current obesity epidemic. Many overweight and obese children go on to become obese adults [22] and are at greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome [1, 2]. Thus greater insight into the development of adiposity from childhood into adulthood is needed. However, most of the above mentioned studies were cross-sectional and do not offer information on the impact of genetic susceptibility on interindividual differences in development of obesity over time. To the best of our knowledge, the few available longitudinal studies [16, 23–25] have not investigated the influence of these common variants on growth curves for adiposity from childhood to adulthood, nor did they study the interaction of these common variants with ethnicity or gender.

The main purpose of the current study was to assess the effect of these common variants in FTO, near INSIG2 and near MC4R on longitudinal development of general and central obesity from childhood to early adulthood in European–American (EA) and African–American (AA) youth available from the Georgia Cardiovascular (CV) Twin study [26] and the Blood Pressure (BP) Stress Cohort study [27, 28]. We further investigated whether the effects of these common variants on general and central obesity were moderated by ethnicity or gender.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Subjects are among participants in two ongoing longitudinal studies, the Georgia CV Twin study [26] [(n = 986 twins, with 480 monozygotic (MZ) (234 pairs and 12 singleton) and 506 dizygotic (DZ) twins (230 pairs and 46 singletons)) and the BP Stress study [27, 29] (n = 606, including 135 siblings). The twin longitudinal data encompass 4 assessments (ranged from 2 to 4) over a 13-year period (1996–2009). All twins were recruited from public middle and high schools in the Augusta, Georgia area and the cohort consisted of roughly equal numbers of AAs and EAs (56.5% EA, 47.9% male, mean age at entry [SD]: 14.3[2.7] years, ranged from 10.0 to 25.8 years). All twin pairs were reared together and zygosity was determined by genotyping 5 standard microsatellite markers using buccal swabs or buffy coat DNA [30]. The BP Stress study consisted of approximately equal numbers of EA and AA boys and girls (50.7% EA, 49.3% male, mean age at entry [SD]: 11.9[4.0], ranged from 4.0 to 23.9 years). The BP Stress study is an ongoing longitudinal study of the development of cardiovascular risk factors in which evaluations have been conducted annually from 1989 to 2007 encompassing up to 16 assessments (ranged 2–16). Information on subject recruitment, evaluation that started in 1989 and attrition rate have been previously described [29, 31]. The criteria for classifying subjects as AAs or EAs using self-identification of ethnicity have been described previously [32]. Subjects were apparently healthy, free of any acute or chronic illness on the basis of parental reports and were taking no medication that could influence the results. The Institutional Review Board at the Medical College of Georgia approved the studies. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and by parents if subjects were <18 years of age.

The data sets are complicated because not all subjects had the same number of visits, with subjects recruited into the two studies at different ages and different years. In the current study, only subjects with at least 2 visits were included because the analyses depend on fitting polynomial regression curves to each subject’s data. In the Georgia CV Twin study 65.2% of subjects had ≥3 visits, and in the BP Stress study 99.8% of subjects had ≥3 visits and 93.7% had ≥8 visits, making the data set very informative for the study of obesity changes over time. The annualized attrition rate has been <6%/year in the Georgia CV Twin study and <4%/year in the BP stress study, which has been primarily due to some of the subject moving out of the region. There have been no significant differences in age, ethnicity, or sex distributions between the dropouts and the subjects that remained in the study.

