Abstract

Expanding our knowledge on parenting practices of immigrant families is crucial for designing culturally sensitive parenting intervention programs in countries with high immigration rates. We investigated differences in patterns of parenting between second-generation immigrant and native families with young children. Authoritarian and authoritative control and sensitivity of second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers of 2-year-old children (n = 70) and native Dutch mothers (n = 70) were observed in the home and in the laboratory. Controlling for maternal age and education, Turkish immigrant mothers were less supportive, gave less clear instructions to their children, were more intrusive and were less authoritative in their control strategies than native Dutch mothers. No differences were found in authoritarian control. In both ethnic groups supportive presence, clarity of instruction, authoritative control, and low intrusiveness loaded on one factor. No differences between ethnic groups were found in gender-differentiated parenting. Maternal emotional connectedness to the Turkish culture was associated with less authoritative control, whereas more use of the Turkish language was related to more sensitivity. Even though mean level differences in parenting behaviors still exist between second-generation Turkish immigrant and native Dutch mothers, the patterns of associations between parenting behaviors were comparable for both groups. This suggests that existing parenting interventions for native families may be applicable to second-generation Turkish immigrants as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An important aspect of parenting in the early years is the regulation of young children’s emotions and behaviors. Externalizing behaviors such as aggression emerge in the second year of life (Alink et al. 2006; Tremblay et al. 1999). In most cases, these behaviors decrease in the fourth year of life, but in others externalizing behaviors remain into later childhood and even adulthood (Campbell 1995; Loeber and Hay 1997). Early-onset externalizing problems have been found to predict subsequent psychopathology, and problems in several domains of functioning, including personal, social, and academic development (Campbell 1995). Parenting behaviors during early childhood that are related to child externalizing problems are sensitivity and control. These parenting behaviors are main features in two theoretical frameworks: attachment theory and coercion theory.

Attachment theory (Bowlby 1969) focuses on the quality of early parental care, in terms of parental sensitivity, as an important contributor to socialization processes in the first few years of life (Ainsworth et al. 1978). Parental sensitivity refers to the ability to perceive the child’s signals, to interpret these signals correctly, and to respond to them in a prompt and appropriate way (Ainsworth et al. 1978). The sensitivity construct is also closely related to measures of maternal warmth and emotional supportiveness (De Wolff and Van IJzendoorn 1997). Sensitive and warm parenting during early childhood predicts a secure parent–child relationship which in turn is associated with positive child development, such as social competence (e.g., Raikes and Thompson 2008; Sroufe et al. 2005). In contrast, insensitive parenting and a lack of warmth are associated with negative child development, for example externalizing behaviors (e.g., Belsky et al. 1996; Olson et al. 2000).

Coercion theory focuses on ineffective parental control (Patterson 1982). Parental control refers to how rules and limits are imposed on the child (for a review, see Coie and Dodge 1998) and is often distinguished as authoritarian versus authoritative control. Both authoritarian and authoritative parents expect their children to behave appropriately and to obey rules, but authoritarian parents restrict unwanted behavior without explanation by demanding and physical interference, whereas authoritative parents emphasize discussion, explanation, and clear communication (Baumrind 1966). More authoritarian and less authoritative control is associated with negative child outcomes, such as aggression (e.g., Patterson 1982; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994). According to the coercion theory coercive (i.e., authoritarian and non-authoritative) disciplinary interchanges between parents and children are likely to escalate child externalizing behavior in the short-term and to increase the likelihood of this behavior becoming stable (Snyder and Patterson 1995).

In more ‘collectivistic’ cultures (e.g., Turkish culture) interdependence is emphasized and the inhibition of the expression of the individual’s own wants and needs, and attention to the needs of others is valued (Markus and Kitayama 1991). In order to achieve these outcomes parents have been reported to be more authoritarian, using more restraining behaviors during social play, and expecting more obedience (Ispa et al. 2004; Rubin 1998). In Turkey, more obedience and dependence is expected from daughters than from sons, leading to more external control on girls compared to boys (Kağıtçıbaşı 2007). In more ‘individualistic’ cultures (e.g., Dutch culture), self-interest, autonomy, and self-reliance are more valued in the socialization process. Parents from these cultures tend to be more authoritative; they are supposed to try to promote independence, self-reliance, exploration of the environment, and put less emphasis on obedience and sociability (Harwood et al. 1995; Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2007). In the four-fold classification by Maccoby and Martin (1983), authoritarian parenting consists of high control combined with low warmth and acceptance. However, in collectivistic cultures authoritarian parents who demand obedience and are restrictive may not necessarily be rejecting or lacking in warmth (e.g., Deković et al. 2006; Rudey and Grusec 2001, 2006). In collectivistic cultures, authoritarian parenting goals (obedience, respect for adults) are more normative and may not necessarily reflect lack of warmth. For example, perceived higher parental control was not associated with lower warmth in Turkish immigrant families in Belgium (Güngör and Bornstein 2008).

