Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The incidence of morbidities among home-cared neonates in rural areas has not been studied.

OBJECTIVES:

-

1

To estimate the incidence of various neonatal morbidities and the associated risk of death in home-cared neonates in rural setting.

-

2

To estimate the variation in the incidence of neonatal morbidities by season and by day of life.

-

3

To identify the scope for prevention of morbidities and suggest a hypothesis.

STUDY DESIGN:

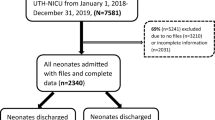

A prospective observational study nested in the first year of the field trial in rural Gadchiroli, India. Trained village health workers in 39 villages observed neonates at the time of birth and in subsequent eight home visits up to 28 days. We diagnosed 20 neonatal morbidities by using clinical definitions. The data were analyzed for the incidence, case fatality, and relative risk of death and for the seasonal and day-wise variation in the incidence of morbidities.

RESULTS:

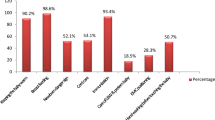

We observed total 763 neonates in 1 year. The incidence of morbidities was a mean of 2.2 morbidities per neonate. The case fatality in 13 morbidities was >10%. Only 2.6% neonates were seen or treated by a physician, and 0.4% were hospitalized. Hypothermia, fever, upper respiratory symptoms, umbilical and skin infections, and conjunctivitis showed statistically significant seasonal variation. Although the morbidities were concentrated in the first week of life, new cases continued to appear throughout the neonatal period. Various morbidities showed different distribution of incidence during 1 to 28 days.

CONCLUSIONS:

A large burden of disease occurs in rural home-cared neonates, and many morbidities are associated with high case fatality. Some morbidities show strong seasonal and day-wise variation in incidence, indicating poor care at home. We hypothesize that changes in practices and better home-based care will prevent the seasonal and temporal increase in morbidities. Some morbidities may not be preventable and will need early detection and treatment. Therefore, frequent home visits by a health worker are necessary to identify sick neonates.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Deshmukh MD, Reddy HM . Burden of morbidities and the unmet need for health care in rural neonates — a prospective observational study in Gadchiroli, India. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:952–965.

Murray LJ, O’Reilly DP, Betts N, Patterson CC, Davey Smith G, Evans AE . Sesaon and outdoor ambient temperature: effect on birth weight. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:689–695.

Matsuda S, Sone T, Doi T, Kahyo H . Seasonality of mean birth weight and mean gestational period in Japan. Hum Biol 1993;65:481–501.

Van Hnswijck de Jonge L, Waller G, Stettler N . Ethnicity modifies seasonal variations in birth weight and weight gain of infants. J Nut 2003;133:1415–1418.

Bantje H . Seasonality of births and birthweights in Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 1987;24:733–739.

Hort KP . Seasonal variation of birthweight in Bangladesh. Ann Trop Paediatr 1987;7:66–71.

Fallis G, Hilditch J . A comparison of seasonal variation in birthweights between rural Zaire and Ontario. Can J Public Health. Rev Can Sante Publique 1989;80:205–208.

Matsuda S, Hiroshige Y, Furuta M, Doi T, Sone T, Kahyo H . Geographic differences in seasonal variation of mean birth weight in Japan. Hum Biol 1995;67:641–656.

Cooperstock M, Wolfe RA . Seasonality of pre-term birth in the Collaborative Perinatal Project: demographic factors. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:234–241.

Keller CA, Nugent RP . Seasonal patterns in perinatal mortality and preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol 1983;118:689–698.

Lajinian S, Hudson S, Applewhite L, Feldman J, Minkoff HL . An association between the heat–humidity index and preterm labor and delivery: a preliminary analysis. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1205–1207.

Costello A . New methods for monitoring neonatal hypothermia and cold stress In: Costello A, Manandhar D, editors. Improving Newborn Infant Health in Developing Countries. London: Imperial College Press; 2000. p. 221–232.

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Arvin AM . Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Sauders Company; 1996.

Taeusch HW, Ballard RA, Avery ME . Schaffer and Avery's Diseases of the Newborn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1991.

Remington JS, Klein JO . Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2001.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD . Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999;354:1955–1961.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD . Methods and the baseline situation in the field trial of home-based neonatal care in Gadchiroli, India. J Perinatol 2005;25:S11–S17.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Morankar VP, Sontakke PG, Solanki, JM . Pneumonia in neonates: can it be managed in the community? Arch Dis Childhood 1993;68:550–556.

Bang AT, et al. Reduction in pneumonia mortality and total childhood mortality by means of community-based intervention trial in Gadchiroli, India. Lancet 1990;336:201–206.

Singh M, Paul VK, Bhakoo ON . Neonatal Nomenclature and Data Collection. New Delhi: National Neonatology Forum; 1989. p. 63–74.

Bang RA, Bang AT, Baitule MB . High prevalence of gynaecological diseases in rural Indian women. Lancet 1989;i:85–88.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was financially supported by The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation, Saving Newborn Lives, Save the Children, USA, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation.

