Key Points

-

Childhood leukaemia is the most common paediatric cancer in developed societies.

-

The disease is biologically heterogeneous and no single or exclusive causal mechanism is likely.

-

The natural history of paediatric leukaemia usually involves pre-natal initiation of pre-leukaemic clones (frequently by chromosome translocation) followed by postnatal promotion, secondary mutation and overt disease. Latency after initiation can be very variable (a few months to 15 years).

-

Ionizing radiation is an accepted cause of leukaemia but not a significant cause. Non-ionizing radiation (for example, electromagnetic field radiation) seems to be a very weak or negligible cause.

-

Large, case–control epidemiology studies are required that incorporate biological subtypes of disease and inherited alleles associated with susceptibility. These studies also need to be driven by plausible biological hypotheses.

-

Two infection-based hypotheses have been proposed and assessed: Kinlen's 'population-mixing' hypothesis and Greaves' 'delayed-infection' hypothesis.

-

The body of epidemiological evidence now available is consistent with the view that many childhood leukaemias arise as a consequence of an abnormal immune response to common infection(s), but the mechanisms remain to be determined.

Abstract

Childhood leukaemia is the principal subtype of paediatric cancer and, despite success in treatment, its causes remain enigmatic. A plethora of candidate environmental exposures have been proposed, but most lack a biological rationale or consistent epidemiological evidence. Although there might not be a single or exclusive cause, an abnormal immune response to common infection(s) has emerged as a plausible aetiological mechanism.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Incidence of Childhood Cancer (eds Parkin, D. M. et al.) (IARC Scientific Publications, Lyon, 1988).

International Incidence of Childhood Cancer Volume II (eds Parkin, D. M. et al.) (IARC Scientific Publications No. 144, Lyon, 1998).

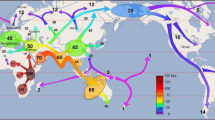

Greaves, M. F. et al. Geographical distribution of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia subtypes: second report of the collaborative group study. Leukemia 7, 27–34 (1993).

Pinkel, D. Lessons from 20 years of curative therapy of childhood acute leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 65, 148–153 (1992).

Kersey, J. H. Fifty years of studies of the biology and therapy of childhood leukemia. Blood 90, 4243–4251 (1997).

Pui, C. -H., Relling, M. V. & Downing, J. R. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1535–1548 (2004). Comprehensive, recent summary of current understanding of the biological and clinical heterogeneity of childhood leukaemia.

Neglia, J. P. et al. Second neoplasms after acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N. Engl. J. Med. 325, 1330–1336 (1991).

Hudson, M. in Childhood Leukemias (ed. Pui, C.-H.) 463–481 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999).

Childhood Leukemias (ed. Pui, C.-H.) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999).

Nesse, R. M. & Williams, G. C. Evolution and Healing. The New Science of Darwinian Medicine (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995).

Greaves, M. Cancer. The Evolutionary Legacy (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000).

Stearns, S. C. & Ebert, D. Evolution in health and disease. Q. Rev. Biol. 76, 417–432 (2001).

Linet, M. S. & Devesa, S. S. in Leukemia (eds Henderson, E. S., Lister, T. A. & Greaves, M. F.) 131–151 (Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002).

Ross, J. A., Davies, S. M., Potter, J. D. & Robison, L. L. Epidemiology of childhood leukemia, with a focus on infants. Epidemiol. Rev. 16, 243–272 (1994).

Preston, D. L. et al. Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part III: leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, 1950–1987. Radiat. Res. 137 (Suppl.), S68–S97 (1994).

Doll, R. & Wakeford, R. Risk of childhood cancer from fetal irradiation. Br. J. Radiol. 70, 130–139 (1997).

Brenner, D. J. et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13761–13766 (2003). Critical analysis of the contentious issue of risks from low-dose ionizing radiation.

Wakeford, R. The cancer epidemiology of radiation. Oncogene 23, 6404–6428 (2004).

Wakeford, R. & Tawn, E. J. The risk to health from low doses of ionising radiation. Nuclear Future 1, 107–114 (2005).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. The United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study of exposure to domestic sources of ionising radiation. 2: γ radiation. Br. J. Cancer 86, 1727–1731 (2002).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. The United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study of exposure to domestic sources of ionising radiation. I: radon gas. Br. J. Cancer 86, 1721–1726 (2002).