When individuals migrate from collectivistic to individualistic countries they undergo an acculturation process (Berry et al. 2002), which can be a difficult process. When the cultural distance between the country of origin (e.g., collectivistic) and the country of settlement (e.g., individualistic) is large more behavioral changes (for example in parenting behaviors) are expected from immigrants (Ward 1996). Berry (1997) formulated an acculturation model in which the first dimension consists of a preference for maintaining one’s own heritage culture and ethnic identity (i.e., Turkish culture), and the second dimension is the preference to participate in the host society (i.e., the Netherlands). Second-generation immigrants did not experience migration themselves, but they are exposed to living in two cultures, with consequences for their adaptation in general and their parenting behaviors in particular. Depending on their acculturation level, their parenting behaviors may differ from those in their home country as well as from those in their resident country. Immigrant parents who are oriented to the cultural values of the host country more often adopt child-rearing attitudes and behaviors similar to the host society (e.g., Jain and Belsky 1997; Yağmurlu and Sanson 2009). For example, a study on acculturation and parenting values and practices in a sample of Turkish migrants living in Australia showed that mothers who were more willing to interact with the host culture favored more use of inductive discipline methods and child-centered goals that were more similar to the host society than mothers who favored separation from Australian society (Yağmurlu and Sanson 2009). However, other studies have also shown that (Turkish) immigrants tend to maintain the family values and parenting practices of their heritage culture (e.g., Bornstein and Cote 2001; Güngör and Bornstein 2008) and pass them on to the next generations (Phalet and Schönpflug 2001). A study among first- and second-generation Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands showed that adaptation to the host society was favored with respect to social contact with Dutch people and the Dutch language (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2003), but cultural maintenance was preferred regarding child-rearing and cultural habits.

The Turkish group is the largest immigration population in Europe (Crul 2008) as well as in the Netherlands (370,000; CBS 2008). The current study focuses on the second-generation of Turkish immigrants because the growth of the number of Turkish inhabitants is mostly due to the increase of the second-generation population. In addition, most Turkish immigrant families with young children have (at least one) second-generation parent. Investigating their parenting behaviors is important as they may be influenced by the collectivistic values of their own parents, but also by the values in the individualistic society they have lived in all their lives. Only a few studies have reported on parenting of young children in Turkish immigrant families in the Netherlands, but none focused exclusively on the second-generation, despite the increase of this group in the Netherlands and elsewhere, such as Germany (SCP 2006).

In one of the few studies on Turkish immigrant families in the Netherlands, maternal sensitivity during observations of problem solving tasks was lower in the Turkish immigrant families with 3 and 4-year-old children than in Dutch native families, when controlled for socio-economic status (Leseman and Van den Boom 1999). However, another study among mostly first-generation Turkish immigrant and Dutch families with children between the ages of 0 and 19 years showed no differences between the groups on self-reported responsiveness and expression of affection (Pels et al. 2006). With regard to discipline, authoritarian control was more common among (Turkish) immigrants than among native Dutch families, whereas differences in authoritative control were less evident (Pels et al. 2006). In another study, Turkish immigrant parents of 17-year-olds were less authoritative in their parenting practices than their Dutch counterparts (Van der Veen and Meijnen 2002). Regarding gender-differentiated parenting, girls and boys were treated equally in Turkish immigrant families (Çıtlak et al. 2008; Wissink et al. 2006). Importantly, since these studies have been conducted primarily among first-generation Turkish immigrant mothers in the Netherlands, it is unclear how the parenting behaviors of second-generation Turkish immigrant parents compare to those in native Dutch families.

As interrelations between parenting behaviors can be quite different in families with collectivistic versus individualistic cultural backgrounds, we investigated in our study both maternal sensitivity and control. These dimensions of parenting were investigated in a group of second-generation Turkish immigrant and Dutch mothers with children who showed high levels of externalizing behaviors. We selected mothers of externalizing children since many studies have found that the absence of positive (e.g., maternal sensitivity) and the presence of negative (e.g., authoritarian control) parenting practices are related to child externalizing behaviors (e.g., Pettit and Bates 1989; Rothbaum and Weisz 1994). Parenting interventions aimed at reducing child externalizing problems therefore focus predominantly on these aspects of parenting. However, we do not know whether the nature and structure of parenting behaviors in parents of children with externalizing problems are the same in Turkish immigrant families with a collectivistic background as in Western families with an individualistic background. This knowledge is crucial to designing culturally-sensitive parenting interventions for children at risk for behavior problems. We therefore focused on families with children with high levels of externalizing behaviors to find out whether the same parenting patterns are applicable to Turkish immigrant families. Furthermore, by focusing exclusively on the second-generation, we could ensure the homogeneity of the sample and control for the confounding effects of ethnicity and migration. Based on the literature, we formulated the following hypotheses: (1) Turkish immigrant mothers show more intrusive and less sensitive parenting, and that they use more authoritarian and less authoritative control than Dutch mothers. (2) In Turkish immigrant families the association between authoritarian control and maternal sensitivity may be positive, as opposed to Dutch families. (3) No differences in parenting behaviors of Turkish immigrant mothers with regard to the gender of their toddlers. (4) Parenting behaviors of Turkish immigrant mothers who report higher levels of acculturation are expected to be more similar to those of Dutch mothers.

