Abstract

Disturbed circadian rhythms have been observed in seasonal affective disorder (SAD). The aim of this study was to further investigate this connection, and to test for potential association between polymorphisms in circadian clock-related genes and SAD, seasonality (seasonal variations in mood and behavior), or diurnal preference (morningness–eveningness tendencies). A total of 159 European SAD patients and 159 matched controls were included in the genetic analysis, and subsets were screened for seasonality (n=177) and diurnal preference (n=92). We found that diurnal preference was associated with both SAD and seasonality, supporting the hypothesis of a link between circadian rhythms and seasonal depression. The complete case–control material was genotyped for polymorphisms in the CLOCK, Period2, Period3, and NPAS2 genes. A significant difference between patients and controls was found for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser (χ2=9.90, Bonferroni corrected P=0.035), indicating a recessive effect of the leucine allele on disease susceptibility (χ2=6.61, Bonferroni corrected P=0.050). Period3 647 Val/Gly was associated with self-reported morningness–eveningness scores (n=92, one-way ANOVA: F=4.99, Bonferroni corrected P=0.044), with higher scores found in individuals with at least one glycine allele (t=3.1, Bonferroni corrected P=0.013). A second, population-based sample of individuals selected for high (n=127) or low (n=98) degrees of seasonality, was also genotyped for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser. There was no significant difference between these seasonality extreme groups, and none of the polymorphisms studied were associated with seasonality in the SAD case–control material (n=177). In conclusion, our results suggest involvement of circadian clock-related polymorphisms both in susceptibility to SAD and diurnal preference.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

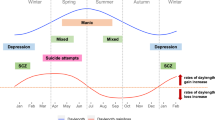

Traits and symptoms of affective disorders appear to interweave with circadian clock work and rhythms in both seasonal and nonseasonal forms of depression (Bunney and Bunney, 2000). Manipulations of the sleep–wake cycle and circadian phase have proven beneficial for some patients; for example, sleep deprivation can give a temporary remission from a depressive episode (Wirz-Justice and Van den Hoofdakker, 1999) and morning bright light therapy is currently the treatment of choice for recurrent winter depression, or seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (Rosenthal et al, 1984a). SAD is often accompanied with atypical depressive symptoms including increased sleep, overeating, and craving for carbohydrates (Partonen and Lönnqvist, 1998). In addition to hypersomnia, there are also results from physiological and endocrine studies implying circadian irregularities in SAD. Abnormalities in the diurnal rhythm of core body temperature, cortisol, and melatonin secretion have been reported in some, but not all, studies (Lam and Levitan, 2000). Patients with SAD seem to generate a melatonin-dependent signal that is absent in healthy volunteers and that is similar to the signal that mammals use to regulate seasonal changes in their behavior (Wehr et al, 2001). While not proving causality, this recent finding agrees with the view that the neural circuits that mediate the effects of seasonal changes in daylight on behavior also mediate effects of light therapy on SAD. It has been suggested that at least a subset of the patients have a phase delay, which can be corrected by morning light exposure (Lewy et al, 1987). The antidepressant effect of light appears greatest when adjusting the time of administration to the early morning of the individual circadian time of the patient (Terman et al, 2001).

Results from family and twin studies point to genetic components in SAD (Sher, 2001), seasonality (seasonal variations in mood and behavior) (Madden et al, 1996; Jang et al, 1997), and diurnal preference (morningness–eveningness tendencies) (Vink et al, 2001). Genetic variations in genes involved in the endogenous circadian clock could have an influence on the deviations from the normal 24-h daily rhythm found in patients with affective disorder (Bunney and Bunney, 2000; Desan et al, 2000). The core of this molecular clock consists of a transcription–translation feedback loop that generates a self-sustained circadian oscillation, and can be adjusted to the environment by responding to external cues, such as new light/dark conditions (for a review see Albrecht, 2002). The accuracy of this synchronization depends on the response of endogenous clocks, and the intrinsic period of the circadian pacemaker is tightly linked to the behavioral trait of morning or evening activity patterns (Duffy et al, 2001).

