Background

A clearly stated clinical decision can induce a cognitive closure in patients and is an important investment in the end of patient–physician communications. Little is known about how often explicit decisions are made in primary care visits.

Objective

To use an innovative videotape analysis approach to assess physicians’ propensity to state decisions explicitly, and to examine the factors influencing decision patterns.

Design

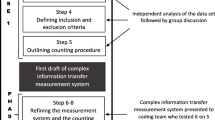

We coded topics discussed in 395 videotapes of primary care visits, noting the number of instances and the length of discussions on each topic, and how discussions ended. A regression analysis tested the relationship between explicit decisions and visit factors such as the nature of topics under discussion, instances of discussion, the amount of time the patient spoke, and competing demands from other topics.

Results

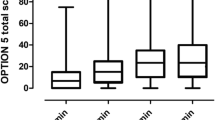

About 77% of topics ended with explicit decisions. Patients spoke for an average of 58 seconds total per topic. Patients spoke more during topics that ended with an explicit decision, (67 seconds), compared with 36 seconds otherwise. The number of instances of a topic was associated with higher odds of having an explicit decision (OR = 1.73, p < 0.01). Increases in the number of topics discussed in visits (OR = 0.95, p < .05), and topics on lifestyle and habits (OR = 0.60, p < .01) were associated with lower odds of explicit decisions.

Conclusions

Although discussions often ended with explicit decisions, there were variations related to the content and dynamics of interactions. We recommend strengthening patients’ voice and developing clinical tools, e.g., an “exit prescription,” to improving decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Braddock CH, 3rd, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(24):2313–20.

Frankel R, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. J Med Pract Manage. 2001;16(4):184–91.

Consensus Development Conference NIH. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Paper presented at: NIH Consensus Development Conference; 1991.

Charon R, Greene MG, Adelman RD. Multi-dimensional interaction analysis: a collaborative approach to the study of medical discourse. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):955–65

Cook M. Final Report: Assessment of Doctor–Elderly Patient Encounters, Grant No. R44 AG5737-S2. Washington, D.C: National Institute of Aging; 2002.

American Medical Association. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. 2001/2002 Edition ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2001.

US Census Bureau. 2001.

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans 2000: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000.

Tai-Seale M, Bramson R, Drukker D, et al. Understanding primary care physicians’ propensity to assess elderly patients for depression using interaction and survey data. Med Care. 2005;43(12):1217-24.

Feinstien A, Cicchetti D. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):543–9.

Cicchetti D, Feinstein A. High agreement but low kappa: II. Resolving the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):551–8.

Bakeman R, Quera V, McArther D, Robinson BF. Detecting sequential patterns and determining their reliability with fallible observers. Psychol Methods. 1997;2(4):357–70.

Ickes W, Marangoni C, Garcia S. Studying empathic accuracy in a clinically relevant context. In: Ickes W, ed. Empathic Accuracy. New York: Guilford Press; 1997:282–310.

Eide HQV, Graugaard P, Finset A. Physician–patient dialogue surrounding patients’ expression of concern: applying sequence analysis to RIAS. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(1):145–55.

Ware JE Jr., Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the medical outcomes study. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):AS264–79.

Balsa AI, McGuire TG, Meredith LS. Testing for statistical discrimination in health care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):227–52.

Bertakis KD, Callahan EJ, Helms LJ, Azari R, Robbins JA. The effect of patient health status on physician practice style. Fam Med. 1993;25(8):530–5.

Sleath B, Rubin RH. Gender, ethnicity, and physician–patient communication about depression and anxiety in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):243–52.

Jacobs LR, Morone JA. Health and Wealth: the American Prospect Online; 2004.

Phelps CE. The methodologic foundations of studies of the appropriateness of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(17):1241–5.

Henderson JT, Hudson Scholle S, Weisman CS, Anderson RT. The role of physician gender in the evaluation of the National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health: test of an alternate hypothesis. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14(4):130–9.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288(6):756–64.

Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260–73.

Weiss L, Blustein J. Faithful patients: the effect of long-term physician–patient relationships on the costs and use of health care by older Americans. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):135–6.

Merrill J, Laux L, Thornby J. Troublesome aspects of the patient–physician relationship: a study of human factors. South Med J. 1987;80(10):1211–5.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000.

Kraemer HC, Blasey CM. Centering in regression analyses: a strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(3):141–51.

STATACorp. STATA Reference Manual. College Station, TX; 2003.

Tannen D. The power of talk: who gets heard and why. Harvard Bus Rev. 1995;73(5):138–48.

Feldman SR, John G, Chen JYH, Fleischer AB. Effects of systematic asymmetric discounting on physician–patient interactions: a theoretical framework to explain poor compliance with lifestyle counseling. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2002;2:8.

Becker G, Grossman M, Murphy K. Rational addiction and the effect of price on consumption. Am Econ Rev. 1991;81(2):237–41 (May).

Roter D, Hall J. Studies of doctor–patient interactions. Annu Rev Public Health. 1989;10:163–80.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michele Greene for providing the coding guide for the Multidimensional Interaction Analysis (MDIA) system and Thomas McGuire, Charles Huber, Emil Berkanovic, Suojin Wang, three anonymous reviewers, and the Deputy Editor Richard Frankel for helpful comments. Funding from NIMH MH0193, NIA AG 15737, and the Texas A&M Health Science Center School of Rural Public Health and the Scott & White Health Plan Health Services Research Program is gratefully acknowledged.

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tai-Seale, M., Bramson, R. & Bao, X. Decision or No Decision: How Do Patient–Physician Interactions End and What Matters?. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 297–302 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0086-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0086-z