Method

Participants and Procedure

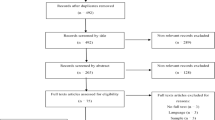

The Turkish Sample

Second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers of 2-year-old children were recruited from the municipal registers of several cities and towns in the western and middle region of the Netherlands. Only second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers born in the Netherlands (with at least one of their parents born in Turkey) with a 2-year-old child (age 22–29 months) were selected to ensure the homogeneity of the sample and to control for confounding effects of ethnicity and migration. We obtained 527 addresses of second-generation Turkish families. We sent these families an introduction letter and a brochure in which we informed the parents that the main researcher or a research assistant would come by to ask for their participation in this study. All correspondence was in the Turkish and the Dutch language. We could not reach 143 families, because 57 families had moved and 86 families were not at home when visited three different times at different days and hours to ask for their participation. Thus, in total, we reached 384 families of whom 230 (60%) participated in this study by filling out questionnaires on child behavior problems and parenting practices. One-hundred and fifty-four parents refused to participate. Unfortunately we were not able to collect any information on non-respondents. Only children for whom the primary parent was the mother were eligible for the study. Of the 230 participating families, 155 families also participated in a videotaped 1-hour home visit during which mothers and children performed several tasks. Eight families were excluded from the group due to serious medical condition in child or mother, physical or mental disability in child or mother, lack of fluency in the Turkish and Dutch language, or interfering factors during a home-visit which made coding of videotaped interactions impossible. This resulted in a sample of 147 Turkish children and their mothers. Because we wanted to look at the nature and structure of parenting in families with children showing externalizing problems, we selected for the current study children with scores ≥19 on the CBCL Syndrome Externalizing Problems (CBCL/1½-5; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) and their mothers. This resulted in a sample of 70 24-month-old Turkish children (M = 25.15, SD = 1.52, range = 22–29, 35 boys).

The Dutch Comparison Sample

The Dutch comparison sample for the current study is derived from the SCRIPT study (Screening and Intervention of Problem behavior in Toddlerhood). Addresses of participants were recruited from municipal registers of several cities and towns in the western region of the Netherlands. Dutch parents were sent a booklet by mail that included questionnaires on child behavior problems. Children with scores ≥19 on the CBCL Syndrome Externalizing Problems (CBCL/1½-5; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) and their mothers were invited to the university for observations of mother–child interactions in the laboratory. This resulted in a sample of 70 24-month-old Dutch children (M = 23.76, SD = 0.86, range = 22–26, 47 boys).

Measures

Internal consistencies of questionnaire data were assessed in the general Dutch (N = 175) and Turkish (N = 175) population screening samples of 2-year-olds (Yaman et al. 2009). The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1½-5) has previously been translated and validated in Turkish (Erol and Simsek 1997) and the Psychological Acculturation Scale has been used in the Netherlands and validated in research on immigrant groups (Stevens et al. 2004).

Externalizing behaviors

The most widely used questionnaire for the assessment of child behavior problems is the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA), which includes the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for different age groups, including two-year olds (e.g., Achenbach and Rescorla 2000). We preferred the CBCL because of the fact that this checklist is widely used, specifically tailored to assess behavior problems in young children, and is validated for both Turkish and Dutch children. The Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1½ to 5 (CBCL/1½-5; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000) was used to assess child externalizing behaviors. We used the Turkish translation (Erol and Şimsek 1997) and the Dutch translation (Koot et al. 1997) that have both been found to be valid and reliable. In the current study, the internal consistencies for Turkish and Dutch mother-reported CBCL were high for Externalizing Problems (.91/.90) and its subscales (Koot et al. 1997): Oppositional (.86/.88) and Aggressive (.78/.77). For the Overactive scale the internal consistency was acceptable for both groups with .66 and .61, respectively.

Maternal sensitivity

During three problem-solving tasks (a construction task, a sorting task, and a jigsaw puzzle) mothers’ sensitive responsiveness to her child was measured, each task lasting 5 min. These tasks were somewhat difficult for 2-year-old children and therefore mothers were instructed to help their children in a way they would normally do. The observations were rated with the Erickson scales to measure mothers’ Supportive presence, Intrusiveness, and Clarity of instruction on 7-point scales (Egeland et al. 1990; Erickson et al. 1985). Supportive presence refers to the mother’s expression of emotional support and positive regard by encouraging, giving support and confidence, reassuring and acknowledging the child’s accomplishments on the tasks. Intrusiveness refers to the mother’s lack of respect of the child’s autonomy when exploring or in problem solving situations, by interfering with the child’s needs, desires, interests, or behaviors. Clarity of instruction reflects the mother’s ability to give her child instructions and feedback in a usable form, to structure the situation so that the child knows what the nature and goals of the task are, without solving the task herself. Scale scores were computed by averaging the scores for the separate tasks.

The scales were coded by the first author and a PhD colleague, who were first trained by the second author (the expert) to code tapes from the Dutch sample (n = 20). The intraclass correlations (single rater, absolute agreement) for intercoder reliability between three pairs of coders ranged from .68 to .92 (M = 0.78). Then, 20 tapes from the Turkish sample were translated and transcribed in Dutch by the first author, who speaks both the Turkish and Dutch language fluently, for the reliability check of coding the Turkish sample (n = 20). The intraclass correlations (single rater, absolute agreement) for the Turkish sample were .71 for supportive presence, .76 for intrusiveness, and .71 for clarity of instruction. For the analyses, total maternal sensitivity was computed by summing the scores for supportive presence and clarity of instruction, and subtracting the score for maternal intrusiveness.

Maternal discipline

Specific maternal discipline strategies were observed during a 4-min clean-up task. After playing with attractive toys, the mother was asked to instruct her child to clean up the toys. The mother was allowed to help her child with three toys. We used the same event-based coding and adopted almost all of our coding categories, such as physical interference, commanding, positive feedback, and induction from the original coding procedure of Kuczynski et al. (1987), adding two additional categories, namely understanding and positive atmosphere. Maternal authoritative control (positive feedback, positive atmosphere, induction and understanding) and authoritarian control (commanding and physical interference) were observed. Positive feedback and creating a positive atmosphere involved giving compliments and making positive remarks when the child was cleaning up, and responding to what the child said (e.g., which toy wants to sleep in the basket?). Induction was coded when mothers explained why their child should not play further (even when this is not the real reason) and when mothers showed interest or were considerate of their child’s emotions when cleaning up the toys understanding was coded. Considering the negative discipline strategies, commanding was coded when mothers gave their child instructions to clean up in an authoritarian manner. When the mother used physical force to constrain the child from playing with the toys or to make the child clean up the toys, we coded this as physical interference. The number of times the mother had used a specific category was divided by the time of the episode and standardized to 3 min (see Alink et al. 2009).

