Abstract

Paliperidone palmitate is a long-acting injectable antipsychotic agent. This 13-week, multicenter, randomized (1 : 1 : 1 : 1), double-blind, parallel-group study evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fixed 25, 50, and 100 milligram equivalent (mg equiv.) doses of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo administered as gluteal injections on days 1 and 8, then every 4 weeks (days 36 and 64) in 518 adult patients with schizophrenia. The intent-to-treat analysis set (N=514) was 67% men and 67% White, with a mean age of 41 years. All paliperidone palmitate dose groups showed significant improvement vs placebo in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score (primary efficacy measure; 25 and 50 mg equiv., p=0.02; 100 mg equiv., p<0.001), as well as Clinical Global Impression Severity scores (p⩽0.006) and PANSS negative and positive symptom Marder factor scores (p⩽0.04). The Personal and Social Performance scale showed no significant difference between treatment groups. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was similar between groups. Parkinsonism, the most frequently reported extrapyramidal symptom, was reported at similar rates for placebo (5%) and paliperidone palmitate (5–6% across doses). The mean body mass index and mean weight showed relatively small dose-related increases during paliperidone palmitate treatment. Investigator-evaluated injection-site pain, swelling, redness, and induration were similar across treatment groups; scores for patient-evaluated injection-site pain (visual analog scale) were similar across groups and diminished with time. All doses of once-monthly paliperidone palmitate were efficacious and generally tolerated, both locally and systemically. Paliperidone palmitate offers the potential to improve outcomes in adults with symptomatic schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Atypical antipsychotics are the mainstay of therapy for patients with schizophrenia. These agents are generally viewed as having efficacy at least equivalent to that of older neuroleptics, with a lower risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) and associated anhedonia and apathy, impaired cognition, and dysphoria (Lieberman et al, 2005; Tandon, 2002; Tandon and Jibson, 2002). Although considered a significant advancement over older drugs, atypical antipsychotics still have limited efficacy in many patients (Stroup et al, 2006), particularly with respect to negative and cognitive symptoms. Tolerability, in some patients, remains a concern (Lieberman et al, 2005).

Adherence to therapy is also an important challenge in the management of schizophrenia. The adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment, as well as restrictive dosing regimens (such as the requirement to take drugs with food or multiple times a day), are a few of several factors that may compromise oral antipsychotic treatment adherence (Cooper et al, 2007; Gianfrancesco et al, 2006; Keith and Kane, 2003). General dissatisfaction with oral antipsychotic therapy was underscored by results from the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) study, which indicated that although 10–18% of patients discontinued initial treatment because of adverse events, ∼30% discontinued for reasons unrelated to tolerability, safety, or efficacy (Lieberman et al, 2005). Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics offer the potential to improve adherence, and to provide additional benefits, such as improving long-term treatment outcomes (Kane et al, 2003). The LAI formulation of risperidone, which was the first injectable atypical antipsychotic, was developed in response to the need for new and better-tolerated LAI antipsychotics and to decrease relapse (Taylor et al, 2004).

Paliperidone, the active metabolite of the atypical antipsychotic risperidone, is one of the most recent oral atypical antipsychotics to become available for the treatment of schizophrenia. As an extended-release oral formulation, it was effective and tolerated in controlled clinical trials (Davidson et al, 2007; Kane et al, 2007; Kramer et al, 2007; Marder et al, 2007). Recently, an LAI intramuscular formulation of this compound, paliperidone palmitate, became the first once-monthly atypical antipsychotic approved in the United States for schizophrenia treatment. Paliperidone palmitate has important advantages over presently available medications, including its efficacy and tolerability in both acute and maintenance treatment, dosing options in both gluteal and deltoid muscles, no need for oral supplementation, and ready-to-use syringes that do not require reconstitution or refrigeration. A phase 2 trial of two doses of paliperidone palmitate (50 and 100 milligram equivalents (mg equiv.)) suggested that it is effective and tolerated by patients with schizophrenia (Kramer et al, 2010). The present confirmatory phase 3 trial, designed and sponsored by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, assessed the safety and efficacy of three fixed doses of paliperidone palmitate, injected into the gluteal muscle, in a larger sample of patients with schizophrenia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Paliperidone Palmitate Doses

Doses of paliperidone palmitate can be expressed either in terms of milligram equivalents of the pharmacologically active fraction, paliperidone, or in milligrams of paliperidone palmitate. Thus, the doses expressed as ‘paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv.’ equate to 39, 78, and 156 mg, respectively, of paliperidone palmitate.

