Abstract

Purpose

The Child Health and Illness Profile (CHIP) has separate child (6–11 years) and adolescent (12–21 years) editions that measure youth’s self-assessed health, illness, and well-being. The purpose of this study was to revise the CHIP by combining the two editions to create the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales.

Methods

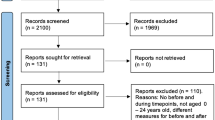

We modified the original CHIP domains of Comfort, Risk Avoidance, Satisfaction, and Resilience to reflect advances in child health conceptualization. Classical test and item response theory psychometric analyses were conducted using data collected from 2,095 children (49% boys, 80% White, 17% African-American, 3% Hispanic, Age: M = 10.6, SD = 1.0) in grades 4–6 at 34 schools.

Results

After minor revisions, 16 of the 17 scales were found to measure unidimensional self-assessed health, illness, and well-being constructs comprehensively, but with a minimal number of items. Scales were unbiased by age, gender, survey modality, and geographic location. Construct validity was demonstrated by the instrument’s capacity to differentiate among children with and without chronic illnesses and to detect expected age and gender differences.

Conclusions

The Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales may be used to reliably and accurately assess unidimensional aspects of health, illness, and well-being in clinical and population-based research studies involving youth in transition from childhood to adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health measurement and patient-reported outcome science are in the midst of major transitions, fueled by enhanced statistical methodologies and technological capabilities. At the same time, the scientific evidence for the continuity of health from childhood through mid-life and beyond has stimulated investment in understanding children’s health and how it changes over time as a function of both development and contextual influences [1]. However, the measurement of health during this phase of life has received relatively little attention. Many instruments fail to adequately capture the emerging aspects of health relevant for children as they transition into adolescence. Instruments sensitive to the changing priorities, social influences, and health-relevant behaviors of emerging adolescents are essential to understanding which children are most at risk for declines in health, which aspects of health are most susceptible to decrements, and which factors serve to maintain positive health assets through this period and in adult life.

To meet this demand and take advantage of the advances in health measurement, the child and adolescent editions of the Child Health and Illness Profile were reevaluated. The reliability and validity of the CHIP (Child and Adolescent Editions) were supported in the initial development work and further in the effective application of the CHIP in a number of studies in the United States [2–7] and abroad [8–10]. However, one significant limitation of the CHIP measurement system is uncertainty in which edition (child or adolescent) is most appropriate for use with young adolescents (aged 10–12). Further, the two editions result in some discontinuity in the measurement of health during this important transitional period. A revision of the CHIP was needed to ensure greater sensitivity to the unique health issues of children entering adolescence. This revision, reported here, is the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales. The Healthy Pathways Child-Report scales were developed to be unidimensional to support their eventual use in item banking and computerized adaptive tests and to otherwise enhance the usability of the measure by ensuring that each of the health, illness, or well-being scales could be used independently of others [11, 12]. Each scale score is intended to measure a single construct. This differs from the CHIP, which was designed to produce sub-domain scale scores, which were averaged to create domain scores. In addition to these methodological considerations, Healthy Pathways scales expanded the CHIP conceptualization of health and illness and added items to scales known from prior use of the CHIP to have limited utility or poor psychometric characteristics. Thus, the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales were designed to assess youths’ perspectives on their health, illness, and well-being during the transition from childhood to adolescence in a psychometrically sound and theoretically grounded manner.

Modifications to the CHIP conceptual framework

The CHIP conceptual framework was the starting point for the Healthy Pathways scale development. Original CHIP domains include Satisfaction (with one’s health and self), Comfort (the experience of physical and emotional symptoms and restrictions in activity due to illness), Resilience (behaviors and family involvement that protect health), Risk Avoidance (behaviors that pose risks to future health), and Achievement (developmentally appropriate role functioning in school and with peers) [13, 14]. We continued to focus on the measurement of Achievement as an important dimension of quality of life for children but now consider the Achievement domain an outcome of health rather than health itself. This is consistent with other models of health as a resources the enable achievement of desired goals [15].

Focusing on the four core domains of child health from the CHIP, we revised the measurement model in several ways and made no attempt to produce multidimensional domain scales, focusing instead on the unidimensional constructs. First, the Comfort domain, which was originally composed of physically experienced symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, and somatic complaints) and emotional distress symptoms (e.g., anger, anxiety, and depression) was expanded to include a third construct called “reactions to stress,” which are particularly distressing, involuntary responses to interpersonal and social challenges, shown to be an critical aspect of youth health [16]. Such responses as ruminating about problems and having intrusive thoughts are indicators of prolonged and maladaptive mental, behavioral, and physiological responses to stressors, an important but rarely assessed aspect of health [17–19].

