Abstract

Study design:

Multi-centre, single cohort.

Objectives:

To assess the relationship between cognitive appraisals in a spinal cord-injured population living in the community, and examine how these factors affect social participation, life satisfaction and functional outcomes.

Setting:

The National Spinal Injuries Centre, Stoke Mandeville, UK; Princess Royal Spinal Injuries Centre, Sheffield UK; Midlands Centre for Spinal Injuries, Oswestry, UK.

Method:

Participants (n=81) sustaining injury aged 18 or above were recruited from one of three spinal cord injuries units 3–18 months after discharge. Postal packs containing questionnaires, consent forms and information were distributed and a 2-week reminder sent.

Results:

Participation was found to be strongly related to life satisfaction, negative appraisals of disability were found to explain 12.9% of the variance in total participation scores. The variance in scores on Life Satisfaction Questionnaires was explained by appraisals, participation and secondary complications to a total of 69.6%. Functional Independence Scores were explained by negative perceptions of disability, growth and resilience and total secondary complication scores, explaining 49.4% of the variance in this measure.

Conclusion:

Participation, functional independence and life satisfaction were significantly related to appraisal styles in this population. Negative perceptions of disability, fearful despondency and overwhelming disbelief were themes that impacted on the likelihood of participation and independence and involved in expressed levels of life satisfaction. Our results suggest the need to tackle cognitive styles of SCI patients before discharge to improve the rehabilitation process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coping strategies have been a popular focus of investigation when examining the impact of spinal cord injury (SCI) on long-term functioning, participation and adjustment.1, 2, 3 Acceptance of change and modification of life values have both been associated with better psychological well-being; studies have found that individuals showing more ‘acceptance’ and ‘fighting spirit’ display fewer signs of anxiety and depression.4 Research comparing emotion-focused and task-oriented coping strategies has investigated the long-term psychological impact of coping techniques that differ when employed in stressful situations.5 Whereas some individuals channel their resources into problem-solving—cognitive restructuring and attempting to alter a situation to their advantage—others channel their energies into emotional coping which, although offering some reduction in distress, offers few adaptive outcomes and ultimately leaves individuals dissatisfied with their situation.

Societal participation is considered to be one of the most important aims in the rehabilitation of individuals living with spinal cord injury (SCI), and evidence suggests that participation is important to physiological and psychological well being in both disabled and able-bodied populations.6 Overall levels of satisfaction with life and psychological well-being have been found to be related to engagement and social participation in people with SCI living in the community;7 making societal participation of vital importance to rehabilitation outcomes.

In relation to people adjusting to spinal cord injury, the use of maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance and withdrawal will potentially have a detrimental effect on participation and therefore on long-term rehabilitation outcomes.

To improve life satisfaction and outcome, it is therefore of vital importance to identify those people at risk during early stages of community rehabilitation. However, despite previous research suggesting coping strategies to be involved in adjustment to SCI, quality of life and societal participation,2 there remains little explanation as to why one coping strategy may be used in favour of another. In addition, there is also disagreement within the literature as to the relationship between coping strategies and psychological functioning within the SCI population, and it has been suggested that the use of general coping measures in research may be inappropriate for use in SCI populations.1, 8

A recent review has highlighted the significant role of appraisals in the relationship between spinal cord injury, coping and adjustment8 and a significant factor when investigating coping styles. Primary appraisals are defined as an ‘inference about a situation, which can be determined by many other factors’ and involves an initial judgement on potential harm within the environment. A secondary appraisal, on the other hand, involves higher order cognitive processes and an evaluation on the availability of coping resources, their sufficiency in the current environment and the likelihood that they can be used in the current situation.1

By examining these cognitive appraisal processes in relation to both psychological and functional outcomes in SCI, we may further our understanding of clinical variations in coping styles, rehabilitation success and societal participation.

Although there is a well-established link between appraisal styles and coping with stressful situations, there has until recently been no specific measure with which to assess appraisals of disability. The construction of the appraisals of disability: primary and secondary scale4 targets the aforementioned primary and secondary appraisals in relation to injury and disability. Not only is this of value in identifying cognitive styles most pertinent to people with SCI, but also one which may be effectively implemented within the hospital setting and allow early identification of risk. By using this newly constructed measure, we will look at the relationship between appraisals of disability, participation, life satisfaction and functional outcomes in people with spinal cord injury living in the community.