Anthropometrics assessment

Height and weight were measured by standard methods using a wall-mounted stadiometer and a digital scale, respectively. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Waist circumference (in cm) was measured twice at the center of the umbilicus over the T-shirt and the values were averaged. Skinfold thicknesses (i.e., triceps, subscapular, and suprailiac) were measured on the right side of the body with Lange calipers according to established protocols [33]. Three sets of measurements for each skinfold were recorded and averaged. The inter-correlations were >99%. BMI and the sum of the 3 skinfold thicknesses were used as measures of general adiposity, while waist circumference was used as a measure of central adiposity.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from buffy coats by using the QiaAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or from buccal swabs by using QuickExtract DNA Extraction Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI). The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs7566605, rs9939609, rs17782313 and rs17700633 were genotyped by allelic discrimination Taqman assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR were performed in a 96-well format in a total of 5 μl reaction volume using 10 ng of genomic DNA and FAM/VIC dye labeled allelic probes with the Taqman Universal Fast Master mix and subjected to 95°C for 15 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min on an ABI 9800 Fast Thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The Taqman assay plates were transferred to an ABI 7500 Fast Real Time PCR system in which the fluorescence intensity in each well of the plate was recorded and genotypes were analyzed using Sequence Detection Software 1.3(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Genotyping quality control procedures included genotyping 10% duplicates for accuracy checking and inclusion of both positive and non-template controls in each 96-well plate. Genotyping success rates were 99.5% for rs7566605, 99.5% for rs9939609, 97% for rs17700633 and 93% for rs17782313. Genotyping accuracy for the four SNPs, as determined by concordance between duplicates, was 100%.

Social economic status

Social economic status (SES) was represented by father’s education level divided into three categories: low education level (<12 years), medium education level (≥12 and <16 years) and high education level (≥16 years) [28]. As no significant interaction for any of the SNPs with SES on any of the adiposity variables was found (data not shown), and SES was not a covariate of interest in the current study, we did not include SES in the final models.

Statistical analysis

Growth curve modeling

All analyses in this study were conducted by using individual growth curve modeling within a multilevel framework, which is a data analysis technique especially designed for longitudinal data [27, 34]. In growth curve modeling, a curve is fitted for each individual subject. These individual growth curves in adiposity are characterized by their intercept (or level) and slope (rate of change). Addition of independent variables to the model, such as SNPs, aimed at explaining between-subject variation (in level and slope) of the growth curves.

Analytical strategy and software

There were 3 levels in our multilevel longitudinal data, repeated measures of the same subjects at level 1, within family (twins or sibs) at level 2 and between families at level 3. First, we started with the intercept-only model to test the random effect of intercept within families (level 2) and between families (level 3); furthermore, in the Georgia CV Twin study, we modeled MZ and DZ covariances separately to account for the different degrees of relatedness between MZ and DZ twin pairs [35]. Second, the effects of age and age2 were modeled, i.e., linear (fixed and random) and quadratic trends (fixed).We did not fit the random quadratic term as the models were not robust. A likelihood ratio test was used to select the best-fitting model at a significance level of P < 0.05. Third, age at entry, ethnicity and gender were separately added to the growth curve model to test its effect on adiposity intercept. We further tested the effects of gender and ethnicity on the rate of change in adiposity modeled as interactions with age and age2, as described in detail previously [27, 29]. The interaction between ethnicity and gender was tested as well. Finally, after arriving at the most parsimonious full “environmental” model including only significant terms (shown in Supplementary Table 1), SNPs were added to the model to test their main effects on the level of the growth curve. Based on the previous findings [10, 36], we only considered an additive model in testing the associations between these SNPs and adiposity phenotypes except for the SNP near INSIG2 for which we used a recessive model [5]. Effects on the slope of adiposity growth curve were modeled as interactions of SNPs with age. Analyses were done separately for each of the SNPs and followed with the test of SNP interaction with ethnicity and gender. Interactions of SNPs with ethnicity and gender were modeled to examine whether the effect of the SNP on adiposity was moderated by these factors. A likelihood ratio test was used to determine the significance of the effects that were added to the model in each of the analysis steps at a significance level of P < 0.05.

There were several distinct characteristics between the two longitudinal studies. For example, subjects were twins with a maximum of 4 visits in the Georgia CV Twin study, while <25% of subjects were sibs in the BP Stress study, and the follow-up period was much longer with up to 16 visits. Thus, the growth curve modeling was conducted in the Georgia CV Twin study and the BP Stress study separately, and β coefficients computed in the two studies were pooled in meta-analysis using the inverse variance-weighted method [37], the I 2 statistic,which describes the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, was used to estimate between-study heterogeneity (P > 0.1) [38]. If there is very little variation between studies then I 2 will be low and a fixed effects model might be appropriate. Meta-analysis was performed using Stata 10 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

In the analyses, all variables except height were natural log transformed to obtain better approximations of the normal distribution. We only assessed the influence of MC4R rs17782313 on height based on Loos et al.’s findings [10]. In the Georgia CV Twin study and the BP Stress study, age was expressed as a deviation from the mean age of 17.5 and 18.2 years, respectively; and age at entry was centered at the mean age of 14.3 and 11.9 years at the first visit, respectively.