We have genotyped European SAD patients and healthy matched controls for four single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes related to intrinsic circadian oscillators; CLOCK 3111 C/T (Katzenberg et al, 1998), Period2 1244 Gly/Glu (NCBI dbSNP database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov): rs934945), Period3 647 Val/Gly (Ebisawa et al, 2001), and NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser (Celera Human SNP Database (www.cds.celera.com): CV2153849). The purpose was to look for association with SAD, seasonality or diurnal preference. All these polymorphisms are located in genes believed to encode for transcription regulatory factors. Mutations in CLOCK and the Period genes cause circadian rhythm disturbances in mice (King et al, 1997; Zheng et al, 2001; Shearman et al, 2000), although disruption of the Period3 gene has only a subtle effect (Shearman et al, 2000). NPAS2, or neuronal PAS domain protein 2, is a functional analogue of CLOCK, but unlike the other three genes it is not expressed in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus, where the master pacemaker of the mammalian circadian system resides (Shearman et al, 1999). However, NPAS2 is expressed in the frontal association/limbic forebrain pathway, in nuclei essential for sensory processing and emotions such as fear and anxiety, and is believed to be part of a molecular clock operative in the frontal regions of the brain (Reick et al, 2001). NPAS2 is also suggested to mediate hormonal control of a peripheral clock in the vasculature, and to amplify dampened signals in the peripheral tissues (McNamara et al, 2001).

To our knowledge, none of these polymorphisms have previously been investigated with regard to SAD. There are studies reporting that CLOCK 3111 C/T, which is located in the 3′ flanking region of the CLOCK gene, is associated with diurnal preference (Katzenberg et al, 1998), but not major depressive disorder (Desan et al, 2000), and Period3 647 Val/Gly is suggested to be the causative polymorphism in a Period3 haplotype associated with delayed sleep phase syndrome (Ebisawa et al, 2001). There are no published association studies for Period2 1244 Gly/Glu or NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser. However, another Period2 missense mutation, located in the casein kinase1 ɛ binding region, has been found to cause an autosomal dominant form of familial advanced sleep phase syndrome (Toh et al, 2001).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study was approved by local ethical committees and all participating individuals gave written informed consents. All patients referred to the study (129 women and 30 men) attended outpatient psychiatric services and met the DSM-IV criteria for depressive or bipolar disorder with the seasonal (winter) pattern (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) (for a more detailed description of the inclusion criteria, please see Johansson et al, 2001). All individuals were unrelated Caucasians originating from Sweden (88 patients), Finland (41 patients), Austria (19 patients), or Germany (11 patients). The thirteen patients from Finland were diagnosed with bipolar disorder type I, the rest were unipolar. The control individuals (n=159) were matched for ethnicity, nationality, age and sex, and had no history of psychiatric illness. In all, 79 of the patients and 98 of the controls have completed the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ) (Rosenthal et al, 1984b). It was used for the assessment of seasonal variation in the length of sleep, social activity, mood, weight, appetite, and energy level. The sum of these six scales yields the global seasonality score (GSS), which can range from 0 to 24. The mean GSS was 13.9±2.9 (mean±SD) for the patients and 3.7±2.6 for the controls. A total of 46 patients and 46 controls of Swedish or Finnish origin also completed the Horne–Östberg questionnaire (Horne and Östberg, 1976), another self-rating questionnaire that was used for the assessment of preferences for diurnal activity patterns. The sum of this scale gives the global morningness–eveningness score (MES), which can range from 16 to 86. The mean MES was 54.1±5.8 for the patients (when not depressed) and 52.8±4.0 for the controls.

A set of 225 individuals selected for high or low degrees; of seasonality (GSS ≥10 or ⩽2, respectively) from a Swedish population-based sample (n=2620, for a more detailed description, please see Nilsson et al, 1997 and Johansson et al, in press) was also genotyped for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was prepared from blood lymphocytes and genotyping for CLOCK 3111 C/T was performed as described previously (Desan et al, 2000). For the other polymorphisms, standard PCR amplifications were performed using a 50-cycle reaction with annealing temperatures of 63°C forPeriod2 1244 Gly/Glu and 59°C for Period3 647 Val/Gly and NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser. Primer sequences were: Period2 1244 Gly/Glu; CTTCTCTGGGACTCAGCG and CAAGCACCACCTGGTGTACCT, Period3 647 Val/Gly; CCCAGCCATACCTAAATCAG and AGTGTGGTACCTGTCTCTG and for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser; TGGCAGAAGCAGTGGTAAC and AGACTCACCTGTGCCATGG.