Study Design

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-response study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three fixed doses (25, 50, and 100 mg equiv.) of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo. Patients were enrolled at 38 centers in 5 countries: the United States (19 centers), South Africa (2 centers), Bulgaria, Romania, and Russia (17 centers total in these 3 European countries). The study included a screening period of up to 7 days and a 13-week double-blind treatment period. Hospitalization was required for all patients from days 1 through 8 of treatment. An Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board reviewed the study protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Clinical Practices and applicable regulatory requirements. Patients or their legal representatives provided written informed consent before participating.

Patients

Eligible patients were men or women (if not pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant) who met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) for at least 1 year before screening. Patients had a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score at screening and baseline of 70–120 (inclusive) and a body mass index (BMI)>15.0 kg/m2, and were able and willing to meet or perform study requirements. Major exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Treatments

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 ratio to receive matched placebo injections (Intralipid, 2007), or intramuscular fixed doses of paliperidone palmitate (25, 50, or 100 mg equiv.), without oral supplementation. Initial doses were administered on days 1 and 8, then every 4 weeks (days 36 and 64) of the double-blind treatment period. All doses of study medication were injected into the gluteal muscle on the left or right side in an alternating manner. Patients were followed up for 28 days after the last injection on day 64.

Patients without documented previous exposure to risperidone or paliperidone underwent an oral tolerability test (day −7 to day −1). Only patients who tolerated the oral test medication could continue into the study.

Data Analysis

The intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set included all patients who were randomized, received ⩾1 dose of double-blind study medication, and had both the baseline and ⩾1 postbaseline efficacy assessment. The safety analysis set included all patients who were randomized and received ⩾1 dose of double-blind study medication. The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline to end point (last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach: day 92 or the last postbaseline assessment in the double-blind period) in PANSS total score. Secondary efficacy variables were changes from baseline to end point in Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) and Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scales (Morosini et al, 2000). Other efficacy variables included PANSS subscales, PANSS Marder factor scores, and treatment responder rate (defined as patients with a ⩾30% decrease from baseline in PANSS total score at end point).

Safety evaluations included reports of adverse events, EPS rating scales (Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale: AIMS; Guy, W (1976)), Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS; Barnes (1989)), and Simpson Angus Scale (SAS; Simpson and Angus (1970)), clinical laboratory tests, 12-lead electrocardiograms, physical examination findings, investigators’ evaluation of the injection site, and patients’ evaluations of pain at the injection site.

All efficacy analyses used the ITT analysis set. For the change in PANSS total score at end point, least-squares adjusted means were calculated for each active treatment group vs placebo, using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment and country as factors and baseline score as a continuous covariate. The closed testing procedure using Dunnett’s test was applied to adjust for multiple testing of paliperidone palmitate doses vs placebo. Exploration of the treatment-by-country interaction was prespecified at a 0.10 significance level. A mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was performed as a sensitivity analysis, using observed case data for the change from baseline in PANSS total score. A similar ANCOVA model as described above was used for the change at end point in CGI-S (on ranked changes), PSP, PANSS negative, positive, and general psychopathology subscales, and PANSS Marder factor scores. The Bonferroni–Holm step-down testing procedure was applied to the analysis of the change in CGI-S (ranked changes) and PSP scales to adjust for multiple comparisons. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons for other efficacy variables. Differences between treatment groups in the percentages of responders were evaluated using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, controlling for country. A Kaplan–Meier plot of the estimated time to discontinuation due to lack of efficacy was presented by the treatment group to assess the consistency with other efficacy findings.

Safety analyses were based on the safety analysis set and summarized using descriptive statistics. Treatment-emergent adverse events were summarized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class and preferred term.

Adjusting for multiple comparisons of the three paliperidone palmitate dose groups with placebo (two-sided α-level 0.05), 110 patients in each group were required to detect a treatment difference of 10 points with a power of 90%. Adjusted for a rate of 8% of patients without either baseline or postbaseline efficacy assessments, 120 patients were required per treatment group.

RESULTS

Patients

Demographics and patient characteristics were well balanced across treatment groups, with 514 patients (99% of those randomized) included in the ITT analysis set (Table 2).

