Abstract

A recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (rAd5) vector-based vaccine for HIV-1 has recently failed in a phase 2b efficacy study in humans1,2. Consistent with these results, preclinical studies have demonstrated that rAd5 vectors expressing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Gag failed to reduce peak or setpoint viral loads after SIV challenge of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that lacked the protective MHC class I allele Mamu-A*01 (ref. 3). Here we show that an improved T-cell-based vaccine regimen using two serologically distinct adenovirus vectors afforded substantially improved protective efficacy in this challenge model. In particular, a heterologous rAd26 prime/rAd5 boost vaccine regimen expressing SIV Gag elicited cellular immune responses with augmented magnitude, breadth and polyfunctionality as compared with the homologous rAd5 regimen. After SIVMAC251 challenge, monkeys vaccinated with the rAd26/rAd5 regimen showed a 1.4 log reduction of peak and a 2.4 log reduction of setpoint viral loads as well as decreased AIDS-related mortality as compared with control animals. These data demonstrate that durable partial immune control of a pathogenic SIV challenge for more than 500 days can be achieved by a T-cell-based vaccine in Mamu-A*01-negative rhesus monkeys in the absence of a homologous Env antigen. These findings have important implications for the development of next-generation T-cell-based vaccine candidates for HIV-1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recombinant Ad5 vector-based vaccines expressing SIV Gag have been shown to afford dramatic control of viral replication after simian–human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)-89.6P challenge of rhesus monkeys4,5. However, rAd5-Gag vaccines have failed to reduce peak or setpoint viral loads after SIVMAC239 challenge of rhesus monkeys3, highlighting important differences in the stringencies of these challenge models. Heterologous DNA prime/rAd5 boost vaccine regimens have also failed to date to reduce setpoint viral loads after SIVMAC challenge of rhesus monkeys that lacked the protective MHC class I allele Mamu-A*01 (refs 3 and 6). The inability of vector-based vaccines to afford durable control of setpoint viral loads after SIVMAC challenge of Mamu-A*01-negative rhesus monkeys has led to substantial debate about the viability of the concept of developing T-cell-based vaccines for HIV-1.

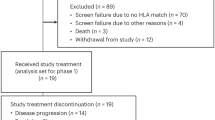

Pre-existing Ad5-specific neutralizing antibodies have been reported to reduce the immunogenicity of rAd5 vector-based vaccines in clinical trials7,8 and may also compromise their safety1. Rare serotype rAd vectors—such as rAd26 and rAd35 vectors9,10,11,12—have been developed as potential alternatives. Serologically distinct rAd vectors also allow the development of more potent heterologous rAd prime-boost vaccine regimens11. To investigate the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of such regimens, we immunized 22 Indian-origin rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that lacked the protective MHC class I alleles Mamu-A*01 (refs 13–15) and Mamu-B*17 (ref. 16) with the following heterologous or homologous rAd prime-boost regimens: (1) rAd26-Gag prime/rAd5-Gag boost (n = 6); (2) rAd35-Gag prime/rAd5-Gag boost (n = 6); (3) rAd5-Gag prime/rAd5-Gag boost (n = 4); and (4) sham controls (n = 6). One monkey each in groups 1, 3 and 4 expressed the protective Mamu-B*08 allele. Monkeys were primed at week 0 and boosted at week 24 with 1011 viral particles of each vector expressing SIVMAC239 Gag. At week 52, all animals received a high-dose intravenous (i.v.) challenge with 100 infectious doses of SIVMAC251 (ref. 6).

We monitored vaccine-elicited SIV Gag-specific cellular (Fig. 1a–c) and humoral (Fig. 1d) immune responses in these animals before challenge. After the priming immunization, IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) responses to pooled SIV Gag peptides were observed in all vaccinees. Monkeys primed with rAd26-Gag or rAd35-Gag were efficiently boosted by the heterologous rAd5-Gag vector to peak responses of 2,513 and 1,163 spot-forming cells per 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells, respectively, 2 weeks after the boost immunization (Fig. 1a; green bars). In contrast, monkeys primed with rAd5-Gag were only marginally boosted by a second injection of rAd5-Gag as a result of anti-vector immunity generated by the priming immunization11,17. Cell-depleted ELISPOT assays demonstrated that these responses were primarily CD8+ T lymphocyte responses, although lower levels of CD4+ T lymphocyte responses were also clearly observed (Fig. 1b). Epitope mapping was then performed by assessing ELISPOT responses against all 125 individual 15-amino-acid SIV Gag peptides after the boost immunization. The rAd26/rAd5 regimen elicited a mean of 8.6 detectable Gag epitopes per animal, whereas the rAd35/rAd5 regimen elicited a mean of 4.5 epitopes per animal and the rAd5/rAd5 regimen induced a mean of only 2.2 epitopes per animal (Fig. 1c). These data demonstrate that the heterologous rAd26/rAd5 regimen induced an 8.7-fold greater magnitude and a 3.9-fold increased breadth of Gag-specific cellular immune responses as compared with the homologous rAd5/rAd5 regimen.

