Abstract

Objective

We compared the quality of care for cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related risk factors for patients diagnosed with and without mental disorders.

Methods

We identified all patients included in the fiscal year 2005 (FY05) VA External Peer Review Program’s (EPRP) national random sample of chart reviews for assessing quality of care for CVD-related conditions. Using the VA’s National Psychosis Registry and the National Registry for Depression, we assessed whether patients had received diagnoses of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychoses) or depression during FY05. Using multivariable logistic regression and generalized estimating equation analyses, we assessed patient and facility factors associated with receipt of guideline concordant care for hypertension (total N = 24,016), hyperlipidemia (N = 46,430), and diabetes (N = 10,943).

Results

Overall, 70% had good blood pressure control, 90% received a cholesterol (hyperlipidemia) screen, 77% received a retinal exam for diabetes, and 63% received recommended renal tests for diabetes. After adjustment, compared to patients without SMI or depression, patients with SMI were less likely to be assessed for CVD risk factors, notably hyperlipidemia (OR = 0.58; p < 0.001), and less likely to receive recommended follow-up assessments for diabetes: foot exam (OR = 0.68; p < 0.001), retinal exam (OR = 0.65; p < 0.001), or renal testing (OR = 0.64; p < 0.001). Patients with depression were also significantly less likely to receive adequate quality of care compared to non-psychiatric patients, although effects were smaller than those observed for patients with SMI.

Conclusions

Quality of care for major chronic conditions associated with premature CVD-related mortality is suboptimal for VA patients with SMI, especially for procedures requiring care by a specialist.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

Mental disorders are prevalent1 and are associated with substantial functional impairment, healthcare costs, and premature mortality.2–4 In particular, serious and persistent mental illnesses (i.e., SMI, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other nonorganic psychotic disorders) and unipolar depression are leading causes of disability in the US.2,5

Much of the disability in patients with mental disorders is attributed to co-occurring general medical conditions.6 Many of these conditions, notably diabetes (28%), hypertension (30%), and hyperlipidemia (23%), occur more frequently in patients with mental disorders than non-psychiatric patients7 and are the leading risk factors for cardiovascular disease [CVD]8. CVD is the most common condition associated with premature death in patients with mental disorders.3 Undertreatment of CVD-related conditions may lead to adverse outcomes in patients with mental disorders. The problem is exacerbated with increased use of atypical antipsychotic medications, which have been associated with CVD-related risk factors including weight gain and diabetes.9

Measures of quality of care that reflect established clinical practice guidelines for managing CVD risk factors can be valuable tools for identifying patient populations at greater risk of poor outcomes. To date, the available evidence regarding appropriate care for CVD-related risk factors has focused primarily on lipid monitoring10 or diabetes outcomes.11,12 In general, the current evidence regarding quality of care for patients with and without mental disorders has been mixed, with some studies suggesting equitable care for procedures involving screening13 but potential disparities when care involves more complex procedures or specialty services.14 Moreover, these studies were conducted prior to the widespread use of atypical antipsychotic medications and did not control for patient factors, notably race/ethnicity or medical comorbidity.

There is little current knowledge regarding whether patients with mental disorders are receiving guideline-based quality of care for common CVD-related risk factors. Moreover, comparisons of quality of care have been limited to SMI or depression only, with no comparisons in quality between these two diagnostic groups. Patients with SMI may be especially vulnerable to poor quality of care as they primarily receive services in the mental health specialty sector,15 while depression is one of the most common mental disorders treated in primary care.16 The purpose of this study is to compare the quality of care for CVD-related risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes) among patients with SMI, depression, or no psychiatric diagnosis.

METHODS

This study is based on a national random sample of VA patients with medical record reviews of quality of care for CVD-related risk factors in fiscal year (FY) 2005 based on the VA’s External Peer Review Program (EPRP). Using the VA’s National Psychosis Registry (NPR) and National Depression Registry (NARDEP),17 we then identified veterans within the FY2005 EPRP sample who also had a diagnosis of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, other psychosis) or unipolar depression in FY 2004 or 2005 (See Table 1 for details regarding psychiatric definitions). Developed by the VA Serious Mental Illness Treatment and Evaluation Center (SMITREC), the NPR is an ongoing national administrative database of all veterans with an ICD-9 diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other non-organic psychoses, and NARDEP includes all VA patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or other depression diagnosis.