Second, the Satisfaction domain was broadened to encompass global indicators of life satisfaction and happiness, while retaining the original focus on general self worth. In addition, we chose to expand the satisfaction concept by measuring self-appraisal in an area that is considered particularly salient during the child-to-adolescent transition, satisfaction with physical appearance/body image. The inclusion of a body image scale reflects pre-adolescents’ and adolescents’ preoccupation with physical appearance and the acquisition of secondary sexual characteristics. In line with this expanded conceptualization, we renamed this dimension subjective well-being to better reflect the broader concept of children’s appraisal of their lives and overall happiness.

Third, the CHIP Risk Avoidance domain assessed the tendency to take risks, behaviors that pose a threat to future health, such as smoking, drinking, and risky sexual activity, and behaviors that threaten social development, such as aggression and being a victim of bullying. Because risk behaviors that threaten future health do not occur at high rates among pre-adolescent children, who were two-thirds of our sample, we were not able to administer the individual risk behaviors scale. However, the CHIP threats to achievement scale was separated into two homogeneous sub-scales, aggression/bullying toward others and perceived peer hostility/bully victim.

Fourth, the CHIP Resilience domain, which has a strong conceptual foundation, but is very challenging to operationalize [20], seeks to assess the depth of children’s ability to cope with demands, maintain health, and engage in health enhancing activities. Healthy Pathways retained CHIP’s Active Coping and Family Involvement (here, Connectedness) scales, as well as scales that assess how connected the child feels to his peers. We added a teacher connectedness scale, because of the salience of belonging in school to the social dimension of child health, and the known empirical associations between teacher connectedness and school success [21, 22]. Teacher connectedness is a vital component of reliance among young adolescents who increasingly seek and benefit from the support of extra-familial adults [22]. These social connections provide a sense of belongingness and help “buffer” people from the negative effects of stressors [23, 24]. The Active Coping scale comprises effective strategies for solving socially demanding and self-concept threatening problems and minimizing their impact [25].

Lastly, we added a fifth domain called Energy, which in the CHIP included scales previously categorized as Resilience. Energy comprises aspects of health related to energy management and feelings of vitality and healthfulness. Scales included balanced nutrition (i.e., energy intake) and physical activity (i.e., energy expenditure), both from the original CHIP, and a new construct of vitality (i.e., feelings of being energetic), which was a modification of the CHIP’s satisfaction with health sub-domain. A child’s energy level contributes significantly to the extent of internal resources available to meet the demands of life [20]. The health, illness, and well-being constructs that are assessed by the Healthy Pathways Scales are presented in Table 1.

Methods

Participants

The Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales were administered as part of a longitudinal study of the relationships between child health and school performance (Project Healthy Pathways). The psychometric analyses presented herein were conducted using the 1st wave of data. Participants were 2,095 students in grades 4–6. Children were recruited from regular education classrooms in 34 elementary (4th–5th grade, Age: M = 10.2, SD = 0.8) or middle (6th grade, Age: M = 11.6, SD = 0.6) schools in Maryland (2 school districts) and West Virginia (1 school district). Informed parental consent was obtained for 74% of students eligible to participate; 99% of students with parental consent completed the scales. Student participants were 49% boys, 81% White, 17% African-American, 3% of another race, and 3% Hispanic. Approximately 21% of children were living in poverty as indicated by U.S. Census Bureau poverty thresholds for 2006, and 39% were living in single parent households. There were no significant differences between the demographic characteristics of participating children/families and those reported by the U.S. Census Bureau for residents in the communities in which the study was conducted.

Parent self-administered questionnaires from which we derived information on family demographics and children’s chronic disorders were returned for 71% (N = 1,517) of the student sample. There were no substantive differences in children’s self-assessed health between those whose parents returned completed questionnaires and those whose parent did not (all effect sizes <.15).