All multilevel modeling was performed using mixed linear models in Proc Mixed of the SAS/Stat software package (Release 9.1, 2002, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), which is robust to and appropriately handles unbalanced longitudinal data. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and ethnic differences in allele and genotype frequencies were tested by a χ2 test in only one member per family, which was chosen randomly to prevent inflated significance. Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the two MC4R SNPs was tested by calculating D′ as well as r 2 for AAs and EAs separately.

Results

Participant characteristics

Descriptive characteristics by ethnicity and gender at first visit of subjects with available genotype and phenotype are shown separately for the Georgia CV Twin and BP Stress studies in Table 1. Effects of ethnicity, gender and their interaction were tested using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with age as covariate. The mean age at first visit was 14.3 and 11.9 years in the Georgia CV Twin and BP Stress study, respectively. Many significant gender differences were observed, although some of these were limited to the EA group. Similarly, many significant ethnic differences were observed with some limited to females, as indicated in Table 1. The correlations between adiposity measures at the first visit in the two cohorts are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Allele and genotype frequencies

All variants were common in both ethnic groups with minor allele frequency (MAF) from 20.9 to 52.1%. As indicated in Table 2, there were significant differences in genotype and allele frequencies of rs9939609 in FTO gene, rs17782313 near MC4R gene between EA and AA subjects in both studies, but not for INSIG2 rs7566605 and MC4R rs17700633 (Table 2).

Furthermore, rs17782313 and rs17700633 near MC4R gene were not found to be in strong LD in both studies (D′ = 0.178, r 2 = 0.027 for EAs, D′ = 0.378, r 2 = 0.10 for AAs in the Georgia CV Twin study; D′ = 0.157, r 2 = 0.023 for EAs, D′ = 0.505, r 2 = 0.14 for AAs in the BP Stress study). All variants were in HWE in both ethnic groups except for rs9939609 in the AA group of the BP Stress study (Table 2).

Results of growth curve modeling analysis of common variants on adiposity-related phenotype levels

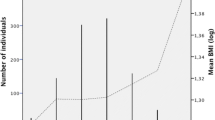

Supplementary Table 3 displays the results for the analysis of single locus effects on adiposity-related phenotype levels in the Georgia CV Twin and BP Stress studies separately based on the most parsimonious full “environmental” models (Supplementary Table 1) as well as the results of the meta-analysis. In the meta-analysis, we found that each copy of the FTO rs9939609 C allele was significantly associated with BMI (increasing with 2.1% per allele, P = 0.01), weight (increasing with 1.9% per allele, P = 0.04), as well as with waist circumference (increasing with 1.2% per allele, P = 0.04) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 3). Figure 2 clearly shows the effect of FTO rs9939609 on the level of BMI in the Georgia CV Twin study (P for level = 0.02). Compared with the full environmental model, the additional explained percentages of variance were 0.31, 0.14 and 0.16% for BMI, weigh and waist circumference, respectively.

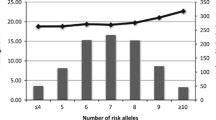

In the meta-analysis, significant associations were found between MC4R rs17782313 and triceps skinfold level (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 3), increasing with 5.0% per allele (P = 0.02) and 0.25% explained variance. We also found a borderline significant association between rs17782313 and sum of skinfolds level (P = 0.08), increasing with 3.7% per allele and 0.16% explained variance. Moreover, we observed the C allele at rs17782313 was negatively associated with height (P = 0.03) (Supplementary Table 3).