Rhesus monkeys were primed at week 0 and boosted at week 24 with rAd26/rAd5, rAd35/rAd5 or rAd5/rAd5 regimens expressing SIV Gag. a, Gag-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were performed at weeks 0, 2, 24, 26 and 52 after immune priming. b, CD4+ (white bars) and CD8+ (black bars) T lymphocyte responses were evaluated at week 28 by CD8-depleted and CD4-depleted ELISPOT assays, respectively. SFC, spot-forming cells. c, The breadth of responses was determined by Gag epitope mapping at week 28. d, Gag-specific antibody responses were determined by ELISA at week 28. Mean responses with standard errors are shown (a–d). e, Functionality of Gag-specific CD8+ and CD4+ central memory (CM; CD28+CD95+) and effector memory (EM; CD28-CD95+) T lymphocyte responses were assessed by 8-colour ICS assays. Proportions of IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 responses are depicted individually and in all possible combinations for each cellular subpopulation. CD4+ EM responses after rAd5/rAd5 immunization were below the detection limit of the assay.

We next assessed the functionality of the vaccine-elicited, Gag-specific T lymphocyte responses by multiparameter flow cytometry18,19. Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assays were performed to assess IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 secretion in CD8+ and CD4+ central memory (CD28+CD95+) and effector memory (CD28-CD95+) T lymphocyte subpopulations20,21. Consistent with our previous findings11, we observed larger proportions of polyfunctional IFN-γ/TNF-α/IL-2-positive (black) and IL-2-positive (yellow) CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocyte responses in the animals that received the heterologous rAd26/rAd5 regimen as compared with the homologous rAd5/rAd5 regimen (Fig. 1e). In contrast, the rAd5/rAd5 regimen elicited primarily IFN-γ-positive (red) and IFN-γ/TNF-α-positive (blue) responses.

Six months after the boost immunization, all animals were challenged intravenously with SIVMAC251. Protective efficacy was evaluated by monitoring plasma SIV RNA levels (Fig. 2a, b), CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (Fig. 2c), and clinical disease progression and mortality (Fig. 2d) after challenge. Monkeys that received the rAd26/rAd5 regimen showed mean peak viral loads that were 1.43 logs lower than the mean peak viral loads in the control animals (Fig. 2a, b; P = 0.002, two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test with multiple comparison adjustments). More importantly, the rAd26/rAd5 vaccinated animals also demonstrated durable partial control of setpoint viral loads, as defined as the mean SIV RNA levels from day 112 to day 420 after challenge. In particular, the rAd26/rAd5-vaccinated monkeys maintained a 2.44 log reduction of setpoint viral loads as compared with the control animals (Fig. 2a, b; P = 0.01). If the three Mamu-B*08-positive animals are excluded from the analysis, then the rAd26/rAd5 regimen afforded a 2.66 log reduction of setpoint viral loads as compared with the control animals (P = 0.008; data not shown). As expected, the homologous rAd5/rAd5 regimen afforded no detectable control of setpoint viral loads, consistent with the previously reported failure of this regimen in this stringent SIV challenge model3.

Monkeys were challenged intravenously with SIVMAC251, and protective efficacy was monitored by SIV RNA levels (a, b), CD4+ T lymphocyte counts (c), and clinical disease progression and mortality (d) after challenge. Viral loads are depicted longitudinally for each group (a), and peak (day 14) and setpoint (day 112–420) viral loads are summarized for each group (b). Asterisks indicate mortality. Comparisons among groups were performed by two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum (a, b) and Fisher’s exact (d) tests.