Procedures

Students in 25 out of 34 participating schools completed questionnaires on their school’s desktop computers using a web-based audio computer-assisted self-administered questionnaire. In the remaining nine schools, limitations of the school system’s network security prohibited web-based collection of data. In these schools, children completed their questionnaire using paper and pencil. Children in 4th and 5th grade completed the paper-and-pencil questionnaire as a survey administrator read the questions aloud. Sixth-grade students completed the survey by reading the items silently. All data collection was monitored by research staff and a school staff member. Study procedures were approved by the local Institutional Review Boards and those located at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Marshall University.

Measures

Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales

The majority of items included on the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales were derived from the CHIP. The development of additional items was heavily influenced by other preceding works including the KIDSCREEN [26, 27], the AddHealth Survey [28], and the Response to Stress Questionnaire [16], for which items have undergone extensive cognitive testing and validation. Items were selected from these validated measures or generated by a panel of test developers, child health experts, and clinicians (e.g., pediatricians, psychologists, and nurses). Items were pilot tested with 200 seventh-grade students in 2005. Analysis of these data including inspection of item and scale properties (e.g., frequency of missing data, range, means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha, and principal component analyses) resulted in removal of 2 physical comfort items (itchy skin and earache), 1 emotional comfort item (cry a lot), and 1 self-worth item (well coordinated). These items were removed because they failed to adequately contribute to any of the health, illness, or well-being constructs as evidenced by poor factor loadings and/or improvement in a scale’s internal consistency reliability resulting from their removal. The final health scales (n = 17), each containing 3–9 items, were produced in 2006.

Children with special health care needs screener

Parents were administered the Children with Special Health Care Needs Screener (CSHCN), a non-categorical measure of long-term health problems that increase a child’s need for medical care [29]. In addition, parents responded to the Disorders checklist from the CHIP [14] to indicate whether their child has been diagnosed with asthma or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Statistical and psychometric analyses

Advanced psychometric methods including both traditional (i.e., classical) and modern (i.e., IRT) procedures were used throughout the instrument development process [27, 30, 31]. All items had 5-point Likert scale response categories, which were reverse scored when necessary so that higher scores indicated better health (e.g., less physical discomfort, more positive self-worth). The general characteristics of each item were assessed using response frequencies, mean, standard deviation, and skewness. We evaluated the unidimensionality of scales by estimating internal consistency reliability and conducting one-factor confirmatory factor analyses using MPlus software [32]. Local independence was evaluated by examining residual correlations among items in the one-factor model.

Rasch-Masters partial credit models were fit to the data and model and item fit determined using Winsteps [11, 31]. We established item fit to the model through inspection of infit and outfit statistics and post hoc estimated empirical item discrimination parameters. Item scores were used to calibrate item “difficulty” on a logit scale with a midpoint of 0. Difficulty parameters were inspected to determine whether items supported the comprehensive measurement of the underlying latent construct with minimal gaps and redundancy.

Tests of uniform differential item functioning (DIF) were conducted to identify systematic errors due to group bias based on gender [male (n = 1,023) vs. female (n = 1,072)], grade level [4th (n = 745) vs. 5th (n = 665) vs. 6th (n = 685)], mode of survey administration [paper and pencil (n = 838) vs. computer-based (n = 1,257)], and state [Maryland (n = 1,333) vs. West Virginia (n = 762)]. Significant DIF contrast values as evidenced by the Mantel-Haenszel significance test indicate that one group of respondents is scoring higher or lower than another group of respondents on an item after adjusting for the overall scores of the respondents [33, 34].

Once scale composition was established based on results of the psychometric analyses, scale scores were calculated by averaging constituent items such that all scale scores ranged from 1 to 5 with higher scores indicating better health. Discriminative validity was evaluated by testing for expected gender- and grade-level differences in children’s health and disparities among children with and without SHCNs, asthma, and ADHD [34–39]. Between-group effect sizes (ES, d) were calculated and considered meaningful if greater than 0.2 [40].

Results

Item descriptive statistics

Details of all item descriptive characteristics, their wording, response formats, and scoring are presented in “Appendix A”. Missing data rates for all items were 2% or smaller. As is typical for child health status instruments administered in the general population [10, 27], many items were negatively skewed. However, all response categories were endorsed for every item. The largest item-level floor effect was observed for “In the past 4 weeks, how often did you eat raw vegetables?” (44% endorsed “never”), and the largest ceiling effect was observed for “When was the last time you destroyed something belonging to someone else at school?” (82% endorsed “never”).