EPRP conducts a national random sample of over 44,000 patient medical records per fiscal year. Trained nurses review these records using a standard protocol for measuring quality of care medical conditions (See Table 2 footnotes for details regarding EPRP chart sampling process). We compared the quality of care among patients in the EPRP sample who were diagnosed with SMI or depression with the remaining EPRP sample without a psychiatric (SMI or depression) diagnosis. We included other depression diagnoses in order to identify patients with substantial depressive symptoms but whose providers were reluctant to label them as having major depression.18 We separate out those diagnosed with SMI from those diagnosed with depression because SMI is considered the more disabling diagnosis and because19 there have been no studies directly comparing quality of care between these groups. Moreover, site of care may vary by diagnosis, and hence, the probability of receiving adequate quality of care. Persons with depression are often primarily seen in the general medical setting,16 while those with SMI are often managed in the mental health specialty setting.15

Quality Measures

We focused on patient-level quality measures (processes and clinical outcomes) available in EPRP that reflect care for common CVD-related risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes) in accordance with accepted clinical practice guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association.20,21 For hypertension, quality measures included poor hypertension control (blood pressure ≥160/100) and good hypertension control (blood pressure ≤140/90); for hyperlipidemia measures included receipt of a cholesterol screening test and low density lipoprotein <100 among patients with diabetes, and for patients with diabetes, measures included receipt of a foot exam, eye exam, renal test, and HbA1C <9 (see Table 2 for details concerning each measure). Because recommended LDL levels for patients with diabetes may vary depending on the guideline, EPRP included additional indicators that reflect alternate cutpoints for LDL control: <130 or <120 mg/ml. We included intermediate outcome measures as well as process measures because each constitutes part of a comprehensive picture of quality of care.22

Analyses

Multivariate logistic regression and generalized estimating equation analyses were used to determine the probability of receiving processes of care or achieving clinical outcomes for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status (dichotomized as married or widowed versus never married, divorced, or single), substance use disorder diagnosis, medical comorbidity (Charlson score)23, and facility. We chose to adjust for these factors because they were found in prior studies to be the most strongly associated with receiving adequate quality of care in patients with mental disorders.12,13,24 Patients diagnosed with both depression and SMI were classified as having SMI given that SMI is considered to be more debilitating.19 The reference group was defined as having no SMI or depression diagnosis. Consistent with prior studies, we categorized race as Black versus non-Black because disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders is greatest for this group.25,26. We reported the independent effect of race (Black versus non-Black) and the interaction effect between race (Black) and SMI and depression diagnosis, given that race has been shown to influence both SMI diagnosis and quality of care.25,27 Statistical tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method, with a level of significance set to p < 0.00625 based on eight outcomes.

RESULTS

The overall study populations for the hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes cohorts reflect the VA patient population,17 with the vast majority being male and older (Table 1). Patients with SMI were younger, more likely female, more likely Black, less likely married, more likely to have a substance use disorder diagnosis, and had a higher Charlson score (Table 1).

Bivariate analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in quality of care for hypertension, and the majority (72–73%) had good blood pressure control. For hyperlipidemia, over 90% were screened (lipid panel), yet only slightly over half of patients diagnosed with diabetes had an LDL of <100 mg/ml (Table 2). For the diabetes-specific indicators, the majority received a foot or retinal exam, but patients with SMI as a group had a somewhat lower probability of receiving either exam (Table 2).

Bivariate results revealed that Blacks were more likely to have a blood pressure of ≥160/100 mmHg compared to non-Blacks (respectively 10.0% vs. 7.3%, p < 0.001), less likely to have a blood pressure of ≤140/90 mmHg (67.0% vs. 74.0%, p < 0.001), slightly less likely to be screened for hyperlipidemia (92.4% vs. 94.1%, p < 0.001), and among those with diabetes, less likely to have an LDL of <100 (76.2% vs. 81.8%, p < 0.001). For the diabetes indicators, Blacks were more likely to have a HbA1C level of >9 (22.1% vs. 14.2%, p < 0.001).

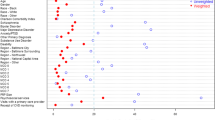

After adjusting for age, gender, race, interaction between race and SMI and depression diagnosis, marital status, any substance use disorder diagnosis, Charlson comorbidity score, and facility, compared to VA patients without SMI or depression (Table 3), those with SMI were 42% less likely to be assessed for CVD risk factors, notably screening for hyperlipidemia (OR = 0.58; p < 0.001). Patients with SMI were also 32–36% less likely to receive recommended follow-up treatment for diabetes, notably foot exam (OR = 0.68; p < 0.001), retinal exam (OR = 0.65; p < 0.001), or renal testing (OR = 0.64; p < 0.001). In terms of the clinical significance of these adjusted findings, most represented medium effect sizes based on standard definitions (e.g., OR < 0.7, or at least 30% less likely to receive care).28

Patients with depression were 26% less likely to receive renal testing for diabetes after adjustment (OR = 0.74; p < 0.001). For these patients, there were trends toward having worse quality and outcomes for hyperlipidemia and diabetes care (e.g., foot exam), but these findings were not significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table 3). Overall, effect sizes were smaller overall for those with depression than for patients with SMI (i.e., odds ratios closer to 1 than for SMI), indicating less clinical significance (Table 3).