Monkeys that received the rAd26/rAd5 regimen also demonstrated slower declines of CD4+ T lymphocyte counts as compared with the other groups (Fig. 2c). Moreover, the rAd26/rAd5 vaccine afforded a significant reduction of AIDS-related mortality as compared with the controls at day 500 after challenge (Fig. 2d; P = 0.03, Fisher’s exact test), whereas the rAd35/rAd5 and rAd5/rAd5 vaccines provided a trend towards a survival advantage. Necropsies showed that the causes of death were AIDS-defining illnesses, including Pneumocystis pneumonia, Cryptosporidium enteritis, cytomegalovirus pneumonia, SIV encephalitis and lymphoma.

We next evaluated the evolution of SIV-specific cellular (Fig. 3a, c, e) and humoral (Fig. 3b, d) immune responses in these animals after challenge. The rAd26/rAd5 vaccinees exhibited tenfold greater anamnestic Gag-specific ELISPOT responses as compared with the controls during both acute and chronic infection (Fig. 3a; black bars), suggesting the critical importance of these responses for immune control. In contrast, Pol-, Nef- and Env-specific cellular immune responses were either comparable or lower in magnitude in the rAd26/rAd5 vaccinees as compared with the other groups (Fig. 3a). The rAd26/rAd5 vaccinees thus showed less extensive diversification of cellular immune responses against these other SIV antigens, presumably reflecting the reduced viral replication in these animals. Phenotypic analysis of the Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses in the rAd26/rAd5 vaccinees demonstrated slightly higher expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α but 6.7-fold greater expression of IL-2 as compared with the rAd5/rAd5 vaccinees after challenge (Fig. 3c; green bars). These data suggest that not only quantitative but also qualitative differences among the vaccine regimens may have contributed to protective efficacy.

Cellular (a, c, e) and humoral (b, d) immune responses were assessed after challenge. IFN-γ ELISPOT assays (a) and ELISA and neutralizing antibody assays (b) were performed on days 0, 14, 28, 56 and 112 after challenge. NAb, neutralizing antibody; primary, primary isolate virus; TCLA, T-cell laboratory-adapted virus. Eight-colour ICS assays on day 28 (c), ADCVI assays at 1:100 serum dilution at the time points indicated (d), and Gag epitope mapping studies on day 28 (e) were also performed. Mean responses with standard errors are shown (a–e). f, Correlations between the breadth (left panels) or magnitude (right panels) of pre-challenge (top panels) or post-challenge (bottom panels) Gag-specific cellular immune responses and setpoint viral loads were evaluated by two-sided Spearman’s rank correlation tests. Monkeys immunized with rAd26/rAd5 (triangles), rAd35/rAd5 (diamonds), rAd5/rAd5 (squares) and sham (circles) vaccine regimens are depicted.

We assessed the breadth of Gag-specific cellular immune responses on day 28 after challenge by epitope mapping using 15-amino-acid SIV Gag peptides (Fig. 3e). The monkeys that received the rAd26/rAd5 regimen developed a mean of 16.1 (range 4–29) Gag epitope-specific responses after challenge. In contrast, the control animals developed <1 detectable Gag epitope-specific response after challenge. Notably, both the breadth and the magnitude of Gag-specific cellular immune responses elicited by vaccination (P = 0.0049 and P = 0.0025, respectively, Spearman’s rank-correlation tests) and recalled after challenge (P = 0.018 and P = 0.024, respectively) correlated with control of setpoint viral loads in these animals (Fig. 3f).

Humoral immune responses were evaluated by Gag- and Env-specific ELISAs as well as by luciferase-based pseudovirus neutralizing antibody assays using both laboratory-adapted and primary isolate SIVMAC251 viruses22 (Fig. 3b). The vaccinees developed more rapid kinetics of Gag-specific ELISA responses as compared with the controls after challenge, but no clear differences of Env-specific ELISA or neutralizing antibody responses were observed among groups. Compared with controls, the vaccinees also developed more rapid kinetics of antibody-dependent cell-mediated virus inhibition (ADCVI)23 on day 14 after challenge (Fig. 3d; P = 0.01), suggesting the potential functional relevance of nonclassical antibody responses in early SIV infection.