Ahlbom, A. et al. A pooled analysis of magnetic fields and childhood leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 83, 692–698 (2000).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. Exposure to power-frequency magnetic fields and the risk of childhood cancer. Lancet 354, 1925–1931 (1999).

Coghill, R. W., Steward, J. & Philips, A. Extra low frequency electric and magnetic fields in the bedplace of children diagnosed with leukaemia: a case–control study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 5, 153–158 (1996).

Fews, A. P., Henshaw, D. L., Wilding, R. J. & Keitch, P. A. Corona ions from powerlines and increased exposure to pollutant aerosols. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 75, 1523–1531 (1999).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. Exposure to power frequency electric fields and the risk of childhood cancer in the UK. Br. J. Cancer 87, 1257–1266 (2002).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. Childhood cancer and residential proximity to power lines. Br. J. Cancer 83, 1573–1580 (2000).

Greaves, M. Molecular genetics, natural history and the demise of childhood leukaemia. Eur. J. Cancer 35, 173–185 (1999).

Taylor, G. M. & Birch, J. M. in Leukemia (eds Henderson, E. S., Lister, T. A. & Greaves, M. F.) 210–245 (WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1996).

Savitz, D. A. & Andrews, K. W. Review of epidemiologic evidence on benzene and lymphatic and hematopoietic cancers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 31, 287–295 (1997).

Smith, M. A., McCaffrey, R. P. & Karp, J. E. The secondary leukemias: challenges and research directions. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 88, 407–418 (1996).

UK Childhood Cancer Study Investigators. The United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study: objectives, materials and methods. Br. J. Cancer 82, 1073–1102 (2000). Detailed description of the design of the largest case–control epidemiological study of possible causes of childhood cancer.

Greaves, M. F. Aetiology of acute leukaemia. Lancet 349, 344–349 (1997).

Ross, J. A., Potter, J. D. & Robison, L. L. Infant leukemia, topoisomerase II inhibitors, and the MLL gene. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 86, 1678–1680 (1994).

Alexander, F. E. et al. Transplacental chemical exposure and risk of infant leukaemia with MLL gene fusion. Cancer Res. 61, 2542–2546 (2001).

Strick, R., Strissel, P. L., Borgers, S., Smith, S. L. & Rowley, J. D. Dietary bioflavonoids induce cleavage in the MLL gene and may contribute to infant leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4790–4795 (2000).

Wiemels, J. L. et al. A lack of a functional NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase allele is selectively associated with pediatric leukemias that have MLL fusions. Cancer Res. 59, 4095–4099 (1999).

Smith, M. T. et al. Low NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase activity is associated with increased risk of leukemia with MLL translocations in infants and children. Blood 100, 4590–4593 (2002).

Draper, G. J., Kroll, M. E. & Stiller, C. A. Childhood cancer. Cancer Surv. 19–20, 493–517 (1994).

Greaves, M. F. & Alexander, F. E. An infectious etiology for common acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood? Leukemia 7, 349–360 (1993).

Ford, A. M. et al. In utero rearrangements in the trithorax-related oncogene in infant leukaemias. Nature 363, 358–360 (1993).

Ford, A. M. et al. Fetal origins of the TEL–AML1 fusion gene in identical twins with leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4584–4588 (1998).

Gale, K. B. et al. Backtracking leukemia to birth: identification of clonotypic gene fusion sequences in neonatal blood spots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13950–13954 (1997).

Wiemels, J. L. et al. Prenatal origin of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children. Lancet 354, 1499–1503 (1999).

Mori, H. et al. Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8242–8247 (2002). Provides unambiguous evidence that pre-leukaemic clones with chromosomal translocations are generated prenatally at approximately 100-times the rate of overt leukaemia.

Greaves, M. F., Maia, A. T., Wiemels, J. L. & Ford, A. M. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood 102, 2321–2333 (2003). Details the insights into the timing and development of childhood leukaemia — these insights were derived from molecular studies of concordant leukaemia in identical twins.

Greaves, M. F. & Wiemels, J. Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nature Rev. Cancer 3, 639–649 (2003).

Tsuzuki, S., Seto, M., Greaves, M. & Enver, T. Modelling first-hit functions of the t(12;21) TEL–AML1 translocation in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8443–8448 (2004). In vivo mimicry in mice of the pre-leukaemic status initiated by TEL–AML1.

Fischer, M. et al. Defining the oncogenic function of the TEL–AML1 (ETV6–RUNX1) fusion protein in a mouse model. Oncogene 24, 7579–7591 (2005).