Significant interactions of MC4R rs17700633 with gender on subscapular, suprailiac and sum of skinfolds were observed (P inter = 0.01, 0.04 and 0.03, respectively) (Supplementary Table 4). We found this locus showed a significant effect in males only, with the A allele carriers having significantly higher skinfolds levels, increasing with 6.0, 6.3 and 6.3% per allele on subscapular, suprailiac and sum of skinfolds levels, respectively(Supplementary Table 3). Compared with the full environmental model, the locus explained additional 0.44, 0.35 and 0.44% between-subjects variation of triceps, subscapular and sum of skinfolds in males, respectively. Significant interactions of MC4R rs17700633 and rs17782313 with gender on weight were also observed (both P = 0.002). However, stratified analysis showed no significant effect on weight level in either gender group (Supplementary Table 3).

No significant associations were observed between rs7566605 near the INSIG2 gene and any of the adiposity-related phenotypes (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3).

No significant interactions between these SNPs and ethnicity were observed for any of the adiposity-related phenotypes (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Table 5).

The growth curve modeling analysis of common variants and adiposity levels in EAs and AAs separately showed that rs9939609 was significantly associated with BMI, waist circumference and sum of skinfolds in EAs, but no significant associations were found in AAs. However, most of the effects were in the same direction (Supplementary Table 6).

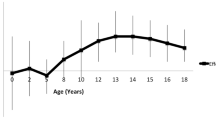

Results of growth curve modeling analysis of common variants on increases with age (slope) of adiposity-related phenotype

None of the 4 SNPs showed significant interactions with age on any of the adiposity-related phenotypes (Supplementary Table 7), with one exception. MC4R rs17700633 showed a significant interaction with age on triceps skinfold (P for slope = 0.04). Figure 4 shows growth curves for triceps skinfold for the three genotype groups of rs17700633 in the BP Stress study (P for slope = 0.03), clearly indicating an increasing effect of genotype over time. For example, the per A-allele effect size was ~−0.03 mm at 15 years and ~0.88 mm at 25 years.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the role of common variants in FTO and near the INSIG2 and MC4R loci identified through GWA studies on development of obesity from childhood to adulthood. We performed growth curve modeling in 1592 EA and AA youth from two longitudinal studies separately, and pooled results through meta-analysis. There were five main findings in this study. The first was that we replicated the effect of FTO rs9939609 on levels of BMI (increasing with 2.1% per A-allele), weight (increasing with 1.9% per A-allele) and waist circumference (increasing with 1.2% per A-allele) in the meta-analysis with explained variances of 0.31, 0.14 and 0.16, respectively. The second was that MC4R rs17782313 was significantly associated with triceps skinfold (increasing with 5.0% per C-allele). The third was that no significant interaction between any of the SNPs and ethnicity on any of the adiposity-related phenotype was observed. The fourth was that significant interactions between MC4R rs17700633 and gender on the level of subscapular, suprailiac skinfold and sum of skinfolds were observed. Finally, a significant effect of MC4R rs17700633 on increase of triceps skinfolds with age (i.e., slope) was observed.