Unidimensionality

Internal consistency was supported by Cronbach’s alpha statistics for all scales except balanced nutrition (α = .56) (Table 2). The one-factor CFA model fits the data well for 15 of the 17 scales according to two indices that provide different and complementary information about model fit, the root mean error of approximation (RMSEA) and the comparative fit indices (CFI). These fit statistics provide information about fit adjusted for model parsimony (RMSEA) and relative to a null model (CFI) [41]. Guided by suggestions provided by Hu and Bentler [42], acceptable model fit was defined by the following criteria: RMSEA ≤ 0.1 and CFI ≥ .9.

The original version of the peer connectedness scale was a poor fit for the one-factor CFA model resulting from the relatively poor factor loading (.47) of a single item, “Thinking about the past 4 weeks, have you done things with other girls and boys?” (CFI = .88, RMSEA = .12). The scale was found to be sufficiently unidimensional after this item was removed (CFI = .99, RMSEA = .06).

Consistent with its poor internal consistency reliability, the balanced nutrition scale was a poor fit for the one-factor CFA model (CFI = .57, RMSEA = .18) and despite attempts to remove items, scale unidimensionality was not achieved.

Local independence

Within each scale, item-to-item residual correlations from the one-factor CFA models were examined to test for local independence, which is the assumption that observed items are independent of each other given an individual score on the underlying latent variable (i.e., one of the Healthy Pathway scales). Two items from the emotional comfort scale were found to be locally dependent with a residual correlation of .47: “In the past 4 weeks, how often did you feel really worried?” and “Thinking about the past 4 weeks, have you felt under pressure?” The one-factor model for emotional comfort was significantly improved through the removal of the “pressure” item (CFI changed from .90 to .94; RMSEA from .10 to .07). Residual correlations were <.20 for all other item pairs within scales indicating that all remaining items met the local independence assumption.

Estimated Rasch parameters and model fit

Scales were revised based on results of the preceding analyses. Thereafter, all scales except for balanced nutrition, which failed to meet the assumption of unidimensionality, were fit to the Rasch-Masters partial credit model. All but two items had satisfactory fit statistics. The degree to which children reported “talking to a friend” as a means of coping with a social or school-related problem failed to adequately discriminate among children with varying levels of active coping capacities (INFIT = 1.23; OUTFIT = 1.31; a = 0.62). The frequency with which children “kept remembering what happened” in response to a stressful event was unpredictable among children at both high and low levels of negative stress reactions (INFIT = 1.19; OUTFIT = 1.24; a = 0.69). As a result, these items were removed from their respective scales.

Item fit statistics and parameters for the final scales are presented in Table 3. Each scale covered a broad range of estimated ability level (theta) in its underlying latent construct. Average coverage was 8.6 logits. The scale with the largest range in theta was life satisfaction (ranged from −4.7 to 6.0 logits), and the scale with the smallest range was aggression/bullying (ranged from −2.8 to 2.6 logits). Scale-level ceiling effects greater than 10% of the sample were observed for the aggression/bullying (51%), peer hostility/bully victim (29%), self-worth (18%), life satisfaction (16%), and body image (12%). Minimal floor effects (<1% of the sample) were observed for all scales. On average, item difficulties (deltas) covered 1.1 logits with the largest coverage observed for physical comfort (ranged from −.9 to 1.3 logits) and the smallest for self-worth (ranged from −.1 to .1 logits). As shown in Table 3, there was minimal redundancy in items.

Differential item functioning

The item difficulty contrast by gender was statistically significant for a single item on the Vitality scale, “How often do you feel really strong?” (contrast = −.45, P < .0001) (Fig. 1). When boys and girls had comparable levels of vitality, boys were more likely than girls to indicate that they had a high degree of body strength. In contrast, modest although sub-threshold DIF was observed for two other items on the Vitality scale, “How often do you feel really healthy?” (contrast = .23) and “How is your health?” (contrast = .31). Because both of these items were slightly easier for girls than for boys, the detected DIF of Vitality items essentially did not change the total test score level due to cancellation across items with DIF in opposing directions [34]. Figure 2 displays the test characteristic curve (the expected scale score as a function of Θ) for the Vitality scale. The expected scale score did not substantially differ between boys and girls across the full range of the construct.

No significant differential item functioning was observed by grade level, mode of survey administration, or geographic location.