Morrow, M., Horton, S., Kioussis, D., Brady, H. J. M. & Williams, O. TEL–AML1 promotes development of specific hematopoietic lineages consistent with preleukemic activity. Blood 103, 3890–3896 (2004). In vivo mimicry in murine cells of the pre-leukaemic status initiated by TEL–AML1.

Bernardin, F. et al. TEL–AML1, expressed from t(12;21) in human acute lymphocytic leukemia, induces acute leukemia in mice. Cancer Res. 62, 3904–3908 (2002).

Yuan, Y. et al. AML1–ETO expression is directly involved in the development of acute myeloid leukemia in the presence of additional mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10398–10403 (2001).

Cooke, J. V. The incidence of acute leukemia in children. JAMA 119, 547–550 (1942).

Poynton, F. J., Thursfield, H. & Paterson, D. The severe blood diseases of childhood: a series of observations from the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street. Br. J. Child. Dis. XIX, 128–144 (1922).

Kellett, C. E. Acute myeloid leukaemia in one of identical twins. Arch. Dis. Childhood 12, 239–252 (1937).

Ward, G. The infective theory of acute leukaemia. Br. J. Child. Dis. 14, 10–20 (1917).

Human T-Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma Virus. The Family of Human T-Lymphotropic Retroviruses: Their Role in Malignancies and Association With AIDS (eds Gallo, R. C., Essex, M. E. & Gross, L.) (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, 1984).

Schulz, T. F. & Neil, J. C. in Leukemia (eds Henderson, E. S., Lister, T. A. & Greaves, M. F.) 200–225 (Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002).

Committee on Medical Aspects of Radiation in the Environment (COMARE). First Report. The Implications of the New Data on the Releases From Sellafield in the 1950s for the Conclusions of the Report on the Investigation of the Possible Increased Incidence of Cancer in West Cumbria (Department of Health, 1986).

Gardner, M. J. et al. Results of case–control study of leukaemia and lymphoma among young people near Sellafield nuclear plant in West Cumbria. Br. Med. J. 300, 423–429 (1990).

Kinlen, L. Evidence for an infective cause of childhood leukaemia: comparison of a Scottish New Town with nuclear reprocessing sites in Britain. Lancet ii, 1323–1327 (1988). First description of the 'population-mixing' hypothesis for childhood leukaemia.

Greaves, M. F. Speculations on the cause of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2, 120–125 (1988). First description of the 'delayed-infection' hypothesis for childhood leukaemia.

Wills-Karp, M., Santeliz, J. & Karp, C. L. The germless theory of allergic disease: revisiting the hygiene hypothesis. Nature Rev. Immunol. 1, 69–75 (2001).

Dunne, D. W. & Cooke, A. A worm's eye view of the immune system: consequences for evolution of human autoimmune disease. Nature Rev. Immunol. 5, 420–426 (2005).

Strachan, D. P. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the 'hygiene hypothesis'. Thorax 55, S2–S10 (2000).

Yazdanbakhsh, M., Kremsner, P. G. & van Ree, R. Allergy, parasites and the hygiene hypothesis. Science 296, 490–494 (2002).

Kolb, H. & Elliott, R. B. Increasing incidence of IDDM a consequence of improved hygiene? Diabetologia 37, 729–731 (1994).

Alvord, E. C. Jr et al. The multiple causes of multiple sclerosis: The importance of age of infections in childhood. J. Child Neurol. 2, 313–321 (1987).

Gutensohn, N. & Cole, P. Childhood social environment and Hodgkin's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 304, 135–140 (1981).

Backett, E. M. Social patterns of antibody to poliovirus. Lancet i, 779–783 (1957).

Little, J. Epidemiology of Childhood Cancer (IARC Scientific Publications, Lyon, 1999).

McNally, R. J. Q. & Eden, T. O. B. An infectious aetiology for childhood acute leukaemia: a review of the evidence. Br. J. Haematol. 127, 243–263 (2004). Most comprehensive, recent audit of epidemiological data on possible causal mechanisms involving infection in childhood leukaemia.

Heath, C. W. Jr & Hasterlik, R. J. Leukemia among children in a suburban community. Am. J. Med. 34, 796–812 (1963). First description of a time–space cluster for childhood leukaemia.

Steinmaus, C., Lu, M., Todd, R. L. & Smith, A. H. Probability estimates for the unique childhood leukemia cluster in Fallon, Nevada, and risks near other U. S. military aviation facilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 766–771 (2004).

