Abstract

The proto-oncogenic protein c-Myb is an essential regulator of hematopoiesis and is frequently deregulated in hematological diseases such as lymphoma and leukemia. To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying the aberrant expression of c-Myb in myeloid leukemia, we analyzed and compared c-myb gene transcriptional regulation using two cell lines modeling normal hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and transformed myelomonocytic blasts. We report that the transcription factors HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx1 and Pbx2 bind in vivo to the c-myb locus and maintain its expression through different mechanisms in HPCs and leukemic cells. Our analysis also points to a critical role for Pbx2 in deregulating c-myb expression in murine myeloid cells cotransformed by the cooperative activity of HoxA9 and Meis1. This effect is associated with an intronic positioning of epigenetic marks and RNA polymerase II binding in the orthologous region of a previously described alternative promoter for c-myb. Taken together, our results could provide a first hint to explain the abnormal expression of c-myb in leukemic cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

c-Myb is a key regulator of hematopoiesis, influencing aspects of proliferation, differentiation and programmed cell death throughout the hematopoietic hierarchy. Abundantly expressed in the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell compartments, c-Myb is downregulated as cells progress toward terminal differentiation.1, 2, 3 Confirming its crucial role in hematopoiesis, the constitutive ablation of the c-myb gene results in a failure to develop an adult blood system.4 Although the expression and function of c-Myb have been extensively studied, the mechanisms underlying its transcriptional regulation remain unclear. To date, the murine c-myb gene has been described to be constitutively active. Its downregulation during differentiation has been attributed to a block in transcriptional elongation within the first intron combined with posttranscriptional modulation through the action of specific micro RNAs.5, 6, 7, 8 However, to our knowledge, no studies have addressed the mechanisms promoting and maintaining high levels of c-myb expression in hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs), where c-Myb has critical functions.2

The need to maintain c-Myb levels above a minimum threshold in HPCs has been demonstrated in vivo using genetically engineered mouse models. Conditional loss of c-myb gene function results in a depletion of the HPC pool,9 and the HPC compartment is also profoundly affected in mice homozygous for either a constitutive knock down allele10, 11 or hypomorphic variants of c-myb.12, 13 In these cases, the respective reduced level or compromised activity of c-Myb correlate with the loss of stem cell quiescence and the acquisition of a myeloproliferative phenotype characterized by increased peripheral monocytes and platelets together with corresponding aberrations in the bone marrow. This phenotype, reminiscent of the myeloproliferative disorder essential thrombocythemia, adds to a growing body of evidence linking c-Myb deregulation to hematological disorders. Likewise, aberrant c-Myb expression has been circumstantially associated with the development of several types of leukemia including chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Although high levels of c-myb transcripts have been directly related to chromosomal translocation or duplication affecting the c-myb locus in subsets of acute lymphoblastic leukemia,14, 15 the mechanisms underlying abnormal expression of c-myb in chronic myeloid leukemia or AML remain unclear. Studies on a model of MLL-ENL-induced AML demonstrated a critical role for c-Myb in the transforming potential of the fusion protein.16 The authors suggest that, albeit having no intrinsic transforming activity, c-Myb potentially serve as an entry point to influence central growth control. Although the precise mechanism affecting c-myb gene expression in these cells was not determined, it was suggested that the transcription factors HoxA9 and myeloid ecotropic viral integration site (Meis1) could link MLL-ENL activity to c-myb transcription. How HoxA9 and Meis1 may influence c-myb expression in these cells or in normal HPCs remains to be defined.

The Hox proteins represent a family of transcription factors containing a DNA-binding motif of 60 amino acids known as the homeodomain. In addition to their role in embryonic development,17 considerable evidence shows the importance of HoxA proteins as key regulators of hematopoiesis. Among the hoxA genes, highly expressed in hematopoietic progenitors, hoxA9 has been linked to a variety of leukemias in which its elevated expression is often considered to be a marker of poor prognosis.18 The HoxA9 protein is able to form heterodimers or heterotrimers with members of the TALE (3-amino-acids-loop-extension) protein families Meis (myeloid ecotropic viral integration site) and Pbx (pre-B cell leukemia homeobox). Through these complexes, the TALE factors influence HoxA9 binding affinity and specificity.19 It is therefore not surprising that like hoxA9, expression of both meis1 and pbx1 has also been closely linked with leukemogenesis. The meis1 gene locus was first identified in the BHX-2 mouse model as a site of viral integration in 15% of the induced leukemias20 and its role in leukemogenesis was subsequently well-established.21 In human Pre-B ALL, the pbx1 gene was identified as a component of the t(1,19) chromosomal translocation that results in the generation of the E2A-Pbx1 transforming protein.21, 22 Importantly, the collaboration between HoxA9 and TALE proteins is suggested to be essential for their respective transforming capacities. In particular, Meis1 was shown to drastically lower the latency of HoxA9-mediated transformation, leading to the rapid onset of a fully penetrant AML in transplantable mouse models.23

