Abstract

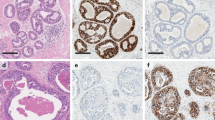

Invasive, genetically abnormal carcinoma progenitor cells have been propagated from human and mouse breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesions, providing new insights into breast cancer progression. The survival of DCIS cells in the hypoxic, nutrient-deprived intraductal niche could promote genetic instability and the derepression of the invasive phenotype. Understanding potential survival mechanisms, such as autophagy, that might be functioning in DCIS lesions provides strategies for arresting invasion at the pre-malignant stage. A new, open trial of neoadjuvant therapy for patients with DCIS constitutes a model for testing investigational agents that target malignant progenitor cells in the intraductal niche.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allegra, C. et al. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ. NIH Consens. State Sci. Statements 26, 1–27 (2009).

Castro, N. P. et al. Evidence that molecular changes in cells occur before morphological alterations during the progression of breast ductal carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 10, R87 (2008).

Damonte, P. et al. Mammary carcinoma behavior is programmed in the precancer stem cell. Breast Cancer Res. 10, R50 (2008).

Espina, V. et al. Malignant precursor cells pre-exist in human breast DCIS and require autophagy for survival. PLoS ONE 5, e10240 (2010).

Ma, X. J., Dahiya, S., Richardson, E., Erlander, M. & Sgroi, D. C. Gene expression profiling of the tumor microenvironment during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 11, R7 (2009).

Ma, X. J. et al. Gene expression profiles of human breast cancer progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5974–5979 (2003).

Namba, R. et al. Heterogeneity of mammary lesions represent molecular differences. BMC Cancer 6, 275 (2006).

Sgroi, D. C. Preinvasive breast cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 5, 193–221 (2010).

Fordyce, C. et al. DNA damage drives an activin a-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in premalignant cells and lesions. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 3, 190–201 (2010).

Gauthier, M. L. et al. Abrogated response to cellular stress identifies DCIS associated with subsequent tumor events and defines basal-like breast tumors. Cancer Cell 12, 479–491 (2007).

Mathew, R., Karantza-Wadsworth, V. & White, E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer 7, 961–967 (2007).

Sendoel, A., Kohler, I., Fellmann, C., Lowe, S. W. & Hengartner, M. O. HIF-1 antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis through a secreted neuronal tyrosinase. Nature 465, 577–583 (2010).

Boecker, W. Preneoplasia of the Breast (Elsevier GmbH, Munich, 2006).

Gudjonsson, T., Adriance, M. C., Sternlicht, M. D., Petersen, O. W. & Bissell, M. J. Myoepithelial cells: their origin and function in breast morphogenesis and neoplasia. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 10, 261–272 (2005).

Tavassoli, F. in Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs (eds Tavassoli, F. & Devilee, P.) 63–73 (IARC-Press, Lyon, 2003).

Claus, E. B. et al. Pathobiologic findings in DCIS of the breast: morphologic features, angiogenesis, HER-2/neu and hormone receptors. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 70, 303–316 (2001).

Hu, M. et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell 13, 394–406 (2008).

Page, D. L., Dupont, W. D., Rogers, L. W. & Landenberger, M. Intraductal carcinoma of the breast: follow-up after biopsy only. Cancer 49, 751–758 (1982).

Betsill, W. L., Rosen, P. P., Lieberman, P. H. & Robbins, G. F. Intraductal carcinoma. Long-term follow-up after treatment by biopsy alone. JAMA 239, 1863–1867 (1978).

Collins, L. C. et al. Outcome of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ untreated after diagnostic biopsy: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer 103, 1778–1784 (2005).

Fisher, B. et al. Prevention of invasive breast cancer in women with ductal carcinoma in situ: an update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Semin. Oncol. 28, 400–418 (2001).

Berman, H. K., Gauthier, M. L. & Tlsty, T. D. Premalignant breast neoplasia: a paradigm of interlesional and intralesional molecular heterogeneity and its biological and clinical ramifications. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 3, 579–587 (2010).

Lagios, M. D. Heterogeneity of duct carcinoma in situ (DCIS): relationship of grade and subtype analysis to local recurrence and risk of invasive transformation. Cancer Lett. 90, 97–102 (1995).

Bussolati, G., Bongiovanni, M., Cassoni, P. & Sapino, A. Assessment of necrosis and hypoxia in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: basis for a new classification. Virchows Arch. 437, 360–364 (2000).