Alexander, F. E. Space-time clustering of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: indirect evidence for a transmissible agents. Br. J. Cancer 65, 589–592 (1992).

Petridou, E. et al. Space–time clustering of childhood leukaemia in Greece: evidence supporting a viral aetiology. Br. J. Cancer 73, 1278–1283 (1996).

Kinlen, L. J. Epidemiological evidence for an infective basis in childhood leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 71, 1–5 (1995).

Kinlen, L. J., Clarke, K. & Hudson, C. Evidence from population mixing in British New Towns 1946–85 on an infective basis for childhood leukaemia. Lancet 336, 577–582 (1990).

Kinlen, L. J. & John, S. M. Wartime evacuation of children and mortality from childhood leukaemia in England and Wales in 1945–49. Br. Med. J. 309, 1197–1202 (1994).

Kinlen, L. J. & Hudson, C. Childhood leukaemia and polio-myelitis in relation to military encampments in England and Wales in the period of national military service, 1950–63. Br. Med. J. 303, 1357–1362 (1991).

Kinlen, L. J. & Balkwill, A. Infective cause of childhood leukaemia and wartime population mixing in Orkney and Shetland, UK. Lancet 357, 858 (2001).

Dickinson, H. O. & Parker, L. Quantifying the effect of population mixing on childhood leukaemia risk: the Seascale cluster. Br. J. Cancer 81, 144–151 (1999).

Alexander, F. E. et al. Clustering of childhood leukaemia in Hong Kong: association with the childhood peak and common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and with population mixing. Br. J. Cancer 75, 457–463 (1997).

Kinlen, L. & Doll, R. Population mixing and childhood leukaemia: Fallon and other US clusters. Br. J. Cancer 91, 1–3 (2004).

Smith, M. Considerations on a possible viral etiology for B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood. J. Immunother. 20, 89–100 (1997).

Istre, G. R., Conner, J. S., Broome, C. V., Hightower, A. & Hopkins, R. S. Risk factors for primary invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease: increased risk from day care attendance and school-aged household members. J. Pediatr. 106, 190–195 (1985).

Adler, S. P. Molecular epidemiology of cytomegalovirus: viral transmission among children attending a day care center, their parents, and caretakers. J. Pediatr. 112, 366–372 (1988).

Fleming, D. W., Cochi, S. L., Hightower, A. W. & Broome, C. V. Childhood upper respiratory tract infections: to what degree is incidence affected by day-care attendance? Pediatr. 79, 55–60 (1987).

Goodman, R. A., Osterholm, M. T., Granoff, D. M. & Pickering, L. K. Infectious diseases and child day care. Pediatr. 74, 134–139 (1984).

Krämer, U., Heinrich, J., Wjst, M. & Wichmann, H. -E. Age of entry to day nursery and allergy in later childhood. Lancet 353, 450–454 (1999).

McKinney, P. A. et al. Early social mixing and childhood Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a case–control study in Yorkshire, UK. Diabet. Med. 17, 236–242 (2000).

Gilham, C. et al. Day care in infancy and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: findings from a UK case–control study. Br. Med. J. 330, 1294–1297 (2005). Largest study to date providing evidence that social contacts in infancy can reduce risk of childhood ALL.

Ma, X. et al. Daycare attendance and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 86, 1419–1424 (2002). Provides evidence that increasing levels of social contact in early life (through day-care) proportionally reduce the risk of childhood ALL.

Ma, X. et al. Ethnic difference in daycare attendance, early infections, and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 14, 1928–1934 (2005).

Krynska, B. et al. Detection of human neurotropic JC virus DNA sequence and expression of the viral oncogenic protein in pediatric medulloblastomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11519–11524 (1999).

McNally, R. J. Q. et al. An infectious aetiology for childhood brain tumours? Evidence from space–time clustering and seasonality analyses. Br. J. Cancer 86, 1070–1077 (2002).

Petridou, E. et al. Age of exposure to infections and risk of childhood leukaemia. Br. Med. J. 307, 774 (1993).

Infante-Rivard, C., Fortier, I. & Olsen, E. Markers of infection, breast-feeding and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 83, 1559–1564 (2000).

Perrillat, F. et al. Day-care, early common infections and childhood acute leukaemia: a multicentre French case–control study. Br. J. Cancer 86, 1064–1069 (2002).

Jourdan-Da Silva, N. et al. Infectious diseases in the first year of life, perinatal characteristics and childhood acute leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 90, 139–145 (2004).