Construct validity

Table 4 shows differences in the Healthy Pathway scale scores among children by gender, school type (elementary vs. middle), and presence of a special healthcare need, asthma, and ADHD. Scale score means and standard deviations for the subgroups are presented in “Appendix B”. These results are consistent with previously reported group differences [34–40].

Discussion

This study described the development and psychometric validation of the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales. Based primarily on the CHIP, the scales merged the child and adolescent editions of the CHIP with the intent of improving the measurement of self-assessed health, illness, and well-being among children transitioning into adolescence. We employed modern measurement techniques in the development and validation of the scales because these methods provide essential information about the degree to which items cover a full range of underlying latent constructs without redundancy, support the identification of items that are biased against subgroups in the population, and provide the foundation for the development of item banking and computerized adaptive tests. With the exception of the KIDSCREEN [27], the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales are the only broad self-reported child health instrument that has been developed using modern measurement techniques.

Our findings demonstrate that 16 of the 17 Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales are reliable, simultaneously comprehensive and efficient, and free of gender, age, modality, and geographic location bias. The scales are meaningful in that they are effective at differentiating children based on gender, age, and presence of a long-term medical condition. Consistent with prior research, boys were more likely than girls to experience emotional comfort [38] and positive body image [36, 37] and to engage in physical activity [39] and aggressive behavior [43, 44]. Conversely, girls were more likely to employ active coping strategies such as seeking support from family or friends to deal with a stressful situation [45]. Girls also reported higher levels of school engagement than boys.

Children with a special healthcare need (SHCN) reported modestly poorer physical comfort, vitality, life satisfaction, and peer interactions as evidenced by both reports of connectedness with peers and the frequency with which they are bullied, findings that are similar to other studies [27, 46]. Similar findings were evidenced for children with ADHD and as expected, these children experienced many health challenges [35, 47]. As expected, children with asthma experienced poorer physical comfort but did not differ from children without asthma on other indicates of health, illness, and well-being [48–50].

The development of item banks for children and youth is in its nascent stages of development [51, 52]. With this ultimate goal in mind, we believe that the Healthy Pathway scales will be expanded and modified over the next several years. We are publishing all the items, their characteristics, and the scale psychometrics to engage other investigators in this process. Our findings suggest several potential areas for future development. For example, the balanced nutrition items were only minimally inter-correlated, suggesting that this scale may represent more than one latent construct (e.g., positive and negative nutrition behaviors). The nutrition items in the original CHIP were treated as an index, because they did not behave as a scale empirically [14]. Multiple dimensions of dietary behavior may emerge with the addition of other items including those pertaining to the ingestion of fast food or whole grains, or eating habits such as partaking in family meals [53].

The 3-item peer hostility scale may be strengthened with the addition of items that assess indirect or relational bullying such as spreading rumors or purposefully excluding someone. These experiences are associated with social and emotional problems, particularly among girls [44, 54, 55]. Expanding the peer hostility scale to include more commonly experienced types of bullying is also needed to reduce the scale’s ceiling effect. Similarly, the aggression/bullying scale should be supplemented with items indicative of less severe problems. Ceiling effects should also be addressed for the self-worth, life satisfaction, and body image subscales by adding items indicative of extreme well-being, which are more likely to be endorsed with moderate responses (e.g., sometimes). Finally, although the majority of items were derived from validated instruments for which the items have undergone extensive cognitive testing (e.g., CHIP, KIDSCREEN), some items, particularly those that assess teacher connectedness and school engagement, could be improved through formal cognitive debriefing.

The Healthy Pathways measurement model will almost certainly be extended in the future to comprehensively assess the increasingly complex internal and social experiences of adolescents. Additional components of an adolescent health framework may include satisfaction with work/occupation (which was included in the adolescent edition of the CHIP), sexual self-concept, and connectedness with non-parent or non-teacher adults (e.g., coach or mentor). An advantage of our approach to developing independent unidimensional scales is that additional scales may be added to the measurement system without reevaluating the original scales.

Finally, although scales were found to be free of bias based on gender, age, administration modality, and geographic location, future efforts should include attempts to validate the scales among race/ethnic minorities and urban residents. Item functioning should also be evaluated among children of a broader age range.

The Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales represent a significant advance in the conceptualization and measurement of child health, illness, and well-being. Because the scales were developed using IRT methods, it is possible to obtain estimates of constructs that are independent of the particular set of items administered [11]. Thus, future development of the scales will include the addition of items to maximize coverage of the underlying health constructs, resulting in the creation of expanded item banks and computerized adaptive test versions of the instruments, which are increasingly recognized as the preferred strategies for assessing outcomes in clinical effectiveness research [31, 51, 52].