The PCR products were analyzed with real-time pyrophosphate DNA sequencing (Alderborn et al, 2000), according to standard protocols provided by the manufacturer (Pyrosequencing, Sweden). One of the PCR primers in each pair was 5′ biotinylated and after denaturing the single-stranded DNA was separated using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin from Dynal, Norway) and sequenced with the following sequencing primers: Period2 1244 Gly/Glu; CGATCCTGTGATTCAAGG, Period3 647 Val/Gly; GGTACCTGTCTCTGGGGGT, and for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser; CTGCTGTGTGAGGTCGCAG. Subsets of the samples were also genotyped using ABI 377 sequencing of the NPAS2 PCR product (n=66) according to standard protocols (Applied Biosystems, USA), or restriction enzyme cleavage with 4 U of Bam HI (Life Technologies, USA) (n=138), or 2 U of Bsm FI (New England Biolabs, USA) (n=58), for selective digestion of the Gly allele of Period2 1244 Gly/Glu and the Val allele of Period3 647 Val/Gly, respectively. The digested products were size separated by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. All samples tested showed identical results with both genotyping methods.

Statistical Analysis

χ2-analysis was used to test for association between SAD and an allele or genotype, or GSS-extreme group and NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser allele or genotype. The same case–control material, as well as the GSS-extreme samples, has previously been genotyped for a polymorphism in the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene (Johansson et al, in press), and therefore P values were Bonferroni corrected for multiple testing of five or two polymorphisms, respectively. A subset of the material (82 patients and 82 controls) has also been investigated for other serotonin-related polymorphisms (Johansson et al, 2001), but because of the limited number of samples this was not corrected for here. The power calculation was performed as described elsewhere (Johansson et al, 2001), assuming α=0.01, β=0.20, and allele frequencies in the control group identical to a previously published study (Katzenberg et al, 1998), or, when there were no previous reports, the observed frequencies. The distribution of GSS or MES within groups under analysis sometimes deviated from the normal distribution (data not shown), and therefore both parametric (one-way ANOVA or unpaired t-test) and nonparametric (Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum) test methods were used when appropriate. Correlation between the MES and the GSS was tested using linear regression. Stata 6 software was used for the statistical analysis and Genepop (http://wbiomed.curtin.edu.au/genepop/) was used to test the genotype distributions for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

RESULTS

Diurnal Preference, SAD, and Seasonality

Diurnal preference was investigated in a subset (n=92) of the Swedish and Finnish patients and controls. The Horne–Östberg morningness–eveningness questionnaire (Horne and Östberg, 1976) was used, specified for when the patients are not depressed. In all, 40 matched case–control pairs completed the test and all individuals had intermediate to moderate scores (between 37 and 67). However, the patients had significantly higher MESs, indicating a stronger preference for morning patterns of activity (mean MES±SD=54.4±4.9 for the patients and 52.6+4.0 for the controls, Wilcoxon rank sum test: z=−2.5, P=0.01). In addition, there was a significant correlation between the MES and GSS (n=78, linear regression; R2=0.065, P=0.02).

Genetic Analysis of SAD and Seasonality

When comparing genotype distributions in SAD patients (n=159) and controls (n=159), a significant difference was found for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser (χ2=9.90, Bonferroni corrected P=0.035, see Table 1), whereas the allele frequencies for this polymorphism were almost identical (80% Ser and 20% Leu in both groups). Only one individual being homozygous for the leucine allele was found in the control group, compared to nine patients, indicating that this genotype might be a risk factor for SAD (χ2=6.61, Bonferroni corrected P=0.050, when assuming a recessive effect of Leu). Gender-specific analysis under a recessive model yielded similar results, although the difference was not significant in men, possibly because of the small number of male participants (women (n=129±129): χ2=6.66, Bonferroni corrected P=0.049, and men (n=30±30): χ2=4.29, Bonferroni corrected P=0.19).