All five coders (students with a Bachelor’s degree) spoke the Turkish and the Dutch language fluently and were blind to other data concerning the participants. First, a Dutch set was coded for intercoder reliability. Coders had a mean intraclass correlation (single rater, absolute agreement) with the expert of .80 for authoritative control (range = .71–.91, n = 25) and .76 for authoritarian control (range = .71–.86, n = 25). Then, the coders observed a Turkish set; the mean intraclass correlations (single rater, absolute agreement) for intercoder reliability (for all separate pairs of coders) were .84 (range = .74–.97, n = 20) for authoritative control and .88 (range = .75–.94, n = 20) for authoritarian control.

Acculturation

To measure the acculturation level of the mother, two components of acculturation were used, namely Turkish and Dutch language use (language acculturation) and psychological acculturation with regard to the Turkish and Dutch culture. With regard to language use Turkish immigrant mothers were asked how often they speak the Turkish and Dutch language with important others (their children, spouse, family members, and friends) (Van Oort et al. 2006). This scale consists of 12 items rated on a 5-point scale (ranging from 0, never, to 4, always/very often). The internal consistencies for the use of the Turkish and Dutch language were .81 and .75, respectively. Regarding the psychological acculturation of the mothers, the adapted version of the Psychological Acculturation Scale (PAS) was used (Stevens et al. 2004). Emotional connectedness of the mothers to the Turkish (six items) and the Dutch culture (six items) (e.g., I feel comfortable around Dutch/Turkish people) were rated on a 5-point scale (ranging from 0, totally disagree, to 4, totally agree). The internal consistencies for the emotional connectedness to the Turkish and Dutch culture were .83 and .79, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

The data showed one outlier for authoritarian control in the Dutch group and in the Turkish immigrant group, and one outlier for authoritative control in the Turkish immigrant group. When outliers (|z| > 3.29) were winsorized (i.e., “moved in close to the good data”, Hampel et al. 1986) by replacement of the outlying scores with the next highest value (with |z| < 3.29) in the distribution, the results were the same. One multivariate outlier in the Turkish immigrant group was removed from the analyses, because this mother did not speak at all with her child during the observations.

We used ANOVA to examine differences between the groups and correlation analysis to investigate relations between parenting behaviors in the Turkish immigrant and Dutch group. To investigate whether patterns of associations between parenting behaviors could be captured with similar models in the Turkish immigrant and Dutch group, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis, using the program EQS (Bentler 1989). We used multigroup analysis, which implies fitting a factor model to several groups simultaneously. Between-group constraints such as equal factor loadings or equal error variances can be formulated to make model estimations more similar between groups, and to investigate specific hypotheses about these similarities. Fitting a model without between-group constraints equals fitting the model to both groups separately, and combining the fit measures. The fit of a confirmatory factor analysis is represented by several indices, of which we report chi-square with degrees of freedom, the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI; recommended by Bentler 1990). For the fit to be acceptable, conventional criteria indicate that chi-square should be non-significant, CFI should be higher than .90 (preferably between .95 and 1.00), and RMSEA should be below 0.10. Wald statistics are computed in EQS to compare the current model to models in which particular estimated parameters are fixed to a specific value (mostly zero). Lagrange multiplier statistics are computed to compare a model to models in which particular restrictions are released.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

First, we investigated if there were differences between the Turkish immigrant and the Dutch group in maternal age and education. Turkish immigrant mothers (M = 26.86, SD = 2.99) were significantly younger than Dutch mothers (M = 32.71, SD = 4.19), t(138) = 9.52, p < .01, and Turkish immigrant mothers had a lower educational level on a scale of 1–5 (M = 2.83, SD = 0.72) than Dutch mothers (M = 3.40, SD = 1.08), t(138) = 3.68, p < .01.

Parenting in the Dutch and the Turkish Immigrant Groups

First, we compared Turkish immigrant and Dutch mothers on parenting behaviors (maternal sensitivity and control) without controlling for the effect of maternal age and education (see Table 1). We found significant differences between the mothers in overall maternal sensitivity and all its subscales, and in their use of authoritative control. Turkish immigrant mothers were less sensitive during the tasks: they were less supportive, gave less clear instructions, and were more intrusive than Dutch mothers. With regard to control strategies, Turkish immigrant mothers were less authoritative in their strategies during the clean-up task than Dutch mothers. No differences were found in authoritarian control. After controlling for maternal age and education, these differences between the groups remained (see Table 1).

Correlates of Parenting Behaviors in the Dutch and Turkish Immigrant Groups

To examine the associations between maternal age, education, maternal sensitivity, and authoritarian and authoritative control Pearson correlations were computed (see Table 2). Higher maternal age was related to more sensitivity and supportive presence, and less intrusiveness in the Turkish immigrant group. In the Dutch group, age was not related to any of the parenting behaviors, but was positively related to maternal education. Low maternal education was associated with more intrusiveness and less maternal sensitivity in the Dutch group. In the Turkish immigrant group, lower education was related to less maternal sensitivity and clarity of instruction. We also analyzed the associations between parenting behaviors in both ethnic groups. In the Turkish immigrant group, authoritative control was related in the expected direction to all indicators of maternal sensitivity (more authoritative control relates to more supportive presence and clarity of instruction, and less intrusiveness). In the Dutch group, more authoritative control was related to less authoritarian control and less intrusiveness of the mothers. With regard to authoritarian control, more control was associated with more maternal intrusiveness in both ethnic groups and also with less maternal sensitivity in the Turkish immigrant group. Specifically correlations between supportive presence and the other parental behaviors were higher in the Turkish immigrant group.

