Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between consumption of alcoholic beverages and lung cancer risk.

Methods

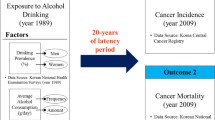

Data were collected in two population-based case–control studies, conducted in Montreal (Study I – mid-1980s and Study II – mid-1990s). Study I included 699 cases and 507 controls, all males; Study II included 1094 cases and 1468 controls, males and females. In each study group (Study I men, Study II men and Study II women) odds ratios (OR) were estimated for the associations between beer, wine or spirits consumption and lung cancer, while carefully adjusting for smoking and other covariates. The reference category included abstainers and occasional drinkers.

Results

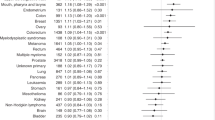

For Study I men, lung cancer risk increased with the average number of beers/week consumed (for 1–6 beers/week: OR=1.2, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.9–1.7; for ≥7 beers/week: OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.1–2.1). For Study II men, beer consumption appeared harmful only among subjects with low fruit and vegetable consumption. In Study II, wine consumers had low lung cancer risk, particularly those reporting 1–6 glasses/week (women: OR=0.3, 95% CI: 0.2–0.4; men: OR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.8).

Conclusions

Beer consumption increased lung cancer risk, particularly so among men who had relatively low fruit and vegetable consumption. Moderate wine drinkers had decreased lung cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reference

Korte JE, Brennan P, Henley SJ, Boffetta P (2002) Dose-specific meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis of the relation between alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 155:496–506

Freudenheim JL, Ritz J, Smith-Warner SA, et al. (2005) Alcohol consumption and risk of lung cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 82:657–667

Bandera EV, Freudenheim JL, Vena JE (2001) Alcohol consumption and lung cancer: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10:813–821

Parkin DM, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Ferlay J, Whelan SL (1998) Histological groups for comparative studies. IARC Technical Report No. 31. IARC, Lyon

Gerin M, Siemiatycki J, Kemper H, Begin D (1985) Obtaining occupational exposure histories in epidemiologic case–control studies. J Occup Med 27:420–426

Siemiatycki J, Wacholder S, Richardson L, Dewar R, Gerin M (1987) Discovering carcinogens in the occupational environment. Methods of data collection and analysis of a large case-referent monitoring system. Scand J Work Environ Health 13:486–492

Leffondre K, Abrahamowicz M, Siemiatycki J, Rachet B (2002) Modeling smoking history: a comparison of different approaches. Am J Epidemiol 156:813–823

Breslow N, Day N (1980) Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume 1: the analysis of case–control studies. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Benedetti A, Abrahamowicz M (2004) Using generalized additive models to reduce residual confounding. Stat Med 23:3781

Hastie T, Tibshirani R (1990) Generalized additive models, Chapman and Hall, London

Parkin DM, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Ferlay J, Whelan SL (1998) Histological groups for comparative studies. IARC Technical Report No. 31. IARC, Lyon

Gilpin E, Pierce J, Cavin S, et al. (1994) Estimates of population smoking prevalence: self vs. proxy reports of smoking status. Am J Public Health 84:1576

Patrick D, Cheadle A, Thompson D, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S (1994) The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 84:1093

Nelson L, Lonstreth WJ, Koepsell T, Checkoway H, van Belle G (1994) Completeness and accuracy of interview data from proxy respondents: demographic, medical, and life-style factors. Epidemiology 5:204

Alberg AJ, Samet JM (2003) Epidemiology of Lung Cancer. Chest 123:21S–49

Riboli E, Norat T (2003) Epidemiologic evidence of the protective effect of fruit and vegetables on cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr 78:559S–569

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2003) IARC Handbooks of cancer prevention: fruit and vegetables. IARC Press, Lyon

Statistics Canada (2002) Canada Food Stats.Food Statistics. 2

De Stefani E, Correa P, Fierro L, Fontham ET, Chen V, Zavala D (1993) The effect of alcohol on the risk of lung cancer in Uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2:21–26

Kvale G, Bjelke E, Gart J (1983) Dietary habits and lung cancer risk. International Journal of Cancer 31:397

Bandera EV, Freudenheim JL, Graham S, et al. (1992) Alcohol consumption and lung cancer in white males. Cancer Causes Control 3:361–369

Potter JD, McMichael AJ (1984) Alcohol, beer and lung cancer – a meaningful relationship? Int J Epidemiol 13:240–242

Hines LM, Rimm EB (2001) Moderate alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease: a review. Postgrad Med J 77:747–752

Meister KA, Whelan EM, Kava R (2000) The health effects of moderate alcohol intake in humans: an epidemiologic review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 37:261–296

Kabat GC, Wynder EL (1984) Lung cancer in nonsmokers. Cancer. 53:1214–1221

Bandera EV, Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, et al. (1997) Diet and alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in the New York State Cohort (United States). Cancer Causes Control 8:828–40

Prescott E, Gronbaek M, Becker U, Sorensen TI (1999) Alcohol intake and the risk of lung cancer: influence of type of alcoholic beverage. Am J Epidemiol 149:463–470

