Abstract

Background

Recruiting patients into clinical research protocols is challenging. Electronic medical record (EMR) systems capable of prompting clinicians may facilitate enrollment.

Objective

To compare an EMR-based clinician prompt versus a wait-room-based case-finding strategy at enrolling patients into a clinical trial.

Design

Cross-sectional comparison of recruitment data from two trials to treat anxiety disorders in primary care. Both studies utilized similar enrollment criteria, intervention strategies, and the same four practice sites and EMR system.

Participants

Patients referred by their (primary care physicians) PCPs in response to an EMR prompt (recruited 1/2005–10/2006), and patients enrolled by research assistants stationed in practice waiting rooms (7/2000–4/2002).

Measurements

Referral counts, patients’ baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

Over a 22-month period, EMR-prompted PCPs referred 794 patients and 176 (22%) met study inclusion criteria and enrolled, compared to 8,095 patients approached by wait room-based recruiters of whom 193 (2.4%) enrolled. Subjects enrolled by EMR-prompted PCPs were more likely to be non-white (23% vs 5%; P < 0.001), male (28% vs 18%; P = 0.03), and have higher anxiety levels than those recruited by wait-room recruiters (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

EMR systems prompting clinicians to refer patients with specific characteristics are an efficient recruitment tool with critical implications for increasing minority participation in clinical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical trials are the gold standard for testing therapies that may improve clinical care. Yet, they often fail to reliably answer the posed hypotheses because of their inability to meet targeted recruitment goals in a timely fashion. Adequate patient enrollment has become even more challenging given new regulations that limit researchers’ ability to approach potential study subjects,1 busy clinicians inability to keep track of ongoing studies, and patient skepticism about the benefits of participating in research. These issues may be more problematic among racial and ethnic minorities who are often underrepresented in clinical trials.2 Novel strategies are necessary to efficiently and systematically screen patients for study protocols without burdening busy clinicians and their practice staff.

Interactive electronic medical record (EMR) systems capable of automatically prompting physicians to provide evidence-based care can improve the safety and effectiveness of health care.3 Yet their effectiveness at promoting subject enrollment into research protocols has been little studied.4–8 This report compares use of an EMR-based electronic physician prompt strategy to a more traditional case-finding method for subject recruitment into two similar trials to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders (PD/GAD) in the primary care setting.

METHODS

We are conducting an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved trial of telephone-based collaborative care for treating PD/GAD at 4 primary care practices within the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The practices participated in our earlier trial of collaborative care for PD/GAD9 and share a common commercially available EMR (EpicCare® Ambulatory Electronic Medical Record, Madison, WI). They include the University’s main urban faculty practice, and one rural and two suburban practices.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) view their patients’ medical information on computer workstations placed in each examination room. The EMR has an integral messaging system that permits PCPs and practice staff to communicate with each other and to document care. Electronic reminders prompt physicians to provide preventive and chronic illness care based on patient age, sex, and medical diagnoses entered into coded EMR fields.

Physician Training

Before the start of patient recruitment into both trials, we conducted training to familiarize PCPs with anxiety and mood disorders, and to inform them of our study procedures. Both trials utilized similar telephone-based collaborative care strategies10 and PCPs received instruction on recognizing anxiety and mood disorders and a copy of our locally adapted treatment guidelines for PD and GAD.10 Before activating our electronic reminders, we provided PCPs with guidance on how to respond to the EMR prompts.

Waitroom Recruitment Strategy

A study recruiter stationed in a practice waiting room administered the PRIME-MD patient questionnaire (PQ)11 to screen patients for the presence of an anxiety disorder. We required that patients with a positive PQ screen have: (a) no obvious dementia, psychotic illness, or unstable medical condition; (b) two or fewer positive responses on the CAGE alcohol screening questionnaire12 embedded within the PQ; and (c) no language or other communication barrier. If so, the recruiter obtained written consent to administer the PRIME-MD Anxiety Module.11 If the patient met DSM-IV criteria for PD and/or GAD, the recruiter confirmed the patient: (a) was not in active treatment with a mental health professional; (b) had no history of bipolar disorder; and (c) had no plans to leave the study practice within the following year. If confirmed, the recruiter consented the patient for our telephone follow-up procedure to determine the severity of their anxiety symptoms. We required at least a moderate level of anxiety symptoms as defined by a score ≥14 on the structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A)13 or ≥7 on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS).14

EMR-based Strategy

We designed our EMR prompt to expose the PCP to a reminder about our study at the time of the clinical encounter for patients aged 18–64 with anxiety, generalized anxiety, panic, or depression entered into their electronic problem list, or if the physician coded one of these syndromes as the encounter diagnosis (Fig. 1). We included depression as a trigger given its 40–50% comorbidity with anxiety, and PCPs greater likelihood to recognize and document mood disorders than anxiety disorders.15,16 The alert was suppressed if bipolar and psychotic disorders were on the electronic problem list. We did not enroll any patients into our trial before activation of our alerts.

