Abstract

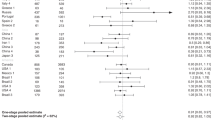

In a pooled analysis of two prospective studies with 35 004 Japanese women, green-tea intake was not associated with a lower risk of breast cancer (222 cases), the multivariate relative risk for women drinking ⩾5 cups compared with <1 cup per day being 0.84 (95% confidence interval 0.57–1.24, Trend P=0.69).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although laboratory studies have suggested a protective effect of green tea on breast cancer risk, few epidemiological studies have examined the association. A case–control study of Asian Americans in the United States found a lower risk of breast cancer in association with green-tea intake (Wu et al, 2003), whereas a prospective cohort study in Japan found no association (Key et al, 1999). To further examine the association between green-tea consumption and the risk of breast cancer, we conducted a pooled analysis of two population-based prospective cohort studies among women in rural northern Japan.

Materials and methods

Details of the design of the two cohort studies are described elsewhere (Tsubono et al, 2001; Nakaya et al, 2003). Briefly, Cohort 1 started in 1984 and included 17 353 women aged ⩾40 years (94% response rate) (Tsubono et al, 2001); Cohort 2 started in 1990 and included 24 769 women aged 40–64 years (93% response rate) (Nakaya et al, 2003). Self-administered questionnaires covered recent (Cohort 1) or usual (Cohort 2) consumption of green tea and used the same five frequency categories ranging from ‘never’ to ‘⩾5 cups per day’. It had a reasonably high level of validity and reproducibility (Ogawa et al, 2003). After exclusion of those with missing responses or with a prior history of cancer, 14 409 subjects in Cohort 1 and 20 595 in Cohort 2 remained. We followed up vital and residential status of the study subjects by population registries. Through population-based cancer registries, 103 incident cases of breast cancer were identified in Cohort 1 (9 years follow-up with 111 267 person-years) and 119 in Cohort 2 (7 years follow-up with 151 882 person-years).

We estimated relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of breast cancer according to green-tea consumption, using Cox's proportional-hazards regression with the adjustment for age and potential confounders. To obtain a summary measure of results between Cohorts 1 and 2, the general variance-based method was used to pool each RR and 95% CI. We repeated all analysis after excluding breast cancer cases diagnosed in the first 3 years of follow-up (38 in Cohort 1 and 40 in Cohort 2). P-values for the test of linear trend were calculated by treating the green-tea consumption category as an ordinal variable. All reported P-values are two-tailed.

Results

Table 1 compares the characteristics of subjects in the highest and the lowest categories of green-tea consumption. Subjects in Cohort 1 with higher intake tended to be postmenopausal, while such women in Cohort 2 tended to be slightly older, postmenopausal and have a higher body mass index. Subjects in both cohorts with a lower intake tended to drink black tea less frequently and coffee more frequently.

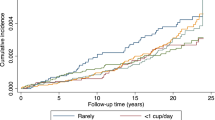

We found no inverse association between green-tea intake and the risk of breast cancer, whether data for Cohorts 1 and 2 were combined or separated (Table 2). Exclusion of cases of breast cancer diagnosed in the first 3 years of follow-up did not substantially change the results and nor did further adjustment for consumption frequencies of vegetables, fruits and meat.

When we performed stratified analyses according to variables used as potential confounders in the multivariate analysis, the association between the consumption of green tea and breast cancer risk was not substantially modified. In a stratified analysis according to soybean soup intake (less than daily and daily), the pooled multivariate RRs (95% CI) of breast cancer for women who drank five or more cups per day, as compared with women who drank less than one cup per day, were 0.95 (0.29–3.10; Trend P=1.00) among those consuming soybean soup less than daily (35 cases) and 0.81 (0.54–1.24; Trend P=0.63) among those consuming soybean soup daily (185 cases).