Here, we assess the role of HoxA9 and Meis1 in c-myb gene regulation in AML and HPCs using representative cell line models. The HPC7 line is a nonleukemic HPC line ectopically expressing the LIM-homeodomain protein Lhx2, which retains multilineage differentiation capacity in response to specific cytokines.24 Importantly, the Lhx2 protein, which allows culture and expansion of the cells in an undifferentiated state, has been shown not to alter HPC properties.25 We also used the FMH9 line, derived from primary HoxA9/Meis1-transformed bone marrow progenitors, as an AML model. By comparing c-myb regulation in the HPC7 and FMH9 cellular systems, we demonstrate that the c-myb gene is a direct target for HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx1 and Pbx2. Our analysis uncovers major differences in the regulation of c-myb transcription in the HoxA9/Meis1-transformed cell line compared with the HPC model, which could explain the overexpression of c-myb observed in leukemic cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and differentiation

HPC7 cells, kindly provided by Dr Lief Carlsson (Umea, Sweden), were cultured in Stem Pro 34 medium (Invitrogen Ltd, Paisley, UK) and recombinant stem cell factor (SCF) (100 ng/ml). To induce myeloid differentiation, stem cell factor was replaced by a mixture of recombinant cytokines: 20 ng/ml G-CSF, 10 ng/ml GM-CSF, 10 ng/ml IL-3 and 10 ng/ml IL-6. FMH9 cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 ng/ml stem cell factor, 5 ng/ml GM-CSF, 5 ng/ml IL-3 and 5 ng/ml IL-6. All the cytokines were purchased from Peprotech EC (London, UK).

Transfection and plasmids

20 × 106 HPC7 cells or 5 × 106 FMH9 cells were electroporated using the Amaxa transfection Kit (Biosystems, Warrington, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression vector for Pbx1 and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) for HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx1 and Pbx2 were purchased from Origene (Cambridge, UK). The plasmids encoding the transcription factors HoxA9 and Meis1 were as described.16 The cDNA for mouse Pbx2 was amplified by PCR and introduced into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen Ltd).

Nuclease hypersensitive site mapping

Cells were washed with PBS and nuclei prepared by resuspension in 1 ml aliquots of digestion buffer (Tris-HCl 15 mM pH7.5, NaCl 15 mM, KCl 60 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, glucose 300 mM, EGTA 0.5 mM, NP40 0.1%). For digestion of nuclei, 0–60 units of DNase I were added to each aliquot and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The reaction was terminated by addition of 330 μl of stop solution (EDTA 100 mM, SDS 4%). RNA and proteins were sequentially digested by addition of 100 μg of RNase A and 100 μg of proteinase K, incubated respectively for 1 h and overnight at 37 °C. Following phenol/chloroform extractions, DNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in water. Quantitative-PCR (Q-PCR) was performed on 100 ng of undigested and DNAseI-treated DNA.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (X-ChIP)

Cross linking and X-ChIP were performed as previously described.26 Antibodies against HoxA9 (N-20 X), Meis1 (C-17 X), Pbx1 (P-20 X) or Pbx2 (G-20 X) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Heidelberg, Germany). Antibodies against histone marks were made in-house.

ChIP on chip analysis

A series of 60-base-long oligonucleotides were designed to span the c-myb locus and compared against the mouse genome, using BlastN, to avoid repeated or crossreacting sequences. The oligonucleotides were arrayed in triplicate onto Codelink slides (Amersham GE healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using a Microgrid II arrayer (Biorobotics/Genomic Solutions, Cambridge, UK) and stored at room temperature until hybridized. Hybridizations were performed as previously described by Follows et al.27

Results

c-myb cis-regulatory domains encompass multiple Hox and TALE consensus binding sites

