Abstract

Introduction

The NCI developed the print-based educational brochure, Facing Forward, to fill a gap in helping cancer patients meet the challenges of transitioning from active treatment to survivorship; however, little research has been conducted on its efficacy.

Purpose

The aims of this study were to evaluate the efficacy of Facing Forward in promoting the uptake of recommended behaviors (e.g., ways to manage physical changes) and to explore its usability.

Methods

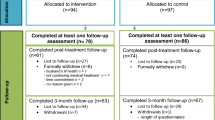

At the last treatment appointment, early-stage breast, prostate, colorectal, and thoracic cancer patients (N = 340) recruited from community clinical oncology practices and an academic medical center completed a baseline assessment and were randomized to receive either Facing Forward (n = 175) or an attention control booklet about the NCI’s Cancer Information Service (n = 165). Patients completed follow-up assessments at 8 weeks and 6 months post-baseline.

Results

The reported uptake of recommended stress management behaviors was greater among intervention than control participants at both 8 weeks post-baseline (p = 0.016) and 6 months post-baseline (p = 0.017). At 8 weeks post-baseline, the intervention control group difference was greater among African-American than Caucasian participants (p < 0.03) and significant only among the former (p < 0.003); attendance at a cancer support group was also greater among the intervention than control group participants (p < 0.02). There were no significant intervention control group differences in the reported uptake of recommended behaviors in three other categories (p > 0.025). Intervention participants rated Facing Forward as understandable and helpful and indicated a high level of intention to try the behaviors recommended.

Conclusions

Facing Forward can enhance early-stage survivors’ reported ability to manage stress and increase support group use during the reentry period.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Facing Forward can help survivors meet the challenges of the reentry period.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel R, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):212–36.

Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):1996–2005.

ACS. Cancer treatment and survivorship: facts & figures 2012–2013; 2012. Atlanta.

Society AC. Cancer facts and figures 2012; 2012.

Miller SM, Bowen DJ, Croyle RT, Rowland J, editors. Handbook of cancer control and behavioral science: a resource for researchers, practitioners, and policy makers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Mullan, F. Re-entry: the educational needs of the cancer survivor. Health Education Quarterly 1984; 10 (Supplement):88–94.

Mullan F. Occasional notes: seasons of survival: reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–3.

Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008.

Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5132–7.

Stanton AL. What happens now? Psychosocial care for cancer survivors after medical treatment completion. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1215–20.

Hewitt M, Sheldon Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Committee on Cancer Survivorship: improving care and quality of life. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; 2006.

Green BL, et al. Trauma history as a predictor of psychologic symptoms in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(5):1084–93.

Henselmans l. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):160–8.

Kantsiper M, et al. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 Suppl 2:S459–66.

Allen JD, Savadatti S, Levy AG. The transition from breast cancer 'patient' to 'survivor'. Psychooncology. 2009;18(1):71–8.

Henselmans I, et al. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):160–8.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. p. 536.

Bacon CG, et al. The association of treatment-related symptoms with quality-of-life outcomes for localized prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;94(3):862–71.

Jim HS, Jacobsen PB. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in cancer survivorship: a review. Cancer J. 2008;14(6):414–9.

Benard VB, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2910–8.

Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 3:49–55.

McKinley ED. Under Toad days: surviving the uncertainty of cancer recurrence. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(6):479–80.

Biesecker A. Side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy: perceptions of node-negative breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 1997;6(2):85–93.

Beisecker A, et al. Side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy: perceptions of node-negative breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 1997;6(2):85–93.

Armes J, et al. Patients' supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6172–9.

Harrison JD, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(8):1117–28.

N.E. Adler, A.E.K Page, editors. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs; 2008, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Miller SM. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease. Implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76(2):167–77.

Miller SM, Shoda Y, Hurley K. Applying cognitive-social theory to health-protective behavior: breast self-examination in cancer screening. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(1):70–94.

Casillas J, Ganz PA. Physical late effects of cancer. In: Miller SM et al., editors. Handbook of cancer control and behavioral science. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. p. 431–48.

Squiers L, et al. Cancer patients' information needs across the cancer care continuum: evidence from the cancer information service. J Health Commun. 2005;10 Suppl 1:15–34.

Ganz PA, et al. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1101–9.

Stanton AL, et al. Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2608–13.

Institute of Medicine. Facing forward: life after cancer treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

NCI’s Cancer Information Service (CIS) (2010) What is the NCI's cancer information service?

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P. Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(5):437–43.

Shaffer JP. Multiple hypothesis testing. Annual Review of Psychology, 1995;46:561–84.

Holland JC, Alici Y. Management of distress in cancer patients. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(1):4–12.

Gottlieb BH, Wachala ED. Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):379–400.

Hoey LM, et al. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):315–37.

Miller SM, Bowen D J, Croyle RT, Rowland, J, (ed). Handbook of cancer control and behavioral science: a resource for researchers, practitioners, and policy makers, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Smith KB, Pukall CF. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):465–75.

Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database System Review. 2007;3:1–99.

Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for fatigued cancer survivors: long-term follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(5):612–8.

Miller SM, Bowen DJ, Cfroyle RT, Rowland JH, editors. Cancer control and behavioral science: a resource for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008.

Fogel J, Ribisl KM, Morgan PD, Humphreys K, Lyons EJ. Underrepresentation of African Americans in online cancer support groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):705–12.

Squiers L, Rutten LF, Teiman MA, Hesse B. Cancer patients' information needs across the cancer care continuum: evidence from the Cancer Information Service. J Heal Commun. 2005;10:15–34.

Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Hesse B. Cancer-related information seeking: hints from the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Commun. 2006;11 Suppl 1:147–56.

Thompson VLS, Cacazos-Rehg P, Tate KY, Gaier A. Cancer information seeking among African Americans, Journal of Cancer Education. 2008;23:92–101.

Garofalo JP, et al. Uncertainty during transition from cancer patient to survivor. Cancer Nursing. 2009;32(4):E8–E14.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health grants R01 CA104979, 5P01 CA057586, and the Fox Chase Cancer Center Behavioral Research Core Facility P30 CA06927, as well as Department of Defense grants DAMD 17-01-01-1-0238 and DAMD 17-02-1-0382 and the LAF PT07-07020 grant. We are indebted to Mary Anne Ryan for her technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buzaglo, J.S., Miller, S.M., Kendall, J. et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and usability of NCI’s Facing Forward booklet in the cancer community setting. J Cancer Surviv 7, 63–73 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0245-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0245-7