To investigate whether these group differences in associations between aspects of parenting were substantial, we specified a one-factor structural equation model in which the parenting behaviors were indicators of one underlying parenting dimension. On substantive grounds, we allowed measurement errors of the following variables to be correlated: (a) authoritarian and authoritative control, because these were observed using the same observation instrument; (b) authoritarian control and intrusiveness, because these both reflect a lack of respect for child autonomy; (c) intrusiveness and support, as these both indicate levels of (negative) involvement with the child, and (d) authoritative control and support, as both indicate positive involvement with the child. We also assumed error variances of the variables measured with the same instrument to be equal.

Fitting this one-factor model to both the Dutch and the Turkish immigrant group without any between group constraints resulted in an unsatisfactory fit; X ² = 16.60 (df = 8; p = 0.03), CFI = 0.945, and RMSEA = 0.125. If the fit of the unconstrained model was unsatisfactory, between group constraints only led to a decrease in model fit. Based on Lagrange multiplier statistics, we decided to improve fit by releasing the constraint of equal error variances between the sensitivity scales. Also, in accordance with the Wald statistics, we made the model more parsimonious by setting the error correlation between authoritative control and supportive presence to zero (X change² = 0.003, p = 0.96).

The resulting model is displayed in Fig. 1. Fit indices for this model were satisfactory: X² = 6.44 (df = 6, p = 0.38), CFI = 0.997, and RMSEA = 0.033. The results showed small (insignificant) loadings in both groups for authoritarian control, indicating that this variable is not needed for the factor. Also, we found relatively small loadings for authoritative control in both groups. However, authoritative and authoritarian control together did not provide a proper basis for a second factor. When (unstandardized) loadings were restricted to be equal between groups, the fit turned inadequate, indicating that the differences in loadings between the groups were indeed substantial. Thus, the observation instruments did not measure exactly the same factor in both groups, that is, the model was not measurement invariant (see Lubke et al. 2003). Most loadings, in particular for supportive presence, were higher in the Turkish immigrant group, reflecting the relatively high correlations between parenting behaviors in the Turkish immigrant group, specifically between supportive presence and the other behaviors. The error correlation between intrusiveness and supportive presence in the Turkish group was high but non-significant, due to its high standard error.

From the results in Fig. 1 we derived that authoritarian control could be removed from the model for both groups, and different patterns of error correlations were found for the Turkish immigrant and for the Dutch group. In fact, for the Dutch group, a very simple model with loadings for authoritative control, supportive presence, intrusiveness, and clarity of instruction, with all error correlations set to zero, and without any constraints did fit as well (X² = 2.437, df = 2, p = 0.30, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.056). The four loadings resulting from this alternative model were similar to those in Fig. 1.

Based on the fitted model, we computed an overall positive parenting variable by standardizing and then adding supportive presence, clarity of instruction, and authoritative control and subtracting intrusiveness, and we correlated this variable with maternal age and education in both groups. Positive parenting significantly correlated only with Turkish mothers’ age (r = .33, p < .01). We then compared the two groups and, as expected, Turkish immigrant mothers scored lower on the overall positive parenting variable F (1, 138) = 76.45, p < .01, even after controlling for maternal age and education, F (1, 138) = 30.86, p < .01.

Gender-differentiated parenting and the association between acculturation and parenting We found no gender-differentiated parenting practices in both ethnic groups, which confirmed that Dutch and Turkish immigrant mothers do not rear their sons and daughters differently.

In the Turkish immigrant group only, we also examined the associations between the Turkish and Dutch language use, emotional connectedness to the Turkish and Dutch culture, maternal age and education on the one hand, and maternal sensitivity, and authoritarian and authoritative control strategies on the other hand. Mothers’ higher emotional connectedness to the Turkish culture was related to less authoritative control (r = −.25, p < .05), and more use of the Turkish language was associated with more maternal sensitivity (r = .26, p < .05) and supportive presence (r = .28, p < .05). We found no other relations between Dutch and Turkish language use and emotional connectedness to the Dutch and the Turkish culture on the one hand, and maternal age, education, maternal sensitivity, and control on the other.

Discussion

Turkish immigrant mothers were observed to be less sensitive and to use less authoritative controlling strategies than Dutch mothers. No differences were found between the two groups in their use of authoritarian control. After controlling for maternal age and education, all differences in parenting behaviors between the groups remained significant. In both groups, parenting behaviors could be captured with similar models in which authoritarian control was not included in a one-factor model of positive parenting. This suggests that authoritarian control represents a different dimension than the other parenting behaviors, in both ethnic groups. We found no differences in gender-differentiated parenting between the two ethnic groups. With regard to maternal acculturation, Turkish immigrant mothers who felt emotionally more connected to the Dutch culture used more authoritative control, whereas mothers who spoke the Turkish language more frequently were more sensitive.

As expected, Turkish immigrant mothers were observed to be more intrusive than Dutch mothers, reflecting more demands without explanations, more (physical) interference in the child’s activities, and less respect for the child’s autonomy. In addition, Turkish immigrant mothers used less authoritative control than Dutch mothers. These results are consistent with previous studies among collectivistic oriented families in which dependence and obedience in children are encouraged, autonomy is not valued, and authoritative discipline strategies, such as verbal reasoning and induction, are less common (e.g., Ispa et al. 2004; Rubin 1998). However, contrary to our expectation, no differences in authoritarian control were found between Turkish immigrant and Dutch mothers. This may be due to the fact that the current study included only second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers. Their parenting practices may be shifting from strict authoritarian control to more inductive reasoning and explaining (Pels et al. 2006).