No statistically significant differences were observed for quality of care for hypertension among patients with SMI or depression. Intermediate outcomes of care for hyperlipidemia and diabetes (LDL and HbA1C levels, respectively) were similar among patients with and without mental disorders. Similar results were found when different LDL cutpoints were applied (e.g., <120, <130; data not shown). Blacks compared to non-Blacks were less likely to have blood pressure ≤140/90 (OR = 0.74; p < 0.001). No statistically significant interaction effects were observed in our sample (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

To date this is the first study to comprehensively assess quality of care for CVD-related risk factors in both depression and SMI compared to a non-psychiatric control group. In contrast, prior studies did not control for the effects of race or comorbidity, or primarily focused on care for patients with SMI only13 and did not compare quality of care to those with depression, one of the most common diagnoses seen in primary care settings.

Overall, we found that the majority of VA patients in the EPRP FY 2005 sample received adequate quality of care. Our overall findings reflect prior studies,29,30 which found that nationally, the VA performed better than non-VA healthcare organizations on performance measures for hypertension (78% vs. 64%), hyperlipidemia (64% vs. 53%), and diabetes (70% vs. 57%) than did non-VA care settings.30 Differences in quality of care in the VA have been attributed to organizational attributes not universally found in non-VA settings, including electronic medical record use, single payer structure, and widespread application of performance measures to benchmark quality of care nationally.30

Quality of care for intermediate clinical outcomes (blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein, and HbA1C levels) was similar among patients with SMI, depression, or no psychiatric diagnosis, reflecting findings from previous VA studies.12 Nonetheless, we found that patients with SMI were the least likely to receive adequate processes of care for CVD-related conditions compared to those with depression or no psychiatric diagnosis, notably for hyperlipidemia screening and routine follow-up assessments recommended for diabetes (foot exam, retinal exam, and renal testing). These results remained robust even after controlling for race, the interaction between race and diagnosis, and comorbidity.

These observed gaps in processes of care for patients with SMI were also clinically significant, as these patients were 32–42% less likely to receive care for these conditions. With the exception of renal testing, effect sizes for differences in quality between depressed and non-psychiatric patients were smaller, indicating that they were less clinically significant than differences observed for patients with SMI.

For patients with SMI, inadequate processes of care (screening and follow-up care for CVD-related conditions) over time can be problematic because lack of medical attention could lead to adverse medical consequences (e.g., vision problems, amputations)8 or mortality.31 Moreover, the percentage of patients with SMI and poor intermediate CVD risk-related clinical outcomes is likely an underestimate, given that widespread use of atypical antipsychotic medications did not occur until after 2005.

Our observed gaps in processes of care for CVD-related conditions among patients with SMI could be attributable to patient, provider, and/or system-level factors, including location of care, lack of coordination and stigma.29,30 Potential disparities in processes of care may be greater for patients with SMI than for those with depression because they are more likely to be exclusively treated in mental health settings. Our findings regarding processes of diabetes care contrast with earlier EPRP-based research suggesting that quality of care for diabetes was comparable among VA patients with and without SMI.11 In contrast to our study, prior studies were based on past EPRP cohorts (e.g., 2001–03), which only included patients receiving care from outpatient general medical clinics and not from mental health outpatient clinics. In FY2005, the EPRP sampling frame was expanded to include mental health outpatients, where the majority of patients with SMI receive care.15 Many patients with SMI consider the mental health clinic their “home” site for care because of the need for more intensive psychiatric services compared to unipolar depression.15 The availability of general medical services may be limited in mental health settings because mental health providers may be less able to perform screenings, provide integrated care in mental health specialty settings, or assist in following up on referrals to medical specialty care.32

Moreover, patients with SMI may have trouble with navigating care across different providers, particularly for general medical services and follow-up care.32 In addition, providers in general medical or specialty medical care (e.g., endocrinology, ophthalmology) may not have the experience, training, or time to accommodate patients with serious mental illness.33 Consistent with our findings, prior evidence suggests that quality of care for certain conditions that require follow-up with specialists or additional procedures was worse for SMI compared to non-SMI veterans, notably for procedures and medications related to myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease.14,31 The stigma of mental illness, particularly SMI, may also preclude patients from seeking care outside the comfort zone that exists in the mental health clinic.