Of the 518 randomized patients, 263 (51%) patients completed the 13-week double-blind period. The safety analysis set included >99% of all randomized patients (n=517). Reasons for and rates of early withdrawal showed no apparent differences across groups, with the exception of withdrawals due to lack of efficacy. More patients in the placebo group (35%) discontinued because of lack of efficacy than in the paliperidone palmitate treatment groups, with the paliperidone 100 mg equiv. group having the lowest rate of discontinuation because of lack of efficacy (16 vs 24% for both the 25- and 50-mg groups) (Figure 1). Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to discontinuation because of lack of efficacy are shown (Figure 2).

Study design. The doses expressed as paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv. equate to 39, 78, and 156 mg, respectively, of paliperidone palmitate. One patient assigned to the paliperidone palmitate 25 mg equiv. group was excluded by the medical monitor on the day of randomization, due to hypotension, and hence did not receive any double-blind medication.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to withdrawal due to lack of efficacy (intent-to-treat analysis set). The doses expressed as paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv. equate to 39, 78, and 156 mg, respectively, of paliperidone palmitate.

Efficacy

Primary outcome: PANSS total score

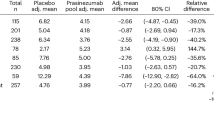

On the basis of the LOCF ANCOVA analysis at end point, PANSS total scores for all paliperidone palmitate groups improved significantly vs placebo (multiplicity adjusted, 25 mg equiv., p=0.015; 50 mg equiv., p=0.017; and 100 mg equiv., p<0.001) (Figure 3). The MMRM analysis corroborated these findings as all three doses of paliperidone palmitate resulted in significant improvement vs placebo overall (p⩽0.019), as well as on day 92 (p⩽0.021). None of the pairwise comparisons between active treatment groups were significant. The primary efficacy LOCF analysis showed a statistically significant treatment-by-country interaction (p=0.02). Patients enrolled at sites outside the United States had greater improvements in PANSS total scores than did those from US sites. US sites contributed the largest percentage of patients (55%) to the ITT analysis set, followed by Russia (31%), Bulgaria (7%), Romania (4%), and South Africa (3%). Demographic and baseline characteristics were examined to determine whether any imbalance across treatment groups and countries occurred. Subsequently, a notable disparity was detected in the distribution of baseline BMI across countries, but not across treatment groups: 74% of US patients were obese (BMI ⩾30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI ⩾25 and <30 kg/m2), whereas 42% of Romanian, 41% of Russian, 35% of Bulgarian, and 23% of South African patients were either obese or overweight. The mean BMI at baseline in the US was 30.2 kg/m2 (range: 17–60 kg/m2) compared with 24.2 kg/m2 (range: 16–38 kg/m2) in the non-US regions. An exploratory ANCOVA, on the change in PANSS total score, with treatment, country, BMI, and treatment-by-BMI interaction as factors, and baseline PANSS total score as a covariate was performed. The interaction of BMI on the treatment effect was suggestive of a differential treatment effect by BMI category, as it approached the statistical significance level of 0.10 (p=0.14). Hence, the heterogeneous treatment effect across BMI categories was considered a key contributor to the treatment-by-country interaction, given the disparity in BMI distribution across countries.

Onset of effect: least-squares mean change in PANSS total score over time (intent-to-treat analysis set). Mean (SD) changes in PANSS total scores from baseline to end point were −13.6 (21.45) for the 25-mg group, −13.2 (20.14) for the 50-mg group, and −16.1 (20.36) for the 100-mg equiv. group, vs −7.0 (20.07) for placebo. The mean (SD) values reported below the graph are absolute means and not adjusted for the covariates. The doses expressed as paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv. equate to 39, 78, and 156 mg, respectively, of paliperidone palmitate. ^All unadjusted p-values <0.05 as early as day 36, for all three doses of paliperidone palmitate.

Secondary and other efficacy outcomes

CGI-S scores, and PANSS positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscale scores, and PANSS positive symptoms and negative symptoms Marder factor scores significantly improved vs placebo for all paliperidone groups, whereas PSP scores did not (Table 3).

On the basis of the 30% response criterion, significantly more patients in the paliperidone palmitate 25 mg equiv. (45.7%; p=0.015) and 100 mg equiv. (51.9%; p<0.001) groups were treatment responders than those in the placebo group (31.2%). The paliperidone palmitate 50 mg equiv. group (37.5%) did not differ statistically (p=0.27 vs placebo).

