Abstract

BACKGROUND

Racial and socioeconomic disparities have been identified in osteoporosis screening.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether racial and socioeconomic disparities in osteoporosis screening diminish after hip fracture.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study of female Medicare patients.

SETTING

Entire states of Illinois, New York, and Florida.

PARTICIPANTS

Female Medicare recipients aged 65–89 years old with hip fractures between January 2001 and June 2003.

MEASUREMENTS

Differences in bone density testing by race/ethnicity and zip-code level socioeconomic characteristics during the 2-year period preceding and the 6-month period following a hip fracture.

RESULTS

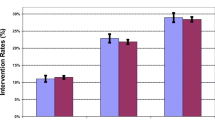

Among all 35,681 women with hip fractures, 20.7% underwent bone mineral density testing in the 2 years prior to fracture and another 6.2% underwent testing in the 6 months after fracture. In a logistic regression model adjusted for age, state, and comorbidity, women of black race were about half as likely (RR 0.52 [0.43, 0.62]) and Hispanic women about 2/3 as likely (RR 0.66 [0.54, 0.80]) as white women to undergo testing before their fracture. They remained less likely (RR 0.66 [0.50, 0.88] and 0.58 [0.39, 0.87], respectively) to undergo testing after fracture. In contrast, women residing in zip codes in the lowest tertile of income and education were less likely than those in higher-income and educational tertiles to undergo testing before fracture, but were no less likely to undergo testing in the 6 months after fracture.

CONCLUSIONS

Racial, but not socioeconomic, differences in osteoporosis evaluation continued to occur even after Medicare patients had demonstrated their propensity to fracture. Future interventions may need to target racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities differently.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Neuner JM, Binkley N, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Bone density testing in older women and its association with patient age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):485–9.

Solomon DH, Brookhart MA, Gandhi TK, et al. Adherence with osteoporosis practice guidelines: a multilevel analysis of patient, physician, and practice setting characteristics. Am J Med. 2004;117(12):919–24.

Miller RG, Ashar BH, Cohen J, et al. Disparities in osteoporosis screening between at-risk African-American and white women. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):847–51.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002.

Cauley JA, Lui L-Y, Ensrud KE, et al. Bone mineral density and the risk of incident nonspinal fractures in black and white women. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2102–8.

Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, et al. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(2):185–94.

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280(24):2077–82.

Harris S, Watts N, Genant H, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–52.

Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Broll J, et al. Effect of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. The Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(22):1437–43.

Colon-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, Pieper C, et al. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(11):879.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004.

Hodgson SF, Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2001 medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2001;7(4):293–312.

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physicians’ Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 1999.

NIH. Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. NIH Consensus Statement Online March 27–29 2000. (Accessed 2006 November 21); 17(1):1–36.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Data User’s Reference Guide. 2000. Available at http://www.resdac.umn.edu/Medicare/data_file_descriptions.asp#rif. (Accessed 2007 June 2).

Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(7):703–14.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Technology Assessment. Number 6: Bone Densitometry: Patients with Asymtomatic Hyperparathyroidism. AHRQ Publication No. 96-0004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995.

Bates DW, Black DM, Cummings SR. Clinical use of bone densitometry: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1898–900.

Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Katz JN, Mogun H, Avorn J. Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Am J Med. 2003;115(5):398–400.

Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10.

Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence from national samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(5):475–86.

Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, MacKenzie C. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–67.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1.

Mudano AS, Casebeer L, Patino F, et al. Racial disparities in osteoporosis prevention in a managed care population. South Med J. 2003;96(5):445–51.

Wilkins CH, Goldfeder JS. Osteoporosis screening is unjustifiably low in older African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(4):461–7.

Jacobsen SJ, Goldberg J, Miles TP, Brody JA, Stiers W, Rimm A. Race and sex differences in mortality following fracture of the hip. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(8):1147–50.

Furstenberg A, Mezey M. Differences in outcome between black and white elderly hip fracture patients. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(10):931–8.

Burgess DJ, Fu SS, van Ryn M. Why do providers contribute to disparities and what can be done about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1154–9.

Balsa AI, McGuire TG. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. J Health Econ. 2003;22(1):89–116.

Pathman D, Fowler-Brown A, Corbie-Smith G. Differences in access to outpatient medical care for black and white adults in the Rural South. Med Care. 2006;44(5):429–38.

U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment. Hip Fracture Outcomes in People Age 50 and Over—Background Paper. OTA-BP-H-120. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994.

Grisso JA, Kelsey JL, Strom BL, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in black women. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(22):1555–9.

Barrett-Connor E, Siris ES, Wehren LE, et al. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in women of different ethnic groups. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(2):185–94.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–88.

Lurie N. Health disparities—less talk, more action. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):727–9.

Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ. 1998;316(7125):133–7.

Harrington JT, Barash HL, Day S, Lease J. Redesigning the care of fragility fracture patients to improve osteoporosis management: a health care improvement project. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(2):198–204.

Acknowledgements

Presented at the 28th Annual Society of General Internal Medicine meeting in New Orleans, LA, May 12–14 2005. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, which had no role in determining the study design, analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the paper for publication. Grant support: PHS NIA #K08-AG021631 to Dr. Neuner.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Inclusion criteria:

-

IC 1

Continously enrolled in non-health maintenance organization, Medicare parts A and B January 1999 to December 2003

-

IC 2

White, black, and Hispanic females

-

IC 3

Continuously residing in Florida, Illinois, or New York from 1999 to 2003

-

IC 4

Aged +65 years old as of January 1 1999

-

IC 5

Residential zip code available and corresponding U.S. Census data available

-

IC 6

Each patient has at least one of the following:

-

(a)

An inpatient SAF claim with a hip/femoral shaft fracture discharge diagnosis

-

(b)

An inpatient SAF claim with a hip fracture hospital procedure

-

(c)

An inpatient SAF claim with a hip/femoral shaft fracture admission diagnosis and/or a carrier SAF claim with a hip/femoral shaft fracture diagnosis

-

(d)

A carrier SAF claim with a hip/femoral shaft fracture physician identification procedure

-

(e)

A carrier SAF claim with a hip/femoral shaft fracture physician confirmation procedure

-

(a)

Exclusion criteria:

-

EC 1

Care of anthroplasty, old fracture, or other bone disease

-

EC 2

Orthopedic surgeon claims present with no identification nor confirmation procedures

-

EC 3

Hospital procedure only

-

EC 4

Hospital admission diagnosis and/or physician diagnosis only

-

EC 5

Physician confirmation procedure only

-

EC 6

A hip fracture found prior to January 1 2001

-

EC 7

No hip fracture found during the period from January 1 2001 to June 30 2003

-

EC 8

Age at time of fracture >90 years

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neuner, J.M., Zhang, X., Sparapani, R. et al. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Bone Density Testing Before and After Hip Fracture. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 1239–1245 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0217-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0217-1