The death certificate is an important medical document that impacts mortality statistics and health care policy. Resident physician accuracy in completing death certificates is poor. We assessed the impact of two educational interventions on the quality of death certificate completion by resident physicians. Two-hundred and nineteen internal medicine residents were asked to complete a cause of death statement using a sample case of in-hospital death. Participants were randomized into one of two educational interventions: either an interactive workshop (group I) or provided with printed instruction material (group II). A total of 200 residents completed the study, with 100 in each group. At baseline, competency in death certificate completion was poor. Only 19% of residents achieved an optimal test score. Sixty percent erroneously identified a cardiac cause of death. The death certificate score improved significantly in both group I (14±6 vs 24±5, p<0.001) and group II (14±5 vs 19±5, p<0.001) postintervention from baseline. Group I had a higher degree of improvement than group II (24±5 vs 19±5, p<0.001). Resident physicians’ skills in death certificate completion can be improved with an educational intervention. An interactive workshop is a more effective intervention than a printed handout.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jordan JM, Bass MJ. Errors in death certificate completion in a teaching hospital. Clin Invest Med. 1993;16:249–55.

Weeramanthri T, Bensford B. Death certification in Western Australia—classification of major errors in certificate completion. Aust J Public Health. 1992;16:431–4.

Slater DN. Certifying the case of death: an audit of wording inaccuracies. J Clinic Pathol. 1993;46:232–4.

Peach HG, Brumley DJ. Death certification by doctors in non-metropolitan Victoria. Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27:178–82.

Gjersoe P, Andersen SE, Molbak AG, et al. Reliability of death certificates. The reproducibility of the recorded causes of death in patients admitted to departments of internal medicine. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:5030–4.

Maudsley G, Williams E. Death certification by house officers and general practitioners—practice and performance. J Public Health Med. 1993;15:192–201.

Pain CH, Aylin P, Taud NA, et al. Death certification production and evaluation of training video. Med Educ. 1996;30:434–9.

Horner JS, Horner JW. Do doctors read forms? A one-year audit of medical certificates submitted to a crematorium. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:371–6.

Barber JB. Improving the accuracy of death certificates. J Natl Med Assoc. 1992;84(12):1007–8.

Hanzlick R, ed. The Medical Cause of Death Manual. Instructions for Writing Cause of Death Statements for Deaths Due to Natural Causes. Northfield (IL): College of American Pathologists; 1994:p. 8, 104.

Magrane BP, Gilliland MG, King DE. Certification of death by family physicians. Am Fam Phys. 1997;56:1433–8.

Fifty years of death certificates: The Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1066–7. Editorial; comment.

Sorlie PD, Gold EB. The effect of physician terminology preference on coronary heart disease mortality: an artifact uncovered by the 9th revision ICD. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:148–52.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Martin DO, Larson MG, Levy D. Accuracy of death certificates for coding coronary heart disease as the cause of death. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1020–6.

Myers KA, Farquhar DR. Improving the accuracy of death certification. CMAJ. 1998;158:1317–23.

Dallal GE. First generator. Available at http://www.randomization.com. Accessed on 10/08/2000. (http://www.randomization.com).

Lakkireddy DR, Gowda MS, Basarakodu KR, Murray CW, Vacek JL. Death certificate completion—how well are physicians trained and are cardiovascular causes overstated? Am J Med. 2004;117:492–8.

Behrendt N, Heegaard S, Fornitz GG. The hospital autopsy: an important factor in hospital quality assurance. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999;161:5543–7.

Lu TH, Lee MC, Chou MC. Accuracy of cause of death coding in Taiwan: types of miscoding and effects on mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:336–43.

Cina SJ, Selby DM, Clark B. Accuracy of death certification in two tertiary care military hospitals. Mil Med. 1999;164:897–9.

Smith Sehdev AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause of death statement. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:277–84.

Roberts IS, Gorodkin LM, Benbow EW. What is a natural cause of death? A survey of coroners in England and walks approach borderline cases. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:367–73.

Hanzlick R. Death certificates. The need for further guidance. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1993;14:249–52.

Johansson LA, Westerling R. Comparing Swedish hospital discharge records with death certificates: implications for mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:495–502.

Sidenius KE, Munch EP, Madsen F, Lange P, Viskum K, Søes-Petersen U. Accuracy of recorded asthma deaths in Denmark in a 12 months period in 1994/95. Respir Med. 2000;94:373–7.

Weeramanthri T, Beresford W, Sathianathan V. An evaluation of an educational intervention to improve death certification practice. Aust Clin Rev. 1993;13:185–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript would like to acknowledge Ms. Kay Ryschon, MS, of Valentine, NE, USA, for her statistical support during the development of this study. We also thank Dr. Andrea Natale, Head, Division of Electrophysiology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and Dr. Syed Mohiuddin, Director, Creighton Cardiac Center, Omaha, NE, USA, for his critical review of the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Kamani Lankachandra, MD, Director of Anatomic Pathology, UMKC School of Medicine, for her valuable feedback on various issues related to death certificates. We appreciate the secretarial support of Ms. Caroline Murray, Mid America Cardiology, in the preparation of this manuscript. The powerpoint presentation of the tutorial can be obtained from the corresponding authors if the reader wishes to use it.