Safety

Adverse events

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events occurred at similar rates among the paliperidone palmitate (66–75%) and placebo (72%) groups. The incidences of adverse events occurring in ⩾5% of patients in any group were generally similar for paliperidone palmitate and placebo, except that weight increase (4% paliperidone palmitate overall vs 0% placebo) and somnolence (4% paliperidone palmitate overall vs 1% placebo) occurred more frequently (with ⩾3% difference) with paliperidone palmitate treatment (Figure 4).

Treatment-emergent adverse events experienced by ⩾5% of patients in any treatment group. The doses expressed as paliperidone palmitate 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv. equate to 39, 78, and 156 mg, respectively, of paliperidone palmitate.

The incidence of serious treatment-emergent adverse events was higher in the placebo group (18%) than in any of the paliperidone palmitate groups (8–14%). Two patients died during the study. One patient in the paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv. group committed suicide on day 58, 22 days after the third injection of study medication and 1 patient in the placebo group died as a result of pancreatic carcinoma on day 66, after receiving all 4 doses of study medication. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to discontinuation was lower in the paliperidone palmitate 50 mg equiv. group (2%) than in any of the other treatment groups (5–6%). The adverse events that most often led to discontinuation were schizophrenia worsening and agitation.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

The incidence of treatment-emergent EPS events was low. Parkinsonism was the most frequent category and was reported at a similar rate in the placebo (5%) and overall paliperidone palmitate groups (6%). None of the events in paliperidone palmitate-treated patients were severe or serious, and no patient discontinued treatment as a result. The percentage of patients receiving anti-EPS medications decreased from before the double-blind period to the end of the study in all treatment groups: from 31 to 6% for placebo, from 31 to 7% for paliperidone palmitate 25 mg equiv., from 38 to 4% for paliperidone palmitate 50 mg equiv., and from 27 to 6% for paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv. There were no clinically relevant differences between the paliperidone palmitate groups and placebo in changes in BARS, SAS, or AIMS scores and generally no statistically significant differences (Table 4).

Laboratory values and vital signs

Increases in prolactin levels occurred with greater frequency in paliperidone palmitate-treated patients and were dose related. The mean change (SD) from baseline to end point in men vs women was: placebo, −2.1 (1.7) vs −8.8 (7.4); 25 mg equiv., 4.0 (2.4) vs 9.3 (5.5), 50 mg equiv., 6.8 (2.2) vs 35.1 (6.7); and 100 mg equiv., 10.4 (2.2) vs 43.6 (7.7) ng/ml. The incidence of spontaneously reported potentially prolactin-related treatment-emergent adverse events was low: 1–2% of paliperidone palmitate-treated patients and 1% of placebo patients. These events included erectile dysfunction (1% for placebo and 1% for paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv.), galactorrhea (1% for paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv.), decreased libido (1% for placebo), and sexual dysfunction (1% for paliperidone palmitate 50 mg equiv. and 2% for paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv.).

Mean body weight and mean BMI increased in a dose-related manner in the paliperidone palmitate groups, compared with mean decreases for placebo (Table 5). Except for prolactin, there were no clinically relevant mean changes from baseline to any time point for laboratory analytes, including renal function, liver function, serum lipids, or glucose, and none from baseline to end point in vital signs. No patient had a maximum linear-derived corrected QT interval (QTcLD) value >480 ms or a maximal change in QTcLD >60 ms at any time point during the study. The mean (SD) changes from baseline to end point in QTcLD were 0.7 (13.3) ms for placebo, 0.2 (12.1) ms for paliperidone palmitate 25 mg equiv., 1.7 (14.0) ms for paliperidone palmitate 50 mg equiv., and 0.2 (13.3) m for paliperidone palmitate 100 mg equiv.

Injection-site tolerability

Patient evaluations of injection-site pain, as measured by a visual analog scale (0 mm (no pain) to 100 mm (maximum pain)), were similar across treatment groups, and pain scores decreased with time. The day 1 and day 92 injection-site mean pain scores for placebo-treated patients were 8.3 and 1.2 mm, respectively. For patients treated with paliperidone palmitate, the day 1 and day 92 injection-site mean pain scores were 6.9 and 0.7 mm (25 mg equiv. dose group); 6.6 and 3.5 mm (50 mg equiv. dose group); and 5.8 and 1.4 mm (100 mg equiv. dose group), respectively.