Despite our use of a national sample on quality of care for patients with and without mental disorders, there are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional nature of the analyses preclude us from examining trends in quality of care over time or causal effects of diagnosis on quality of care. Second, EPRP may have excluded some patients with SMI, as those who were exclusively seen within the VA homeless outreach or mental health work therapy programs were not included in the EPRP sample. Nonetheless, excluding these individuals may have led to an underestimation in the gaps in quality of care for VA patients with SMI. In addition, we were unable to control for clinical factors that might influence care-seeking in persons with SMI, including current psychiatric symptoms, or factors that might influence access to medical services, such as the organizational features of general medical services in mental health clinics. The exact location of service for which quality of care was ascertained (e.g., within mental health versus general medical clinics) was unavailable in the EPRP dataset, and hence, we were unable to determine whether quality varied by treatment setting. Nonetheless, we feel that for quality to improve for veterans with SMI, an overall facility-level quality measure is necessary in order to hold all providers at that facility accountable for improving quality of care for veterans with mental disorders, regardless of the location of their care. Finally, the focus on VA patients may potentially limit the generalizability of our findings.

Overall, our results suggest that the quality of care for CVD-related chronic conditions is suboptimal among patients with SMI, particularly for care involving contacts with medical specialists. Providers and healthcare leaders should consider efforts to improve access and continuity of medical treatment for persons with SMI. Promising treatment models that have been found to be effective within the VA setting include co-location of general medical providers in mental health clinics34 and the Chronic Care Model adapted to address medical care self-management for persons with chronic mental illness.35 The VA’s national infrastructure and electronic medical record system can facilitate the further dissemination of these treatment models across a wider range of VA facilities. Outside the VA, additional efforts are needed to address the administrative and financial separation of mental health and physical health care in order to improve integration of care for persons with SMI. State-level efforts (i.e., Medicaid) to allow for reimbursement of medical services in mental healthcare settings and behavioral management of CVD risk show promise in facilitating access to medical care for vulnerable persons with mental disorders. Still, the stigma of mental illness is a common barrier across VA and non-VA settings, and can especially lead to delays in medical care-seeking and follow-up for persons with SMI. Efforts to address the stigma barrier include improved education of general medical providers in managing patients with SMI, coupled with additional education for patients on managing CVD risk.

References

Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of US workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1561–8.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy-lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–3.

Hennekens C. Increasing global burden of cardiovascular disease in general populations and patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:4–7.

Harris E, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11–53.

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA. 2003;289:3135–44.

Simon GE, Unutzer J. Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1303–8.

Sokal J, Messias E, Dickerson FB, et al. Comorbidity of medical illnesses among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:421–7.

Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2003;290:898–904.

Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(Suppl 1):1–93.

Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:145–51.

Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1584–90.

Krein SL, Bingham CR, McCarthy JF, et al. Diabetes treatment among VA patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1016–21.

Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40:129–36.

Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction [see comments] 1 31. JAMA. 2000;283:506–11.

Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Locus of mental health treatment in an integrated service system 13. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:890–2.

Coyne JC. Interventions for treatment of depression in primary care. JAMA. 2004;291:2814–6.

Blow F, McCarthy J, Valenstein M. Care in the VHA for Veterans with Psychosis: FY2005. First Annual Report on Veterans with Psychoses. 2005

Rost K, Smith R, Matthews DB, et al. The deliberate misdiagnosis of major depression in primary care. [see comments.]. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:333–7.

Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med. 1998;4:1241–3.

Pickering T, Hall J, Appel L, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–16.

American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004:267–72.

McGlynn EA. Introduction and overview of the conceptual framework for a national quality measurement and reporting system. Med Care. 2003;41:I1–7.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation 3. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, et al. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1159–80.

Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS, Han X, et al. Racial differences in the treatment of veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1549–55.

Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS, Pincus H, et al. Clinical, psychosocial, and treatment differences in minority patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:89–97.

Blow FC, Zeber JE, McCarthy JF, et al. Ethnicity and diagnostic patterns in veterans with psychoses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:841–51.

Wickens T. Multiway Contingency Tables Analysis for the Social Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989.

Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–81.

Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–45.

Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders 63. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:565–72.

Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Aff. 2006;25:659–69.

Koran LM, Sox HC Jr, Marton KI, et al. Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients. I. Results in a state mental health system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:733–40.

Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial 4. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:861–8.

Kilbourne AM NA, Drill L, Cooley S, Post EP, Bauer MS. Service delivery in older patients with bipolar disorder: a review and development of a medical care model. Bipolar Disorders 2008;(in press 2008)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. We would like to acknowledge the VA Office of Quality and Performance for providing access to EPRP data (DUA #05–024).

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kilbourne, A.M., Welsh, D., McCarthy, J.F. et al. Quality of Care for Cardiovascular Disease-related Conditions in Patients with and without Mental Disorders. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1628–1633 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0720-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0720-z