Abstract

Background

Although current guidelines emphasize the importance of cholesterol knowledge, little is known about accuracy of this knowledge, factors affecting accuracy, and the relationship of self-reported cholesterol with cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Methods

The 39,876 female health professionals with no prior CVD in the Women’s Health Study were asked to provide self-reported and measured levels of total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Demographic and cardiovascular risk factors were considered as determinants of awareness and accuracy. Accuracy was evaluated by the difference between reported and measured cholesterol. In addition, we examined the relationship of self-reported cholesterol with incident CVD over 10 years.

Results

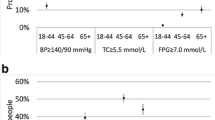

Compared with women who were unaware of their cholesterol levels, aware women (84%) had higher levels of income, education, and exercise and were more likely to be married, normal in weight, treated for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, nonsmokers, moderate drinkers, and users of hormone therapy. Women underestimated their total cholesterol by 9.7 mg/dL (95% CI: 9.2–10.2); covariates explained little of this difference (R 2 < .01). Higher levels of self-reported cholesterol were strongly associated with increased risk of CVD, which occurred in 741 women (hazard ratio 1.23/40 mg/dL cholesterol, 95% CI: 1.15–1.33). Women with elevated cholesterol who were unaware of their level had particularly increased risk (HR=1.88, P <. 001) relative to aware women with normal measured cholesterol.

Conclusion

Women with obesity, smoking, untreated hypertension, or sedentary lifestyle have decreased awareness of their cholesterol levels. Self-reported cholesterol underestimates measured values, but is strongly related to CVD. Lack of awareness of elevated cholesterol is associated with increased risk of CVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97.

National Cholesterol Education Program. Second Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II). Circulation. 1994;89:1333–445.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2nd ed. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress in chronic disease prevention factors related to cholesterol screening and cholesterol level awareness—United States, 1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1990;39:633–7.

Schucker B, Wittes J, Santanello N, et al. Change in cholesterol awareness and action: results from national physician and public surveys. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:666–73.

Pieper RM, Arnett DK, McGovern PG, Shahar E, Blackburn H, Luepker RV. Trend in cholesterol knowledge and screening and hypercholesterolemia awareness and treatment, 1980–1992: the Minnesota Heart Survey. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2326–32.

Nash IS, Mosca L, Blumenthal RS, Davidson MH, Smith SC, Pasternak RC. Contemporary awareness and understanding of cholesterol as a risk factor. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1597–1600.

Nieto FJ, Alonso J, Chambless L, et al. Population awareness and control of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:677–84.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State-specific cholesterol screening trends—United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:750–5.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cholesterol screening and awareness—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(36).

Mosca L, Ferris A, Fabunmi R, Robertson RM. Tracking women’s awareness of heart disease—an American Heart Association National Study. Circulation 2004;109:573–9

Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, Jenkins PL, Lewis C, Pearson TA. Validity of cardiovascular disease risk factors assess by telephone survey: the Behavioral Risk Factor Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:561–71.

Bowlin S, Morrill B, Nafziger A, Lewis C, Pearson T. Reliability and changes in validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease risk factors using dual response: The Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:511–7.

Natarajan S, Lipsitz SR, Nietert PJ. Self-report of high cholesterol-determinants of validity in U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:13–21.

Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123:894–900.

Newell S, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher R, Ireland M. Accuracy of patients’ recall of Pap and cholesterol screening. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1431–5.

Murdoch M, Wilt TJ. Cholesterol awareness after case-finding: do patients really know their cholesterol numbers? Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:284–9.

Bairey Merz CN, Felando MN, Klein J. Cholesterol awareness and treatment in patients with coronary artery disease participating in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1996;16:117–22.

Rexrode KM, Lee I, Cook NR, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:19–27.

Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293–304.

Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. The Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:47–55.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2000.

Harawa NT, Morgenstern H, Beck J, Moore A. Correlates of knowledge of one’s blood pressure and cholesterol levels among older members of a managed care plan. Aging. 2001;13:95–104.

Nelson K, Norris K, Mangione CM. Disparities in the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of high serum cholesterol by race and ethnicity—data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:929–35

Brennan RM, Crespo CJ, Wactawski-Wende J. Health behaviors and other characteristics of women on hormone therapy: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Menopause 2004;11:536–42.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grants (HL43851, CA47988) from the National Institutes of Health and by philanthropic support from Elizabeth and Alan Doft and their family. The abstract was presented at the 2nd International Conference on Women, Heart Disease and Stroke, February 16–19, 2005 (Circulation 2005;111: e40–e88).

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Huang has no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Buring has received investigator-initiated research funding and support from Dow Corning Corporation, research support for pills and/or packaging on NIH-funded studies from Bayer Health Care and the Natural Source Vitamin E Association, honoraria from Bayer for speaking engagements, and she serves on an external scientific advisory committee for a study by Procter & Gamble. Dr. Ridker has received investigator-initiated research support from Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dade-Behring, Novartis, Pharmacia, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Variagenics. Dr. Ridker is listed as a coinventor on patents held by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital that relate to the use of inflammatory biomarkers in cardiovascular disease and has served as a consultant to Schering-Plough, Sanofi-Aventis, Astra Zeneca, Isis Pharmaceutical, and Dade-Behring. Dr. Glynn has received investigator-initiated research support from Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Py.A., Buring, J.E., Ridker, P.M. et al. Awareness, Accuracy, and Predictive Validity of Self-Reported Cholesterol in Women. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 606–613 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0144-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0144-1