Consistent with our hypothesis, Turkish immigrant mothers were less supportive during the problem-solving tasks than Dutch mothers. These findings confirm previous results that compared Turkish immigrant with Dutch native families (Leseman and Van den Boom 1999). The context of a problem-solving task may have exacerbated differences in sensitivity between the two groups for two reasons. First, immigrant parents tend to have higher academic aspirations for their children than native parents of the same social class (Pels et al. 2006; Phalet and Andriessen 2003) and may thus tend to be more controlling during problem-solving interactions and therefore less responsive to the child’s wishes (Distelbrink and Pels 1996). This may have led to mothers’ putting extra pressure on their children to perform well, making them less sensitive to their children’s needs than Dutch mothers. Second, it is also possible that Turkish immigrant mothers are less used to solving structured tasks (e.g., making puzzles) with their children as this activity is less common in Turkish immigrant than in Dutch families. For example, in Turkish families puzzles were the least available toys in their homes (Nijsten 1998). However, the fact that Turkish immigrant mothers also show less authoritative control in the clean-up paradigm does suggest that the problem-solving tasks were not solely responsible for differences in supportive parenting behaviors.

When interpreting the ethnic group differences, we need to keep in mind that these differences become smaller when maternal age and education are taken into account. Thus, maternal age and education partially account for a certain amount of variance in group differences. This does not take away the fact that Turkish toddlers are more often reared by younger and lower educated mothers than Dutch toddlers and therefore as a group experience less sensitive parenting and less authoritative control. However, age and education seem more important than ethnicity in determining the parenting style of Turkish immigrant mothers. In addition, it is important to realize that there is a considerable amount of variance in sensitivity and discipline scores within the Turkish group, showing that average results can not be generalized to all individuals.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that not only in the Dutch group, but also in the Turkish immigrant group, more maternal intrusiveness was associated with lower levels of supportive presence, higher levels of authoritarian, and lower levels of authoritative control. In addition, authoritarian control was associated with lower levels of maternal sensitivity in the Turkish immigrant group. Moreover, the patterns of associations among parenting behaviors for the Dutch and the Turkish immigrant group were similar. This means that when Dutch and Turkish immigrant mothers are more supportive, they are also less intrusive, give clearer instructions, and discipline their children in a more authoritative manner. This pattern is consistent with the literature on parenting styles showing that high support, respect for autonomy and positive control go together and reflect an authoritative parenting style (Maccoby and Martin 1983). Thus, when parenting behaviors are observed, the structure of parenting behaviors in families with individualistic and families with collectivistic cultural backgrounds is similar, a finding also reported by Wu et al. (2002). We did find ethnically different patterns of error correlations for the Turkish immigrant and for the Dutch group which is probably due to the fact that the three scales of maternal support, intrusiveness, and clarity of instruction were coded by one coder in the Turkish immigrant group, and by three different coders in the Dutch group, which might have created more correlated measurement error in the Turkish immigrant group.

In both groups, authoritarian control did not load significantly on the parenting factor suggesting that authoritarian control represents a different dimension than the other parenting behaviors. As Turkish immigrant mothers were exposed to the Dutch individualistic society all their lives, these mothers are probably acquainted with parenting practices of the host society which can explain the similar patterns of associations found in both ethnic groups. However, as mentioned above, we did find that Turkish immigrant mothers were less supportive, which can not be explained by their collectivistic family values. As Turkish immigrant mothers belong to a minority group, it is possible that they experience stresses that affect their parenting (Bertrand et al. 1998; Santos et al. 1998). Indeed, the Turkish immigrant mothers from this study reported more daily stress than their Dutch counterparts (Yaman et al. 2009).

Consistent with our hypothesis, second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers did not differ in their parenting behaviors towards their sons and daughters. This was also shown in a previous study among Turkish immigrant families with school-age children in which no differences were found in supportive parenting and authoritative control with regard to the gender of the children (Wissink et al. 2006). According to previous studies, a shift from conservatism with regard to gender roles towards more egalitarian ones is taking place among Turkish immigrant women in Western Europe (Phalet and Haker 2004 as cited in Güngör and Bornstein 2008). This may suggest that gender-differentiated parenting among second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers is also shifting in which boys and girls are treated more equally.

In our study, less emotional connectedness to the Turkish culture was associated with more authoritative control. On the other hand, Turkish immigrant mothers who spoke the Turkish language more often were more supportive in their interactions with their children. These findings suggest that cultural maintenance, in the form of ethnic language use, and acculturation to the host society are both advantageous in the parenting context.

There are some limitations of our study that need to be taken into account. First, observations of parenting behaviors in the Turkish immigrant and Dutch group were conducted in different environmental contexts (home versus laboratory) which may have inflated group differences. However, several studies did not find differences in maternal sensitivity and gentle discipline between the home and laboratory settings (e.g., Bornstein et al. 2006; Van der Mark et al. 2002). Further, mean level differences need not affect the associations between the parenting behaviors. Second, we observed sensitivity and discipline during tasks that were perhaps not so common in the Turkish culture. In future studies, parenting behaviors should also be observed during daily situations, such as mealtime and bedtime. Finally, future studies may investigate the attachments to collectivistic and individualistic values of second-generation Turkish mothers and Dutch mothers and the specific influence of these values on their parenting practices. Despite these limitations, this study is one of the very few to observe parenting practices of second-generation Turkish immigrant mothers of toddlers in Europe.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that even in second-generation immigrant families the mean levels of parenting behaviors may still be different from those in the host culture, but that the patterns of associations between parenting behaviors are comparable. Our findings suggest that the focus of parenting interventions for Turkish immigrant families can be similar to that of existing programs for native parents with young children. They underscore the significance of a focus on sensitivity and authoritative control, in Turkish immigrant as well as in native Dutch families. Based on these findings, we recently started a study to test the effectiveness of an existing preventive intervention program aimed at enhancing maternal sensitivity and authoritative discipline adapted to the specific child-rearing context of Turkish immigrant families.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Alink, L. R. A., Mesman, J., Van Zeijl, J., Stolk, M. N., Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., et al. (2009). Maternal sensitivity moderates the relation between negative discipline and aggression in early childhood. Social Development, 18, 99–120.