In order to locate potential Hox-TALE functional binding sites, we set out to identify cis-regulatory modules based on their sensitivity to nuclease digestion and a corresponding location of consensus-binding-site sequences. Nuclei from HPC7 cells and HoxA9/Meis1-transformed FMH9 cells were digested with up to 60 units of DNAse I before DNA extraction. Following an initial Southern blot analysis encompassing a wide region of the c-myb locus, our analysis was refined around regions of interest using a Q-PCR-based method (Figure 1). This rating of nuclease digestion highlighted the presence of several sites of hypersensitivity in the promoter (HS-B) and first intron (HS-C and HS-D), each encompassing a number of consensus sites for the binding of Hox and TALE proteins. For instance, nine consensus sites for binding of HoxA9–TALE complexes, such as HoxA9–Meis1 complexes, were located within the intronic HS-D region, a large nuclease sensitive area that displays high degrees of sequence conservation across species. The patterns of nuclease hypersensitivity were broadly similar in HPC7 and FMH9 cells, although some region-specific variations appear, for example at the upstream end of region HS-D.

Analysis of DNAseI sensitivity at the c-myb locus. Nuclei from both HPC7 and FMH9 cells were treated with 0 or 60 units of DNAseI and the resulting purified DNA was used as a template for Q-PCR reactions across regions of interest. The ratio between digested and undigested samples reflects the extent of hypersensitivity across regions covered by the PCR amplicons. The dashed lines indicate the basal level of digestion across the locus. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. The defined regions of hypersensitivity and a representation of the first and second exon of the c-myb transcript are shown at the bottom of the figure.

HoxA9 and Meis1 participate in the regulation of c-myb gene expression

To investigate the extent to which HoxA9 and Meis1 contribute to the regulation of c-myb transcription, we manipulated their levels through shRNA knockdown and overexpression in both HPC7 and FMH9 cells. shRNA-mediated silencing of HoxA9 and Meis1 were achieved by transient transfection (Supplementary Figure S1a) and c-myb RNA levels were measured 24 h later by Q-PCR (Figure 2a). A reduction of HoxA9 or Meis1 led to a decrease in c-myb expression in both normal and leukemic cells. In contrast, enforced expression of HoxA9 and Meis1 (Supplementary Figure S1b and c), singly or in combination, failed to influence c-myb expression in the HPC line (Figure 2b). We therefore conclude that HoxA9 and Meis1, although required to maintain c-myb expression, cannot further activate c-myb transcription when overexpressed in the HPC cell line.

Effect of the modulation of HoxA9 and Meis1 expression levels on c-myb RNA expression. Q-PCR analysis of c-myb mRNA expression was performed on HPC7 and FMH9 cells transfected with HoxA9 or Meis1 shRNA vectors (a) or corresponding expression vectors. (b) q-PCR results were normalized against the 18S gene and compared with the control samples transfected with scrambled shRNA. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Results are representative of four independent experiments. ***P<0.001; **P<0.01.

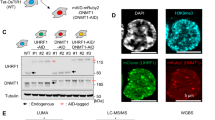

Pbx1 and Pbx2 have distinct roles in the regulation of the c-myb gene

As effective HoxA9- and Meis1-mediated gene regulation can require the cooperative function of a member of the Pbx family, we next assessed the role of Pbx1 and Pbx2 in c-myb gene regulation. The efficiency of knock down or overexpression of Pbx1 and Pbx2 in HPC7 and FMH9 cells is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S2. ShRNA-mediated knock down of Pbx1 resulted in reduced c-myb RNA expression in both HPC7 and FMH9 cells, an effect enhanced when HoxA9 and Meis1 were cosilenced (Figure 3a). Correspondingly, overexpression demonstrated the cooperation between Hox and TALE proteins in regulating c-myb expression in HPCs. Although Pbx1 overexpression alone did not increase c-myb RNA levels, the combined enforced expression of Pbx1/Meis1, Pbx1/HoxA9 and Pbx1/Meis1/HoxA9 resulted in 4-, 7- and 14-fold increases, respectively, of c-myb mRNA level in HPC7 cells (Figure 3b). Pbx1 therefore acts in synergy with both HoxA9 and Meis1 in relation to c-myb gene activation in the HPC line. In contrast, enforced expression of Pbx1 does not increase c-myb RNA levels in FMH9 cells (Figure 3b). Similar modulations of Pbx2 expression revealed drastic and opposite effects in normal versus leukemic cells. When overexpressed alone or in combination with HoxA9 and Meis1 in HPC7 cells, Pbx2 acts as a repressor of c-myb expression, while it displays activating function in FMH9 cells (Figures 3c and d). In fact, in the FMH9 cells, Pbx2 function appears to substitute for Pbx1 ability to cooperate with overexpressed HoxA9 and Meis1 in activating c-myb expression.