Methods

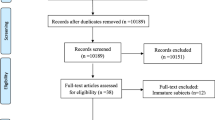

Participants sustaining spinal cord injury aged 18 and over were recruited from one of three spinal injuries centres (National Spinal Injuries Centre; Princess Royal Spinal Injuries Centre; Midlands Centre for Spinal Injuries) 3–18 months post discharge. Two hundred and fifty-five people across the three spinal centres were invited to participate when meeting criteria for having sustained their injury was 18 years or over. Both female and male patients were invited to participate and both traumatic and non-traumatic injuries were included within the sample. Medical clearance was obtained from consultants before distribution of questionnaire packages, which contained relevant information and consent forms. Reminder letters were sent after 2 weeks to reduce attrition rates.

Measures

Functional independence measure

A self-administered scale to examine the level of independence in activities of daily living.9 Each domain is scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (total assistance). It has been validated for use within the SCI population. The scale shows an acceptable internal consistency score in the range of 0.91–0.92 and 0.33–0.81 for the items.3

Craig handicap and assessment-reporting technique (CHART)

Used10 as an objective measure of participation for people with physical disabilities and comprising of six areas: physical independence; cognitive independence; social integration; mobility; occupation and economic self-sufficiency. The highest score is 100 for each domain and suggests a level of participation similar to that of a non-disabled person. The CHART has been used with a spinal cord injury population;9 therefore it is suitable for use with the proposed community sample.

APAPSS Scale

Self Report measure of cognitions used to appraise situations.11 Specifically designed for use within the SCI population and found to demonstrate good internal reliability and validity. Five subscales overwhelming disbelief, fearful despondency, determined resolve, growth and resilience and negative perceptions of disability are contained within the measure. The scale has been found to exhibit acceptable internal consistency and reliability coefficients.4 Since this study was conducted this scale has been revised to include fewer items within the measure.4

Life Satisfaction Questionnaire

A scale examining satisfaction in six life domains:12 social contact with friends, sexual life, partnership relations, family life, vocational and financial circumstances, leisure and self-care. Responses range from dissatisfying (1) to very satisfying (6).

Secondary complication screening instrument

Frequency and impact of secondary problems on independent activity is measured on a likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3.13 Items were selected as those which were most relevant to the SCI population; pressures sores, spasticity, contractures, fatigue, urinary tract infections, respiratory problems and sleep problems and disturbances.

All three centres were involved in data collection, and analysis was conducted at the NSIC, Stoke Mandeville Hospital using SPSS for Windows. Data were dealt with in accordance to ethical guidelines and data protection laws.

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Response rates

Two hundred and fifty-five people were invited to take part in the study. Overall, 81 participants responded to the questionnaire giving a response rate of 31.8% and representative of the average response rate for postal questionnaires. Individual response rates from each centre were 32.5% for NSIC, 26.7% for PRSIC and 38.2% for MCSI.

Demographics

Mean age was 50.37 years, a range of 18–81 and a ratio of 2:1 males/females. A total of 32% (26) of the respondents were employed at the time of the study with a further 7.6% actively seeking employment. Injury characteristics were as follows:

Eight participants (10%) had complete tetraplegia, 23 (29%) had incomplete tetraplegia, 17 (21%) had complete paraplegia, 23 (29%) has incomplete paraplegia and 9 (11%) did not indicate their injury type.

Relationship between appraisals and participation

Correlational analyses found several strong relationships between the subscales of CHART and the ADAPSS. As can be seen in Table 2, the strongest negative correlation was between the appraisal ‘negative perceptions of disability’ and cognitive independence (r=−0.607, P<0.001). Strong correlations were also found between the appraisal ‘negative perceptions of disability’ and mobility, (r=−0.465, P<0.001), occupation, (r=−0.500, P<0.001) and social integration, (r=−436, P<0.001), suggesting this to be an important factor when investigating low participation in the spinal cord-injured population.

Hierarchical regression analyses were performed using CHART total as the dependent variable. Demographic and injury variables were entered at step one, ADAPSS subscales at step two. The model explained 12.9% of the variance in CHART scores with no effect of demographic variables on participation levels. Results of the regression model are displayed in Table 2.

