Abstract

Background

Little research investigates the role of patient–physician communication in understanding racial disparities in depression treatment.

Objective

The objective of this study was to compare patient–physician communication patterns for African-American and white patients who have high levels of depressive symptoms.

Design, Setting, and Participants

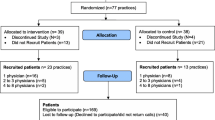

This is a cross-sectional study of primary care visits of 108 adult patients (46 white, 62 African American) who had depressive symptoms measured by the Medical Outcomes Study–Short Form (SF-12) Mental Component Summary Score and were receiving care from one of 54 physicians in urban community-based practices.

Main Outcomes

Communication behaviors, obtained from coding of audiotapes, and physician perceptions of patients’ physical and emotional health status and stress levels were measured by post-visit surveys.

Results

African-American patients had fewer years of education and reported poorer physical health than whites. There were no racial differences in the level of depressive symptoms. Depression communication occurred in only 34% of visits. The average number of depression-related statements was much lower in the visits of African-American than white patients (10.8 vs. 38.4 statements, p = .02). African-American patients also experienced visits with less rapport building (20.7 vs. 29.7 statements, p = .009). Physicians rated a higher percentage of African-American than white patients as being in poor or fair physical health (69% vs. 40%, p = .006), and even in visits where depression communication occurred, a lower percentage of African-American than white patients were considered by their physicians to have significant emotional distress (67% vs. 93%, p = .07).

Conclusions

This study reveals racial disparities in communication among primary care patients with high levels of depressive symptoms. Physician communication skills training programs that emphasize recognition and rapport building may help reduce racial disparities in depression care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–92.

Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2515–23.

Kessler L, Burns B, Shapiro S, Tischler G. Psychiatric diagnoses of medical service users: Evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:18–24.

Leaf P, Livingston M, Tischler G. Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care. 1985;23:1322–37.

Pérez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Muñoz RF, Ying YW. Depression in medical outpatients. Underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–8.

Balsa AL, McGuire TG, Meredith LS. Testing for statistical discrimination in health care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):227–52.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J. Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care. 1992;30(1):67–76.

Magruder-Habib K, Zung WWK, Feussner J, Alling WC, Saunders WB, Stevens HA. Management of general medical patients with symptoms of depression. Gen Hosp Psych. 1989;11:201–10.

Brown C, Schulberg HC, Sacco D, Perel JM, Houck PR. Effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary medical care practice: a post hoc analysis of outcomes for African American and white patients. J Affect Dis. 1999;53:185–92.

Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk for non-detection of mental health problems in primary care? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:381–8.

Commander MJ, Dharan SP, Odell SM, Surtees PG. Access to mental health care in an inner-city health district. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:317–20.

Gallo JJ, Bogner H, Morales KH, Ford DE. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1962–8.

Leo RJ, Sherry C, Jones AW. Referral patterns and recognition of depression among African-American and Caucasian patients. Gen Hosp Psych. 1998;20:175–82.

Wells KB, Katon W, Rogers B, Camp P. Use of minor tranquilizers and antidepressant medication by depressed outpatients: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:694–700.

Lawson WB. Clinical issues in the pharmacotherapy of African-Americans. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32(2):275–81.

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61.

Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui TS. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1997;277:350–6.

Johnson RL, Roter DL, Powe N, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient–physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2081–90.

Tai-Seale M, Bramson R, Drukker D, Hurwicz ML, Ory M, Tai-Seale T, Street R Jr, Cook MA. Understanding primary care physicians’ propensity to assess elderly patients for depression using interaction and survey data. Med Care. 2005;43(12):1217–24.

Sleath B, Rubin RH. Gender, ethnicity, and physician-patient communication about depression and anxiety in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):243–52.

Kales HC, Mellow AM. Race and depression: does race affect the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression? Geriatrics. 2006;61(5):18–21, (review).

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–15.

Ware JE Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey. Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Gill SC, Butterworth P, Rodgers B, Mackinnon A. Validity of the mental health component scale of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (MCS-12) as measure of common mental disorders in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2007;152:63–71.

Ware JE, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SF. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, 1994.

Walsh TL, Homa K, Hanscom B, Lurie J, Sepulveda MG, Abdu W. Screening for depressive symptoms in patients with chronic spinal pain using the SF-36 Health Survey. Spine J. 2006;6(3):316–20.

Silveira E, Taft C, Sundh V, Waern M, Palsson S, Steen B. Performance of the SF-36 Health Survey in screening for depressive and anxiety disorders in an elderly female Swedish population. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1263–74.

Amir M, Lewin-Epstein N, Becker G, Buskila D. Psychometric properties of the SF-12 (Hebrew version) in a primary care population in Israel. Med Care. 2005;40:918–28.

Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–9, (review).

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Jenkinson C, Chandola T, Coulter A, et al. An assessment of the construct validity of the SF-12 summary scores across ethnic groups. J Public Health Med. 2001;23(3):187–94.

Krupat E, Frankel R, Stein T, Irish J. The four habits coding scheme: validation of an instrument to assess clinicians’ communication behavior. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(1):38–45.

Zandbelt LC, Smets EM, Oort FJ, de Haes HC. Coding patient-centered behaviour in the medical encounter. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(3):661–71.

Roter DL, Larson S. The relationship between residents’ and attending physicians’ communication during primary care visits: an illustrative use of the Roter Interaction Analysis System. Health Commun. 2001;13:33–48.

Mead N, Bower P. Measuring patient-centeredness: a comparison of three observation-based instruments. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:71–80.

Stata Statistical Software Version 9, College Station Tex: Stata Corporation 2005.

Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130.

Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe N, Nelson C, Ford DE. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient–physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–89.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Rand CS. Communication of affect between patient and physician. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(1):18–30.

van Wieringen JC, Harmsen JA, Bruijnzeels MA. Intercultural communication in general practice. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12(1):63–8.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker R, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–84.

Worrall G, Angel J, Chaulk P, Clarke C, Robbins M. Effectiveness of an educational strategy to improve family physicians’ detection and management of depression: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 1999;161(1):37–40.

Robinson JW, Roter DL. Counseling by primary care physicians of patients who disclose psychosocial problems. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(9):698–705.

Moral R, Alamo MM, Jurado MA, de Torres LP. Effectiveness of a learner-centered training programme for primary care physicians in using a patient-centered consultation style. Fam Pract. 2001;18(1):60–3.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented, in part, at the 15th NIMH International Conference on Mental Health Services, Washington DC, April 2, 2002 and the 25th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Atlanta, GA, May 3, 2002. This work was supported by grants from the Commonwealth Fund, the Aetna Managed Care and Research Forum, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS13645).

Disclaimer

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers, or staff.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghods, B.K., Roter, D.L., Ford, D.E. et al. Patient–Physician Communication in the Primary Care Visits of African Americans and Whites with Depression. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 600–606 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0539-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0539-7