Alink, L. R. A., Mesman, J., Van Zeijl, J., Stolk, M. N., Juffer, F., Koot, H. M., et al. (2006). The early childhood aggression curve: Development of physical aggression in 10- to 50-month-old children. Child Development, 77, 954–966.

Arends-Tóth, J., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2003). Multiculturalism and acculturation: Views of Dutch and Turkish-Dutch. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 249–266.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37, 887–907.

Belsky, J., Woodworth, S., & Crnic, K. (1996). Trouble in the second year: Three questions about family interaction. Child Development, 67, 556–578.

Bentler, P. M. (1989). EQS structural equations program manual. Los Angeles: BDMP Statistical Software.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5–68.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bertrand, R. M., Hermanns, J. M. A., & Leseman, P. P. M. (1998). Behoefte aan opvoedingsondersteuning in Nederlandse, Marokkaanse en Turkse gezinnen met kinderen van 0–6 jaar [The need for family support in Dutch, Turkish-Dutch and Moroccan-Dutch families]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Opvoeding, Vorming en Onderwijs, 14, 50–71.

Bornstein, M. H., & Cote, L. R. (2001). Mother-infant interaction and acculturation: I Behavioral comparisons in Japanese American and South American families. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 549–563.

Bornstein, M. H., Gini, M., Putnick, D. L., Haynes, O. M., Painter, K. M., & Suwalsky, J. T. D. (2006). Short-term reliability and continuity of emotional availability in mother-child dyads across contexts of observation. Infancy, 10, 1–16.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol. I. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Campbell, S. B. (1995). Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 113–149.

CBS. (2008). Allochtonen in Nederland [Migrants in The Netherlands]. Voorburg/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Çıtlak, B., Leyendecker, B., Schölmerich, A., Driessen, R., & Harwood, R. L. (2008). Socialization goals among first- and second-generation migrant Turkish and German mothers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32, 56–65.

Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (1998). Aggression and antisocial behavior. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 779–862). New York: Wiley.

Crul, M. (2008). The second generation in Europe. Canadian Diversity, 6, 17–19.

De Wolff, M. S., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and Attachment: A meta- analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development, 68, 571–591.

Deković, M., Pels, T., & Model, S. (Eds.). (2006). Child rearing in six ethnic families. The multi-cultural Dutch experience. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Distelbrink, M. J., & Pels, T. V. M. (1996). Ontwikkelingen in de etnisch-culturele positie. In J. Veenman (Ed.), Keren de kansen? De tweede-generatie allochtonen in Nederland [Turning chances? The second generation in the Netherlands] (pp. 105–132). Assen: Van Gorcum.

Egeland, B., Erickson, M. F., Moon, J. C., Hiester, M. K., & Korfmacher, J. (1990). Revised Erickson Scales: 24 month tools coding manual. Project STEEP-revised 1990. From mother-child project scales 1978. Minnesota: Department of Psychology.

Erickson, M. F., Sroufe, L. A., & Egeland, B. (1985). The relationship between quality of attachment and behavior problems in preschool in a high-risk sample. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50, 147–166.

Erol, N., & Şimsek, Z. (1997). Türkiye Ruh Sağlığı Profili: Çocuk ve gençlerde yeterlik alanları ile sorun davranışların dağılımı [Mental health profile of Turkey: distribution of competence and behavioral problems]. In N. Erol, C. Kılıç, M. Ulusoy, M. Keçeci, & Z. Şimşek (Eds.), Türkiye Ruh Sağlığı Profili: Ön Rapor [Mental Health Profile of Turkey: Preliminary Report] (pp. 12–33). Ankara: Aydoğdu Ofset.

Güngör, D., & Bornstein, M. H. (2008). Gender, development, values, adaptation, and discrimination in acculturating adolescents: The case of Turk heritage youth born and living in Belgium. Sex Roles, 60, 537–548.

Hampel, F. R., Ronchetti, E. M., & Rousseeuw, P. J. (1986). Robust statistics: The approach based on influence functions. New York: Wiley.

Harwood, R. L., Miller, J. G., & Irizarry, N. L. (1995). Culture and attachment: Perceptions of the child in context. New York: Guilford Press.

Ispa, J. M., Fine, M. A., Halgunseth, L. C., Harper, S., Robinson, J., Boyce, L., et al. (2004). Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: Variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups. Child Development, 75, 1613–1631.

Jain, A., & Belsky, J. (1997). Fathering and acculturation; Immigrant Indian families with young children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 873–883.

Kağıtçıbaşı, Ç. (2007). Family, self, and human development across cultures. Theory and applications (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Koot, H. M., Van den Oord, E. J. C. G., Verhulst, F. C., & Boomsma, D. I. (1997). Behavioral and emotional problems in young preschoolers: Cross-validity testing of the validity of the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 183–196.