Since Frayling et al. [9] first reported the significant associations between the FTO variant rs9939609 and obesity-related phenotypes such as BMI, weight, waist circumference, %BF and skinfolds in both children and adults, these associations have been replicated in Europeans [7, 8, 24, 25, 39] and Asians [12] through both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. In our longitudinal studies, we found that each copy of the FTO rs9939609 A allele was significantly associated with BMI with 2.1% increase per allele. For example, within a population with average BMI of 25 kg/m2, the approximate per A-allele effect is ~0.5 kg/m2, which is similar to the effect that Frayling reported in UK children at the age of 11 years (0.4 kg/m2) and a little higher than that in Finnish children at the age of 14 years (0.1 kg/m2) [9]. A cross-sectional sample of 1,600 subjects has 80% power at an alpha of 0.05 to detect an effect size of the SNP of 0.5% of the trait variance. Thus, our meta-analysis of two cohorts with repeated measures will have had sufficient power to detect even smaller effects. We found that the variance in BMI explained by rs9939609 was 0.31%, which is lower than the previously reported ~1.0% and probably due to sample variability [9]. In addition, we replicated the association of FTO rs9939609 with weight and waist circumference, which is consistent with Frayling et al.’s findings [9]. The effect of FTO rs9939609 on sum of skinfolds did not reach significance. This could be due to a more inaccurate measurement procedure compared to BMI, or that the measures represent slightly different aspects of adiposity. Furthermore, several longitudinal studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of rs9939609 on the development of obesity over time [24, 25, 40]. However, the results of the rs9939609 by age interaction were inconsistent. In the MRC National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) cohort, a longitudinal birth cohort from 1946 and followed through to age 53 years, significant genotype-by-age interaction was observed for BMI, showing the association strengthened between age 2 and 20 years at a rate of 0.007 sex-specific standard deviation scores (SDS) (95% CI 0.003–0.01) per A-allele per year, reached a peak at age 20 years, and thereafter weakened with age from 20 to 53 years (rate of decline: −0.003SDS per A-allele per year). And similar pattern was observed for weight [40]. An increasing effect of genotype over time (P = 0.047) was observed in 1886 middle-aged females from the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey (CLHNS) cohort [25] with a maximum of 8 measurements spanning 22 years. However, the interaction between rs9939609 and age was not significant in either a female cohort of about 2,200 nurses followed up from 1976 to 2002 (average age at entry: 44 years) or a male cohort of about 3,500 Health professional followed up from 1986 to 2002 (average age at entry: 56 years) (P = 0.08 and 0.20, respectively) [24], although in the male cohort the genetic effects appeared to decrease at older age. In our longitudinal study in youth, we did not find any significant interaction between rs9939609 and age for any of the obesity-related phenotypes. That is, rs9939609 did not affect the slope of the growth curves of these traits. Although the association between rs9939609 and adiposity has been broadly replicated in Europeans [7, 8, 24, 39] and Asians [12], it could not be confirmed in an African population [14]. In our study including both EA and AA youth, we did not find any significant interaction between rs9939609 and ethnicity on any adiposity-related phenotype. We also did not find any significant interaction between rs9939609 and gender, which was consistent with Hardy et al.’s finding of no differences between males and females in the genetic associations with body size across the life course [40].

Since Loos et al. [10] reported association between common variants near MC4R and fat mass, weight and BMI in both children and adults, several studies have replicated the finding in European populations [15–18]. In our longitudinal studies, we found the C allele carriers of rs17782313 showed higher weight, BMI and waist circumference compared to TT homozygotes, but the association did not reach statistical significance. However, we did find a significant effect of rs17782313 on triceps skinfolds level, and a borderline significant effect of rs177882313 on sum of skinfolds. The C allele at rs177882313 was found to be positively associated with height in European adults [10, 17]. On the contrary, we found rs17782313 was negatively associated with height in youth, and stratified analysis showed significant negative association only in AAs (β = −0.9, P = 0.035). Loos et al. [10] also found the per-C allele effect of rs17782313 on BMI in children was about twice that observed in adults. In the NSHD cohort, significant genotype-by-age interaction was observed for weight, showing the association strengthened between birth and 20 years at a rate of 0.005 SDS (95% CI 0.001–0.008) per C-allele per year, reached a peak at age 20 years, and thereafter weakened with age (rate of decline: −0.002SDS per C-allele per year) [40]. However, no significant genotype-by-age interaction was observed for BMI in the NSHD cohort [40]. In our longitudinal study, we did not find significant interaction between rs17782313 and age on any of the obesity-related phenotypes, which is in line with findings for BMI in the NSHD cohort [40]. A recent paper could not replicate the association of the common variants near MC4R and obesity in African-Americans [15]. In the current study including both EAs and AAs, we did not find any significant interaction between rs17782313 and ethnicity on any of these obesity-traits. Findings on the interaction between rs17782313 and gender on adiposity in previous studies are inconsistent [40–42]. In 3885 Swedish adults, rs17782313 showed significant interaction with gender (P inter = 0.02), with the association limited to females (P = 0.003) [42]. On the contrary, a study in French adults found stronger association of rs17782313 with adiposity and fat mass deposition in males than in females (P = 0.003 and 0.03, respectively) [41]. In the NSHD cohort, no significant interaction between rs17782313 and gender for adiposity phenotypes was observed (P > 0.05) [40]. In our study, rs17782313 significantly interacted with gender on weight, and the stratified analyses showed that neither of the associations was significant. Further investigations are needed to ultimately clarify whether the effect of rs17782313 on obesity is modified by gender.