Investigators reported injection-site pain during the study as absent (86–100%), mild (0–12%), or moderate to severe (0–2%) for paliperidone palmitate-treated patients. They reported similar scores for placebo-treated patients: absent (87–100%), mild (0–13%), or moderate to severe (0–2%). Investigator evaluations also showed that occurrences of redness, induration, or swelling were infrequent, generally mild, decreased over time, and similar in incidence for the paliperidone palmitate and placebo groups.

DISCUSSION

LAI preparations offer important options for treatment of chronic diseases and are particularly important for enhancing adherence, which may in turn benefit treatment outcomes and quality of life (Bhanji et al, 2004; Love, 2002; Marinis et al, 2007; Nasrallah et al, 2004). Adherence to treatment is probably a major reason for the lower risk for relapse with LAI formulations vs oral antipsychotic therapy. With LAI formulations, there is greater interaction between the patient and the health-care provider. The provider knows when a patient misses an injection and has the opportunity to intervene because the sustained medication delivery provides a time window to follow-up with the patient. There are several other advantages of LAI formulations. If a relapse does occur, the health-care practitioner can determine whether it is the result of poor patient adherence or due to the disease process (Kane et al, 2003). LAIs also provide relatively stable plasma levels of drug once steady state is achieved and generally offer improved tolerability over oral formulations. Despite these advantages, LAIs remain underused (Nasrallah, 2007).

This randomized, placebo-controlled, 13-week double-blind study showed that paliperidone palmitate (25, 50, and 100 mg equiv.), a long-acting atypical injectable antipsychotic, significantly improved the PANSS total score compared with placebo, as well as CGI-S, PANSS Marder factor scores, and responder rates when administered once monthly, without oral supplementation, into the gluteal muscle in patients with symptomatic schizophrenia. The PSP scale, a validated scale that assesses personal and social functioning (Nasrallah et al, 2008; Morosini et al, 2000; Patrick et al, 2009) did not show a significant treatment difference, perhaps due to the high placebo response observed in this study.

The incidence of treatment-emergent EPS-related adverse events was low in paliperidone palmitate-treated patients. There were no clinically important increases in lipids or glucose levels seen in this 13-week study. However, mean body weight and mean BMI increased in a dose-related manner in paliperidone palmitate-treated patients. Dose-related increases in prolactin levels also occurred in paliperidone palmitate-treated patients. The incidence of spontaneously reported potentially prolactin-related adverse events was low (⩽2%), although relying on spontaneous reports may result in underreporting of actual cases of sexual dysfunction.

Prolongation of the QT intervals remains a concern with the use of antipsychotics (Taylor, 2003). In this study, there was no evidence of clinically significant QTc prolongation with paliperidone palmitate at doses up to 100 mg equiv. Change from baseline in QTcLD values was similar across all treatment groups.

Investigator evaluations of injection-site pain, swelling, redness, and induration, as well as patient evaluations of injection-site pain during this study, suggest that paliperidone palmitate is well tolerated locally, with minimal pain or injection-site reactions.

These results are generally consistent with those from other recent studies of paliperidone palmitate for both the acute and maintenance treatment of patients with schizophrenia (Gopal et al, 2010; Hough et al, 2008, 2009; Kramer et al, 2010), as well as for the oral formulation, paliperidone (Davidson et al, 2007; Kane et al, 2007; Kramer et al, 2007; Luthringer et al, 2007; Marder et al, 2007). Although in this study, paliperidone palmitate was administered gluteally, it may be administered in the deltoid muscle as well (Hough et al, 2009). This offers an additional advantage in supporting patient preference for injection site.

In this study, a once-monthly dosing regimen with paliperidone palmitate doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg equiv. produced clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in efficacy measures in patients with symptomatic schizophrenia. The tolerability profile of paliperidone palmitate may offer additional advantages in helping to ensure treatment adherence.

References

Barnes TR (1989). A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154: 672–676.

Bhanji NH, Chouinard G, Margolese HC (2004). A review of compliance, depot intramuscular antipsychotics and the new long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic risperidone in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 87–92.

Cooper D, Moisan J, Gregoire JP (2007). Adherence to atypical antipsychotic treatment among newly treated patients: a population-based study in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 68: 818–825.

