Abstract

Background:

The development of obesity through childhood, often characterized by using body mass index (BMI), has received much recent interest because of the rapidly increasing levels of obesity worldwide. However, the extent to which the BMI trajectory in the first year of life (the BMI ‘peak’ in particular) is associated with BMI in later childhood has received little attention.

Subjects:

The Uppsala Family Study includes 602 families, comprising mother, father and two consecutive singleton offspring, both of whom were delivered at the Uppsala Academic Hospital, Sweden, between 1987 and 1995. The children's postnatal growth data, including serial measurements of height and weight (from which BMI was calculated), were obtained from health records. All children had a physical examination when they were aged between 5 and 13 years, at which height and weight were again recorded and used to calculate age- and sex-adjusted BMI z-scores.

Methods:

Subject-specific growth curves were fitted to the infant BMI data using penalized splines with random coefficients, and from these the location of the BMI peak for each participant was estimated. A multilevel modelling approach was used to assess the relationships between the BMI peak and BMI z-score in later childhood.

Results:

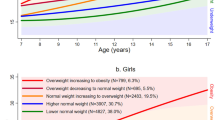

The BMI peak occurred, on average, slightly later in female children, with a higher BMI peak in male children. Considered separately, both age and BMI at BMI peak were positively associated with later BMI z-score. Considered jointly, both dimensions of BMI peak retained their positive associations.

Conclusions:

The growth trajectory associated with higher childhood BMI appears to include a later and/or higher BMI peak in infancy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organisation. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2004.

Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T . Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med 1993; 22: 167–177.

Dietz WH . Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics 1998; 101: 518–525.

Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD . Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes 1999; 23: S1–107.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempe M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E . Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1984; 39: 129–135.

Taylor RW, Grant AM, Goulding A, Williams SM . Early adiposity rebound: review of papers linking this to subsequent obesity in children and adults. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2005; 8: 607–612.

Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijen J, Roberts H, Law C . Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. Br Med J 2005; 331: 929.

Monteiro PO, Victora CG . Rapid growth in infancy and childhood and obesity in later life--a systematic review. Obes Rev 2005; 6: 143–154.

Ong KK, Loos RJ . Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: systematic reviews and hopeful suggestions. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95: 904–908.

Stettler N . Nature and strength of epidemiological evidence for origins of childhood and adulthood obesity in the first year of life. Int J Obes 2007; 31: 1035–1043.

Uppsala University. Uppsala family study http://www.pubcare.uu.se/family Viewed 16 october 2007.

Leon DA, Koupil I, Mann V, Tuvemo T, Lindmark G, Mohsen R et al. Fetal, developmental, and parental influences on childhood systolic blood pressure in 600 sib pairs: the Uppsala Family Study. Circulation 2005; 112: 3478–3485.

Karlberg J, Luo ZC, Albertsson-Wikland K . Body mass index reference values (mean and SD) for Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 2001; 90: 1427–1434.

Ruppert D, Wand MP, Carroll RJ . Semiparametric Regression. Cambridge University Press: New York, 2003.

Goldstein H . Multilevel Statistical Models. Hodder Arnold: London, 2003.

Laird NM, Ware JH . Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982; 38: 963–974.

Durbán M, Harezlak J, Wand MP, Carroll RJ . Simple fitting of subject-specific curves for longitudinal data. Stat Med 2005; 24: 1153–1167.

Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA . Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995; 73: 25–29.

Ong KK, Ahmed ML, Emmett PM, Preece MA, Dunger DB, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy Childhood Study Team. Association between postnatal catch-up growth and obesity in childhood: prospective cohort study. Br Med J 2000; 320: 967–971.

Fuentes RM, Notkola I-L, Shemeikka S, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A . Tracking of body mass index during childhood: a 15-year prospective population-based family study in eastern Finland. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 716–721.

Charney E, Goodman HC, McBride M, Lyon B, Pratt R . Childhood antecedents of adult obesity. Do chubby infants become obese adults? N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 6–9.

Robinson GK . That BLUP is a good thing: the estimation of random effects. Stat Sci 1991; 6: 15–51.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ilona Koupil, Torsten Tuvemo and Ann-Christine Synvanen for agreeing to providing access to these data and Rawya Mohsen for organizing the data. The original data collection was funded by the UK Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex

Annex

Consider initially the fitting of a growth curve for a single subject. Let yj be the (log transformed) BMI for this subject at age xj, j=1,…,n. Let k1, …, kK be a set of K distinct knots in the range of xj and define

Then the spline model of degree p with K knots at k1, …, kK is defined as

where β1, …, βp and u1, …, uK are to be estimated and  . As unconstrained fitting of u1, …, uK will result in a ‘wiggly’ fit14, a constraint such as ∑k=1Kuk2<C for some constant C may be imposed. The resulting model is referred to as a penalized spline model.

. As unconstrained fitting of u1, …, uK will result in a ‘wiggly’ fit14, a constraint such as ∑k=1Kuk2<C for some constant C may be imposed. The resulting model is referred to as a penalized spline model.

It can be shown14, using the principle of ‘best linear unbiased prediction’ (BLUP)22, that the penalized spline model (1) can be represented as a mixed model with  . The model can then be considered in the general linear mixed model form,

. The model can then be considered in the general linear mixed model form,

where

Subject-specific growth curves are obtained by the inclusion of subject-specific random (spline) parameters which model the deviation of a given individual's curve from the population average (spline) curve. Now consider all subjects in the data set so that yij is the (log transformed) BMI for subject i, i=1, …, m, at age xij, j=1, …, ni. Then the penalized spline model of degree p can be extended to give

where  , where ∑ is an unstructured (p+1) × (p+1) covariance matrix,

, where ∑ is an unstructured (p+1) × (p+1) covariance matrix,  , and all terms are independent of one another apart from ai0, …, aip for a given i. The present analysis used cubic penalized spline models, with both cubic population average curves and cubic subject-specific deviations from these (that is, (2) with p=3), to model BMI growth through infancy.

, and all terms are independent of one another apart from ai0, …, aip for a given i. The present analysis used cubic penalized spline models, with both cubic population average curves and cubic subject-specific deviations from these (that is, (2) with p=3), to model BMI growth through infancy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Silverwood, R., De Stavola, B., Cole, T. et al. BMI peak in infancy as a predictor for later BMI in the Uppsala Family Study. Int J Obes 33, 929–937 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.108

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.108

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Modelling individual infancy growth trajectories to predict excessive gain in BMI z-score: a comparison of growth measures in the ABCD and GECKO Drenthe cohorts

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Longitudinal association between the timing of adiposity peak and rebound and overweight at seven years of age

BMC Pediatrics (2022)

-

Infant feeding practices associated with adiposity peak and rebound in the EDEN mother–child cohort

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Socioeconomic disparities and infancy growth trajectory: a population-based and longitudinal study

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Maternal and infant prediction of the child BMI trajectories; studies across two generations of Northern Finland birth cohorts

International Journal of Obesity (2021)