Effect of the modulation of Pbx1 and Pbx2 expression levels on c-myb mRNA. q-PCR analysis of c-myb mRNA expression was performed on HPC7 and FMH9 cells transfected with shRNA vectors for Pbx1, HoxA9 and Meis1 (a) or corresponding expression vectors (b). Similarly, vectors expressing Pbx2 shRNA (c) or Pbx2 (d) were used to modulate Pbx2 expression in both cell types alone or in combination. q-PCR results were normalized against the 18S gene and compared with the control samples transfected with scrambled shRNA. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Results are representative of four independent experiments. ***P<0.001; **P<0.01.

Differential recruitment of HOX-TALE proteins at the c-myb locus

We next tested HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx1 and Pbx2 in vivo binding to the c-myb locus using crosslinked chromatin immunoprecipitations (X-ChIP). DNA samples generated by ChIP from HPC7 or FMH9 chromatin were analyzed by Q-PCR using primers covering the defined regions of nuclease hypersensitivity and relative enrichments were determined by comparison with matched IgG ChIP controls. HoxA9, Meis1 and Pbx1 were found associated to the c-myb HS-D domain, although their precise locations varied between HPCs and transformed cells (Figure 4). No binding of these proteins was found on HS-A, HS-B or HS-C. Furthermore, reflecting its opposite effect on c-myb regulation, Pbx2 binding was found to be dramatically different between HPCs and leukemic cell line. In HPC7 cells, Pbx2 was found associated with HS-A and HS-C, whereas in FMH9 cells, it was found to be located on the HS-D region. Hence, the repressive activity of Pbx2 on c-myb expression correlates with its binding to the proximal promoter and first intron of the gene, while its activating function is associated with its co-location with HoxA9 and Meis1 at the HS-D region, immediately upstream the second exon.

In vivo binding of HoxA9, Meis1 and Pbx1/2 at the c-myb promoter and first intron. X-ChIP experiments were performed on chromatin obtained from both HPC7 and FMH9 cells, and using antibodies directed against HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx1 or Pbx2. Purified immunoprecipitated DNA was used as a template for q-PCR amplifications and relative enrichments were measured against the control IgG ChIP material. The histograms represent the levels of enrichment at locations relative to the c-myb ATG and the width of the bars reflect the length of the PCR amplicons. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Epigenetic modifications and PolII recruitment suggest alternative c-myb promoter usage in normal and leukemic cells

Our data suggested that most of the differential features of c-myb regulation comparing HPC7 and FMH9 cells are associated with the HS-D region. This sequence of the c-myb gene is highly conserved amongst mammals and has previously been described as an alternative promoter in human cells.28 In order to locate potential sites of transcriptional initiation, we mapped two promoter-related epigenetic marks (H3K9ac and H3K4me3) and identified sites of RNA poIymerase II (PolII) occupancy in vivo. ChIP-on-chip analyses revealed that both histone modifications were broadly enriched over the c-myb promoter and first intron in HPC7 cells but restricted to the intronic HS-D domain in FMH9 cells (Figure 5a). Mirroring this difference, RNA polII X-ChIP analysis revealed enrichments at the c-myb promoter in HPC7 cells, while it was bound preferentially upstream of exon 2 in FMH9 cells (Figure 5b). Taken together, these results might suggest that an alternative promoter in the intron immediately upstream exon 2 could drive the expression of c-myb in myelomonocytic FMH9 blasts.

Epigenetic environment and PolII recruitment at the c-myb promoter and first intron. ChIP-on-chip experiments were performed using chromatin obtained from HPC7 and FMH9 cells and antibodies directed against H3K4ac and H3K4me3 (a). Enrichment values were calculated as fold-enrichment over the mean intensity across the locus and expressed as log base 2. The position of the hypersensitive regions and c-myb exons 1 and 2 are indicated. Representation of X- ChIP experiments using an antibody against PolII and chromatin derived from HPC7 and FMH9 (b). The relative enrichments associated with the HS-B and HS-D regions were determined by q-PCR against the control IgG ChIP material. Ratio between the transcriptional levels of exon 2 compared with exon 1 of the c-myb gene performed in HPC7, FMH9, HPC7 D4 and HPC7 D6 (c). The table represents the relative level of expression measured at exon 1 (ex1) and exon 2 (ex2) of the c-myb gene. q-PCR results were normalized against the 18S gene.