Appendix A1

Appendix A1

Diagnostic Definitions of the Neonatal Health Problems

-

1

Birth asphyxia

-

i)

Mild: At 1 minute after birth, no cry, or the breath was absent or slow, weak or gasping.

-

ii)

Severe: At 5 minutes after birth, the breath was absent or slow, weak or gasping.

-

iii)

Indirect: In the absence of direct observations by VHWs about newborn's condition at 1 and 5 minutes, presence of the following:

-

a)

baby did not cry on its own, so the care provider had to make efforts to make the baby cry; and

-

b)

color of the umbilical cord was green or yellow.

-

a)

-

i)

-

2

Preterm: Less than 8 months and 14 days (37 weeks) of gestation counted from the onset of the last menstrual period as per the history given by the mother.

-

3

LBW: Weight less than 2500 g.

-

4

Delayed breast feeding: Due to traditional practice, breast feeding not started in first 24 hours after birth, but baby licked/sucked the sweetened water.

-

5

Problems in breast feeding: Presence of any one of the following:

-

i)

Baby did not suck breast for more than continuous 8 hours even when offered.

-

ii)

-

Mother unable to breast feed, or

-

baby fed on extracted breast milk, goat, or cow milk, or by bottle, or on sweetened water beyond 3 days, or

-

inadequate breast milk evidenced by continuous crying of baby and failure to gain weight.

-

-

i)

-

6

Diarrhea: Watery, liquid motions three or more, or >9 motions of normal consistency in 24 hours, or mucus or blood in liquid stool.

-

7

Neonatal sepsis (septicemia, meningitis, or pneumonia diagnosed clinically): Simultaneous presence of any two of the following six criteria any time during 0 to 28 days:

-

i)

Baby which cried well at birth, its cry became weak or abnormal, or stopped crying; or baby who earlier sucked or licked well stopped sucking, or mother feels that sucking became weak or reduced; or baby who was earlier conscious and alert became drowsy or unconscious.

-

ii)

Skin temperature >99 or <95°F.

-

iii)

Sepsis in skin or umbilicus.

-

iv)

Diarrhea or persistent vomiting or distention of abdomen.

-

v)

Grunt or sever chest indrawing.

-

vi)

Respiratory rate (RR) 60 or more per minute even on counting twice.

-

i)

-

8

Hemorrhage: bleeding from mouth, anus, eyes, nose, or in skin or in urine any time or vaginal bleeding after first week.

-

9

Conjunctivitis: Mother complained of excessive discharge from the eyes of baby, and on examination, eyes were red and with purulent discharge or dried pus.

-

10

Skin infection:

-

i)

Pyoderma: Pus, ulcer, boil, pustule in skin.

-

ii)

Intertigo: Excoriation with moist, cracked skin at skin folds.

-

i)

-

11

Abnormal jaundice: Skin or eyes yellow on the first day or yellowness persisted at 3 weeks, or when yellowness associated with sepsis.

-

12

Meconium aspiration: History of difficult delivery or presence of birth asphyxia and respiratory distress (RR 60 or more; or severe indrawing of lower chest) started in first 24 hours after birth.

-

13

Hyaline membrane disease: Respiratory distress started within 6 hours after birth in preterms baby.

-

14

Pneumonia: RR 60 or more, persistent even when counted twice (Increased RR when associated with other signs symptoms of sepsis was included in neonatal sepsis).

-

15

Upper respiratory symptoms: Cough or nasal discharge present for 3 days or more without respiratory distress or increased RR.

-

16

Hypothermia: Axillary temperature <95°F.

-

17

Umbilical infection: Pus discharge from umbilicus.

-

18

Tetanus: Baby which earlier sucked well, stopped taking feeds from fourth day or more; and appearance of seizures, spasm and trismus.

-

19

Convulsive Disorder: Seizures but baby conscious, alert and feeds well between seizures (excludes tetanus, asphyxia, sepsis).

-

20

Unexplained fever: Axillary temperature >99°F without any attributable cause.

-

21

Failure to gain weight: Total weight gain during 0 to 28 days <300 g.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bang, A., Reddy, H., Baitule, S. et al. The Incidence of Morbidities in a Cohort of Neonates in Rural Gadchiroli, India: Seasonal and Temporal Variation and a Hypothesis About Prevention. J Perinatol 25 (Suppl 1), S18–S28 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211271

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211271

This article is cited by

-

Non-linear association between admission temperature and neonatal mortality in a low-resource setting

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

State of newborn health in India

Journal of Perinatology (2016)

-

The global burden of neonatal hypothermia: systematic review of a major challenge for newborn survival

BMC Medicine (2013)

-

Neonatal hypothermia and associated risk factors among newborns of southern Nepal

BMC Medicine (2010)

-

Care-seeking behavior and out-of-pocket expenditure for sick newborns among urban poor in Lucknow, northern India: a prospective follow-up study

BMC Health Services Research (2009)