Davidson M, Emsley R, Kramer M, Ford L, Pan G, Lim P et al (2007). Efficacy, safety and early response of paliperidone extended-release tablets (paliperidone ER): results of a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 93: 117–130.

Gianfrancesco FD, Rajagopalan K, Sajatovic M, Wang RH (2006). Treatment adherence among patients with schizophrenia treated with atypical and typical antipsychotics. Psychiatry Res 144: 177–189.

Gopal S, Hough DW, Xu H, Lull JM, Gassmann-Mayer C, Remmerie BM et al (2010). Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in adult patients with acutely symptomatic schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Intl Clin Psychopharm (e-pub ahead of print 10 April 2010).

Guy W (1976). AIMS. In: Guy W (ed). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare: Rockville, MD. pp 534–537.

Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M (2008). Paliperidone palmitate, an injectable antipsychotic, in prevention of symptom recurrence in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized,double-blind, placebo-controlled study. In Biol Psych. Society of Biological Psychiatry (SOBP), Washington, DC USA, pp 285S–286S.

Hough D, Lindenmayer JP, Gopal S, Melkote R, Lim P, Herben V et al (2009). Safety and tolerability of deltoid and gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33: 1022–1031.

Intralipid (2007). (prescribing information) Fresenius Kabi AB Uppsala, Sweden.

Kane J, Canas F, Kramer M, Ford L, Gassmann-Mayer C, Lim P et al (2007). Treatment of schizophrenia with paliperidone extended-release tablets: a 6-week placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res 90: 147–161.

Kane JM, Leucht S, Carpenter D, Docherty JP (2003). The expert consensus guideline series. Optimizing pharmacologic treatment of psychotic disorders. Introduction: methods, commentary, and summary. J Clin Psychiatry 64 (Suppl 12): 5–19.

Keith SJ, Kane JM (2003). Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 1308–1315.

Kramer M, Litman R, Hough D, Lane R, Lim P, Liu Y et al (2010). Paliperidone palmitate, a potential long-acting treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study. Intl J Neuropsychopharm 13: 635–647.

Kramer M, Simpson G, Maciulis V, Kushner S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P et al (2007). Paliperidone extended release tablets for prevention of symptom recurrence in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharm 27: 6–14.

Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO et al (2005). Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 353: 1209–1223.

Love RC (2002). Strategies for increasing treatment compliance: the role of long-acting antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm 59 (22 Suppl 8): S10–S15.

Luthringer R, Staner L, Noel N, Muzet M, Gassmann-Mayer C, Talluri K et al (2007). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study evaluating the effect of paliperidone extended-release tablets on sleep architecture in patients with schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 22: 299–308.

Marder SR, Kramer M, Ford L, Eerdekens E, Lim P, Eerdekens M et al (2007). Efficacy and safety of paliperidone extended-release tablets: results of a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 62: 1363–1370.

Marinis TD, Saleem PT, Glue P, Arnoldussen WJ, Teijeiro R, Lex A et al (2007). Switching to long-acting injectable risperidone is beneficial with regard to clinical outcomes, regardless of previous conventional medication in patients with schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry 40: 257–263.

Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R (2000). Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101: 323–329.

Nasrallah HA, Duchesne I, Mehnert A, Janagap C, Eerdekens M (2004). Health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 531–536.

Nasrallah HA (2007). The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand 115: 260–267.

Nasrallah H, Morosini P, Gagnon DD (2008). Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with stable schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 161: 213–224.

Patrick DL, Burns T, Morosini P, Rothman M, Gagnon DD, Wild D et al (2009). Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the clinician-rated Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with acute symptoms of schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin 25: 325–338.

Simpson GM, Angus JW (1970). A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212: 11–19.

Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA et al (2006). Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 163: 611–622.

Tandon R (2002). Safety and tolerability: how do newer generation ‘atypical’ antipsychotics compare? Psychiatr Q 73: 297–311.

Tandon R, Jibson MD (2002). Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic treatment: scope of problem and impact on outcome. Ann Clin Psychiatry 14: 123–129.

Taylor DM (2003). Antipsychotics and QT prolongation. Acta Psychiatr Scand 107: 85–95.