Loos et al. [10] found that the association between rs17700633 and BMI seemed to be dependent on that of rs17782313. We did not observe any significant association between rs17700633 and weight, BMI or waist circumference, which is inconsistent with findings in a middle aged Danish population [17]. We found significant interaction between rs17700633 and age on triceps skinfolds, which means rs17700633 affected the slope of the triceps growth curve. The A allele carriers showed a steeper increase in triceps skinfold per unit increase of age as compared to the GG homozygotes. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this significant interaction is a chance finding. We observed significant interaction between rs17700633 and gender for subscapular, suprailiac and sum of skinfolds, with significant associations limited to males. These findings indicate that the effect of rs17700633 on skinfolds might be modified by gender.

The association of INSIG2 rs7566605 with BMI [5], has not been consistently replicated [20, 21]. In our study, we did not find any significant association between rs7566605 and any obesity-related phenotype levels, nor did we find any significant interaction with ethnicity, gender or age.

A major strength of our study is the longitudinal design of both cohorts with up to 16 assessments in one of these. Longitudinal studies offer information on determinants of interindividual differences in the development of obesity over time. These two cohorts thus allowed us to investigate the influence of common genetic variants in growth curve modeling to obtain better insight into the development of obesity from childhood into adulthood. Longitudinal designs have superior power to detect genetic effects on the trait levels compared to cross-sectional studies, because measurement of subjects at multiple time points provides much better precision in determining the phenotypes [43, 44]. As such, longitudinal studies such as this one require a fraction of the sample size of cross-sectional studies to achieve the same power. Another strength is the involvement of AA as well as EA youth, and the investigation of a potential interaction of these common variants with ethnicity. Several limitations of our study need to be mentioned as well. In these two studies, we used BMI and skinfolds as measures of general adiposity and waist circumference as a measure of central adiposity, which are convenient and low cost measurements, while more accurate measurements of percent body fat for general adiposity and visceral adipose tissue for visceral adiposity were not available. In these two studies, sexual maturation was not assessed, thus it could not be incorporated as a covariate.

In summary, in two longitudinal studies of EA and AA youth, we replicated the effect of FTO and common variants near MC4R on general and central adiposity. These effects were similar for EAs and AAs. Furthermore, these common variants did not affect the slope of adiposity development from childhood to adulthood with one exception. Common variants for obesity identified in genome-wide association studies have detectable but modest effects on growth curves for adiposity in African– and European–American youth.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

African–American

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DZ:

-

Dizygotic

- EA:

-

Europe-American

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equations

- Georgia CV:

-

Georgia cardiovascular

- GWA:

-

Genome-wide association

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequencies

- MZ:

-

Monozygotic

- SES:

-

Social economic status

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

Deckelbaum RJ, Williams CL. Childhood obesity: the health issue. Obes Res. 2001;9(Suppl 4):239S–43S.

Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Jama. 2003;289(1):76–9.

Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–78.

Loos RJ, Bouchard C. Obesity—is it a genetic disorder? J Intern Med. 2003;254(5):401–25.

Herbert A, Gerry NP, McQueen MB, Heid IM, Pfeufer A, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Meitinger T, Hunter D, Hu FB, et al. A common genetic variant is associated with adult and childhood obesity. Science (New York, NY). 2006;312(5771):279–83.

Hinney A, Nguyen TT, Scherag A, Friedel S, Bronner G, Muller TD, Grallert H, Illig T, Wichmann HE, Rief W, et al. Genome Wide Association (GWA) Study for early onset extreme obesity supports the role of fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) variants. PloS one. 2007;2(12):e1361.

Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, Najjar S, Nagaraja R, Orru M, Usala G, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(7):e115.

Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, Durand E, Korner A, Jacobson P, Carlsson LM, Kiess W, Vatin V, Lecoeur C, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39(6):724–6.

Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Perry JR, Elliott KS, Lango H, Rayner NW, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science (New York, NY). 2007;316(5826):889–94.

