Abstract

Objective

African-Americans have a strikingly low prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health metrics of the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7 (LS7). This study was conducted to assess the impact of a community-based cardiovascular disease prevention intervention on the knowledge and achievement of cardiovascular health metrics among a marginalized African-American community.

Methods

Adult congregants (n = 37, 70 % women) from three African-American churches in Rochester, MN, participated in the Fostering African-American Improvement in Total Health (FAITH!) program, a theory-based, culturally-tailored, 16-week education series incorporating the American Heart Association’s LS7 framework. Feasibility testing included assessments of participant recruitment, program attendance, and retention. We classified participants according to definitions of ideal, intermediate, and poor cardiovascular health based on cardiac risk factors and health behaviors and calculated an LS7 score (range 0 to 14) at baseline and post-intervention. Knowledge of cardiac risk factors was assessed by questionnaire. Main outcome measures were changes in cardiovascular health knowledge and cardiovascular health components related to LS7 from baseline to post-intervention. Psychosocial measures included socioeconomic status, outlook on life, self-reported health, self-efficacy, and family support.

Results

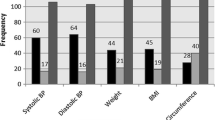

Thirty-six out of 37 recruited participants completed the entire program including health assessments. Participants attended 63.5 % of the education series and attendance at each session was, on average, 62 % of those enrolled. There was a statistically significant improvement in cardiovascular health knowledge (p < 0.02). A higher percentage of participants meeting either ideal or intermediate LS7 score categories and a lower percentage within the poor category were observed. Higher LS7 scores correlated with higher psychosocial measures ratings.

Conclusions

Although small, our study suggests that the FAITH! program is a feasible, community intervention promoting ideal cardiovascular health that has the potential to improve cardiovascular health literacy and LS7 among African-Americans.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322.

Minnesota Department of Health. Chronic Diseases and their risk factors in Minnesota: 2011. MN: St. Paul; 2011.

Shanedling S, Mehelich MJ, Peacock J. The Minnesota heart disease and stroke prevention plan 2011–2020. Minn Med. 2012;95(5):41–3.

Center for Health Statistics, Minnesota Department of Health. Populations of color in Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Health Status Report; 2009.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613.

American Medical Association. Commission to end health care disparities: unifying efforts to achieve quality care for all. Chicago, IL, 2011. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/eliminating-health-disparities/commission-end-health-care-disparities.page. Accessed March 11, 2016.

Association of Black Cardiologists, Incorporated. Community health advocacy: community programs. New York, New York, 2008. http://www.abcardio.org/CHA_communityprograms.php. Accessed March 11, 2016.

Koh HK, Blakey CR, Roper AY. Healthy people 2020: a report card on the health of the nation. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2475–6.

Bambs C, Kip KE, Dinga A, et al. Low prevalence of “ideal cardiovascular health” in a community-based population: the heart strategies concentrating on risk evaluation (Heart SCORE) study. Circulation. 2011;123(8):850–7.

Shay CM, Ning H, Allen NB, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003–2008. Circulation. 2012;125(1):45–56.

Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, et al. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(16):1690–6.

Folsom AR, Shah AM, Lutsey PL, et al. American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7: avoiding heart failure and preserving cardiac structure and function. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):970–6 .e972

Kim JI, Sillah A, Boucher JL, et al. Prevalence of the American Heart Association’s “ideal cardiovascular health” metrics in a rural, cross-sectional, community-based study: the heart of New Ulm project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(3):e000058.

Dong C, Rundek T, Wright CB, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health predicts lower risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death across whites, blacks, and hispanics: the northern Manhattan study. Circulation. 2012;125(24):2975–84.

Baruth M, Wilcox S. Multiple behavior change among church members taking part in the faith, activity, and nutrition program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(5):428–34.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, et al. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34.

Crook ED, Bryan NB, Hanks R, et al. A review of interventions to reduce health disparities in cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):204–8.

Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, et al. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):68–81.

DeHaven MJ, Ramos-Roman MA, Gimpel N, et al. The GoodNEWS (genes, nutrition, exercise, wellness, and spiritual growth) trial: a community-based participatory research (CBPR) trial with African-American church congregations for reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors–recruitment, measurement, and randomization. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(5):630–40.

Ralston PA, Lemacks JL, Wickrama KK, et al. Reducing cardiovascular disease risk in mid-life and older African Americans: a church-based longitudinal intervention project at baseline. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(1):69–81.

Yeary KH, Cornell CE, Turner J, et al. Feasibility of an evidence-based weight loss intervention for a faith-based, rural, African American population. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2011;8(6):A146.

United States Census Bureau. Quick facts, Rochester, MN. Washington, DC, 2014. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/2754880,2702908,27 . Accessed March 11, 2016.

Buta B, Brewer L, Hamlin DL, et al. An innovative faith-based healthy eating program: from class assignment to real-world application of PRECEDE/PROCEED. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(6):867–75.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

American Heart Association. My Life Check®, live better with Life’s Simple 7. Dallas, TX, 2014. http://mylifecheck.heart.org/. Accessed March 11, 2016.

Association of Black Cardiologists, Incorporated. 7 steps to a healthy heart. New York, New York, 2013. http://www.abc-patient.com/7Steps/index.html#/1/. Accessed March 11, 2016.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, 2008. On the move to better heart health for African Americans. (NIH Publication No. 08–5829). Bethesda, MD. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/other/chdblack/aariskfactors.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2016.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, 2008. Heart healthy home cooking African American Style. (NIH Publication No. 08–3792). Bethesda, MD. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/public/heart/cooking.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2016.

