Abstract

Photodynamic therapy uses nonthermal coherent light delivered via fiber optic cable to locally activate a photosensitive chemotherapeutic agent that ablates tumor tissue. Owing to the limitations of light penetration, it is unknown whether photodynamic therapy can treat large osseous tumors. We determined whether photodynamic therapy can induce necrosis in large osseous tumors, and if so, to quantify the volume of treated tissue. In a pilot study we treated seven dogs with spontaneous osteosarcomas of the distal radius. Tumors were imaged with MRI before and 48 hours after treatment, and the volumes of hypointense regions were compared. The treated limbs were amputated immediately after imaging at 48 hours and sectioned corresponding to the MR axial images. We identified tumor necrosis histologically; the regions of necrosis corresponded anatomically to hypointense tissue on MRI. The mean volume of necrotic tissue seen on MRI after photodynamic therapy was 21,305 mm3 compared with a pretreatment volume of 6108 mm3. These pilot data suggest photodynamic therapy penetrates relatively large canine osseous tumors and may be a useful adjunct for treatment of bone tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses a nonthermal laser delivered light through a fiber optic cable to stimulate a photoactivated chemotherapeutic agent (photosensitizer) that ablates tumor cells [10, 16, 17, 23, 26, 30, 33, 36]. PDT has limited systemic and local side effects [3, 32, 33]. Previous rodent studies suggest PDT can ablate various forms of bone cancer [4, 5, 31, 37], although our concern has been whether PDT can induce necrosis in larger osseous tumors given presumed limitations of light penetration in osseous tumors.

The purpose of this study was to determine if PDT could induce necrosis in large osseous tumors and to quantify the volume of tumor tissue ablated.

Materials and Methods

For this pilot study, we identified seven large-breed pet dogs (33–65.5 kg) with spontaneous osteosarcomas in the forelimb distal radius through the oncology clinic at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine. The radiographs and MR images of all the animals tested were consistent with osteosarcoma and later confirmed by histology. All tumors were classified as Stage IIb [12, 13] and all of the tumors in the dogs except one had areas of spontaneous necrosis present before therapy identified on MRI (T1 gadolinium sequences). Consent for treatment was obtained from the owners of the dogs. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine.

The dogs were anesthetized and premedicated intravenously using oxymorphone (0.05 mg/kg) and atropine (0.2 mg/kg). Ketamine (5 mg/kg) and diazepam (0.25 mg/kg) were used for induction. Anesthesia following endotracheal intubation was maintained with isofluorane and oxygen. A pretreatment MRI (T1, T2, and T1 gadolinium) of the affected limb was performed and the dogs then were taken to the surgical suite where PDT was performed (Fig. 1).

The affected limb was prepared and draped in sterile fashion. A 2-mm stainless steel guide rod was placed through a small stab incision over the proximal anterior surface of the affected radius and advanced through the intramedullary canal of the radius into the osteosarcoma under fluoroscopic guidance. A cannulated trochar was placed over the guide rod and advanced to the center of the tumor. The guide rod then was removed and a 0.94-mm fiber optic cable was advanced through the guide rod and placed in the tumor. The location of the cannulated trochar and placement of the treatment fiber in the tumor were confirmed by intraoperative fluoroscopy. The photosensitizer verteporfin (benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid; QLT, Inc, Vancouver, Canada) then was administered systemically (0.4 mg/kg) through an intravenous access portal over 10 minutes before light delivery. Light from a 690-nm diode laser was administered 5 minutes after completion of the transfusion of the photosensitizer. Light was delivered at 250 mW/cm over 1000 seconds through a 0.94-mm × 5-cm cylindrical diffuser (Medlight SA, Ecublens, Switzerland) for a total light dose of 500 J/cm. One animal was used as a control in which light was administered at 500 J/cm without administration of the photosensitizer (sham treatment). The fiber optic cable was removed after treatment. The animals were extubated and monitored in the intensive care unit for 48 hours where analgesia was maintained. Forty-eight hours posttreatment, the animals returned to the MRI suite anesthetized and the PDT-treated limbs were reimaged using the pretreatment MRI protocol. Immediately after imaging, the animals were taken to the procedure room and the affected forelimbs were amputated with wide margins, in conventional fashion. The dogs were followed clinically in the oncology unit postoperatively and received routine neoadjuvant cisplatinum.