Loos RJ, Lindgren CM, Li S, Wheeler E, Zhao JH, Prokopenko I, Inouye M, Freathy RM, Attwood AP, Beckmann JS, et al. Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):768–75.

Chambers JC, Elliott P, Zabaneh D, Zhang W, Li Y, Froguel P, Balding D, Scott J, Kooner JS. Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2008;40(6):716–8.

Chang YC, Liu PH, Lee WJ, Chang TJ, Jiang YD, Li HY, Kuo SS, Lee KC, Chuang LM. Common variation in the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene confers risk of obesity and modulates BMI in the Chinese population. Diabetes. 2008;57(8):2245–52.

Grant SF, Li M, Bradfield JP, Kim CE, Annaiah K, Santa E, Glessner JT, Casalunovo T, Frackelton EC, Otieno FG, et al. Association analysis of the FTO gene with obesity in children of Caucasian and African ancestry reveals a common tagging SNP. PloS one. 2008;3(3):e1746.

Hennig BJ, Fulford AJ, Sirugo G, Rayco-Solon P, Hattersley AT, Frayling TM, Prentice AM. FTO gene variation and measures of body mass in an African population. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:21.

Grant SF, Bradfield JP, Zhang H, Wang K, Kim CE, Annaiah K, Santa E, Glessner JT, Thomas K, Garris M, et al. Investigation of the locus near MC4R with childhood obesity in Americans of European and African ancestry. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2009;17(7):1461–5.

Qi L, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Hu FB. The common obesity variant near MC4R gene is associated with higher intakes of total energy and dietary fat, weight change and diabetes risk in women. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(22):3502–8.

Zobel DP, Andreasen CH, Grarup N, Eiberg H, Sorensen TI, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Jorgensen T, Pedersen O, et al. Variants near MC4R are associated with obesity and influence obesity-related quantitative traits in a population of middle-aged people: studies of 14, 940 Danes. Diabetes. 2009;58(3):757–64.

Haupt A, Thamer C, Heni M, Tschritter O, Machann J, Schick F, Machicao F, Haring HU, Staiger H, Fritsche A. Impact of variation near MC4R on whole-body fat distribution, liver fat, and weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2009;17(10):1942–5.

Liu GF, Zhu HD, Lagou V, Gutin B, Barbeau P, Treiber FA, Dong YB, Snieder H: Variants near melanocortin 4 receptor are associated with general and visceral adiposity in European- and African–American Youth. J Pediatr. 2010.

Lyon HN, Emilsson V, Hinney A, Heid IM, Lasky-Su J, Zhu X, Thorleifsson G, Gunnarsdottir S, Walters GB, Thorsteinsdottir U, et al. The association of a SNP upstream of INSIG2 with body mass index is reproduced in several but not all cohorts. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(4):0627–0633.

Vimaleswaran KS, Franks PW, Brage S, Sardinha LB, Andersen LB, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U, Loos RJ. Absence of association between the INSIG2 gene polymorphism (rs7566605) and obesity in the European Youth Heart Study (EYHS). Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2009;17(7):1453–7.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–73.

Jess T, Zimmermann E, Kring SI, Berentzen T, Holst C, Toubro S, Astrup A, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Sorensen TI. Impact on weight dynamics and general growth of the common FTO rs9939609: a longitudinal Danish cohort study. Int J Obesity (2005). 2008;32(9):1388–94.

Qi L, Kang K, Zhang C, van Dam RM, Kraft P, Hunter D, Lee CH, Hu FB. Fat mass-and obesity-associated (FTO) gene variant is associated with obesity: longitudinal analyses in two cohort studies and functional test. Diabetes. 2008;57(11):3145–51.

Marvelle AF, Lange LA, Qin L, Adair LS, Mohlke KL. Association of FTO with obesity-related traits in the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey (CLHNS) Cohort. Diabetes. 2008;57(7):1987–91.

Ge D, Dong Y, Wang X, Treiber FA, Snieder H. The Georgia Cardiovascular Twin Study: influence of genetic predisposition and chronic stress on risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9(6):965–70.

