Abstract

Background

Lower mammography screening rates among minority and low income women contribute to increased morbidity and mortality from breast cancer.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of a patient navigation intervention on adherence rates to biennial screening mammography among women engaged in primary care at an inner-city academic medical center.

Design

Quality improvement intervention with a concurrent control group, conducted from February to November of 2008.

Study Subjects

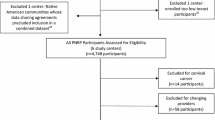

All women in a hospital-based primary care practice aged 51–70 years. Subjects were randomized at the level of their primary care provider, such that half of the patients in the practice received the intervention, while the other half received usual care.

Interventions

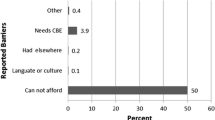

Intervention subjects whose last mammogram was >18 months prior received a combination of telephone calls and reminder letters from patient navigators trained to identify barriers to care. Navigators were integrated into primary care teams and interacted directly with patients, providers, and radiology to coordinate care. Navigators utilized an electronic report to track subjects. Adherence rates to biennial mammography were assessed in intervention and control groups at baseline and post-intervention.

Key Results

A total of 3,895 women were randomized to intervention (n = 1,817) and control (n = 2,078) groups. Mean age was 60, 71% were racial/ethnic minorities, 23% were non-English speaking, and 63% had public or no health insurance. At baseline, there was no difference in mammography adherence between the control and intervention groups (78%, respectively, p = 0.55). After the 9-month intervention, mammogram adherence was higher in the intervention group compared with the control group (87% vs. 76%, respectively, p < 0.001). Except among Hispanic women who demonstrated high rates in both the intervention and control groups (85% and 83%, respectively), all racial/ethnic and insurance groups demonstrated higher adherence in the intervention group.

Conclusions

Patient navigation improves biennial mammography rates for inner city, low income, minority populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer. <http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast Cancer. <http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/race.htm >. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Kagawa-Singer M, Dadia AV, Yu MC, Surbone A. Cancer, culture, and health disparities: time to chart a new course? CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(1):12–39.

Hershman D, McBride R, Jacobson JS, et al. Racial disparities in treatment and survival among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6639–46.

Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman SC, Breen N, Davis WW, Reichman MC. Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987–2005). Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(1):121–31.

Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):541–53.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System summary data quality reports. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services. <www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/quality.htm>. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11(1):59–71.

Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010.

Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):359–67.

Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(1):26–33.

Psooy BJ, Schreuer D, Borgaonkar J, Caines JS. Patient navigation: improving timeliness in the diagnosis of breast abnormalities. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2004;55(3):145–50.

Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):114–24.

Lobb R, Allen JD, Emmons KM, Ayanian JZ. Timely care after an abnormal mammogram among low-income women in a public breast cancer screening program. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(6):521–8.

Dignan MB, Burhansstipanov L, Hariton J, et al. A comparison of two Native American Navigator formats: face-to-face and telephone. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):28–33.

Paskett E, Tatum C, Rushing J, et al. Randomized trial of an intervention to improve mammography utilization among a triracial rural population of women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(17):1226–37.

Han HR, Lee H, Kim MT, Kim KB. Tailored lay health worker intervention improves breast cancer screening outcomes in non-adherent Korean-American women. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(2):318–29.

HEDIS. Technical Specifications, Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2007.

Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A National Patient Navigator Training Program. Health Promot Pract. 2008. doi:10.1177/1524839908323521. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Central Massachusetts Area Health Education Center: Outreach Worker Training Institute. <http://cmahec.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=46&Itemid=59>. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Ward MD, Rieve JA. The role of case management in disease management. In: Todd WE, Nash E, eds. Disease management: A Systems Approach to Improving Patient Outcomes. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 1997:235–59.

Laiteerapong N, Sherman BJ, Kim K, Freund K. Validation of racial categorization in a hospital administrative database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(Suppl 1):130.

Health Connector Facts and Figures, March 2009. Commonwealth Connector. <http://www.mahealthconnector.org/portal/site/connector/menuitem.d7b34e88a23468a2dbef6f47d7468a0c?fiShown=default>. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program Fact Sheet 2004/2005. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):99–119.

David MM, Ko L, Prudent N, Green EH, Posner MA, Freund KM. Mammography use. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(2):253–61.

Palmer RC, Fernandez ME, Tortolero-Luna G, Gonzales A, Mullen DP. Acculturation and mammography screening among Hispanic women living in farmworker communities. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):21–7.

Zambrana RE, Breen N, Fox SA, Gutierrez-Mohamed ML. Use of cancer screening practices by Hispanic women: analyses by subgroup. Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):466–77.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. Physician Practice Connections–Patient-Centered Medical Home (PPC-PCMH). <http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/631/Default.aspx>. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Fisher ES. Building a medical neighborhood for the medical home. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1202–5.

Understanding the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 2010. <http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/medical_home/. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home Released by Organizations Representing More Than 300,000 Physicians. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 2007. <http://www.acponline.org/pressroom/pcmh.htm. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–26

Qaseem A, Snow V, Sherif K, Aronson M, Weiss KB, Owens DK. Screening mammography for women 40 to 49 years of age: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):511–5.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Responds to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s Breast Cancer Guidelines. <http://www.acog.org/acog_districts/dist_notice.cfm?recno=13&bulletin=3160. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Steinbrook R. Health Care and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1057–1060.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Regulations and Guidance. <http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_gov_regulations_and_%20guidance/1496>. Accessed September 13, 2010.

Acknowledgements

Funded by the Avon Foundation Safety Net Grant. The study would like to acknowledge the contributions of Faber Alvis, Mariuca Tuxbury, and Arlene Ash, PhD. This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 32nd annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine conference in Miami in May 2009.

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 30 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, C.E., Rothstein, J.D., Beaver, K. et al. Patient Navigation to Increase Mammography Screening Among Inner City Women. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 123–129 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1527-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1527-2