We next monitored CD4+ T lymphocyte dynamics in these animals after challenge. The monkeys that received the rAd26/rAd5 regimen had a relative preservation of central memory CD4+ T lymphocytes6 (Fig. 4a; black bars; P = 0.02, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test) as well as a more marked preservation of CCR5+ central memory CD4+ T lymphocytes24,25 (Fig. 4b; black bars; P = 0.002) as compared with the controls on day 14 after challenge. The rAd26/rAd5 vaccinees also showed reduced Ki67+ proliferation of CCR5+ central memory (Fig. 4c, d; P = 0.004) and effector memory (Fig. 4e, f; P = 0.004) CD4+ T lymphocytes as compared with the controls after challenge. In addition, on day 21 after challenge, monkeys that received the rAd26/rAd5 regimen maintained markedly higher levels of gastrointestinal CD4+ T lymphocytes in duodenal biopsies as compared with the controls, which showed extensive depletion of this lymphocyte population as expected26,27,28 (Fig. 4g; P = 0.02, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test).

Preservation of central memory (CM; CD28+CD95+) CD4+ T lymphocytes (a) and CCR5+ central memory CD4+ T lymphocytes (b) was assessed on days 0, 14, 28, 56 and 112 after challenge. Ki67 staining of central memory CD4+ (c), CCR5+ central memory CD4+ (d), effector memory (EM; CD28-CD95+) CD4+ (e), and CCR5+ effector memory CD4+ (f) T lymphocytes was also determined. Mean responses with standard errors are shown (a–f). g, Preservation of gastrointestinal CD4+ T lymphocytes was assessed in duodenal biopsies on day 21 after challenge. Comparisons were performed by two-sided Wilcoxon’s rank-sum tests.

Our data demonstrate that the heterologous rAd26/rAd5 regimen elicited improved magnitude, breadth and functionality of Gag-specific cellular immune responses as compared with the homologous rAd5/rAd5 regimen and afforded durable partial immune control of a homologous SIVMAC251 challenge in rhesus monkeys. To the best of our knowledge, vector-based vaccines have not previously been reported to reduce setpoint viral loads in the stringent system of SIVMAC challenge of Mamu-A*01-negative rhesus monkeys3,6, although a previous study has shown partial control of setpoint viral loads using a DNA/rAd5 regimen in the less stringent system of Mamu-A*01-positive rhesus monkeys29. In the present study, the breadth and magnitude of vaccine-elicited, Gag-specific cellular immune responses before challenge correlated with control of setpoint viral loads after challenge (Fig. 3f), suggesting the critical importance of Gag-specific T lymphocyte responses in controlling viral replication. Protective efficacy was also associated with improved functionality of Gag-specific T lymphocyte responses (Figs 1e and 3c), reduced diversification of responses against other SIV antigens after challenge (Fig. 3a), and preservation of CCR5+ central memory CD4+ T lymphocytes and gastrointestinal CD4+ T lymphocytes after challenge (Fig. 4b, g), although some of these parameters may reflect the result rather than the cause of the reduced viral replication.

It is important to highlight the fact that the vaccines used in the present study expressed only a single SIV Gag antigen and did not include a homologous Env immunogen. The observed protective efficacy was therefore presumably mediated by vaccine-elicited Gag-specific cellular immune responses, because it is unlikely that Gag-specific antibodies afforded substantial protection. Consistent with these data, a previous study reported that the breadth of Gag-specific cellular immune responses correlated with control of viral loads in chronically HIV-1-infected humans30. It remains possible, however, that other SIV antigens may also contribute to cellular immune protection if included in a multivalent vaccine. Future studies should address this possibility and evaluate the protective efficacy of optimal vaccine regimens against highly heterologous SIV challenges. The potential role of early ADCVI responses should also be explored, because ADCVI activity emerged more rapidly in the vaccinees as compared with the controls after challenge (Fig. 3d). These responses probably reflect immune preservation in the vaccinees rather than a direct result of vaccination, because ADCVI activity has been reported to be mediated by Env-specific antibodies23.