The forelimb of the dog was amputated and sectioned from the wrist. Seventeen sections were cut in the axial plane to correlate with alternate axial MR images based on the distance from the distal radius. The specimens then were decalcified in 10% formic acid over 28 days and sectioned using a microtome. The sections from each amputated limb were fixed on microscopy slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and analyzed under light microscopy by one of the authors (SB) and a dedicated musculoskeletal pathologist (RK). Anatomic features of the histology sections were used to confirm the correlation between MRI and histology sections. The tissue around the fiber optic cable tract was assessed microscopically.

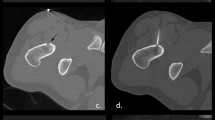

The area in the tumor with hypointense signal on before and after PDT axial MRI sequences (T1 with gadolinium) was measured and compared. The hypointense regions signified avascular tissue [7, 19, 21]. The MR images of each animal were reviewed independently by a musculoskeletal radiologist (CC). We measured the anteroposterior, mediolateral, and rostrocaudal extent of hypointense tissue in the tumor using a calibrated ruler in Merge eFilm™ (Milwaukee, WI) DICOM software. We then computed the volume of the tumor tissue with hypointense signal using Mimics™ software (Materialise, Inc, Leuven, Belgium) (Fig. 2). The volumetric assessment was calculated for each treatment site by interpolating in the rostrocaudal plane the area of hypointense signal on the axial MRI through the software’s algorithm. We believed this to be a more accurate representation of the effect of PDT versus data given just for one representative region. The mean volumes of tissue with hypointense signal were compared before and posttreatment using a paired Student’s t test.

(A) A preoperative sagittal T1 gadolinium MR image for Dog MQ shows the location of the osteosarcoma affecting the radius. (B) In a postoperative T1 gadolinium MR image, the hypointense signal (circle) is seen 48 hours after PDT. (C) A pretreatment axial section shows the size and location of the osteosarcoma compared with (D) a posttreatment axial T1 gadolinium MR image. The dimensions of the hypointense signal before and post-PDT were measured and compared.

Finally, the pattern and distribution of hypointense signal seen on the axial MRI were compared with the corresponding axial histology sections to assess whether the pattern and distribution of hypointense tissue posttreatment correlated with necrosis on histology. This was performed by comparing anatomic features of the histology sections to anatomic features of the MRI slices taken equidistant from the wrist.

Results

PDT induced necrosis in all osteosarcomas treated (Table 1; Fig. 3). The area of necrosis was easily seen on gross sectioning. The tract of the fiber optic cable was identified and the treated tumor and peripheral tissue were examined in reference to this landmark. The hematoxylin and eosin sections showed areas of extensive hemorrhagic necrosis and cellular necrosis throughout the tumor around the fiber tract. Regions of necrosis were characterized by areas without cells with blood pooling and by regions with necrotic cells, qualitatively characterized by loss of cellular volume, hyperpigmentation, and increased nuclear density. The latter was found toward the periphery of the treatment site compared with the former found closer to the fiber tract (Fig. 3). Bone necrosis, as seen by empty osteocyte lacunae, also was evident in three of the dogs after PDT. However, no structural damage to bone outside the fiber tract was identified. In the control animal, blood pooling occurred along the fiber tract but was confined to the tract. The tumor in the control dog had viable tumor cells without evidence of necrosis adjacent to the fiber tract in contrast to the treated tumors.

(A) A ×10 magnification photomicrograph and (B) a ×20 magnification photomicrograph of sections of treated canine osteosarcoma show necrosis (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin). (C) Blood pooling after treatment was identified in sections in all animals treated except for the control animal (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×20). (D) A photomicrograph shows untreated tumor tissue (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×20). (E) An axial T1 gadolinium MR image shows the area of hypointense tissue seen after treatment. The regions from which the histologic specimen were obtained that are shown in Illustrations A, B, and C are noted by the arrows. (F) A preoperative axial section of the same level shows the original size and location of the osteosarcoma affecting the radius.

The mean volume of necrotic tissue seen on MRI after PDT (21,305 mm3) was larger (p < 0.003) than the mean pretreatment volume (6108 mm3) (Table 1). The mean anterior to posterior dimensions of the hypointense tissue after PDT was 2.5 cm (range, 2.2–2.8 cm), the mean medial to lateral dimension was 2.6 cm (range, 1.7–2.8 cm), and the mean rostral to caudal dimension was 5.3 cm (range, 4–9.2 cm) (Table 1). The hypointense tissue surrounding the treatment fiber tract seen on posttreatment MRI was increased (p < 0.003) compared with pretreatment MRI except for the control (Fig. 4).

A graph shows the effect of PDT on canine osteosarcomas. The seven dogs with spontaneous forelimb osteosarcomas were treated with PDT; one dog acted as a control (light only). Volumes of necrosis seen on T1 gadolinium sequences were measured and compared with the corresponding preoperative images. The mean posttreatment volume was larger (p < 0.003) than the pretreatment volume.