Taylor DM, Young CL, Mace S, Patel MX (2004). Early clinical experience with risperidone long-acting injection: a prospective, 6-month follow-up of 100 patients. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 1076–1083.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Rhodes, PhD, and the editorial staff of Clinical Connexion for writing and editorial support during the development of this paper, and Wendy P Battisti, PhD (Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC) for additional writing, editorial, and scientific support. We also thank the following investigators for their participation in this study: Bulgaria: Grozeva, Penka, MD, Jivkov, Lubomir, MD, and Sayan, Loris, MD; Romania: Gabos Grecu, Losif, MD, Grigoriu, Alexandru Loan, MD, Popescu, Ioana, MD, and Teodorescu, Radu, MD; Russia: Andreev, Boris, MD, PhD, Ivanov, Mikhail, MD, PhD, Morozova, Margarita, MD, PhD, Panteleyeva, Galina, MD, PhD, Popov, Mikhail, MD, PhD, Reshetko, Olga, MD, PhD, Smulevich, Anatoly, MD, PhD, Suchkov, Yuri, MD, and Yakhin, Kausar, MD, PhD; South Africa: Ramjee, Paresh, MD and Selemani, S, MD; United States of America: Alam, Mohammed, MD, Askins, Howard, MD, Booker, J Gary, MD, Brenner, Ronald, MD, Buckley, Peter F, MD, Cuervo, Mario, MD, Dempsey, G Michael, MD, DeSilva, Himasiri, MD, Isacescu, Valentin, MD, Knapp, Richard D, DO, Larson, Gunnar L, MD, CCRI, Litman, Robert E, MD, Lowy, Adam F, MD, Marks, David M, MD, Nasrallah, Henry, MD, Riesenberg, Robert A, MD, Sack, David, MD, Shanbhag, Suhas, MD, Shiwach, Rajinder, MD, Valencerina, Madeleine M, MD, and Vijapura, Amit, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This study was funded by Johnson & Johnson Research & Development, LLC, Raritan, NJ, who was responsible for study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Dr Nasrallah was an investigator in this study and over the past 3 years has received research grant support from Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development to conduct FDA studies and investigator-initiated studies, and has received consultation fees and speaker honoraria as well. He has also received grants, or participated in speakers bureaus or advisory boards for the following pharmaceutical companies: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Forest, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Shire, and Novartis. Over the past 3 years, Drs Gopal, Gassmann-Mayer, Quiroz, Lim, and Yuen have been employed by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, Raritan, NJ, and have stock or stock options in the company; Dr Eerdekens has been employed by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Division of Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium and holds stock and stock options in the company. Dr Hough was employed by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, for all but the time from April 2008 to April 2009, during which he worked as an independent consultant. Dr Quiroz was employed by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, from 2005 to June 2009 (which includes the period of this study) and has since been employed by Hoffman- LaRoche Pharma Development and Exploratory Neuroscience, Nutley, NJ.

Author Contributions: HAN was a principal investigator and the coordinating investigator for this study and contributed to data collection and interpretation and literature analysis. SG, JAQ, ME, EY, and DH contributed to study design and data interpretation. DH and SG wrote the protocol. CG-M and PL contributed to study design, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to writing and reviewing this report and approved the final paper.

Registration Information: This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov corresponding to NCT# 00101634.

Additional information

Previous presentations: Data from this study were presented at the American Psychiatric Association 161st Annual Meeting, 3–8 May 2008, and the 60th Institute of Psychiatric Services Annual Meeting, 2–5 October 2008.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nasrallah, H., Gopal, S., Gassmann-Mayer, C. et al. A Controlled, Evidence-Based Trial of Paliperidone Palmitate, A Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotic, in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol 35, 2072–2082 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.79

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.79

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Calibrated meta-analysis to estimate the efficacy of mental health treatments in target populations: an application to paliperidone trials for treatment of schizophrenia

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2023)

-

Paliperidone palmitate vs. paliperidone extended-release for the acute treatment of adults with schizophrenia: a systematic review and pairwise and network meta-analysis

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Benefits and harms of Risperidone and Paliperidone for treatment of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis involving individual participant data and clinical study reports

BMC Medicine (2021)

-

Antipsychotics for negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia: dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled acute phase trials

npj Schizophrenia (2021)

-

Evidence-Based Expert Consensus Regarding Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics for Schizophrenia from the Taiwanese Society of Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology (TSBPN)

CNS Drugs (2021)