Despite current controversies about the use of rAd vector-based vaccines for HIV-1, our data have important implications for the development of next generation T-cell-based vaccines by the proof-of-concept demonstration that durable partial immune control of a pathogenic SIV challenge can be achieved in Mamu-A*01-negative rhesus monkeys. It remains unclear, however, whether the observed protection reflected the use of rAd26 vectors, the heterologous rAd prime-boost regimen, or both. Further studies will therefore be required to evaluate these possibilities and to determine the use of regimens consisting of two rare serotype rAd vectors. In conclusion, our findings suggest that T-cell-based vaccine regimens that elicit augmented magnitude, breadth and polyfunctionality of cellular immune responses as compared with the homologous rAd5 regimen may afford superior protective efficacy against HIV-1 and other pathogens.

Methods Summary

Animals, immunizations and challenge

Outbred rhesus monkeys that did not express the MHC class I alleles Mamu-A*01 and Mamu-B*17 were housed at New England Primate Research Center (NEPRC), Southborough, Massachusetts, USA. Immunizations involved 1011 viral particles of replication-incompetent, E1/E3-deleted rAd5, rAd35 or rAd26 vectors10,11,12 expressing SIVMAC239 Gag and were delivered as 1-ml injections intramuscularly in both quadriceps muscles at weeks 0 and 24. Sham controls received 1011 viral particles of empty vectors. At week 52, all animals received an i.v. inoculation of 100 infectious doses of SIVMAC251 as described6. SIV RNA levels were assessed after challenge on days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14 and 21, then weekly until day 42, biweekly until day 84, and monthly thereafter (Siemans Diagnostics). All animal studies were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC).

Cellular immune assays

SIV-specific cellular immune responses were assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays and multiparameter ICS assays essentially as described11,20,21. ELISPOT assays used pooled or individual SIV Gag peptides. Eight-colour ICS assays used pooled SIV Gag peptides and the following monoclonal antibodies (BD Pharmingen): anti-CD3-Alexa700 (SP34), anti-CD4-AmCyan (L200), anti-CD8-APC-Cy7 (SK1), anti-CD28-PerCP-Cy5.5 (L293), anti-CD95-PE (DX2), anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7 (B27), anti-IL-2-APC (MQ1-17H12) and anti-TNF-α-FITC (Mab11). Assessment of T lymphocyte dynamics used the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD3-Alexa700 (SP34), anti-CD4-AmCyan (L200), anti-CD8-APC-Cy7 (SK1), anti-CD28-PerCP-Cy5.5 (L293), anti-CD95-APC (DX2), anti-CCR5-PE (3A9), anti-HLA-DR-PE-Cy7 (L243) and anti-Ki67-FITC (B56). Gastrointestinal CD4+ T lymphocytes were evaluated after collagenase digestion of duodenal biopsies and percoll gradient purification.

Humoral immune assays

SIV-specific humoral immune responses were evaluated by SIV Gag- and SIV Env gp130-specific ELISAs, luciferase-based pseudovirus neutralization assays (using T-cell laboratory adapted and primary isolate viruses)22, and ADCVI assays23 essentially as described.

References

Fauci, A. S. The release of new data from the HVTN 502 (STEP) HIV vaccine study. National Institutes of Health (NIH) News, November 7. (2007)

Fauci, A. S. 25 years of HIV. Nature 453, 289–290 (2008)

Casimiro, D. R. et al. Attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection by prophylactic immunization with DNA and recombinant adenoviral vaccine vectors expressing Gag. J. Virol. 79, 15547–15555 (2005)

Shiver, J. W. et al. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature 415, 331–335 (2002)

Shiver, J. W. & Emini, E. A. Recent advances in the development of HIV-1 vaccines using replication-incompetent adenovirus vectors. Annu. Rev. Med. 55, 355–372 (2004)

Letvin, N. L. et al. Preserved CD4+ central memory T cells and survival in vaccinated SIV-challenged monkeys. Science 312, 1530–1533 (2006)

Catanzaro, A. T. et al. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 candidate vaccine delivered by a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus vector. J. Infect. Dis. 194, 1638–1649 (2006)

Priddy, F. H. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a replication-incompetent adenovirus type 5 HIV-1 clade B gag/pol/nef vaccine in healthy adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, 1769–1781 (2008)

Barouch, D. H. et al. Immunogenicity of recombinant adenovirus serotype 35 vaccine in the presence of pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity. J. Immunol. 172, 6290–6297 (2004)

Abbink, P. et al. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 81, 4654–4663 (2007)

Liu, J. et al. Magnitude and phenotype of cellular immune responses elicited by recombinant adenovirus vectors and heterologous prime-boost regimens in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 82, 4844–4852 (2008)