We found no relation between breast cancer risk and the consumption of black tea and coffee. The pooled multivariate RRs (95% CI) compared with women who never drank black tea were 0.90 (0.64–1.27) for those drinking black tea occasionally and 1.44 (0.77–2.69) for those drinking one or more cups per day (Trend P=0.81). The corresponding risks for coffee were 0.78 (0.53–1.13) and 0.81 (0.55–1.18) (Trend P=0.44).

Discussion

We found no association between green-tea consumption and breast cancer incidence among Japanese women who consumed green tea much more frequently than women in Western countries. The results agree with a prospective study (Key et al, 1999) but disagree with a case–control study (Wu et al, 2003). In the latter paper, the authors suggested that breast cancer risk might be influenced by the intake of both green tea and soy, and that the benefit of green tea was primarily observed among subjects who were low soy consumers. We examined this possibility but found no differential association between green-tea consumption and the risk of breast cancer among high and low consumers of soybean soup.

Two hospital-based cohort studies (Nakachi et al, 1998; Inoue et al, 2001) observed a nonsignificant lower risk of recurrence among high green-tea consumers than among low green-tea consumers with breast cancer, although such an effect may not apply to healthy women.

We also found no relationship between the risk of breast cancer and the consumption of black tea or coffee. Our results are consistent with the judgment of World Cancer Research Fund that it is possible that black tea has no relationship with breast cancer risk and that it is convincing that coffee has no relationship with the risk of breast cancer (World Cancer Research Fund, 1997).

In conclusion, in a pooled analysis of two prospective cohort studies in rural northern Japan, we found no association between consumption of green tea, coffee or black tea and the risk of breast cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Inoue M, Tajima K, Mizutani M, Iwata H, Iwase T, Miura S, Hirose K, Hamajima N, Tominaga S (2001) Regular consumption of green tea and the risk of breast cancer recurrence: follow-up study from the Hospital-based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center (HERPACC), Japan. Cancer Lett 167: 175–182

Key TJ, Sharp GB, Appleby PN, Beral V, Goodman MT, Soda M, Mabuchi K (1999) Soya foods and breast cancer risk: a prospective study in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. Br J Cancer 81: 1248–1256

Nakachi K, Suematsu K, Suga K, Takeo T, Imai K, Higashi Y (1998) Influence of drinking green tea on breast cancer malignancy among Japanese patients. Jpn J Cancer Res 89: 254–261

Nakaya N, Tsubono Y, Hosokawa T, Nishino Y, Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Shibuya D, Fukudo S, Fukao A, Tsuji I, Hisamichi S (2003) Personality and the risk of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 799–805

Ogawa K, Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, Watanabe Y, Ohkubo T, Watanabe T, Nakatsuka H, Takahashi N, Kawamura M, Tsuji I, Hisamichi S (2003) Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for cohort studies in rural Japan. Public Health Nutr 6: 147–157

Tsubono Y, Nishino Y, Komatsu S, Hsieh CC, Kanemura S, Tsuji I, Nakatsuka H, Fukao A, Satoh H, Hisamichi S (2001) Green tea and the risk of gastric cancer in Japan. N Engl J Med 344: 632–636

World Cancer Research Fund (1997) Coffee, tea, and other drinks. In Food, Nutrition and The Prevention of Cancer. A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research pp 467–471

Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Hankin J, Pike M (2003) Green tea and risk of breast cancer in Asian Americans. Int J Cancer 106: 574–579

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, Y., Tsubono, Y., Nakaya, N. et al. Green tea and the risk of breast cancer: pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Br J Cancer 90, 1361–1363 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601652

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601652

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Green tea consumption and mortality in Japanese men and women: a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan

European Journal of Epidemiology (2019)

-

Tea consumption and the risk of five major cancers: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies

BMC Cancer (2014)

-

Green tea intake is associated with urinary estrogen profiles in Japanese-American women

Nutrition Journal (2013)

-

Black tea, green tea and risk of breast cancer: an update

SpringerPlus (2013)

-

Coffee consumption and risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of cohort studies

BMC Cancer (2011)