The distribution of hypointense signal seen on T1 gadolinium sequences matched the pattern and distribution of necrosis seen on the corresponding histology sections (Figs. 2, 3). Likewise, the axial dimension of hypointense tissue on the control’s posttreatment MRI was minimal and determined to be 3 mm, corresponding to the passage of the cannula.

Discussion

PDT uses nonthermal coherent light delivered via fiber optic cable to locally activate a photosensitive chemotherapeutic agent that ablates tumor tissue. It is unknown whether PDT can treat large osseous tumors owing to the limitations of light penetration. In this pilot study, we determined if PDT can induce necrosis in large osseous tumors and quantified the volume of treated tissue in seven dogs with spontaneous osteosarcomas of the distal radius.

Osteosarcomas are common in dogs and commonly affect the radius. The characteristics of canine osteosarcomas are histologically similar to those of human osteosarcomas and we therefore presumed this was a good model to test our hypothesis. Limits to this study include the limited number of dogs that were treated and the limited number of control animals. However, this was a pilot study, and owing to ethical reasons, a limited number of animals were used with limited followup (48 hours) before amputation. The long-term clinical followup of the dogs was not reported because the dogs were lost to followup (<1 year), making it difficult to determine whether the treatment had either a positive or negative effect on the dog’s survival. Likewise, a potential downside of the technique used is potential seeding of tumor tissue into adjacent tissue during placement and withdrawal of the fiber optic cable and hemorrhage secondary to fiber placement. Our assessments were not blinded, although we did not believe this essential for this pilot study. Finally, our study was limited in that there was variability in lesion sizes produced in animals with the same type of tumor. This can be explained in part by the following: the osteosarcomas in this study were all Stage IIb and some dogs had areas of spontaneous necrosis noted preoperatively. Placement of fibers in an area of preexisting necrosis served to limit the measurable effect attributed to PDT and skewed the results negatively. For example, the cylindrical diffusing tip was placed in an area of preexisting necrosis in the tumor of one animal (Dog JR, Table 1). The measurable lesion in this animal’s osteosarcoma was limited on the post-PDT MRI because the preexisting necrosis was indiscernible in the mediolateral plane from the lesion created from the PDT, rather than because there was a poor response to treatment in that tumor. In contrast, in animals in which there was no or limited spontaneous necrosis preoperatively, large areas of necrosis from PDT treatment were determined easily.

We observed necrosis histologically and on MRI. Although necrosis was seen in all tumors except one before PDT, the extent of necrosis after PDT was substantial in all of the PDT-treated radii except for the control. The hypointense tissue on MRI matched the area of necrosis seen on histologic specimen, and we were able to obtain a volumetric measurement from the MRI to determine the volume of necrosis after PDT was substantially increased.

The effect of PDT is mediated through direct ablation and immune-mediated vascular stasis [11, 16]. We found a mean treatment effect size of approximately 16 cm3, with a consistent effect seen in the anteroposterior (2.5 cm) and mediolateral (2.6 cm) dimensions. The effect measured along the rostrocaudal (5.2 cm) plane correlated well with the length of the diffusing tip used for treatment in this study (5 cm).

Our results are consistent with those of several trials in rodents largely consisting of experiments in orthotopic osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma models [8, 14, 20, 28, 31]. In these studies, PDT was able to ablate primary bone tumors, although the size of the tumors was small. Several other animal studies showed PDT can induce necrosis in metastatic adenocarcinomas in bone as well [4, 6]. Burch et al. [4] showed, with a bioluminescent metastatic rat model, PDT ablated human breast cancer in the axial and appendicular skeleton. Several other early-phase clinical trials have shown PDT is capable of ablating various primary human cancers, including breast, prostate, bladder, and lung cancer [2, 9, 10, 15, 17, 18, 24, 27, 29, 38]. However, the extent of ablation was limited in most of these studies because the light source had to be placed on the surface of the diseased tissue and not directly in the tumor. In contrast, the fiber can be placed in the center of the tumor in osseous tumors. It may be the skeleton is the ideal place for PDT since the fiber optic cable can be placed directly in the bone without compromising the native tissue.