Abbreviations

- CHIP:

-

Child health and illness profile

- CHIP-CE:

-

Child health and illness profile-child edition

- CHIP-AE:

-

Child health and illness profile-adolescent edition

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- SHCN:

-

Special health care need

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

References

National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine. (2004). Children’s health, the nation’s wealth: Assessing and improving child health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Altshuler, S. J., & Poertner, J. (2002). The child health and illness profile—adolescent edition: Assessing well-being in group homes or institutions. Child Welfare, LXXXI(3), 495–513.

Forrest, C. B., Tambor, E., Riley, A. W., Ensminger, M. E., & Starfield, B. (2000). The health profile of incarcerated male youths. Pediatrics, 105(1), 286–291.

Hack, M., Cartar, L., Schluchter, M., Klein, N., & Forrest, C. B. (2007). Self-perceived health, functioning and well-being of very low birth weight infants at age 20 years. Journal of Pediatrics, 151(6), 635–641.

Starfield, B., Riley, A. W., Witt, W. P., & Robertson, J. (2002). Social class gradients in health during adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(5), 354–361.

Starfield, B., & Riley, A. W. (1998). Profiling health and illness in children and adolescents. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Starfield, B., Robertson, J., & Riley, A. W. (2002). Social class gradients and health in childhood. Journal of Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2(4), 238–246.

Berra, S., Borrell, C., Rajmil, L., Estrada, M. D., Rodriguez, M., & Riley, A. W. (2006). Perceived health status and use of healthcare services among children and adolescents. European Journal of Public Health, 16(4), 405–414.

Rajmil, L., Serra-Sutton, V., Alonso, J., Herdman, M., Riley, A., & Starfield, B. (2003). Validity of the Spanish version of the child health and illness profile-adolescent edition (CHIP-AE). Medical Care, 41(10), 1153–1163.

Riley, A. W., Chan, S. K., Prasad, S., & Poole, L. (2007). A global measure of child health-related quality of life: Reliability and validity of the child health and illness profile—child edition (CHIP-CE) global score. Journal of Medical Economics, 10(1), 91–106.

Hambleton, R. K., Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. J. (1991). Fundamentals of item response theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hays, R. D., Morales, L. S., & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Medical Care, 38(9 suppl), II-28–II-48.

Riley, A. W., Forrest, C. B., Rebok, G. W., Starfield, B., Green, B. F., Robertson, J. A., et al. (2004). The child report form of the CHIP-child edition: Reliability and validity. Medical Care, 42(3), 221–231.

Starfield, B., Riley, A., Breen, B., Ensminger, M., Ryan, S., & Kelleher, K. (1995). The adolescent child health and illness profile: A population-based measure of health. Medical Care, 33(5), 553–566.

Seedhouse, D. (1986). Health: The foundation of achievement. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 976–992.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127.

Kliewer, W., Reid-Quinones, K., Shields, B. J., & Foutz, L. (2009). Multiple risks, emotional regulation skills, and cortisol among low-income African American youth: A prospective study. Journal of Black Psychology, 35(1), 24–43.

Sontag, L. M., Graber, J. A., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Warren, M. P. (2008). Coping with social stress: Implications for psychopathology in young adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(8), 1159–1174.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder and adaptation (pp. 739–795). New York: Wiley.

Birch, S., & Ladd, G. (1998). Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 934–946.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfield, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, E. Taylor, & J. E. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health: Social psychological aspects of health (pp. 253–277). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78(3), 458–467.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gosch, A., Abel, T., Auquier, P., Bellach, B. M., Bruil, J., et al. (2001). Quality of life in children and adolescents—a European public health perspective. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin, 46, 297–302.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Erhart, M., Bruil, J., Power, M., et al. (2008). The KIDSCREEN-52 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Value in Health, 11(4), 645–658.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 823–832.

Bethell, C. D., Read, D., Stein, R. K., Blumberg, S. J., Wells, N., & Newacheck, P. W. (2002). Identifying children with special health care needs: Development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2(1), 38–48.

Edelen, M. O., & Reeve, B. B. (2007). Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Quality of Life Research, 16(1), 5–18.