Bindra, R. S. & Glazer, P. M. Genetic instability and the tumor microenvironment: towards the concept of microenvironment-induced mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 569, 75–85 (2005).

Kongara, S. et al. Autophagy regulates keratin 8 homeostasis in mammary epithelial cells and in breast tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 873–884 (2010).

Li, C. Y. et al. Persistent genetic instability in cancer cells induced by non-DNA-damaging stress exposures. Cancer Res. 61, 428–432 (2001).

Mathew, R., Karantza-Wadsworth, V. & White, E. Assessing metabolic stress and autophagy status in epithelial tumors. Meth. Enzymol. 453, 53–81 (2009).

Nelson, D. A. et al. Hypoxia and defective apoptosis drive genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 18, 2095–2107 (2004).

Vakkila, J. & Lotze, M. T. Inflammation and necrosis promote tumour growth. Nature Rev. Immunol. 4, 641–648 (2004).

Paweletz, C. P. et al. Reverse phase protein microarrays which capture disease progression show activation of pro-survival pathways at the cancer invasion front. Oncogene 20, 1981–1989 (2001).

Klionsky, D. J. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175 (2008).

Levine, B. & Ranganathan, R. Autophagy: Snapshot of the network. Nature 466, 38–40 (2010).

Lyng, H., Sundfor, K., Trope, C. & Rofstad, E. K. Oxygen tension and vascular density in human cervix carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 74, 1559–1563 (1996).

Vaupel, P., Kallinowski, F. & Okunieff, P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 49, 6449–6465 (1989).

Boyer, M. J., Barnard, M., Hedley, D. W. & Tannock, I. F. Regulation of intracellular pH in subpopulations of cells derived from spheroids and solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 68, 890–897 (1993).

Mayr, N. A., Staples, J. J., Robinson, R. A., Vanmetre, J. E. & Hussey, D. H. Morphometric studies in intraductal breast carcinoma using computerized image analysis. Cancer 67, 2805–2812 (1991).

Pinder, S. E. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): pathological features, differential diagnosis, prognostic factors and specimen evaluation. Mod. Pathol. 23 (Suppl. 2), S8–S13 (2010).

Mihaylova, V. T. et al. Decreased expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene Mlh1 under hypoxic stress in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3265–3273 (2003).

Young, S. D., Marshall, R. S. & Hill, R. P. Hypoxia induces DNA overreplication and enhances metastatic potential of murine tumor cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 9533–9537 (1988).

Rotin, D., Robinson, B. & Tannock, I. F. Influence of hypoxia and an acidic environment on the metabolism and viability of cultured cells: potential implications for cell death in tumors. Cancer Res. 46, 2821–2826 (1986).

Tannock, I. F. & Kopelyan, I. Influence of glucose concentration on growth and formation of necrosis in spheroids derived from a human bladder cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 46, 3105–3110 (1986).

Primeau, A. J., Rendon, A., Hedley, D., Lilge, L. & Tannock, I. F. The distribution of the anticancer drug Doxorubicin in relation to blood vessels in solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 8782–8788 (2005).

Jin, S., DiPaola, R. S., Mathew, R. & White, E. Metabolic catastrophe as a means to cancer cell death. J. Cell Sci. 120, 379–383 (2007).

Tang, D. et al. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 190, 881–892 (2010).

Shimizu, S. et al. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nature Cell Biol. 6, 1221–1228 (2004).

Hockel, M. & Vaupel, P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 93, 266–276 (2001).

Yu, F., White, S. B., Zhao, Q. & Lee, F. S. HIF-1α binding to VHL is regulated by stimulus-sensitive proline hydroxylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9630–9635 (2001).

Semenza, G. L. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nature Rev. Cancer 3, 721–732 (2003).

Cuvier, C., Jang, A. & Hill, R. P. Exposure to hypoxia, glucose starvation and acidosis: effect on invasive capacity of murine tumor cells and correlation with cathepsin (L + B) secretion. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 15, 19–25 (1997).

Young, S. D. & Hill, R. P. Effects of reoxygenation on cells from hypoxic regions of solid tumors: anticancer drug sensitivity and metastatic potential. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 82, 371–380 (1990).

McDermott, K. M. et al. p16(INK4a) prevents centrosome dysfunction and genomic instability in primary cells. PLoS Biol. 4, e51 (2006).