Our data show PDT can induce tumor necrosis in relatively large bone tumors and the light penetration does not appear to be a limiting factor in the animals treated. The treatment protocol in our study used one 0.94-mm fiber. However, the treatment effect could be increased by using multiple fibers placed accordingly. Arguably, complete ablation of the osteosarcoma in a dog may have been obtained if several fibers were appropriately arranged in the tumor in the medullary canal. The technique also is applicable to the axial skeleton, and Burch et al. [5] also examined safe application of low-dose PDT in porcine vertebrae and canine vertebrae. The average volume of necrosis in dogs in the current study is approximately the size of large metastatic lesions seen in the thoracic and lumbar spine [1, 11]. PDT may have potential as an adjunctive therapy for treatment of spinal metastases along with radiation and bisphosphonates [22, 25, 34, 35, 39].

Our pilot data suggest PDT can ablate a considerable volume of large bone tumors and the light penetration in osseous tumors is not a limiting factor. The other benefits of PDT are that it is minimally invasive (the treatment fiber is less than 1 mm in diameter); because it is targeted, it has limited systemic and local side effects and repeat treatments can be made; the treatment time is, on average, extremely short (33 minutes); and it could easily be used as an adjunct with other strategies to treat osseous tumors.

References

Aebi M. Spinal metastasis in the elderly. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(suppl 2):S202–S213.

Barnett AA, Haller JC, Cairnduff F, Lane G, Brown SB, Roberts DJ. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolaevulinic acid for the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:829–832.

Brown SB, Brown EA, Walker I. The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497–508.

Burch S, Bisland SK, Bogaards A, Yee AJ, Whyne CM, Finkelstein JA, Wilson BC. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of vertebral metastases in a rat model of human breast carcinoma. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:995–1003.

Burch S, Bisland SK, Wilson BC, Whyne C, Yee AJ. Multimodality imaging for vertebral metastases in a rat osteolytic model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;454:230-236.

Burch S, Bogaards A, Siewerdsen J, Moseley D, Yee A, Finkelstein J, Weersink R, Wilson BC, Bisland SK. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of metastatic lesions in bone: studies in rat and porcine models. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:034011.

Casas A, Di Venosa G, Batlle A, Fukuda H. In vitro photosensitisation of a murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell line with Verteporfin. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002;48:931–937.

Cincotta L, Szeto D, Lampros E, Hasan T, Cincotta AH. Benzophenothiazine and benzoporphyrin derivative combination phototherapy effectively eradicates large murine sarcomas. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;63:229–237.

Cortese DA, Edell ES, Kinsey JH. Photodynamic therapy for early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:595–602.

Cuenca RE, Allison RR, Sibata C, Downie GH. Breast cancer with chest wall progression: treatment with photodynamic therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:322–327.

Drury AB, Palmer PH, Highman WJ. Carcinomatous metastasis to the vertebral bodies. J Clin Pathol. 1964;17:448–457.

Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Instr Course Lect. 1988;37:3–10.

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;153:106–120.

Fingar VH, Kik PK, Haydon PS, Cerrito PB, Tseng M, Abang E, Wieman TJ. Analysis of acute vascular damage after photodynamic therapy using benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD). Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1702–1708.

Friedberg JS, Mick R, Stevenson JP, Zhu T, Busch TM, Shin D, Smith D, Culligan M, Dimofte A, Glatstein E, Hahn SM. Phase II trial of pleural photodynamic therapy and surgery for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with pleural spread. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2192–2201.

Goodell TT, Muller PJ. Photodynamic therapy: a novel treatment for primary brain malignancy. J Neurosci Nurs. 2001;33:296–300.

Hendren SK, Hahn SM, Spitz FR, Bauer TW, Rubin SC, Zhu T, Glatstein E, Fraker DL. Phase II trial of debulking surgery and photodynamic therapy for disseminated intraperitoneal tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:65–71.

Kato H, Furukawa K, Sato M, Okunaka T, Kusunoki Y, Kawahara M, Fukuoka M, Miyazawa T, Yana T, Matsui K, Shiraishi T, Horinouchi H. Phase II clinical study of photodynamic therapy using mono-L-aspartyl chlorine 6 and diode laser for early superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:103–111.

Kawamoto S, Shirai N, Strandberg JD, Boxerman JL, Bluemke DA. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis: MR perfusion imaging evaluation in an experimental model. Acad Radiol. 2000;7:83–93.

Kusuzaki K, Minami G, Takeshita H, Murata H, Hashiguchi S, Nozaki T, Ashihara T, Hirasawa Y. Photodynamic inactivation with acridine orange on a multidrug-resistant mouse osteosarcoma cell line. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:439–445.

Lang P, Wendland MF, Saeed M, Gindele A, Rosenau W, Mathur A, Gooding CA, Genant HK. Osteogenic sarcoma: noninvasive in vivo assessment of tumor necrosis with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Radiology. 1998;206:227–235.

Lipton A. Bisphosphonates and breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80(8 suppl):1668–1673.