However, PolII occupancy could also be reflecting the stage of lineage differentiation of FMH9 cells compared with HPC7 rather than being a feature of the transformed state. In order to rule out this possibility, we looked into the recruitment of PolII in differentiated HPC7 expressing the myeloid markers CD11b and Gr1 after 4 (HPC7 D4) or 6 days (HPC7 D6) in presence of GM-CSF, GC-CSF, IL-3 and IL-6 (Supplementary Figure S3a). In contrast to FMH9 cells, binding of PolII was preferentially found on exon 1 (ex1) and to a lesser degree upstream of exon 2 in HPC7 derived cells (Supplementary Figure S3b). Thus, PolII occupancy as observed in FMH9 cells appears to reflect a leukemia-related mechanism rather than a myelomonocytic lineage-associated phenomenon.

To further validate the hypothesis of an alternative promoter, we first tried a direct approach using a 5′-RACE PCR method but were unsuccessful in obtaining products starting before exon 3, probably owing to the presence of a tertiary structure interfering with the PCR-elongation process. Therefore, to further establish if Pbx differential binding could override an elongation attenuation signal or actually activates an intronic alternative promoter, we proceeded to measure the levels of expression of c-myb exon 1 and exon 2 by Q-PCR. Indicative of the relative level of transcription upstream and downstream of the elongation attenuation signal, the ratio of expression (ex1/ex2) were calculated for sorted primary KSL (c-kit+Sca-1+Lin-) HSC, HPC7 and FMH9 cells (Figure 5c). Noticeably, KSL and HPC7 cells, which display comparable expression patterns with respect to c-myb, hoxA9, meis1, pbx1 and pbx2 (Supplementary Figure S3c), also revealed similar c-myb ex1/ex2 ratios. Indicating the overrepresentation of exon 1 compared with exon 2, these ratios are consistent with the possibility of a mild elongation attenuation occurring within the intron 1. In contrast, a ex1/ex2 ratio of 0.28 demonstrates the overrepresentation of exon 2 compared with exon 1 in FMH9 cells. Associating with high levels of H3K9ac, H3K4me3 and PolII occupancy on the first intron of the c-myb gene, this result substantiates the use of an alternative intronic promoter in FMH9 cells that may override a block in transcription elongation and could explain the abnormal expression of c-myb in this model for AML.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate the direct involvement of HoxA9 and its cofactors Meis1, Pbx1 and Pbx2 in the transcriptional regulation of c-myb in HPCs and HoxA9/Meis1-transformed myeloblastic cellular models. In the HPC cell line, we show that Pbx1 acts in synergy with HoxA9 and Meis1 to induce c-myb expression, although Pbx2 displays a repressive activity. In contrast, in the leukemic model, Pbx2 acts as an activator of c-myb transcription and seems to substitute for Pbx1. In those cells, Pbx2 colocates with HoxA9 and Meis1 upstream of c-myb exon 2 in a region that appears to display promoter properties.

Noticeably, following previous work on the CCRF-CEM lymphoid leukemia cell line29 and the cloning of a c-myb cDNA, which 5' suggested alternative transcription initiation within c-myb intron 1, the human hortologue region was described by Jacobs and colleague as an alternative promoter relating to several transcription start sites.28

Specific cooperative interactions between Pbx and Hox proteins have been shown to modulate the properties of Hox proteins and influence their DNA-binding specificities.30 Amongst the Hox proteins, HoxA9 and HoxA10 paralogs exhibit the capacity to interact with either Meis or Pbx proteins to form DNA-binding complexes with respective affinities for HoxA/TALE consensus sequences.19 Meis1 can also bind both HoxA9 and Pbx, which allows for the formation of HoxA9/Meis1 or Meis1/Pbx dimeric complexes31 and HoxA9/Meis1/Pbx trimeric complexes.32 We have observed that HoxA9, Meis1 and Pbx bind the c-myb locus on different HoxA/TALE consensus sequences in HPC and leukemic cell lines. The differences of binding sites, in particular in the intronic HS-D region, could reflect the formation of different functional complexes in leukemic cells that express high levels of HoxA9 and Meis1. Interestingly, our result contrasts with the recent work of Huang et al.,33 which did not identify these binding, suggesting that the recruitment of HoxA9 and Meis1 may be subject to external signals and culture conditions.