Bracken, A. P. et al. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 22, 5323–5335 (2003).

Reynolds, P. A. et al. Tumor suppressor p16INK14A regulates polycomb-mediated DNA hypermethylation in human mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24790–24802 (2006).

Ding, L., Erdmann, C., Chinnaiyan, A. M., Merajver, S. D. & Kleer, C. G. Identification of EZH2 as a molecular marker for a precancerous state in morphologically normal breast tissues. Cancer Res. 66, 4095–4099 (2006).

Kleer, C. G. et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11606–11611 (2003).

Crawford, Y. G. et al. Histologically normal human mammary epithelia with silenced p16(INK4a) overexpress COX-2, promoting a premalignant program. Cancer Cell 5, 263–273 (2004).

Kerlikowske, K. et al. Biomarker expression and risk of subsequent tumors after initial ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 102, 627–637 (2010).

Simpson, P. T., Reis-Filho, J. S., Gale, T. & Lakhani, S. R. Molecular evolution of breast cancer. J. Pathol. 205, 248–254 (2005).

Stingl, J. & Caldas, C. Molecular heterogeneity of breast carcinomas and the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Nature Rev. Cancer 7, 791–799 (2007).

Burkhardt, L. et al. Gene amplification in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 123, 757–765 (2010).

Li, H. et al. PIK3CA mutations mostly begin to develop in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 88, 150–155 (2010).

Bocker, W. et al. Common adult stem cells in the human breast give rise to glandular and myoepithelial cell lineages: a new cell biological concept. Lab. Invest. 82, 737–746 (2002).

Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J. & Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3983–3988 (2003).

Boecker, W. et al. Usual ductal hyperplasia of the breast is a committed stem (progenitor) cell lesion distinct from atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. J. Pathol. 198, 458–467 (2002).

Liotta, L. A. et al. Metastatic potential correlates with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen. Nature 284, 67–68 (1980).

Witkiewicz, A. K. et al. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 2023–2034 (2009).

Chen, L. et al. Precancerous stem cells have the potential for both benign and malignant differentiation. PLoS ONE 2, e293 (2007).

Tlsty, T. Cancer: whispering sweet somethings. Nature 453, 604–605 (2008).

Levine, B. & Abrams, J. p53: the Janus of autophagy? Nature Cell Biol. 10, 637–639 (2008).

Qu, X. et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell 128, 931–946 (2007).

Samaddar, J. S. et al. A role for macroautophagy in protection against 4-hydroxytamoxifen-induced cell death and the development of antiestrogen resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2977–2987 (2008).

Vazquez-Martin, A., Oliveras-Ferraros, C. & Menendez, J. A. Autophagy facilitates the development of breast cancer resistance to the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. PLoS ONE 4, e6251 (2009).

White, E. & DiPaola, R. S. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 5308–5316 (2009).

Amaravadi, R. K. et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 326–336 (2007).

Bellodi, C. et al. Targeting autophagy potentiates tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced cell death in Philadelphia chromosome-positive cells, including primary CML stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1109–1123 (2009).

Hoyer-Hansen, M. & Jaattela, M. Autophagy: an emerging target for cancer therapy. Autophagy 4, 574–580 (2008).

Ostenfeld, M. S. et al. Anti-cancer agent siramesine is a lysosomotropic detergent that induces cytoprotective autophagosome accumulation. Autophagy 4, 487–499 (2008).

Schoenlein, P. V., Periyasamy-Thandavan, S., Samaddar, J. S., Jackson, W. H. & Barrett, J. T. Autophagy facilitates the progression of ERα-positive breast cancer cells to antiestrogen resistance. Autophagy 5, 400–403 (2009).

Behrends, C., Sowa, M. E., Gygi, S. P. & Harper, J. W. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature 466, 68–76 (2010).

McPhee, C. K., Logan, M. A., Freeman, M. R. & Baehrecke, E. H. Activation of autophagy during cell death requires the engulfment receptor Draper. Nature 465, 1093–1096 (2010).

Yu, L. et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature 465, 942–946 (2010).

Fung, C., Lock, R., Gao, S., Salas, E. & Debnath, J. Induction of autophagy during extracellular matrix detachment promotes cell survival. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 797–806 (2008).

Evans, A. et al. Lesion size is a major determinant of the mammographic features of ductal carcinoma in situ: findings from the Sloane project. Clin. Radiol. 65, 181–184 (2010).