Kuczynski, L., Kochanska, G., Radke-Yarrow, M., & Girnius-Brown, O. (1987). A developmental interpretation of young children’s noncompliance. Developmental Psychology, 23, 799–806.

Leseman, P. P. M., & Van den Boom, D. C. (1999). Effects of quantity and quality of home proximal processes on Dutch, Surinamese-Dutch and Turkish-Dutch pre-schoolers’ cognitive development. Infant and Child Development, 8, 19–38.

Loeber, R., & Hay, D. (1997). Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 371–410.

Lubke, G. H., Dolan, C. V., Kelderman, H., & Mellenberg, G. J. (2003). On the relationship between sources of within- and between-group differences and measurement invariance in the common factor model. Intelligence, 31, 543–566.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent- child interaction. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

Markus, H. L., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

Nijsten, C. (1998). Opvoeding in Turkse gezinnen in Nederland [Parenting in Turkish families in the Netherlands]. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Olson, S. L., Bates, J. E., Sandy, J. M., & Lanthier, R. (2000). Early developmental precursors of externalizing behavior in middle childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 119–133.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process: A social learning approach. Eugene, Oregon: Castalia.

Pels, T., Nijsten, C., Oosterwegel, A., & Vollebergh, W. (2006). Myths and realities of child rearing: Minority families and indigenous Dutch families compared. In M. Deković, T. Pels, & S. Model (Eds.), Child rearing in six ethnic families. The multi-cultural Dutch experience (pp. 213–244). Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1989). Family interaction patterns and children’s behavior problems from infancy to 4 years. Developmental Psychology, 25, 413–420.

Phalet, K., & Andriessen, I. (2003). Acculturation, motivation and educational attainment. In L. Hagendoorn, J. Veenman, & W. Vollebergh (Eds.), Integrating immigrants in the Netherlands (pp. 145–172). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Phalet, K., & Haker, F. (2004). Moslim in Nederland. Deel II: Religie, familiewaarden en binding [Muslim in the Netherlands: part II: Religion, family values, and ties] (pp. 43–61). The Hague: SCP.

Phalet, K., & Schönpflug, U. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of collectivism and achievement values in two acculturation contexts: The case of Turkish families in Germany and Turkish and Moroccan families in the Netherlands. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 186–201.

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2008). Attachment security and parenting quality predict children’s problem solving, attributions and loneliness with peers. Attachment & Human Development, 10, 319–344.

Rothbaum, F., & Weisz, J. R. (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 55–74.

Rubin, K. H. (1998). Social and emotional development from a cultural perspective. Developmental Psychology, 34, 611–615.

Rudey, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2001). Correlates of authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist cultures and implications for understanding the transmission of values. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 202–212.

Rudey, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children’s self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 68–78.

Santos, S. J., Bohon, L. M., & Sánchez-Sosa, J. J. (1998). Childhood family relationships, marital and work conflict, and mental health distress in Mexican immigrants. Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 491–508.

SCP. (2006). Turken in Nederland en Duitsland. De arbeidsmarktpositie vergeleken. [Turks in the Netherlands and Germany. Comparing the position in the labour market] Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Snyder, J., & Patterson, G. R. (1995). Individual differences in social aggression: A test of a reinforcement model of socialization in the natural environment. Behavior Therapy, 26, 371–391.

Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. A., & Collins, W. A. (2005). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to childhood. New York: Guilford Press.

Stevens, G. W. J. M., Pels, T., Vollebergh, W. A. M., & Crijnen, A. A. M. (2004). Patterns of psychological acculturation in adult and adolescent Moroccan immigrants living in the Netherlands. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 689–704.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2007). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17, 183–209.

Tremblay, R. E., Japel, C., Pérusse, D., McDuff, P., Boivin, M., Zoccolillo, M., et al. (1999). The search for the age of ‘onset’ of physical aggression: Rousseau and Bandura revisited. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 9, 8–23.

Van der Mark, I. L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2002). The role of parenting, attachment, and temperamental fearfulness in the prediction of compliance in toddler girls. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 361–378.

Van der Veen, I., & Meijnen, G. W. (2002). The parents of successful secondary school students of Turkish and Moroccan background in the Netherlands: Parenting practices and the relationship with parents. Social Behavior and Personality, 30, 303–316.

Van Oort, F. V. A., van der Ende, J., Crijnen, A. A. M., Verhulst, F. C., Mackenbach, J. P., & Bengi-Arslan, L. et al. (2006). Cultural ambivalence as a risk factor for mental health problems in ethnic minority young adults. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Ward, C. (1996). Acculturation. In D. Landis & R. Bhagat (Eds.), Handbook of intercultural training (2nd ed., pp. 124–147). Newbury Park: Sage.

Wissink, I. B., Deković, M., & Meijer, A. M. (2006). Parenting behavior, quality of the parent-adolescent relationship, and adolescent functioning in four ethnic groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 133–159.

Wu, P., Robinson, C. C., Yang, C., Hart, C. H., Olsen, S. F., Porter, C. L., et al. (2002). Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 481–491.

Yağmurlu, B., & Sanson, A. (2009). Acculturation and parenting among Turkish mothers in Australia. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40, 361–380.

Yaman, A., Mesman, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2009). Perceived family stress, parenting efficacy, and child externalizing behaviors in second-generation immigrant mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. (in press).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaman, A., Mesman, J., van IJzendoorn, M.H. et al. Parenting in an Individualistic Culture with a Collectivistic Cultural Background: The Case of Turkish Immigrant Families with Toddlers in the Netherlands. J Child Fam Stud 19, 617–628 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9346-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9346-y