We designed our alert to be Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant; instructing PCPs to seek patient permission before forwarding contact information to a study recruiter (Fig. 1). Our research team was unaware of any patient’s identity until the PCP obtained oral consent to release this information. To facilitate our electronic approach, the IRB permitted PCPs to obtain a patient’s verbal consent rather than a signed HIPAA consent to release contact information.

After obtaining verbal consent, the PCP mouse-clicked a hyperlink within the alert that automatically entered the referral on an order list for the encounter. Once the PCP signed the order, an electronic “referral” containing the patient’s name and telephone number was forwarded to a “pool address” from which our research team then attempted to contact the patient. We programmed the prompt to turn off for a 180-day period after the referral, and permanently for patients who enrolled into our trial. However, the alert continued to trigger at subsequent visits if the PCP did not respond to the prompt.

The PCP could also initiate an electronic referral for any patient after obtaining consent by sending an electronic message to our pool address. We periodically reminded PCPs of this easily remembered address during routine training sessions, and through study-specific marketing materials (e.g., pens, mugs, and newsletters).

Within two business days after the PCP encounter, a research assistant telephoned the patient to describe our study, confirm preliminary eligibility criteria, and answer questions. If the patient remained potentially eligible to participate, they met with our study staff in the clinic to provide signed consent and confirm eligibility using similar criteria as our waitroom recruitment strategy.

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline sociodemographic, diagnostic, and symptom severity variables by recruitment strategy using t tests for continuous data and chi-square analyses for categorical data.

RESULTS

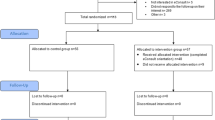

Over a 22-month period (7/00–4/02), staff based in PCP offices approached 8,095 patients, and 193 (2.4%) met all eligibility requirements and agreed to enroll.9 During the first 22 months using the electronic prompts (1/05–10/06), PCPs referred 794 patients, and 176 (22%) met all eligibility criteria and agreed to enroll (Table 1).

The number of electronic referrals generated varied widely across PCPs (range 1–54; median 5). Although PCPs could use the EMR’s messaging system to initiate an electronic referral, we estimate fewer than 5% of referrals were made in this fashion. Patients enrolled through the EMR-based recruitment strategy were more likely to be non-white, male, and have higher levels of anxiety (all p ≤ 0.03) than those enrolled using office-based recruiters (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

EMR systems capable of prompting clinicians to refer patients with specific clinical characteristics represent an efficient recruitment tool with critical implications for increasing minority participation in clinical research. The proportion of non-White study subjects enrolled via the electronic prompts was fivefold higher than that obtained using our traditional case-finding method.

Despite the benefits of EMR-facilitated trial recruitment, there have been few published reports,4–8 and none involving a mental health condition. A prior study compared an EMR-facilitated enrollment strategy to a traditional recruitment method for a diabetes research protocol, reporting a favorable effect of EMR-based prompts over more traditional means. However, it reported no data on study subjects’ sociodemographic or clinical profiles by recruitment method.8

EMR-based recruitment strategies can be applied to other studies seeking to identify patients with specific conditions. They may increase efficiency by reducing the burden imposed on practice staff and study personnel. We utilized approximately 1.75 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff versus 3.5 FTE staff in our earlier trial9 to enroll a similar number of subjects. These efficiencies likely result from: (1) eliminating the need for research assistants to screen patients in practice waiting rooms; (2) transmitting patient referrals to study personnel electronically via the EMR; and (3) evaluating patients more likely to qualify for study enrollment.

The electronic prompt strategy did not require systematic screening of patients for our target conditions. Rather, we trained clinicians to recognize anxiety disorders and on how to respond to our electronic prompt. We were therefore reliant on clinician recognition of targeted conditions and entry of diagnostic codes into the EMR. Indeed, we observed a wide range of referral volume by our PCPs, and these referrals were for more symptomatically anxious patients compared to the wait room strategy. This is likely a result of PCPs documenting the presence of mood and anxiety disorders among the most symptomatic patients.15,17

Our EMR-based recruitment strategy is limited to settings with well-established information systems capable of generating automated alerts. Whereas EMRs are not yet commonly used in medical practices,18 their use is accelerating given national initiatives to reduce medical errors19 and decrease health care costs.20,21 Heightened appreciation of the EMR’s potential to support clinical research could further their adoption into routine clinical care.