Evans, A. J. et al. Screening-detected and symptomatic ductal carcinoma in situ: mammographic features with pathologic correlation. Radiology 191, 237–240 (1994).

Holland, R. et al. Extent, distribution, and mammographic/histological correlations of breast ductal carcinoma in situ. Lancet 335, 519–522 (1990).

Stomper, P. C. & Connolly, J. L. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: correlation between mammographic calcification and tumor subtype. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 159, 483–485 (1992).

Evans, A. J. et al. Correlations between the mammographic features of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and C-erbB-2 oncogene expression. Nottingham Breast Team. Clin. Radiol. 49, 559–562 (1994).

Hermann, G. et al. Mammographic pattern of microcalcifications in the preoperative diagnosis of comedo ductal carcinoma in situ: histopathologic correlation. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 50, 235–240 (1999).

Gao, W., Ding, W. X., Stolz, D. B. & Yin, X. M. Induction of macroautophagy by exogenously introduced calcium. Autophagy 4, 754–761 (2008).

Ducharme, J. & Farinotti, R. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of chloroquine. Focus on recent advancements. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 31, 257–274 (1996).

Loehberg, C. R. et al. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and p53 are potential mediators of chloroquine-induced resistance to mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 67, 12026–12033 (2007).

Rahim, R. & Strobl, J. S. Hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and all-trans retinoic acid regulate growth, survival, and histone acetylation in breast cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs 20, 736–745 (2009).

Savarino, A., Lucia, M. B., Giordano, F. & Cauda, R. Risks and benefits of chloroquine use in anticancer strategies. Lancet Oncol. 7, 792–793 (2006).

Wozniacka, A., Cygankiewicz, I., Chudzik, M., Sysa-Jedrzejowska, A. & Wranicz, J. K. The cardiac safety of chloroquine phosphate treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: the influence on arrhythmia, heart rate variability and repolarization parameters. Lupus 15, 521–525 (2006).

Maclean, K. H., Dorsey, F. C., Cleveland, J. L. & Kastan, M. B. Targeting lysosomal degradation induces p53-dependent cell death and prevents cancer in mouse models of lymphomagenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 79–88 (2008).

Fisher, B. et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 97, 1652–1662 (2005).

Vogel, V. G. The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 9, 51–60 (2009).

Fisher, B. et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 90, 1371–1388 (1998).

Kelloff, G. J. & Sigman, C. C. Assessing intraepithelial neoplasia and drug safety in cancer-preventive drug development. Nature Rev. Cancer 7, 508–518 (2007).

O'Shaughnessy, J. A. et al. Treatment and prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia: an important target for accelerated new agent development. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 314–346 (2002).

Hwang, E. S. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ in BRCA mutation carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 642–647 (2007).

Kwong, A. et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of Chinese patients with BRCA related breast cancer. Hugo J. 3, 63–76 (2009).

Smith, K. L. et al. BRCA mutations in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 4306–4310 (2007).

Arun, B. et al. High prevalence of preinvasive lesions adjacent to BRCA1/2-associated breast cancers. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2, 122–127 (2009).

Deng, C. X. & Scott, F. Role of the tumor suppressor gene Brca1 in genetic stability and mammary gland tumor formation. Oncogene 19, 1059–1064 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program award, W81XWH-07-1-0377, to L.A.L. The authors would like to thank K. Edmiston for her role as clinical PI of the trial described in figure 4. The authors also thank B. Mariani and K. Tran, Genetics & IVF Institute, for genetic analysis of DCIS cells.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Espina, V., Liotta, L. What is the malignant nature of human ductal carcinoma in situ?. Nat Rev Cancer 11, 68–75 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2950

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2950

This article is cited by

-

Understanding autophagy role in cancer stem cell development

Molecular Biology Reports (2022)

-

Comprehensive analysis of the 21-gene recurrence score in invasive ductal breast carcinoma with or without ductal carcinoma in situ component

British Journal of Cancer (2021)

-

Quantification of EGFR family in canine mammary ductal carcinomas in situ: implications on the histological graduation

Veterinary Research Communications (2019)

-

Evaluation of nipple aspirate fluid as a diagnostic tool for early detection of breast cancer

Clinical Proteomics (2018)

-

Construction of a 3D mammary duct based on spatial localization of the extracellular matrix

NPG Asia Materials (2018)