Abstract

BACKGROUND

Physical examination teaching using actual patients is an important part of medical training. The patient experience undergoing this type of teaching is not well-understood.

OBJECTIVE

To understand the meaning of physical examination teaching for patients.

DESIGN

Phenomenological qualitative study using semi-structured interviews.

PARTICIPANTS

Patients who underwent a physical examination-based teaching session at an urban Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

APPROACH

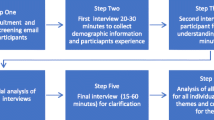

A purposive sampling strategy was used to include a diversity of patient teaching experiences. Multiple interviewers triangulated data collection. Interviews continued until new themes were no longer heard (total of 12 interviews). Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Coding was performed by two investigators and peer-checked. Themes were identified and meanings extracted from themes.

KEY RESULTS

Seven themes emerged from the data: positive impression of students; participation considered part of the program; expect students to do their job: hands-on learning; interaction with students is positive; some aspects of encounter unexpected; range of benefits to participation; improve convenience and interaction. Physical examination teaching had four possible meanings for patients: Tolerance, Helping, Social, and Learning. We found it possible for a patient to move from one meaning to another, based on the teaching session experience.

CONCLUSIONS

Physical examination teaching can benefit patients. Patients have the potential to gain more value from the experience based on the group interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

LaCombe MA. On bedside teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:217–20.

Reichsman F, Browning FE, Hinshaw JR. Observations of undergraduate clinical teaching in action. Acad Med. 1964;39:147–63.

Collins GF, Cassie JM, Daggett CJ. The role of the attending physician in clinical training. J Med Educ. 1978;53:429–31.

Miller M, Johnson B, Greene HL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:646–8.

Chuang CH, Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105–10.

Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Impediments to bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1998;32:159–62.

Ramani S, Orlander JD, Strunin L, Barber TW. Whither bedside teaching: a focus-group study of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78:384–90.

Williams KN, Ramani S, Fraser B, Orlander JD. Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners. Acad Med. 2008;83:257–64.

Janick RW, Fletcher KE. Teaching at the bedside: a new model. Medical Teacher. 25:127–30.

Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen M, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1150–5.

Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31:341–6.

Fletcher KE, Rankey DS, Stern DT. Bedside interactions from the other side of the bedrail. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):58–61.

Fletcher KE, Furney SL, Stern DT. Patients speak: what’s really important about bedside interactions with physician teams. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):120–7. Spring.

Romano J. Patients’ attitudes and behavior in ward round teaching. J Am Med Assoc. 1941;117(9):664–7.

Mangione S, Nieman LZ, Gracely E, Kaye D. The teaching and practice of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and cardiology training: a nationwide survey. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:47–54.

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing; 2006.

Moustakas C. Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994.

Hartz MB, Beal JR. Patients’ attitudes and comfort levels regarding medical students’ involvement in obstetrics-gynecology outpatient clinics. Acad Med. 2000;75(10):1010–14.

DeWalt DA, Boone RS, Pignone MP. Literacy and its relationship with self-efficacy, trust, and participation in medical decision making. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S27–35.

DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228–39.

VonWagner C, Semmler C, Good A, Wardle J. Health literacy and self-efficacy for participating in colorectal cancer screening: the role of information processing. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):352–7.

Berkman ND, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Sheridan SL, Lohr KN, Lux L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Bonito AJ. Literacy and Health Outcomes. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 87 (Prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016). AHRQ Publication No. 04-E007-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2004.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients who agreed to be interviewed for this study. This work was funded by the non-profit Institute for Clinical Research, Washington, DC.

Presented, in part, at the 2009 SGIM Annual Meeting, Miami, FL.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chretien, K.C., Goldman, E.F., Craven, K.E. et al. A Qualitative Study of the Meaning of Physical Examination Teaching for Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 786–791 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1325-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1325-x