Mosca L, Mochari H, Christian A, et al. National study of women’s awareness, preventive action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113(4):525–34.

Underwood LG. Ordinary spiritual experience: qualitative research, interpretive guidelines, and population distribution for the daily spiritual experience scale. Archive for the Psychology of Religion. 2006;28:181–218.

Brewer LC, Hayes SN, Parker MW, et al. African American women’s perceptions and attitudes regarding participation in medical research: the Mayo Clinic/the Links, Incorporated partnership. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(8):681–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009. National health and nutrition examination survey: anthropometry procedures manual 3–21. Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2016.

Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 2: blood pressure measurement in experimental animals: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association council on high blood pressure research. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(3):e22–33.

Wartak SA, Friderici J, Lotfi A, et al. Patients’ knowledge of risk and protective factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(10):1480–8.

Kim Y, Park I, Kang M. Convergent validity of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ): meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(3):440–52.

Carlson JA, Sallis JF, Wagner N, et al. Brief physical activity-related psychosocial measures: reliability and construct validity. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(8):1178–86.

Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(9):800–11.

Thacker EL, Gillett SR, Wadley VG, et al. The American Heart Association Life’s simple 7 and incident cognitive impairment: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000635.

Norman GJ, Carlson JA, Sallis JF, et al. Reliability and validity of brief psychosocial measures related to dietary behaviors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:56.

Djousse L, Petrone AB, Blackshear C, et al. Prevalence and changes over time of ideal cardiovascular health metrics among African-Americans: the Jackson heart study. Prev Med. 2015;74:111–6.

Allicock M, Johnson LS, Leone L, et al. Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among members of black churches, Michigan and North Carolina, 2008-2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E33.

Kumanyika SK, Charleston JB. Lose weight and win: a church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among black women. Patient Educ Couns. 1992;19(1):19–32.

Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, et al. Healthy body/healthy spirit: a church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(5):562–73.

Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the black churches united for better health project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1390–6.

Wilcox S, Parrott A, Baruth M, et al. The faith, activity, and nutrition program: a randomized controlled trial in African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):122–31.

Kyryliuk R, Baruth M, Wilcox S. Predictors of weight loss for African-American women in the faith, activity, and nutrition (FAN) study. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(5):659–65.

Kalenderian E, Pegus C, Francis C, et al. Cardiovascular disease urban intervention: baseline activities and findings. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):282–7.

Conn VS, Phillips LJ, Ruppar TM, et al. Physical activity interventions with healthy minority adults: meta-analysis of behavior and health outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):59–80.

Wieland ML, Tiedje K, Meiers SJ, et al. Perspectives on physical activity among immigrants and refugees to a small urban community in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(1):263–75.

Wieland ML, Weis JA, Palmer T, et al. Physical activity and nutrition among immigrant and refugee women: a community-based participatory research approach. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(2):e225–32.

Mohamed AA, Hassan AM, Weis JA, et al. Physical activity among Somali men in Minnesota: barriers, facilitators, and recommendations. Am J Mens Health. 2014;8(1):35–44.

Tiedje K, Wieland ML, Meiers SJ, et al. A focus group study of healthy eating knowledge, practices, and barriers among adult and adolescent immigrants and refugees in the United States. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:63.

Balls-Berry J, Watson C, Kadimpati S, et al. Black men’s perceptions and knowledge of diabetes:a church-affiliated barbershop focus group study. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0094-y.

Formea CM, Mohamed AA, Hassan A, et al. Lessons learned: cultural and linguistic enhancement of surveys through community-based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(3):331–6.

Dodani S, Beayler I, Lewis J, et al. HEALS hypertension control program: training church members as program leaders. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2014;8:121–7.

Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–98.

Koh HK, Piotrowski JJ, Kumanyika S, et al. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(6):551–7.

Foraker RE, Shoben AB, Lopetegui MA, et al. Assessment of Life’s Simple 7 in the primary care setting: the stroke prevention in healthcare delivery environments (SPHERE) study. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;38(2):182–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to local Rochester, MN, participating churches including church leadership (Pastor Donald Barlow of Rochester Community Baptist Church, Pastor Kenneth Rowe of Christ’s Church of the Jesus Hour, and Pastor Lerone Shepard of Christway Full Gospel Ministries) and FAITH! Partners (Mrs. Consuelo Cohen, Mrs. Frances Ellis, Mrs. Jacqueline Johnson, and Mr. D.C. Mangum). The authors gratefully acknowledge all study participants, church auxiliaries and Mayo Clinic faculty/staff who devoted much time and offered unwavering support for the program. The authors would also like to show gratitude to the Mayo Medical School and University of Minnesota School of Nursing students for volunteering their time for the study health assessments and acknowledge research assistants Mrs. Lea Dacy and Mr. Miguel Valdez Soto for their administrative assistance and participant navigation services. In memory of our colleague, Mr. D.C. Mangum, outstanding leader, administrator, and friend, who served as a role model for dedicated community service, civic responsibility, and activism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This study was supported by the Mayo Clinic Office of Health Disparities Research, Mayo Clinic Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic Biobank, Barbara Woodward Lips Patient Education Center, and the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (UL1TR000135).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02235896

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 85 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brewer, L.C., Balls-Berry, J.E., Dean, P. et al. Fostering African-American Improvement in Total Health (FAITH!): An Application of the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7™ among Midwestern African-Americans. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 269–281 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0226-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0226-z