Imbalances in the expression of HoxA9 and Meis1 are observed in over 50% of human AML and nearly all ALL-containing translocations of the MLL gene.34, 35, 36, 37 In addition, both proteins cooperate in inducing AML-like leukemia in mice.23 Similarly, functional studies have highlighted the collaborative role of Pbx, whose synergistic function with HoxA9 was shown to be crucial for myeloid transformation.38 However, the different Pbx family members appear to participate in leukemogenesis to different extents: Pbx1 exhibits no synergistic effect with HoxA9 and Meis1 in transforming primary bone marrow cells and inducing leukemia in a murine transplantable AML model.23 A possible explanation for this can be found in the work of Shen and colleagues who showed that HoxA9 and Meis1 preferentially form complexes with Pbx2 in a myeloid environment.32 Accordingly, Pbx2 or Pbx3 were found to be crucial to MLL transformation, although Pbx1, which is expressed to a lesser extent in myeloid cells, proved to be dispensable.39 It is therefore perhaps not surprising that we find that Pbx2, but not Pbx1, has a profound effect on the regulation of c-myb expression in myeloblastic cells. Adding to the fact that c-myb expression was reported to be a crucial downstream event of MLL transformation,16 our findings add to the growing body of evidence linking Pbx2 activity to leukemogenesis. However, a key role of Pbx2 in normal or deregulated hematopoiesis contrasts with the apparent lack of phenotype observed in Pbx2 gene knockout mice,40 although this lack of effect could be due to redundancy with the other member of the Pbx family. Further studies involving Pbx2 conditional knockout mice models would unveil the detailed role of Pbx2 in hematopoiesis.

Remarkably, although the repressive activity of Pbx2 on c-myb expression in HPCs is associated with its recruitment to the promoter and the mid-intronic region, its activating function in leukemic myeloid cells correlates with its binding to the HS-D regulatory module, together with HoxA9, Meis1 and RNA PolII. Contrasting with its persistent association with the c-myb promoter in normal differentiated myeloid cells derived from the HPC7 cells, the switch in RNA PolII occupancy to the HS-D region seems to reflect a leukemia-related phenomenon. Such a feature could be a direct consequence of the inappropriate expression of HoxA9 and Meis1 in the committed cells, which is likely to create an environment that favors Pbx2 and RNA PolII recruitment leading to transcriptional activation of the c-myb gene despite an attenuation mechanism. In this respect, our findings could be a first hint regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying the deregulation of the c-myb gene in certain types of myeloid leukemia. In the transformed cells, HoxA9, Meis1, Pbx and RNA PolII binding to the HS-D domain correlate with the repositioning of promoter-related epigenetic modifications immediately upstream of c-myb exon 2. Incidentally, this highly conserved region corresponds to a second c-myb promoter and cluster of transcription start sites that has been characterized in human cells.28 Positioned downstream of the c-myb elongation attenuation domain,5 this alternative promoter could drive c-myb expression in the FMH9 cells although overriding the normal downregulatory mechanism associated with the differentiation process. Although the transformed cells display a promyeloblast phenotype, it is probable that earlier progenitors constituted the population initially targeted by HoxA9 transforming activity. Using the HPC7 as a model of nontransformed early progenitors, we propose that, within the transformation process, HoxA9 overexpression participates in counteracting c-Myb downregulation associated with further commitment to the myeloid lineage rather than activating c-myb expression as reported by others in different systems.16, 33, 41 However, the precise mechanisms underlying the abnormal expression of c-myb observed in several types of leukemia could have different origins. Indeed, considering the central role of c-myb during the different stages of the hematopoiesis, it would not be surprising to find that various transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms are involved in the control of its expression. Further studies using in vitro and in vivo leukemic models, as well as other models of hematopoietic diseases would be required to address these questions.

References

Oh IH, Reddy EP . The myb gene family in cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene 1999; 18: 3017–3033.

Greig KT, Carotta S, Nutt SL . Critical roles for c-Myb in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Semin Immunol 2008; 20: 247–256.

Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ . MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 523–534.

Mucenski ML, McLain K, Kier AB, Swerdlow SH, Schreiner CM, Miller TA et al. A functional c-myb gene is required for normal murine fetal hepatic hematopoiesis. Cell 1991; 65: 677–689.

