Abtract

BACKGROUND

Incarceration is associated with poor health and high costs. Given the dramatic growth in the criminal justice system’s population and associated expenses, inclusion of questions related to incarceration in national health data sets could provide essential data to researchers, clinicians and policy-makers.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate a representative sample of publically available national health data sets for their ability to be used to study the health of currently or formerly incarcerated persons and to identify opportunities to improve criminal justice questions in health data sets.

DESIGN & APPROACH

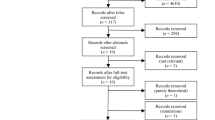

We reviewed the 36 data sets from the Society of General Internal Medicine Dataset Compendium related to individual health. Through content analysis using incarceration-related keywords, we identified data sets that could be used to study currently or formerly incarcerated persons, and we identified opportunities to improve the availability of relevant data.

KEY RESULTS

While 12 (33%) data sets returned keyword matches, none could be used to study incarcerated persons. Three (8%) could be used to study the health of formerly incarcerated individuals, but only one data set included multiple questions such as length of incarceration and age at incarceration. Missed opportunities included: (1) data sets that included current prisoners but did not record their status (10, 28%); (2) data sets that asked questions related to incarceration but did not specifically record a subject’s status as formerly incarcerated (8, 22%); and (3) longitudinal studies that dropped and/or failed to record persons who became incarcerated during the study (8, 22%).

CONCLUSIONS

Few health data sets can be used to evaluate the association between incarceration and health. Three types of changes to existing national health data sets could substantially expand the available data, including: recording incarceration status for study participants who are incarcerated; recording subjects’ history of incarceration when this data is already being collected; and expanding incarceration-related questions in studies that already record incarceration history.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the US Population, 1974–2001. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 2003.

Glaze LE. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2009. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 2010.

Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–35.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. Department of Justice: Washington DC. 2004.

Solomon A, Osborne J, LoBuglio S, Mellow J, and Mukamal D. Life After Lockup: Improving reentry from jail to the community. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. 2008.

Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–72.

Pew Center on the States. One in 100: Behind bars in America 2008. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts. February 2008.

Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–65.

Hammett TM, Roberts C, Kennedy S. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime & Delinquency. 2001;47(3):390–409.

Mallik-Kane K and Visher CA. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Research Report. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. February 2008.

National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Behind bars: Substance abuse and America's prison population. New York, NY: CASA Columbia. 1998.

The Urban Institute. Public health dimensions of prisoner reentry: Addressing the health needs and risks of returning prisoners and their families. Meeting Summary. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. December 2002.

Mumola C. Special report: substance abuse and treatment state and federal prisoners, 1997. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 1999.

Glaser JB, Greifinger RB. Correctional health care: a public health opportunity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(2):139–45.

National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: NCCHC. 2002.

Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912–9.

Aday R. Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2003.

Anno B, Graham C, Lawrence J, Shansky R. Correctional Health Care: Addressing the Needs of Elderly, Chronically Ill, and Terminally Ill Inmates. Middletown, CT: Criminal Justice Institute; 2004.

Baillargeon J, Black SA, Pulvino J, Dunn K. The disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):74–80.

Mitka M. Aging prisoners stressing health care system. JAMA. 2004;292(4):423–4.

Gorman B. With soaring prison costs, states turn to early release of aged, infirm inmates. Washington DC: National Conference of State Legislatures; 2008.

Farrell M, Marsden J. Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction. 2008;103(2):251–5.

Stewart LM, Henderson CJ, Hobbs MS, Ridout SC, Knuiman MW. Risk of death in prisoners after release from jail. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(1):32–6.

Verger P, Rotily M, Prudhomme J, Bird S. High mortality rates among inmates during the year following their discharge from a French prison. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(3):614–6.

Travis J, Solomon AL, Waul M. From Prison to Home: The Dimensions and Consequences of Prisoner Reentry. Washington: Urban Institute; 2001.

Hammett TM, Gaiter JL, Crawford C. Reaching seriously at-risk populations: health interventions in criminal justice settings. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(1):99–120.

Public Health Behind Bars: From Prisons to Communities, ed. Robert Greifinger. New York: Springer. 2007,576 pgs.

Wang EA, Pletcher M, Lin F, et al. Incarceration, incident hypertension, and access to health care: findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):687–93.

Colsher PL, Wallace RB, Loeffelholz PL, Sales M. Health status of older male prisoners: a comprehensive survey. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):881–4.

Maruschak L. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Medical Problems of Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2006.

Smith AK, Ayanian JZ, Covinsky KE, et al. Conducting High-Value Secondary Dataset Analysis: An Introductory Guide and Resources. J Gen Intern Med. 2011.

Gostin LO. Biomedical research involving prisoners: ethical values and legal regulation. JAMA. 2007;297(7):737–40.

Wang EA, Wildeman C. Studying health disparities by including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1708–9.

Chiu T. It's About Time: Aging prisoners, increasing costs, and geriatric release. New York, NY: The Vera Institute of Justice; 2010.

Maul F. Delivery of end-of-life care in the prison setting. In: Puisis M, ed. Clinical practice in correctional medicine. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA; 2006:529–37.

Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–76.

Massoglia M. Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law & Society Review. 2008;42(2):275–306.

Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(2):115–30.

US Dept. of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2004. ICPSR04572-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2007

Author Contributions

Study Concept and Design: Ahalt, Williams

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: Ahalt, Binswanger, Steinman and Williams

Preparation of Manuscript, Critical Review: Ahalt, Binswanger, Steinman, Tulsky and Williams

No other parties contributed substantially to this research or to preparation of this manuscript.

Funders

Dr. Williams is supported by the National Institute of Aging (K23AG033102), the UCSF Hartford Center of Excellence, and the Langeloth Foundation. Dr. Binswanger is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program. These funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Mr. Ahalt, Dr. Williams, and Dr. Steinman are employees of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The opinions expressed in this manuscript may not represent those of the VA.

Prior Presentations

The abstract for this paper has been presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, May 5, 2011.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Williams has been a consultant about prison conditions of confinement. Dr. Steinman helped to create the SGIM Dataset Compendium. These relationships did not affect the analysis of the data or preparation of this manuscript. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, or affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahalt, C., Binswanger, I.A., Steinman, M. et al. Confined to Ignorance: The Absence of Prisoner Information from Nationally Representative Health Data Sets. J GEN INTERN MED 27, 160–166 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1858-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1858-7