Gordon T, Kannel WB (1984) Drinking and mortality. The Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 120:97–107

Potter JD, Sellers TA, Folsom AR, McGovern PG (1992) Alcohol, beer, and lung cancer in postmenopausal women. The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 2:587–595

Koo LC (1988) Dietary habits and lung cancer risk among Chinese females in Hong Kong who never smoked. Nutr Cancer 11:155–172

Kubik AK, Zatloukal P, Tomasek L, et al. (2004) Dietary habits and lung cancer risk among non-smoking women. Eur J Cancer Prev. 13:471–480

Kubik A, Zatloukal P, Tomasek L, Pauk N, Petruzelka L, Plesko I (2004) Lung cancer risk among nonsmoking women in relation to diet and physical activity. Neoplasma. 51:136–143

Ruano-Ravina A, Figueiras A, Barros-Dios JM (2004) Type of wine and risk of lung cancer: a case–control study in Spain. Thorax 59:981–985

De Stefani E, Correa P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, et al. (2002) Alcohol intake and risk of adenocarcinoma of the lung. A case–control study in Uruguay. Lung Cancer 38:9–14

Pollack ES, Nomura AM, Heilbrun LK, Stemmermann GN, Green SB (1984) Prospective study of alcohol consumption and cancer. N Engl J Med 310:617–621

Ellison RC ( 2002) Balancing the risks and benefits of moderate drinking. Ann N Y Acad Sci 957:1–6

Bianchini F, Vainio H (2003) Wine and resveratrol: mechanisms of cancer prevention? Eur J Cancer Prev 12:417–425

Bhat KPL, Pezzuto JM (2002) Cancer chemopreventive activity of reservatrol. Annal N Y Acad Sci 957:210–229

Naimi T, Brown D, Brewer R, et al. (2005) Cardiovascular risk factors and condounders among nondrinking and moderate drinking US adults. Am J Preventive Med 28:369–373

Del Boca FK, Darkes J (2003) The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. [Review] [95 refs].Addiction 98:1

Chaikelson JS, Arbuckle TY, Lapidus S, Gold DP (1994) Measurement of lifetime alcohol consumption. J Studies Alcohol 55:133–140

Del Boca FK, Noll JA (2000) Truth or consequences: the validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. [Review] [42 refs]. Addiction 95:347

Polich JM (1982) The validity of self-reports in alcoholism research. Addict Behav 7:123–132

Boyle CA, Brann EA (1992) Proxy respondents and the validity of occupational and other exposure data. The Selected Cancers Cooperative Study Group. Am J Epidemiol 136:712–721

Graham P, Jackson R (1993) Primary versus proxy respondents: comparability of questionnaire data on alcohol consumption. Am J Epidemiol 138:443–452

Passaro KT, Noss J, Savitz DA, Little RE (1997) Agreement between self and partner reports of paternal drinking and smoking. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Int J Epidemiol 26:315–320

Nadalin V, Cotterchio M, McKeown-Eyssen G, Gallinger S (2003) Agreement between proxy- and case-reported information obtained using the self-administered Ontario Familial Colon Cancer Registry epidemiologic questionnaire. Chronic Dis Can 24:1–8

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork was supervised by Lesley Richardson. This study was supported by research and personnel support grants from Health Canada, the National Cancer Institute of Canada, the Institut de recherche en santé et sécurité au travail du Québec, the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In Study I, subjects were asked the usual frequency of consumption for ten different vegetable types:

-

carrots,

-

spinach,

-

broccoli,

-

corn,

-

lettuce, endive or watercress,

-

cabbage, cole slaw or sauerkraut,

-

green beans or peas,

-

Brussels sprouts,

-

tomatoes or tomato juice or food in tomato sauce,

-

green pepper,

-

and one fruit type:

-

apricot, peach, nectarine or prune.

In Study II, subjects reported their usual frequency of consumption for 13 vegetable categories:

-

tomatoes,

-

tomato sauce,

-

broccoli,

-

carrots,

-

mixed vegetables,

-

cabbage, cauliflower, asparagus, or Brussels sprouts,

-

lettuce or other leafy green vegetable,

-

spinach, watercress or other dark greens,

-

yellow squash, Swiss chard, or kale,

-

any other vegetable including green beans, corn or peas,

-

soups with vegetables,

-

sweet potatoes,

-

tomato or vegetable juice,

and for 12 fruit or fruit-juice types:

-

apples or pears,

-

orange, grapefruit or tangerine,

-

berries,

-

cantaloupe,

-

watermelon or other melon,

-

apricots, papaya or mango,

-

peaches, plums or nectarines,

-

dried apricots or peaches,

-

pumpkin,

-

other fruit,

-

orange, grapefruit or pineapple juice,

-

apple or other fruit juice or drink.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benedetti, A., Parent, ME. & Siemiatycki, J. Consumption of Alcoholic Beverages and Risk of Lung Cancer: Results from Two Case–control Studies in Montreal, Canada. Cancer Causes Control 17, 469–480 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-005-0496-y

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-005-0496-y