We also genotyped for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser in a second material consisting of 225 individuals from the general Swedish population, selected for high or low degrees of seasonality (GSSs were ⩾10 or ⩽2, respectively). No association was found in this sample set (χ2=2.5, Bonferroni corrected P=0.58, see Table 2), nor was there an association between NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser and GSS among the SAD patients and controls where this had been measured (n=177, Kruskal–Wallis: H=2.05, Bonferroni corrected P>1). Assuming a recessive effect of the leucine allele, based on the findings from the case–control material, as well as separate analysis of SAD patients (n=79) and controls (n=98), gave similar results (data not shown). Analysis of the individual SPAQ items in the population-based material revealed slightly higher appetite and; weight scores in individuals with the leucine allele, although the differences were not statistically significant (Kruskal–Wallis test, uncorrected P values 0.039 and 0.071, respectively).

No significant differences in the genotype or allele frequencies were found between SAD patients and controls for CLOCK 3111 C/T, Period2 1244 Gly/Glu, orPeriod3 647 Val/Gly (for the genotypes: χ2=0.21–3.44, Bonferroni corrected P>0.9, see Table 1). The minimum detectable allelic effect sizes for the different polymorphisms were estimated to odds ratios between 1.7 and 1.9, after accounting for multiple testing. There was no association with GSS (n=177, Kruskal–Wallis: H=0.66–3.68, Bonferroni corrected P>0.8), nor when analyzing patients (n=79) and controls (n=98) separately (data not shown).

No significant deviations were found when testing genotype distributions in SAD patients, controls and GSS extreme groups for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (Bonferroni corrected P values >0.05). However, a P value of borderline significance was found for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser in the control group (Bonferroni corrected P=0.054).

In addition to the results described above, we studied two other reported polymorphisms in clock-relevant genes, Timeless 592 Val/Met (Sangoram et al, 1998) and Casein kinase 1 ɛ415 C/T (dbSNP rs1803339), that were found not to be polymorphic after having genotyped approximately 100 individuals (data not shown). Therefore, these polymorphisms were not analyzed further.

Genetic Analysis of Diurnal Preference

We also found an association between Period3 647 Val/Gly genotype and diurnal preference (n=92, one-way ANOVA: F=4.99, Bonferroni corrected P=0.044). The MES difference between genotype groups was most pronounced in patients (n=46, F=4.81, Bonferroni corrected P=0.065), and in general, individuals with at least one Gly allele tended to have higher MES (mean MES±SD=55.5±4.9, compared to 52.2±4.8 for Val/Val homozygotes, two-tailed unpaired t-test: t=3.1, Bonferroni corrected P=0.013), again especially in the patient group (n=46, mean MES±SD=57.2±4.2 and 52.1±5.9, respectively, t=3.13, Bonferroni corrected P=0.016). There was no association with MES for any of the other polymorphisms studied (one-way ANOVA: 0.2–1.6, Bonferroni corrected P>1).

DISCUSSION

The finding that SAD patients during remission had higher MES than controls support the hypothesis of SAD being associated with circadian rhythms, and is in line with a previous study reporting more eveningness in depressed SAD patients and a shift towards morningness after light therapy (Elmore et al, 1993).

We found a significant difference between SAD patients and controls for the NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser polymorphism, suggesting a recessive effect of the leucine allele. The polymorphism is located outside of the conserved motif domains in the NPAS2 gene and its potential biological effect remains to be elucidated. Since no association was found when studying seasonality in a subset of the sample set, as well as in a second, population-based material, this indicates that NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser might influence the predisposition to SAD rather than the degree of seasonality in general. Even when selecting the most extreme groups in the general population (in this case ca. 5% from each end of the spectrum), the high seasonality group still had lower scores (mean GSS=11) than the SAD patients (mean GSS=14), so maybe this group was not extreme enough to detect an effect of NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser. Also, the polymorphism might only influence some aspects of seasonality and SAD, as indicated by the tendency of higher seasonality in appetite and weight, in individuals with the leucine allele.

Although strictly speaking, the control group did not deviate significantly from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with regard to NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser, the result could indicate an effect of the population structure. However, no deviations were found for the four other polymorphisms tested in the same material. In addition, the NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser genotype distributions did not differ significantly from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium when testing each nationality separately, and pairwise comparison (χ2-tests) between all nationalities revealed no significant differences in control group NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser genotype distribution (all P>0.59, not corrected for multiple testing). The samples were genotyped at least twice, cases and controls together, using a thoroughly validated technology (Nordfors et al, 2002). In addition, a subset of the samples (n=66) was resequenced for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser using another method (for details see Materials and Methods), minimizing the risk for genotyping errors.