Relationship between appraisals and life satisfaction

Significant relationships were found between the ADAPSS subscales and measures of life satisfaction. Strong negative relationships were seen between life satisfaction and the subscales fearful despondency and negative perceptions of disability. As low scores on determined resolve indicate high agreement with statements the correlation observed between this measure and life satisfaction may be understood as a strong positive relationship. Results are shown in Table 1.

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted using the LSQ total as the dependent variable. Demographic and injury variables were entered at step 1, the ADAPSS subscales and CHART total at stage 2. The model explained 49.2% of the variance in LSQ scores, with significant unique contributions from fearful despondency (P<0.001), Overwhelming disbelief (P=0.022), growth and resilience (P=0.023) and CHART totals (P=0.042). Demographic and injury variables did not contribute to the overall variance in life satisfaction. Results of this regression model are displayed in Table 2.

Relationship between appraisals and functional independence

Strong negative correlations were shown between the ADAPSS subscales fearful despondency, overwhelming disbelief and negative perceptions of disability with the functional independence measure. Results are displayed in Table 1.

To investigate the impact of cognitive appraisals on functional outcomes, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. Demographic variables age, gender and completeness of injury were entered in block 1, the impact of secondary complications on activity and the ADAPSS subscales were entered in block two. The model explained 49.4% of the variance in functional independence, with significant unique contributions attributed to determined resolve, negative perceptions of disability and the secondary complications total. Results of this regression model are displayed in Table 2.

Discussion

This preliminary study of 81 persons with spinal cord injury within the first 18 months of discharge provided evidence of a relationship between appraisals, life satisfaction and functional outcomes. Strong relationships were found between the appraisal processes used by participants and the levels of participation in differing domains, and that participation was strongly related to self-reported levels of overall life satisfaction.

The findings from this study clearly highlight the important role of appraisal processes in the rehabilitation, level of life satisfaction and societal participation achieved by persons living with a spinal injury. The most salient appraisal process that this study revealed was negative perceptions of disability. Dean and Kennedy4 suggest that persons using this appraisal process tend to consider their injury as a loss or threat, and more likely to perceive the situation as being unmanageable. As this type of appraisal process means the injury is not seen as a challenge, it is likely that the individual will employ emotion-oriented rather than task-oriented coping strategies. Negative perceptions of disability alone predicted 33% of the variance in functional independence. A possible process in this relationship is that the individual using this appraisal approach will adopt a resigned behavioural response, thus remaining dependent on assistance from others. This style of responding, and the likelihood of it leading to emotion-oriented coping, is likely to lead to more depressive symptomology.4 Research has suggested a link between depression and a greater proportion of sleep disturbances, longer healing times14 and an increased awareness of physiological symptoms such as pain;15 the inclusion of secondary complications in explaining the variance in FIM scores is suggestive of this process. Further to this, previous research has described a mediational model of depressive symptomatology, pain interference and functional ambulation.15 The findings also reflect other research2 whereby persons with spinal cord injuries adopt the coping strategy ‘Social Reliance’, which increases dependent behaviour and the tendency to ‘externalize the control for stressors to other people and rely on their ability’.

Interestingly, overall levels of life satisfaction were not affected by physical ability. Previous research16 suggests that participation tends to decrease during the normal aging process and that adaptation to changing in activity may reflect satisfaction despite increased restriction. This reflects the way in which goals and expectations can change over time17 and lead individuals to re evaluate internal values and standards. The current study found that life satisfaction was unaffected by physical limitations, which supports previous qualitative findings18 in which 51% of participants report other factors as contributing to life satisfaction.

The sample recruited in the current study were recruited relatively early on in the rehabilitation process, and as previously discussed, the ability for personal goals and re-evaluation of priorities is such that the predictive relationships found in the current study may not be extrapolated to individuals having lived with their injury over a longer period of time. However, appraisal patterns are considered to be relatively stable across situations;19 further research would be beneficial considering the long-term consequences of maladaptive appraisals in spinal cord injury rehabilitation.

The current research also highlights the possibility of devising intervention methods for implementation during rehabilitation, to reduce the depression and suicide rates in this population and improve quality of life.

In summary, this study found strong relationships between appraisal processes, quality of life, psychological function and participation in persons living with a spinal cord injury. The authors suggest that the link between empirically reported coping strategies and varying rates of success in rehabilitation may be in the kinds of cognitive appraisals adopted by the individual. By further researching this possibility, the clinical application of devised interventions may improve the psychological well-being and quality of life expressed in the spinal injured population.