Dr. Manohar Gowda passed away during the later half of this study. The other authors would like to dedicate this paper to his memory, great spirit, and kind heart.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Test Case 1

The patient was a 29-year-old Caucasian male with known multiple sclerosis for 3 years complicated by paraplegia and chronic decubitus ulcers. His other medical conditions include atopic dermatitis and asthma. He was admitted to the intensive care unit with high-grade fevers, chills, and rigors, and leukocytosis (19×103/μL) with bandemia of 58%. Vital signs included the following: temperature, 102.5°F; pulse, 128 bpm; blood pressure, 85/55 mmHg; and oxygen saturation, 96% on room air. He also had a chronic indwelling urinary catheter, which had been changed. Urine analysis revealed gross pyuria and bacteriuria. Urine and blood cultures were obtained. He was started on levofloxacin (500 mg once daily intravenously) and was given 1.5 L of fluid bolus, after which his blood pressure improved to 115/60 mmHg. He was continued on normal saline at 100 cm3/h. He was stable for the next 12 hours when his blood pressure dropped to 60/40 mmHg. At that time, he was started on neosynephrine to titrate to systolic blood pressure >80 mmHg. During the next 36 hours, systolic blood pressure stabilized at 80 to 90 mmHg, and serum potassium levels increased from 3.6 to 7.3 mEq/L, whereas serum creatinine levels rose from 1.4 to 4.6 mg/dL. Oxygen saturation dropped to 79% on room air, and he was subsequently put on a 100% nonrebreather mask. Blood pressure started to decrease, and telemetry showed sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. A Code Blue was called. No pulse or spontaneous breaths were detected. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, and he was intubated. No pulse or change in rhythm was noted after three DC shocks and three boluses of intravenous epinephrine. Finally, he converted to normal sinus rhythm with shock after lidocaine bolus. He was started on a lidocaine drip. Shock profile was sent, and kayexalate per a nasogastric tube was given to address the high serum potassium level. He remained in normal sinus rhythm with multiple frequent premature ventricular contractions and a blood pressure of 60/30 mmHg. Neosynephrine was increased, and dopamine was started. Another Code Blue was called when the patient was found to be in asystole. Epinephrine and atropine (three boluses each) were administered, and the monitor showed coarse ventricular fibrillation after the fourth dose of atropine. No pulse was noted. He was shocked three times at 360 J, and a lidocaine bolus was given followed by another shock and a procainamide bolus. He was also given a bolus of bretylium as a last resort followed by another shock. Fifty minutes after initiating the second Code Blue, upon agreement with everyone involved, resuscitation attempts were discontinued, and the patient was declared dead.

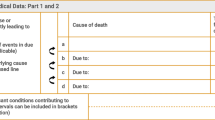

Correct completion of test case 1 would be as follows: Part I, line A = septic shock, line B = urinary tract infection, line C = neurogenic bladder, line D = multiple sclerosis; Part II = atopic dermatitis and asthma.

Test Case 2

The patient was a 39-year-old African American woman with known sickle cell disease for the past 22 years. She has been on chronic pain medications for intermittent episodes of sickle cell crises. She was well known to the internal medicine service from her multiple admissions over the last several years for sickle cell crises and her dependence on chronic pain medications. Her other medical problems include hypertension, mild renal insufficiency, and moderate mitral stenosis. She was admitted to the internal medicine service with complaints of painful sickle cell crises involving the lower extremities, fever, nausea, and vomiting. She had mild leukocytosis (12×103/μL). Vital signs included the following: temperature, 101°F; pulse, 114 bpm; blood pressure, 180/95 mmHg; and oxygen saturation, 92% on room air. Her hematocrit was 28, and Cr/BUN was 1.3/38. She was being treated with IV fluids, 3 L of inhaled O2, and pain medications. Also, she was restarted on her home diltiazem and ACE-I with improvement in her BP. The next day, she started complaining of more leg pain with some tenderness in her right calf. On examination, the right calf looked bigger than the left, and the intern had promptly started the patient on IV heparin, and the patient was wheeled down to the radiology department for bilateral lower extremity Doppler to assess for deep venous thrombosis. As the test was completed, patient complained of sudden onset of pleuritic chest pain with shortness of breath. Her oxygen saturation dropped to 82% on 2 L, and she was subsequently put on a 100% nonrebreather mask. She became hypotensive, and a Code Blue was called. Patient subsequently had agonal breathing without a palpable pulse. Portable monitoring unit showed sinus tachycardia at 140 bpm. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, and she was intubated. No pulse or change in rhythm was noted after three boluses of intravenous epinephrine and continued CPR. Monitoring showed ventricular fibrillation, and a 360-J DC shock transiently brought the patient back to sinus tachycardia with feeble pulse. As the intern on the code team started getting central venous access through the right femoral vein, the patient went into asystole, and CPR was reinitiated. After 30 more minutes of ACLS upon agreement with everyone involved, resuscitation attempts were discontinued, and the patient was declared dead.

Correct completion of the test case 2 would be as follows: Part I, line A = massive pulmonary embolism, line B = lower extremity deep venous thrombosis, line C = sickle cell disease, Part II = hypertension, mild renal insufficiency and mitral stenosis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lakkireddy, D.R., Basarakodu, K.R., Vacek, J.L. et al. Improving Death Certificate Completion: A Trial of Two Training Interventions. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 544–548 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0071-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0071-6