Period3 647 Gly was associated with self-reported MESs in the subset of the samples screened for diurnal preference (n=92). Separate analysis of patients and controls gave similar results, but not always with significant P values, probably because of lack of power. Interestingly, the Val allele is conserved in most Period homologues, and so is the surrounding amino-acid sequence that contains putative casein kinase 1ɛ target sites (Ebisawa et al, 2001). Casein kinase 1ɛ-dependent phosphorylation, of at least Period1 and Period2, is believed to be important regulatory steps in the circadian system (Albrecht, 2002). The function of Period3 in the circadian clock is less well defined, but the Period3 647 Gly allele has been suggested to play a role in delayed sleep phase syndrome (Ebisawa et al, 2001).

The lack of association between MES and CLOCK 3111 C/T in this study is in contrast to an earlier report of association between the C allele and eveningness tendencies in a population-based sample (n=410) (Katzenberg et al, 1998), and might be explained by our limited sample size (n=92). Indeed, our results do not exclude minor effects on SAD, GSS, or MES, of the polymorphisms where no associations were found. Also, the findings for NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser and Period3 647 Val/Gly should be considered preliminary until replicated in a larger material.

In conclusion, diurnal preference was associated with both SAD and seasonality in our material, supporting the hypothesis of a link between circadian rhythms and seasonal depression. Our results suggest that two circadian clock-related polymorphisms, NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser and Period3 647 Val/Gly, may be implicated in SAD and diurnal preference, respectively. Whether these polymorphisms are functional in themselves, or whether they reflect linkage disequilibrium with other causative polymorphisms remains to be elucidated. Further work is needed to confirm these findings, including replication in independent sample sets, preferably using methods to control for the risk of population stratification, as well as studies of the possible biological effects of NPAS2 471 Leu/Ser and Period3 647 Val/Gly.

References

Albrecht U (2002). Invited review: regulation of mammalian circadian clock genes. J Appl Physiol 92: 1348–1355.

Alderborn A, Kristofferson A, Hammerling U (2000). Determination of single-nucleotide polymorphisms by real-time pyrophosphate DNA sequencing. Genome Res 10: 1249–1258.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Bunney WE, Bunney BG (2000). Molecular clock genes in man and lower animals: possible implications for circadian abnormalities in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 335–345.

Desan PH, Oren DA, Malison R, Price LH, Rosenbaum J, Smoller J et al (2000). Genetic polymorphism at the CLOCK gene locus and major depression. Am J Med Genet 96: 418–421.

Duffy JF, Rimmer DW, Czeisler CA (2001). Association of intrinsic circadian period with morningness–eveningness, usual wake time, and circadian phase. Behav Neurosci 115: 895–899.

Ebisawa T, Uchiyama M, Kajimura N, Mishima K, Kamei Y, Katoh M et al (2001). Association of structural polymorphisms in the human period3 gene with delayed sleep phase syndrome. EMBO Rep 2: 342–346.

Elmore SK, Dahl K, Avery DH, Savage MV, Brengelmann GL (1993). Body temperature and diurnal type in women with seasonal affective disorder. Health Care Women Int 14: 17–26.

Horne JA, Östberg O (1976). A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness–eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol 4: 97–110.

Jang KL, Lam RW, Livesley WJ, Vernon PA (1997). Gender differences in the heritability of seasonal mood change. Psychiatry Res 70: 145–154.

Johansson C, Smedh C, Partonen T, Pekkarinen P, Paunio T, Ekholm J et al (2001). Seasonal affective disorder and serotonin-related polymorphisms. Neurobiol Dis 8: 351–357.

Johansson C, Willeit M, Levitan R, Partonen T, Smedh C, Del Favero J et al (in press). The serotonin transporter promoter repeat length polymorphism, seasonal affective disorder and seasonality. Psychol Med.

Katzenberg D, Young T, Finn L, Lin L, King DP, Takahashi JS et al (1998). A CLOCK polymorphism associated with human diurnal preference. Sleep 21: 569–576.

King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch MP et al (1997). Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell 89: 641–653.

Lam RW, Levitan RD (2000). Pathophysiology of seasonal affective disorder: a review. J Psychiatry Neurosci 25: 469–480.