References

Galvin LR, Godfrey HPD . The impact of coping on emotional adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI): review of the literature and application of a stress appraisal and coping formulation. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 615–627.

Elfström ML, Rydén A, Kreuter M, Persson L-O, Sullivan M . Linkages between coping and psychological outcome in the spinal cord lesioned: development of SCL-related measures. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 23–29.

Elfström ML, Rydén A, Kreuter M, Taft C, Sullivan M . Relations between coping strategies and health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord lesion. J Rehabil Med 2005; 37: 9–16.

Dean R, Kennedy P . Measuring appraisals following spinal cord injury: a preliminary psychometric analysis of the appraisals of disability. Rehabil Psychol 2009; 54: 222–231.

Takaki J, Yano E . The relationship between coping with stress and employment in patients receiving maintenance haemodialysis. J Occup Health 2006; 48: 276–283.

Ostir GV, Ottenbacher KJ, Fried LP, Guralnik JM . The effect of depressive symptoms on the association between functional status and social participation. Soc Indic Res 2007; 80: 379–392.

Fuhrer MJ, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Clearman R, Young ME . Relationship of life satisfaction to impairment, disability, and handicap among persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 552–557.

Chevalier Z, Kennedy P, Sherlock O . Spinal cord injury coping adjustment: a literature review. Spinal Cord (e-pub ahead of print 2009).

Hamilton BB, Granger C, Heinemann AW, Linacre JM, Wright BD . Relationships between impairment and physical disability as measured by the functional independence measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 566–573.

Whiteneck GG, Brooks CA, Charlifue S, Gerhart KA, Mellick D, Overholser D et al. Guide for use of the CHART: Craig Handicap and Assessment Reporting Technique, 1992.

Dean R, Kennedy P . Measuring Appraisals Following Acquired Spinal Cord Injury, Unpublished doctoral dissertation University of Oxford: UK, 2008.

Fugl-Meyer AR, Branholm IB, Fugl-Meyer KS . Happiness and domain specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehabil 1991; 5: 25–33.

Seekins T, Smith N, McCleary T, Clay J, Walsh J . Secondary disability prevention: Involving consumers in the development of a public health surveillance instrument. J Disabil Policy Stud 1990; 1: 21–35.

Cole-King A, Harding KG . Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med 2001; 63: 216–220.

Krause JS, Brotherton SS, Morrisette DC, Newman SD, Karakostas TE . Does pain interference mediate the relationship of independence in ambulation with depressive symptoms after spinal cord injury? Rehabil Psychol 2007; 52: 162–169.

Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, St-Cyr Tribble D . Do quality of life, participation and environment of older adults differ according to level of activity? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 30.

Schwartz CE, Andreson EM, Nosek MA, Krahn GL . Response shift theory: important implications for measuring quality of life in people with a disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 8: 529–536.

Kennedy P, Sherlock O, McClelland M, Short D, Royle J, Wilson C . A multi-centre study of the community needs of people with spinal cord injuries: the first eighteen months. Spinal Cord 2008 (e-pub ahead of print 2009).

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A . Appraisals, coping, health status and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 50: 571–579.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and patients from the National Spinal Injuries Centre, Stoke Mandeville; the Princess Royal Spinal Injuries Centre, Sheffield; and the Midlands Centre for Spinal Injuries, Oswestry, for their contributions and participation in this study. Special thanks to Olivia Sherlock, who assisted in the data collection for this study. The authors are grateful to UK spinal cord injury research network (UKSCIRN) who funded this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennedy, P., Smithson, E., McClelland, M. et al. Life satisfaction, appraisals and functional outcomes in spinal cord-injured people living in the community. Spinal Cord 48, 144–148 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.90

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.90

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive appraisals of disability in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury: a scoping review

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Satisfaction scores can be used to assess the quality of care and service in spinal rehabilitation

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Media portrayal of spinal cord injury and its impact on lived experiences: a phenomological study

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Cognitive appraisals and emotional status following a spinal cord injury in post-acute rehabilitation

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Characteristics associated with low resilience in patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders

Quality of Life Research (2013)