Reeve, B. B., Hays, R. D., Bjorner, J. B., Cook, K. F., Crane, P. K., Teresi, J. A., et al. (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Medical Care, 45(Suppl 1), S22–S31.

Muthen, L. K., Muthen, B. O. (1998–2004). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Linacre, J. (2004). A user’s guide to Winsteps Rasch-model computer program.

Langer, M. M., Hill, C. D., Thissen, D., Burwinkle, T. M., Varni, J. W., & DeWalt, D. A. (2008). Item response theory detected differential item functioning between healthy and ill children in quality-of-life measures. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(3), 268–276.

Riley, A. W., Spiel, G., Coghill, D., Dopfner, M., Falissard, B., Lorenzo, M. J., et al. (2006). Factors related to health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among children with ADHD in Europe at entry into treatment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 5(1), 38–45.

Feingold, A., & Mazzella, R. (1998). Gender differences in body image are increasing. Psychological Science, 9(3), 190–196.

Jones, D. C. (2001). Social comparison and body image: Attractiveness comparisons to models and peer among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles, 45(9/10), 645–655.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Lewinsohn, M., Gotlib, I. H., Seeley, J. R., & Allen, N. B. (1998). Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 109–117.

Trost, S. G., Pate, R. R., Sallis, J. F., Freedson, P. S., Taylor, W. C., Dowda, M., et al. (2002). Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(2), 47–58.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Bjorkqvist, K., Legerspetz, K. M. J., & Kaukiainen, A. (1992). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 18(1), 117–127.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722.

Berndt, T. J. (1982). The features and effects of friendship in early adolescence. Child Development, 53(6), 1447–1460.

Power, T. J. (2006). Collaborative practices for managing children’s chronic health conditions. In L. Phelps (Ed.), Chronic health-related disorders in children: Collaborative medical and psychoeducational interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Birkhart, P. V., Svavarsdottir, E. K., Rayens, M. K., Oakley, M. G., & Orlygsdottir, B. (2009). Adolescents with asthma: Predictors of quality of life. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(4), 860–866.

French, D., Carroll, A., & Christie, M. (1998). Health-related quality of life in Australian children with asthma: Lessons for the cross-cultural use of quality of life instruments. Quality of Life Research, 7(5), 409–419.

Forrest, C. B., Starfield, B., Riley, A. W., & Kang, M. (1997). The impact of asthma on the health status of adolescents. Pediatrics, 99, E1.

Cella, D., Gershon, R., Lai, J., & Choi, S. (2007). The future of outcomes measurement: Item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Quality of Life Research, 16(1), 133–141.

Cella, D., Yount, S., Rothrock, N., Gershon, R., Cook, K., Reeve, B., et al. (2007). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care, 45(Suppl 1), S3–S11.

Gibson, R. S. (2005). Principles of nutritional assessment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Galen, B. R., & Underwood, M. K. (1997). A developmental investigation of social aggression among children. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 589–600.

Stanley, L., & Arora, T. (1998). Social exclusion amongst adolescent girls: Their self-esteem and coping strategies. Education Psychology in Practice, 14(2), 94–100.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). YRBSS 2009 questionnaires and item rationale. http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/questionnaire_rationale.htm. Accessed 3 Sept 2009.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gosch, A., Rajmil, L., Erhart, M., Bruil, J., Duer, W. (2005). KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Review of Pharmoeconomics and Outcomes Ressearch, 5(3), 353–364.

Eccles, J. S., Early, D., Frasier, K., Belansky, E., McCarthy, K. (1997). The relation of connection, regulation, and support for autonomoy to adolescents’ functioning. Journal of Adolescence Research, 12(2), 263–286.

Simons-Morton, B. G., Crump, A. D. (2002). The association of parental involvement and social competence with school adjustment and engagement among sixth graders. Journal of School Health, 73(3), 121–126.

Blumenfeld, P., Modell, J., Bartko, W. T., Secada, W., Fredricks, J., Friedel, J., et al. (2005). School engagement of inner city students during middle childhood. In C. R. Cooper, C. G. Coll, W. T. Bartko, H. M. Davis, & C. Chatman C. (Eds), Developmental Pathways through Middle Childhood: Rethinking Diversity and Contexts as Resources for Children's Developmental Pathways (pp. 145–170). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01HD048850 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table 5.

Appendix B

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bevans, K.B., Riley, A.W. & Forrest, C.B. Development of the Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales. Qual Life Res 19, 1195–1214 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9687-4