Lewy AJ, Sack RL, Miller LS, Hoban TM (1987). Antidepressant and circadian phase-shifting effects of light. Science 235: 352–354.

Madden PA, Heath AC, Rosenthal NE, Martin NG (1996). Seasonal changes in mood and behavior. The role of genetic factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 47–55.

McNamara P, Seo SP, Rudic RD, Sehgal A, Chakravarti D, FitzGerald GA (2001). Regulation of CLOCK and MOP4 by nuclear hormone receptors in the vasculature: a humoral mechanism to reset a peripheral clock. Cell 105: 877–889.

Nilsson L-G, Bäckman L, Nyberg L, Erngrund K, Adolfsson R, Bucht G et al (1997). The Betula prospective cohort study. Memory, health and aging. Aging, Neuropsychol Cognition 4: 1–32.

Nordfors L, Jansson M, Sandberg G, Lavebratt C, Sengul S, Schalling M et al (2002). Large-scale genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms by Pyrosequencing and validation against the 5′ nuclease (Taqman (R)) assay. Hum Mutat 19: 395–401.

Partonen T, Lönnqvist J (1998). Seasonal affective disorder. Lancet 352: 1369–1374.

Reick M, Garcia JA, Dudley C, McKnight SL (2001). NPAS2: an analog of clock operative in the mammalian forebrain. Science 293: 506–509.

Rosenthal NE, Bradt GH, Wehr TA (1984b). Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire. National Institute of Mental Health: Bethesda, MD.

Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y et al (1984a). Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 41: 72–80.

Sangoram AM, Saez L, Antoch MP, Gekakis N, Staknis D, Whiteley A et al (1998). Mammalian circadian autoregulatory loop: a timeless ortholog and mPer1 interact and negatively regulate CLOCK-BMAL1-induced transcription. Neuron 21: 1101–1113.

Shearman LP, Jin X, Lee C, Reppert SM, Weaver DR (2000). Targeted disruption of the mPer3 gene: subtle effects on circadian clock function. Mol Cell Biol 20: 6269–6275.

Shearman LP, Zylka MJ, Reppert SM, Weaver DR (1999). Expression of basic helix–loop–helix/PAS genes in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 89: 387–397.

Sher L (2001). Genetic studies of seasonal affective disorder and seasonality. Compr Psychiatry 42: 105–110.

Terman JS, Terman M, Lo ES, Cooper TB (2001). Circadian time of morning light administration and therapeutic response in winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 69–75.

Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, Eide EJ, Hinz WA, Virshup DM et al (2001). An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Science 291: 1040–1043.

Vink JM, Groot AS, Kerkhof GA, Boomsma DI (2001). Genetic analysis of morningness and eveningness. Chronobiol Int 18: 809–822.

Wehr TA, Duncan Jr WC, Sher L, Aeschbach D, Schwartz PJ, Turner EH et al (2001). A circadian signal of change of season in patients with seasonal affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 1108–1114.

Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH (1999). Sleep deprivation in depression: what do we know, where do we go? Biol Psychiatry 46: 445–453.

Zheng B, Albrecht U, Kaasik K, Sage M, Lu W, Vaishnav S et al (2001). Nonredundant roles of the mPer1 and mPer2 genes in the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 105: 683–694.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to thank Sophie van Gestel for analysis of NPAS2 and individual SPAQ items. This work was funded by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (project number: 10909), the Söderström-Königska foundation, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska Hospital, and Västerbotten County.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, C., Willeit, M., Smedh, C. et al. Circadian Clock-Related Polymorphisms in Seasonal Affective Disorder and their Relevance to Diurnal Preference. Neuropsychopharmacol 28, 734–739 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300121

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300121

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Role of polygenic risk scores in the association between chronotype and health risk behaviors

BMC Psychiatry (2023)

-

Seasonality of brain function: role in psychiatric disorders

Translational Psychiatry (2023)

-

Intake of l-serine before bedtime prevents the delay of the circadian phase in real life

Journal of Physiological Anthropology (2022)

-

Daily, weekly, seasonal and menstrual cycles in women’s mood, behaviour and vital signs

Nature Human Behaviour (2021)

-

The complex genetics and biology of human temperament: a review of traditional concepts in relation to new molecular findings

Translational Psychiatry (2019)