ABSTRACT

National health reform is expected to increase how long individuals have to wait between requests for appointments and when their appointment is scheduled. The increase in demand for care due to more widespread insurance will result in longer waits if there is not also a concomitant increase in supply of healthcare services. Long waits for healthcare are hypothesized to compromise health because less frequent outpatient visits result in delays in diagnosis and treatment. Research testing this hypothesis is scarce due to a paucity of data on how long individuals wait for healthcare in the United States. The main exception is the Veterans Health Administration (VA) that has been routinely collecting data on how long veterans wait for outpatient care for over a decade. This narrative review summarizes the results of studies using VA wait time data to answer two main questions: 1) How much do longer wait times decrease healthcare utilization and 2) Do longer wait times cause poorer health outcomes? Longer VA wait times lead to small, yet statistically significant decreases in utilization and are related to poorer health in elderly and vulnerable veteran populations. Both long-term outcomes (e.g. mortality, preventable hospitalizations) and intermediate outcomes such as hemoglobin A1C levels are worse for veterans who seek care at facilities with longer waits compared to veterans who visit facilities with shorter waits. Further research is needed on the mechanisms connecting longer wait times and poorer outcomes including identifying patient sub-populations whose risks are most sensitive to delayed access to care. If wait times increase for the general patient population with the implementation of national reform as expected, U.S. healthcare policymakers and clinicians will need to consider policies and interventions that minimize potential harms for all patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington D.C: Institute of Medicine; 2001.

Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare, J Gen Intern Med. In press. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1806-6

Buchmueller TC, Grumbach K, Kronick R, Kahn JG. The rffect of health insurance on medical care utilization and implications for insurance expansion: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(1):3–30.

Congressional Budget Office. Key issues in analyzing major health insurance proposals. Washington D.C.; 2008. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/99xx/doc9924/toc.shtml [Accessed on October 13, 2010].

Kowalczyk L. Across Mass., waits to see the doctor grows. The Boston Globe. September 22, 2008.

Fogarty C, Cronin P. Waiting for healthcare: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2007;61(4):463–471.

Eilers GM. Improving patient satisfaction and waiting time. J Am Coll Heal. 2004;53(1):41–45.

Kenagy JW, Berwick DM, Shore MF. Service quality in health care. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281(7):661–665.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):S4–S36.

Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Sanders LJ, Jannisse D, Pogach LM. Preventive foot care in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(12):2161–2177.

The doctor will see you in 3 months. Bloomberg Businessweek, 2007.

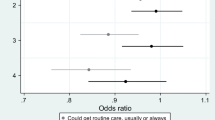

Prentice JC, Pizer SD. Delayed access to health care and mortality. Heal Serv Res. 2007;42(2):644–662.

Prentice JC, Pizer SD. Waiting times and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Outcomes ResMethodology. 2008;8:1–18.

Prentice JC, Fincke BG, Miller DR, Pizer SD. Waiting for primary care and health outcomes among elderly patients with diabetes. Health Serv Res. In Press.

Prentice JC, Fincke BG, Miller DR, Pizer SD. Outpatient waiting times and diabetes care quality improvement. Am J Managed Care. 2011;17(2):e43–e54.

United States General Accounting Office. VA needs better data on extent and causes of waiting times; 2000. GAO/HEHS-00-90.

United States General Accounting Office. More national action needed to reduce waiting times, but some clinics have made progress. 2001:22 GAO-01-953.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Priority for outpatient medical services and inpatient hospital care: 2002. VHA Directive 2002–059.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Process for managing patients when patient demand exceeds current clinical capacity: VHA Directive 2003.2003-068.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Process for ensuring timely access to outpatient clinical care: 2006. VHA Directive 2006–028.

Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA outpatient scheduling processes and procedures 2010. 2010. VHA Directive 2010–027.

Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:1035–1040.

Yang Z, Gilleskie DB, Nortaon EC. Prescription drugs, medical care and health outcomes: a model of elderly health dynamics: University of North Carolina; 2006.

AHRQ wuality indicators-Guide to prevention wuality indicators: hospital sdmission for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. 02-R0203.

Wang G, Zhang Z, Ayala C, Wall HK, Fang J. Cost of heart failure-related hospitalizations in patients aged 18 to 64 years. Am J Managed Care. 2010;16(10):769–776.

Pizer SD, Prentice JC. Time Is money: delayed access to outpatient care and health insurance choices of elderly veterans in the United States. J Health Econ. In press.

Baar B. New patient monitor: data definitions: Veteran Health Administration Support Services Center; 2005.

Ross SA. Controlling diabetes: the need for intensive therapy and barriers in clinical management. Diabetes Res Clin Practice. 2004;65S:S29–S34.

Helmer DA, Sambamoorthi U, Rajan M, Tseng C-L, Pogach LM. Glycemic control in elderly veterans with diabetes: individualized, not age-based. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:728–731.

Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Sperl-Hillen JM, et al. Does improved access to care affect utilization and costs for patients with chronic conditions? Am J Managed Care. 2004;10(10):717–722.

Subramanian U, Ackermann RT, Brizendine EJ, et al. Effect of advanced access scheduling on processes and intermediate outcomes of diabetes care and utilization. J Gen Internal Med. 2009;24(3):327–333.

Knight K, Badamgarav E, Henning JM, et al. A systematic review of diabetes disease management programs. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11:242–250.

Norris SL, JNichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, 4S, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:15–38.

Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for Type 2 Diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:427–440.

Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Archives of Internal Med. 1990;150:1509–1510.

Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119:3028–3035.

Gravelle H, Siciliani L. Third degrees waiting time discrimination: optimal allocation of a public sector healthcare treatment under rationing by waiting. Heal Econ. 2009;18:977–986.

Alter DA, Newman AM, Cohen EA, Sykora K, Tu JV. The evaluation of a formalized queue management system for coronary angiography waiting lists. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21(13):1203–1209.

Sabik LM, Lie RK. Priority setting in health care: lessons from the experiences of eight countries. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7(4):1–13.

Willcox S, Seddon M, Dunn S, Edwards RT, Pearse J, Tu JV. Measuring and reducing waiting times: A cross-national comparison of strategies. Heal Aff. 2007;26(4):1078–1087.

Congressional Budget Office CB. Quality initiatives undertaken by the Veterans Health Administration; 2009. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/104xx/doc10453/08-13-VHA.pdf [Accessed on October 21, 2010]

Lukas CV, Meterko M, Mohr D, Seibert MN. The implementation and effectiveness of advanced clinicaccess. HSR&D Management Decision and Research Center. Boston: Office of Research and Development, Department of Veteran Affairs; 2004:80.

Congressional Budget Office. The potential cost of meeting demand for veterans’ health care. 2005. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/61xx/doc6171/03-23-Veterans.pdf [Accessed on September 28, 2010].

Young BA, Lin E, Korff MV, Simon G, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Everson-Stewart S, Kinder L, Oliver M, Boyko EJ, Katon WJ. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Managed Care. 2008;14(1):15–24.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

Funding Sources and Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by Grant No: IAD-06-112 and IIR 04–233 from the Health Services Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs and Grant No: 62967 from the Health Care Financing and Organization Initiative under the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Neither author has any conflicts of interest to report. The authors are indebted to Matthew Neuman and John Gardner for programming support. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. This research was approved by the VA Boston Health Care System institutional review board.

Conflict of interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pizer, S.D., Prentice, J.C. What Are the Consequences of Waiting for Health Care in the Veteran Population?. J GEN INTERN MED 26 (Suppl 2), 676 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1819-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1819-1