Vogels, R. et al. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J. Virol. 77, 8263–8271 (2003)

Mothe, B. R. et al. Expression of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule Mamu-A*01 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 77, 2736–2740 (2003)

Pal, R. et al. ALVAC-SIV-gag-pol-env-based vaccination and macaque major histocompatibility complex class I (A*01) delay simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac-induced immunodeficiency. J. Virol. 76, 292–302 (2002)

Zhang, Z. Q. et al. Mamu-A*01 allele-mediated attenuation of disease progression in simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 76, 12845–12854 (2002)

Yant, L. J. et al. The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B*17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 80, 5074–5077 (2006)

Santra, S. et al. Replication-defective adenovirus serotype 5 vectors elicit durable cellular and humoral immune responses in nonhuman primates. J. Virol. 79, 6516–6522 (2005)

Betts, M. R. et al. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107, 4781–4789 (2006)

Darrah, P. A. et al. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major . Nature Med. 13, 843–850 (2007)

Okoye, A. et al. Progressive CD4+ central memory T cell decline results in CD4+ effector memory insufficiency and overt disease in chronic SIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2171–2185 (2007)

Pitcher, C. J. et al. Development and homeostasis of T cell memory in rhesus macaque. J. Immunol. 168, 29–43 (2002)

Montefiori, D. Evaluating Neutralizing Antibodies Against HIV, SIV and SHIV in Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays (eds Coligan, J. E et al.) (Current Protocols in Immunology, John Wiley & Sons, 2004)

Forthal, D. N., Landucci, G. & Daar, E. S. Antibody from patients with acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection inhibits primary strains of HIV type 1 in the presence of natural-killer effector cells. J. Virol. 75, 6953–6961 (2001)

Veazey, R. S. et al. Dynamics of CCR5 expression by CD4+ T cells in lymphoid tissues during simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 74, 11001–11007 (2000)

Veazey, R. S. et al. Increased loss of CCR5+CD45RA-CD4+ T cells in CD8+ lymphocyte-depleted Simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 82, 5618–5630 (2008)

Veazey, R. S. et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280, 427–431 (1998)

Li, Q. et al. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434, 1148–1152 (2005)

Mattapallil, J. J. et al. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434, 1093–1097 (2005)

Wilson, N. A. et al. Vaccine-induced cellular immune responses reduce plasma viral concentrations after repeated low-dose challenge with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239. J. Virol. 80, 5875–5885 (2006)

Kiepiela, P. et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nature Med. 13, 46–53 (2007)

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Vogels, J. Custers, L. Holterman, A. Lemckert, F. Stephens, R. Dolin, N. Letvin, J. Schmitz, M. Lifton, K. Furr, L. Picker and M. Pensiero for generous advice, assistance and reagents. The SIV peptide pools were obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. We acknowledge support from NIH grants AI066305 (D.H.B.), AI066924 (D.H.B.), AI078526 (D.H.B.), AI030034 (D.C.M.) and RR000168.

Author Contributions J.L., K.L.O.’B., D.M.L., N.L.S., A.L.P. and A.M.R. planned, performed and analysed the cellular immunologic and virologic assays. R.T.C., L.E.G., M.S.S., G.L., D.N.F. and D.C.M. planned, performed and analysed the humoral immunologic assays. P.A., M.J.H., M.G.P. and J.G. prepared and quality controlled the vaccine vectors. A.C. and K.G.M. led the animal work. D.H.B. designed and led the study. All coauthors discussed the data and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., O’Brien, K., Lynch, D. et al. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature 457, 87–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07469

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07469

This article is cited by

-

Strategies for HIV-1 vaccines that induce broadly neutralizing antibodies

Nature Reviews Immunology (2023)

-

Immunogenic arenavirus vector SIV vaccine reduces setpoint viral load in SIV-challenged rhesus monkeys

npj Vaccines (2023)

-

Mathematical model of broadly reactive plasma cell production

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Adenovirus prime, Env protein boost vaccine protects against neutralization-resistant SIVsmE660 variants in rhesus monkeys

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Association of lymph-node antigens with lower Gag-specific central-memory and higher Env-specific effector-memory CD8+ T-cell frequencies in a macaque AIDS model

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.