We conclude that EMR systems capable of prompting clinicians based on the presence of specific patient characteristics represent a highly efficient recruitment tool for clinical research. The EMR may also have critical implications for enrolling minority subjects and other groups traditionally underrepresented in research protocols.

References

Ness RB. A year is a terrible thing to waste: early experience with HIPAA. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):85–6.

Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–6.

Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–52.

Musen MA, Carlson RW, Fagan LM, Deresinski SC, Shortliffe EH. T-HELPER: automated support for community-based clinical research. Proceedings of the 16th Annual Symposium on Computer Applications in Medical Care 1992, pp 719–23.

Butte AJ, Weinstein DA, Kohane IS. Enrolling patients into clinical trials faster using Real Time Recruiting. Proceedings of AMIA Symposium 2000, pp 111–5.

Afrin LB, Oates JC, Boyd CK, Daniels MS. Leveraging of open EMR architecture for clinical trial accrual. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2003, pp 16–20.

Weiner DL, Butte AJ, Hibberd PL, Fleisher GR. Computerized recruiting for clinical trials in real time. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(2):242–6.

Embi PJ, Jain A, Clark J, Bizjack S, Hornung R, Harris CM. Effect of a clinical trial alert system on physician participation in trial recruitment. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2272–7.

Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, et al. A randomized trial to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1332–41.

Rollman BL, Herbeck Belnap B, Reynolds C, Schulberg H, Shear M. A contemporary protocol for the treatment of panic and generalized anxiety in primary care. Gen Hosp Psych. 2003;25:74–82.

Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56.

Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–7.

Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(4):166–78.

Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–5.

Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Beesdo K, Krause P, Hofler M, Hoyer J. Generalized anxiety and depression in primary care: prevalence, recognition, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 8):24–34.

Kessler RC, Wittchen HU. Anxiety and depression: the impact of shared characteristics on diagnosis and treatment. Introduction. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Supplement 2000(406):5–6.

Tiemens BG, Ormel J, Simon GE. Occurrence, recognition, and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(5):636–44.

Jha AK, Ferris TG, Donelan K, et al. How common are electronic health records in the United States? A summary of the evidence. Health Aff. 2006;25(6):w496–w507.

Johnson MR. Tools and systems for improved outcomes. Institute of Medicine report on healthcare quality. J Outcomes Manage. 2002;6(2):45–8.

Casalino L, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, et al. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. JAMA. 2003;289(4):434–41.

Blumenthal D, Glaser JP. Information technology comes to medicine. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2527–34.

Hamilton M. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. In: Sartorius N, Bant T, eds. Assessment of Depression. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986:143–52.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Rollman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the conceptualization of the described trials, their conduct, and data integrity as Principal Investigator, and for the preparation of this manuscript as its first and corresponding author.

Dr. Herbeck Belnap assisted with the implementation and conduct of both trials, their data collection, and with data analysis.

Dr. Fischer assisted with the development of the EMR prompt and with software and other programming issues related to the EMR system.

Ms. Zhu takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis as statistician.

We also gratefully acknowledge feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript by Herbert C. Schulberg, Ph.D, Professor of Psychiatry, Weil Medical College of Cornell University, and Andre Tylee, M.B.B.S., M.D., Professor of Primary Care Mental Health, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College, London.

All coauthors received a copy of this manuscript and provided Dr. Rollman with their comments on earlier drafts before its submission for editorial review. Neither they, Drs. Schulberg and Tylee, nor Dr. Rollman have any financial disclosures or potential conflicts of interest to report.

EpicCare is a registered trademark of Epic Systems Corporation in the United States and in other countries. We appreciate the Company’s permission to reproduce the screenshot portrayed in Fig. 1.

Role of the Funding Source

All work described was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH09421, initial grant and competing renewal). The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of our study or in the preparation, review, or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Data collected by the trials described in this report have been registered as:ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT00158327 and NCT00102427.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rollman, B.L., Fischer, G.S., Zhu, F. et al. Comparison of Electronic Physician Prompts versus Waitroom Case-Finding on Clinical Trial Enrollment. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 447–450 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0449-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0449-0