Dekkers C, Treiber FA, Kapuku G, Van Den Oord EJ, Snieder H. Growth of left ventricular mass in African American and European American youth. Hypertension. 2002;39(5):943–51.

Podolsky RH, Barbeau P, Kang HS, Zhu H, Treiber FA, Snieder H. Candidate genes and growth curves for adiposity in African– and European–American youth. Int J Obesity (2005). 2007;31(10):1491–9.

Dekkers JC, Snieder H, Van Den Oord EJ, Treiber FA. Moderators of blood pressure development from childhood to adulthood: a 10-year longitudinal study. J Pediatr. 2002;141(6):770–9.

Jackson RW, Snieder H, Davis H, Treiber FA. Determination of twin zygosity: a comparison of DNA with various questionnaire indices. Twin Res. 2001;4(1):12–8.

Treiber FA, McCaffrey F, Musante L, Rhodes T, Davis H, Strong WB, Levy M. Ethnicity, family history of hypertension and patterns of hemodynamic reactivity in boys. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(1):70–7.

Snieder H, Dong Y, Barbeau P, Harshfield GA, Dalageogou C, Zhu H, Carter ND, Treiber FA. Beta2-adrenergic receptor gene and resting hemodynamics in European and African American youth. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(11):973–9.

Wright RA, Heymsfield S. Nutritional assessment. Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications, Inc.; 1984.

Willett JB, Singer JD, Martin NC. The design and analysis of longitudinal studies of development and psychopathology in context: statistical models and methodological recommendations. Dev Psychopathol. 1998;10(2):395–426.

Berg AI, Hoffman L, Hassing LB, McClearn GE, Johansson B. What matters, and what matters most, for change in life satisfaction in the oldest-old? A study over 6 years among individuals 80+. Aging Mental health. 2009;13(2):191–201.

Frayling TM. Genome-wide association studies provide new insights into type 2 diabetes aetiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(9):657–62.

Sutton AJ, Higgins JP. Recent developments in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2008;27(5):625–50.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin Res ed 2003). 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Do R, Bailey SD, Desbiens K, Belisle A, Montpetit A, Bouchard C, Perusse L, Vohl MC, Engert JC. Genetic variants of FTO influence adiposity, insulin sensitivity, leptin levels, and resting metabolic rate in the Quebec Family Study. Diabetes. 2008;57(4):1147–50.

Hardy R, Wills AK, Wong A, Elks CE, Wareham NJ, Loos RJ, Kuh D, Ong KK. Life course variations in the associations between FTO and MC4R gene variants and body size. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(3):545–52.

Cauchi S, Stutzmann F, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Durand E, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, Marre M, Vol S, Tammelin T, Laitinen J, et al. Combined effects of MC4R and FTO common genetic variants on obesity in European general populations. J Mol Med (Berlin, Germany). 2009;87(5):537–46.

Renstrom F, Payne F, Nordstrom A, Brito EC, Rolandsson O, Hallmans G, Barroso I, Nordstrom P, Franks PW. Replication and extension of genome-wide association study results for obesity in 4923 adults from northern Sweden. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(8):1489–96.

Phillips A. Commentary: Balancing quantity and quality when designing epidemiological studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):58–9.

Wong MY, Day NE, Luan JA, Chan KP, Wareham NJ. The detection of gene-environment interaction for continuous traits: should we deal with measurement error by bigger studies or better measurement? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):51–7.

Acknowledgments

The Georgia Cardiovascular Twin study was supported by NIH grant HL56622. The BP Stress study was supported in part by grants HL 69999 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and a State of Georgia Biomedical Initiative grant to the Georgia Center for the Prevention of Obesity and Related Disorders (GCORD). We also want to thank Ilja Nolte (University Center Medical Groningen, The Netherlands) and Lesa Hoffman (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA) for their help on the statistical methodology.

Conflict of interest

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationship to this article to disclose. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Zhu, H., Dong, Y. et al. Influence of common variants in FTO and near INSIG2 and MC4R on growth curves for adiposity in African– and European–American youth. Eur J Epidemiol 26, 463–473 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9583-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9583-4