Neglia, J. P. et al. Patterns of infection and day care utilization and risk factors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Br. J. Cancer 82, 234–240 (2000).

Dockerty, J. D., Draper, G., Vincent, T., Rowan, S. D. & Bunch, K. J. Case–control study of parental age, parity and socioeconomic level in relation to childhood cancers. Int. J. Epidemiol. 30, 1428–1437 (2001).

Ma, X. et al. Vaccination history and risk of childhood leukaemia. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34, 1100–1109 (2005).

Groves, F. D., Sinha, D., Kayhty, H., Goedert, J. J. & Levine, P. H. Haemophilus influenzae type b serology in childhood leukaemia: a case–control study. Br. J. Cancer 85, 337–340 (2001).

Auvinen, A., Hakulinen, T. & Groves, F. Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccination and risk of childhood leukaemia in a vaccine trial in Finland. Br. J. Cancer 83, 956–958 (2000).

Stene, L. C. & Nafstad, P. Relation between occurrence of type 1 diabetes and asthma. Lancet 357, 607–608 (2001).

Feltbower, R. G., McKinney, P. A., Greaves, M. F., Parslow, R. C. & Bodansky, H. J. International parallels in leukaemia and diabetes epidemiology. Arch. Dis. Childhood 89, 54–56 (2004).

Schüz, J., Morgan, G., Bö hler, E., Kaatsch, P. & Michaelis, J. Atopic disease and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 105, 255–260 (2003).

Wen, W. et al. Allergic disorders and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (United States). Cancer Causes Control 11, 303–307 (2000).

MacKenzie, J. et al. Infectious agents and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: no evidence of molecular footprints of a transforming virus. Haematologica (in the press).

Balkwill, F., Charles, K. A. & Mantovani, A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7, 211–217 (2005).

Ford, A. M., Cardus, P. & Greaves, M. F. Modelling molecular consequences of leukaemia initiation by TEL–AML1 fusion. Blood 104, 566 (2004).

Hiebert, S. W. et al. The t(12;21) translocation converts AML-1B from an activator to a repressor of transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1349–1355 (1996).

Guidez, F. et al. Recruitment of the nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR by the TEL moiety of the childhood leukemia-associated TEL–AML1 oncoprotein. Blood 96, 2557–2561 (2000).

Cookson, W. The alliance of genes and environment in asthma and allergy. Nature 402 (Suppl.), B5–B11 (1999).

Trinchieri, G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nature Rev. Immunol. 3, 133–146 (2003).

Morahan, G. et al. Association of IL12B promoter polymorphism with severity of atopic and non-atopic asthma in children. Lancet 360, 455–459 (2002).

Morahan, G. et al. Linkage disequilibrium of a type 1 diabetes susceptibility locus with a regulatory IL12B allele. Nature Genet. 27, 218–221 (2001).

Le Souëf, P. N., Goldblatt, J. & Lynch, N. R. Evolutionary adaptation of inflammatory immune responses in human beings. Lancet 356, 242–244 (2000).

Greaves, M. F. Evolution, immune response, and cancer. Lancet 356, 1034 (2000).

Taylor, G. M. et al. Genetic susceptibility to childhood common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is associated with polymorphic peptide-binding pocket profiles in HLA-DPB1*0201. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1585–1597 (2002).

Dorak, M. T. et al. Unravelling an HLA-DR association in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 94, 694–700 (1999).

Sturniolo, T. et al. Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nature Biotechnol. 17, 555–561 (1999).

Breatnach, F., Chessells, J. M. & Greaves, M. F. The aplastic presentation of childhood leukaemia: a feature of common-ALL. Br. J. Haematol. 49, 387–393 (1981).

Hasle, H. et al. Transient pancytopenia preceding acute lymphoblastic leukemia (pre-ALL). Leukemia 9, 605–608 (1995).

Heegaard, E. D., Madsen, H. O. & Schmiegelow, K. Transient pancytopenia preceding acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (pre-ALL) precipitated by parvovirus B19. Br. J. Haematol. 114, 810–813 (2001).

Liang, R., Cheng, G., Wat, M. S., Ha, S. Y. & Chan, L. C. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia presenting with relapsing hypoplastic anaemia: progression of the same abnormal clone. Br. J. Haematol. 83, 340–342 (1993).

Ishikawa, K. et al. Detection of neoplastic clone in the hypoplastic and recovery phases preceding acute lymphoblastic leukemia by in vitro amplification of rearranged T-cell receptor δ chain gene. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 17, 270–275 (1995).

