Abstract

Background

Physician treatment of cardiovascular risk factors may be affected by specific types of patient comorbidities.

Objectives

To examine the relationship between discordant comorbidities and LDL-cholesterol management in hypertensive patients not previously treated with lipid-lowering therapy; to determine whether the presence of cardiovascular (concordant) conditions mediates this relationship.

Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 1,935 hypertensive primary care patients (men >45 years of age, women >55 years of age) with documented elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and no lipid-lowering therapy at baseline. The outcome was guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management defined as optimal value on repeat LDL cholesterol testing or initiation of lipid-lowering therapy. Using generalized estimating equations (GEE), we examined the association of concordant and discordant comorbidities with guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management over a 2-year follow-up period, adjusting for patient characteristics.

Results

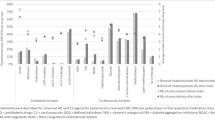

Guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management was achieved in 1,236 patients (64%). In the fully adjusted model, each additional discordant condition resulted in a 19% lower adjusted odds ratio of guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management (p < 0.001) when compared with no discordant conditions. The dampening effect of discordant conditions on guideline-consistent management persisted even in the presence of concordant conditions, but each additional concordant condition was associated with a 37% increase in the adjusted odds of guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In this cohort of hypertensive primary care patients, the number of conditions discordant with cardiovascular risk was strongly negatively associated with guideline-consistent hyperlipidemia management even in patients at the highest risk for cardiovascular events and cardiac death.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al.. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.[see comment]. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

Higashi TMD, Shekelle PGMDP, Solomon DHMD, et al. The Quality of Pharmacologic Care for Vulnerable Older Patients. [Miscellaneous]. In: Annals of Internal Medicine May 4 2004;140(9):714–720.

Rosenthal MB, Frank RG. What is the empirical basis for paying for quality in health care? Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):135–57.

Werner RM, Asch DA. Clinical concerns about clinical performance measurement. Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5(2):159–63.

Hayward RA. Performance measurement in search of a path.[comment]. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(9):951–3.

McMahon LF Jr., Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Physician-level P4P–DOA? Can quality-based payment be resuscitated? American Journal of Managed Care. 2007;13(5):233–6.

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance.[see comment]. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–24.

Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status.[see comment]. JAMA. 2006;295(16):1935–40.

Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST Jr., Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2870–4.

Higashi T, Wenger NS, Adams JL, et al.. Relationship between number of medical conditions and quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2496–504.

Glynn RJ, Monane M, Gurwitz JH, Choodnovskiy I, Avorn J. Aging, comorbidity, and reduced rates of drug treatment for diabetes mellitus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(8):781–90.

Chaudhry SI, Berlowitz DR, Concato J. Do age and comorbidity affect intensity of pharmacological therapy for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus?[see comment]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1214–6.

McLaughlin TJ, Soumerai SB, Willison DJ, et al.. The effect of comorbidity on use of thrombolysis or aspirin in patients with acute myocardial infarction eligible for treatment.[see comment]. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):1–6.

Min LC, Wenger NS, Fung C, et al.. Multimorbidity is associated with better quality of care among vulnerable elders.[see comment]. Med Care. 2007;45(6):480–8.

Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatr. 2002;159(9):1584–90.

Heflin MT, Oddone EZ, Pieper CF, Burchett BM, Cohen HJ. The effect of comorbid illness on receipt of cancer screening by older people.[see comment]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1651–8.

Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–31.

Piette JD, Richardson C, Valenstein M. Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: the case of diabetes and depression. American Journal of Managed Care. 2004;10(2 Pt 2):152–62.

Expert Panel on Detection EaToHBCiA. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III).[see comment]. JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–97.

Anonymous. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure.[see comment][erratum appears in Arch Intern Med 1998 Mar 23;158(6):573]. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(21):2413–46.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data.[see comment]. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

Kerr EA, Heisler M, Krein SL, et al.. Beyond comorbidity counts: how do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients’ treatment priorities and self-management?[see comment]. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1635–40.

Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hiatt L, et al.. Quality of care for hypertension in the United States. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2005;5(1):1.

Rodondi N, Peng T, Karter AJ, et al.. Therapy modifications in response to poorly controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.[see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):475–84.

Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Hirsch IB. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psych. 2003;25(4):246–52.

Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases.[see comment]. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(21):1516–20.

Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Makki F, Kerr EA. The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients’ self-management.[see comment]. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):65–70.

Fisher ES, Whaley FS, Krushat WM, et al.. The accuracy of Medicare’s hospital claims data: progress has been made, but problems remain. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(2):243–8.

Iezzoni LI. Using administrative diagnostic data to assess the quality of hospital care. Pitfalls and potential of ICD-9-CM. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1990;6(2):272–81.

Jollis JG, Ancukiewicz M, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Muhlbaier LH, Mark DB. Discordance of databases designed for claims payment versus clinical information systems. Implications for outcomes research.[see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(8):844–50.

Romano PS, Mark DH. Bias in the coding of hospital discharge data and its implications for quality assessment. Med Care. 1994;32(1):81–90.

Farley JF, Harley CR, Devine JW. A comparison of comorbidity measurements to predict healthcare expenditures. Am J Managed Care. 2006;12(2):110–9.

Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Meenan RT, Bachman DJ, O’Keeffe Rosetti MC. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model.[see comment]. Med Care. 2003;41(1):84–99.

Gilmer T, Kronick R, Fishman P, Ganiats TG. The Medicaid Rx model: pharmacy-based risk adjustment for public programs. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1188–202.

Perkins AJ, Kroenke K, Unutzer J, et al.. Common comorbidity scales were similar in their ability to predict health care costs and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57101040–8.

Pietz K, Petersen LA. Comparing self-reported health status and diagnosis-based risk adjustment to predict 1- and 2 to 5-year mortality. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):629–43.

Kerr EA, Smith DM, Hogan MM, et al.. Building a better quality measure: are some patients with ‘poor quality’ actually getting good care? Med Care. 2003;41(10):1173–82.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Supported by Pfizer Inc. and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program

Conflicts of Interest

Funding for this project was provided by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Inc. The University of Pennsylvania provided the mechanism for administration of this grant. Investigators at the University of Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania State University performed the analyses. By contract, the investigators retain the right to publish results and manuscripts without approval from Pfizer Inc. Dr. Lagu is funded by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 36.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lagu, T., Weiner, M.G., Hollenbeak, C.S. et al. The Impact of Concordant and Discordant Conditions on the Quality of Care for Hyperlipidemia. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1208–1213 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0647-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0647-4