Bender TP, Thompson CB, Kuehl WM . Differential expression of c-myb mRNA in murine B lymphomas by a block to transcription elongation. Science 1987; 237: 1473–1476.

Watson RJ . A transcriptional arrest mechanism involved in controlling constitutive levels of mouse c-myb mRNA. Oncogene 1988; 2: 267–272.

Barroga CF, Pham H, Kaushansky K . Thrombopoietin regulates c-Myb expression by modulating micro RNA 150 expression. Exp Hematol 2008; 36: 1585–1592.

Lu J, Guo S, Ebert BL, Zhang H, Peng X, Bosco J et al. MicroRNA-mediated control of cell fate in megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors. Dev Cell 2008; 14: 843–853.

Lieu YK, Reddy EP . Conditional c-myb knockout in adult hematopoietic stem cells leads to loss of self-renewal due to impaired proliferation and accelerated differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 21689–21694.

Emambokus N, Vegiopoulos A, Harman B, Jenkinson E, Anderson G, Frampton J . Progression through key stages of haemopoiesis is dependent on distinct threshold levels of c-Myb. EMBO J 2003; 22: 4478–4488.

Garcia P, Clarke M, Vegiopoulos A, Berlanga O, Camelo A, Lorvellec M et al. Reduced c-Myb activity compromises HSCs and leads to a myeloproliferation with a novel stem cell basis. EMBO J 2009; 28: 1492–1504.

Carpinelli MR, Hilton DJ, Metcalf D, Antonchuk JL, Hyland CD, Mifsud SL et al. Suppressor screen in Mpl−/− mice: c-Myb mutation causes supraphysiological production of platelets in the absence of thrombopoietin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 6553–6558.

Sandberg ML, Sutton SE, Pletcher MT, Wiltshire T, Tarantino LM, Hogenesch JB et al. c-Myb and p300 regulate hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Dev Cell 2005; 8: 153–166.

Clappier E, Cuccuini W, Kalota A, Crinquette A, Cayuela JM, Dik WA et al. The C-MYB locus is involved in chromosomal translocation and genomic duplications in human T-cell acute leukemia (T-ALL), the translocation defining a new T-ALL subtype in very young children. Blood 2007; 110: 1251–1261.

Lahortiga I, De Keersmaecker K, Van Vlierberghe P, Graux C, Cauwelier B, Lambert F et al. Duplication of the MYB oncogene in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 593–595.

Hess JL, Bittner CB, Zeisig DT, Bach C, Fuchs U, Borkhardt A et al. c-Myb is an essential downstream target for homeobox-mediated transformation of hematopoietic cells. Blood 2006; 108: 297–304.

Pearson JC, Lemons D, McGinnis W . Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet 2005; 6: 893–904.

Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK . Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene 2007; 26: 6766–6776.

Shen WF, Montgomery JC, Rozenfeld S, Moskow JJ, Lawrence HJ, Buchberg AM et al. AbdB-like Hox proteins stabilize DNA binding by the Meis1 homeodomain proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1997; 17: 6448–6458.

Moskow JJ, Bullrich F, Huebner K, Daar IO, Buchberg AM . Meis1, a PBX1-related homeobox gene involved in myeloid leukemia in BXH-2 mice. Mol Cell Biol 1995; 15: 5434–5443.

Nourse J, Mellentin JD, Galili N, Wilkinson J, Stanbridge E, Smith SD et al. Chromosomal translocation t(1;19) results in synthesis of a homeobox fusion mRNA that codes for a potential chimeric transcription factor. Cell 1990; 60: 535–545.

Kamps MP, Baltimore D . E2A-Pbx1, the t(1;19) translocation protein of human pre-B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, causes acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13: 351–357.

Wang GG, Pasillas MP, Kamps MP . Persistent transactivation by meis1 replaces hox function in myeloid leukemogenesis models: evidence for co-occupancy of meis1-pbx and hox-pbx complexes on promoters of leukemia-associated genes. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 3902–3916.

Pinto do OP, Kolterud A, Carlsson L . Expression of the LIM-homeobox gene LH2 generates immortalized steel factor-dependent multipotent hematopoietic precursors. EMBO J 1998; 17: 5744–5756.

Pinto do OP, Richter K, Carlsson L . Hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells immortalized by Lhx2 generate functional hematopoietic cells in vivo. Blood 2002; 99: 3939–3946.