Infectious Causes of Cancer (ed. Goedert, J. J.) (Humana Press, New Jersey, 2000).

Isaacson, P. G. & Du, M. -Q. MALT lymphoma: from morphology to molecules. Nature Rev. Cancer 4, 644–653 (2004).

Wotherspoon, A. C. et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 342, 575–577 (1993).

Hitzler, J. K. & Zipursky, A. Origins of leukaemia in children with Down syndrome. Nature Rev. Cancer 5, 11–20 (2005).

Dockerty, J. D. et al. Infections, vaccinations and the risk of childhood leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 80, 1483–1489 (1999).

Chan, L. C. et al. Is the timing of exposure to infection a major determinant of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in Hong Kong? Paediatr. Perinatal Epidemiol. 16, 154–165 (2002).

MacKenzie, J., Perry, J., Ford, A. M., Jarrett, R. F. & Greaves, M. JC and BK virus sequences are not detectable in leukaemic samples from children with common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 81, 898–899 (1999).

Smith, M. A. et al. Investigation of leukemia cells from children with common acute lymphoblastic leukemia for genomic sequences of the primate polyomaviruses JC virus, BK virus, and simian virus 40. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 33, 441–443 (1999).

Priftakis, P. et al. Human polyomavirus DNA is not detected in Guthrie cards (dried blood spots) from children who developed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 40, 219–223 (2003).

Isa, A., Priftakis, P., Broliden, K. & Gustafsson, B. Human parvovirus B19 DNA is not detected in Guthrie cards from children who have developed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 42, 357–360 (2004).

Bogdanovic, G., Jernberg, A. G., Priftakis, P., Grillner, L. & Gustafsson, B. Human herpes virus 6 or Epstein–Barr virus were not detected in Guthrie cards from children who later developed leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 91, 913–915 (2004).

MacKenzie, J. et al. Screening for herpesvirus genomes in common acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 15, 415–421 (2001).

Bender, A. P. et al. No involvement of bovine leukemia virus in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Res. 48, 2919–2922 (1988).

Shiramizu, B., Yu, Q., Hu, N., Yanagihara, R. & Nerurkar, V. R. Investigation of TT virus in the etiology of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 19, 543–551 (2002).

Hoffjan, S. J. et al. Gene–environment interaction effects on the development of immune responses in the 1st year of life. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 696–704 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This review is dedicated to the memory of Professor Sir Richard Doll who chaired the UKCCS Management Committee and was a powerful advocate for epidemiological studies on childhood leukaemia. The author's research is supported by a specialist programme grant from the Leukaemia Research Fund and by The Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

National Cancer Institute

Glossary

- Non-homologous end-joining repair

-

Predominant, cellular mechanism for the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks; error-prone as no template sequence is used.

- Time–space clustering

-

Increased incidence of cases in one place in a defined time period. This can occur by chance. A vivid illustration of this is the finding of statistically significant clusters in the United Kingdom in proximity to 'military sites' that turn out to be derelict medieval forts (R. Cartwright, personal communication).

- Representative difference analysis

-

This method assesses whether there are any sequences in the DNA of patients' leukaemic cells that are not of endogenous origin and is based on subtracting leukaemic ('tester') DNA from constitutive or normal, non-leukaemic ('driver') DNA of the same individual.

- T-helper (TH)1 and TH2 response

-

A TH1 cell-mediated immune response is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ, interleukin-1β and tumour-necrosis factor. It promotes cellular immune responses against intracellular infections and malignancy. A TH2 response involves production of cytokines, such as interleukin-4, that stimulate antibody production. TH2 cytokines promote secretory immune responses of mucosal surfaces to extracellular pathogens, and allergic reactions.

- Aplasia

-

Defective production of red and white blood cells by the bone marrow.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greaves, M. Infection, immune responses and the aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 193–203 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1816

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1816

This article is cited by

-

Research on knowledge construction and analysis of pesticide exposure to children based on bibliometrics

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Maternal antibiotics exposure during pregnancy and the risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis

European Journal of Pediatrics (2022)

-

Infectious triggers and novel therapeutic opportunities in childhood B cell leukaemia

Nature Reviews Immunology (2021)

-

Family history of early onset acute lymphoblastic leukemia is suggesting genetic associations

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Seasonal variations in childhood leukaemia incidence in France, 1990–2014

Cancer Causes & Control (2021)