Lou PJ, Jones L, Hopper C. Clinical outcomes of photodynamic therapy for head-and-neck cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:311–317.

Lustig RA, Vogl TJ, Fromm D, Cuenca R, Alex Hsi R, D’Cruz AK, Krajina Z, Turic M, Singhal A, Chen JC. A multicenter Phase I safety study of intratumoral photoactivation of talaporfin sodium in patients with refractory solid tumors. Cancer. 2003;98:1767–1771.

Maranzano E, Bellavita R, Floridi P, Celani G, Righetti E, Lupattelli M, Panizza BM, Frattegiani A, Pelliccioli GP, Latini P. Radiation-induced myelopathy in long-term surviving metastatic spinal cord compression patients after hypofractionated radiotherapy: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60:281–288.

Marmur ES, Schmults CD, Goldberg DJ. A review of laser and photodynamic therapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2 Pt 2):264–271.

Momma T, Hamblin MR, Wu HC, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy of orthotopic prostate cancer with benzoporphyrin derivative: local control and distant metastasis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5425–5431.

Nomura J, Yanase S, Matsumura Y, Nagai K, Tagawa T. Efficacy of combined photodynamic and hyperthermic therapy with a new light source in an in vivo osteosarcoma tumor model. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2004;22:3–8.

Pass HI, Temeck BK, Kranda K, Thomas G, Russo A, Smith P, Friauf W, Steinberg SM. Phase III randomized trial of surgery with or without intraoperative photodynamic therapy and postoperative immunochemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:628–633.

Plaks V, Koudinova N, Nevo U, Pinthus JH, Kanety H, Eshhar Z, Ramon J, Scherz A, Neeman M, Salomon Y. Photodynamic therapy of established prostatic adenocarcinoma with TOOKAD: a biphasic apparent diffusion coefficient change as potential early MRI response marker. Neoplasia. 2004;6:224–233.

Pogue BW, O’Hara JA, Demidenko E, Wilmot CM, Goodwin IA, Chen B, Swartz HM, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in the radiation-induced fibrosarcoma-1 tumor causes enhanced radiation sensitivity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1025–1033.

Rousset N, Vonarx V, Eleouet S, Carre J, Bourre L, Lajat Y, Patrice T. Cellular distribution and phototoxicity of benzoporphyrin derivative and Photofrin. Res Exp Med (Berl). 2000;199:341–357.

Shackley DC, Briggs C, Gilhooley A, Whitehurst C, O’Flynn KJ, Betts CD, Moore JV, Clarke NW. Photodynamic therapy for superficial bladder cancer under local anaesthetic. BJU Int. 2002;89:665–670.

van der Sande JJ, Boogerd W, Kroger R, Kappelle AC. Recurrent spinal epidural metastases: a prospective study with a complete follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:623–627.

Walsh GL, Gokaslan ZL, McCutcheon IE, Mineo MT, Yasko AW, Swisher SG, Schrump DS, Nesbitt JC, Putnam JB Jr, Roth JA. Anterior approaches to the thoracic spine in patients with cancer: indications and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1611–1618.

Wiedmann M, Caca K, Berr F, Schiefke I, Tannapfel A, Wittekind C, Mossner J, Hauss J, Witzigmann H. Neoadjuvant photodynamic therapy as a new approach to treating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a phase II pilot study. Cancer. 2003;97:2783–2790.

Winsborrow BG, Grondey H, Savoie H, Fyfe CA, Dolphin D. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of photodynamic therapy-induced hemorrhagic necrosis in the murine M1 tumor model. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;66:847–852.

Wyss P, Schwarz V, Dobler-Girdziunaite D, Hornung R, Walt H, Degen A, Fehr M. Photodynamic therapy of locoregional breast cancer recurrences using a chlorin-type photosensitizer. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:720–724.

Zaidat OO, Ruff RL. Treatment of spinal epidural metastasis improves patient survival and functional state. Neurology. 2002;58:1360–1366.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia Chin, MD, Neuroradiology, University of California, San Francisco, for reviewing the MR images of the animals treated in this study and Rita Kandel, MD, Pathology, Mount Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, for reviewing the histology slides of the animals treated in this study. We also thank QLT, Inc, for providing pharmaceutical support for the project by supplying the photosensitizer verteporfin.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

One or more authors (SB) have received funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and QLT Inc, Vancouver, Canada, to complete this research project.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the animal protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Burch, S., London, C., Seguin, B. et al. Treatment of Canine Osseous Tumors with Photodynamic Therapy: A Pilot Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467, 1028–1034 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0678-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0678-5