Lorvellec M, Dumon S, Maya-Mendoza A, Jackson D, Frampton J, Garcia P . B-Myb is critical for proper DNA duplication during an unperturbed S phase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2010; 28: 1751–1759.

Follows GA, Dhami P, Gottgens B, Bruce AW, Campbell PJ, Dillon SC et al. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genomic microarray mapping of DNaseI hypersensitive sites. Genome Res 2006; 16: 1310–1319.

Jacobs SM, Gorse KM, Westin EH . Identification of a second promoter in the human c-myb proto-oncogene. Oncogene 1994; 9: 227–235.

Westin EH, Gorse KM, Clarke MF . Alternative splicing of the human c-myb gene. Oncogene 1990; 5: 1117–1124.

Moens CB, Selleri L . Hox cofactors in vertebrate development. Dev Biol 2006; 291: 193–206.

Kroon E, Krosl J, Thorsteinsdottir U, Baban S, Buchberg AM, Sauvageau G . Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. EMBO J 1998; 17: 3714–3725.

Shen WF, Rozenfeld S, Kwong A, Kom ves LG, Lawrence HJ, Largman C . HOXA9 forms triple complexes with PBX2 and MEIS1 in myeloid cells. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19: 3051–3061.

Huang Y, Sitwala K, Bronstein J, Sanders D, Dandekar M, Collins C et al. Identification and characterization of Hoxa9 binding sites in hematopoietic cells. Blood 2012; 119: 388–398.

Lawrence HJ, Rozenfeld S, Cruz C, Matsukuma K, Kwong A, Komuves L et al. Frequent co-expression of the HOXA9 and MEIS1 homeobox genes in human myeloid leukemias. Leukemia 1999; 13: 1993–1999.

Rozovskaia T, Feinstein E, Mor O, Foa R, Blechman J, Nakamura T et al. Upregulation of Meis1 and HoxA9 in acute lymphocytic leukemias with the t(4: 11) abnormality. Oncogene 2001; 20: 874–878.

Zeisig BB, Milne T, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Schreiner S, Martin ME, Fuchs U et al. Hoxa9 and Meis1 are key targets for MLL-ENL-mediated cellular immortalization. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 617–628.

Faber J, Krivtsov AV, Stubbs MC, Wright R, Davis TN, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M et al. HOXA9 is required for survival in human MLL-rearranged acute leukemias. Blood 2009; 113: 2375–2385.

Schnabel CA, Jacobs Y, Cleary ML . HoxA9-mediated immortalization of myeloid progenitors requires functional interactions with TALE cofactors Pbx and Meis. Oncogene 2000; 19: 608–616.

Wong P, Iwasaki M, Somervaille TC, So CW, Cleary ML . Meis1 is an essential and rate-limiting regulator of MLL leukemia stem cell potential. Genes Dev 2007; 21: 2762–2774.

Selleri L, DiMartino J, van Deursen J, Brendolan A, Sanyal M, Boon E et al. The TALE homeodomain protein Pbx2 is not essential for development and long-term survival. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 5324–5331.

Whelan JT, Ludwig DL, Bertrand FE . HoxA9 induces insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2008; 22: 1161–1169.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lief Carlsson (Umea, Sweden) for providing the HPC7 cell line, Roger Bird (Birmingham, UK) for cell sorting, Richard Auburn (Flychip, Cambridge) for printing the custom arrays and Berthold Göttgens (Institute of Medical Research, Cambridge) for his helpful discussions. This work was supported by Leukemia and Lymphoma Research and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Blood Cancer Journal website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Dassé, E., Volpe, G., Walton, D. et al. Distinct regulation of c-myb gene expression by HoxA9, Meis1 and Pbx proteins in normal hematopoietic progenitors and transformed myeloid cells. Blood Cancer Journal 2, e76 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2012.20

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2012.20

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Reversal of MYB-dependent suppression of MAFB expression overrides leukaemia phenotype in MLL-rearranged AML

Cell Death & Disease (2023)

-

Overexpression of HOXA9 upregulates NF-κB signaling to promote human hematopoiesis and alter the hematopoietic differentiation potentials

Cell Regeneration (2021)

-

High WBP5 expression correlates with elevation of HOX genes levels and is associated with inferior survival in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Distal regulation of c-myb expression during IL-6-induced differentiation in murine myeloid progenitor M1 cells

Cell Death & Disease (2016)

-

Role of HOXA9 in leukemia: dysregulation, cofactors and essential targets

Oncogene (2016)