Abstract

Research suggests that clinical symptom dimensions may be more useful in delineating the genetics of bipolar disorder (BD) than standard diagnostic models. To date, no study has applied this concept to data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS). We performed a GWAS of factor dimensions in 927 clinically well-characterized BD patients of German ancestry. Rs9875793, which is located in an intergenic region of 3q26.1 and in the vicinity of the solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 2 gene (SLC2A2), was significantly associated with the factor analysis-derived dimension ‘negative mood delusions’ (n=927; P=4.65 × 10−8, odds ratio (OR)=2.66). This dimension was comprised of the symptoms delusions of poverty, delusions of guilt and nihilistic delusions. In case–control analyses, significant association with the G allele of rs9875793 was only observed in the subgroup of BD patients who displayed symptoms of ‘negative mood delusions’ (allelic χ2 model: PG=0.0001, OR=1.92; item present, n=89). Further support for the hypothesis that rs9875793 is associated with BD in patients displaying ‘negative mood delusions’ symptom, such as delusions of guilt, was obtained from an European American sample (GAIN/TGEN), which included 1247 BD patients and 1434 controls (PEA=0.028, OR=1.27).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric condition that is characterized by fundamental and distinctive distortions of emotion regulation and perception. BD has an equal sex incidence, affects all age groups and has a worldwide lifetime prevalence of approximately 1%. Family and twin studies of BD have provided unequivocal evidence that inherited genetic variation contributes substantially to disease risk,1, 2, 3 and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several risk variants.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Further analyses of these data have suggested that the risk of BD has a substantial polygenic component, involving a large number of common risk alleles of small effect.9

Previous studies of genetic risk for BD have been based on a categorical diagnosis. However, genes that act through specific biological mechanisms are unlikely to have a similar influence on all BD symptoms, and thus association signals for more specific BD subtypes may have been missed. This hypothesis is supported by findings from previous BD studies. In linkage studies, subphenotyping BD patients according to relevant selected features led to the identification of potential susceptibility loci specific to psychotic BD,10, 11, 12, 13 BD with comorbid anxiety10 and BD with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms.14 In candidate gene studies, NRG1,15 5-HTTLPR16 and COMT17 have been implicated in BD with psychotic symptoms, whereas DAOA has been implicated in BD with persecutory delusions.18

The aim of the present study was to test the hypotheses that symptom dimensions derived through a factor analysis approach that takes into account variations in core, and associated symptoms would enable the formation of genetically more homogenous BD subgroups, and that analysis of these subgroups would identify associations missed in GWAS of the broad BD phenotype, despite a reduction in sample size. The GWAS step was performed in BD patients of German ancestry, and the top findings were followed-up in an European American BD sample.

Materials and methods

Sample ascertainment and genotyping

All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocols were approved by the respective institutional review boards or ethics committees.

German sample

The German sample was used in a previous GWAS,8 and in a study exploring copy number variation of a categorical diagnosis of BD.19 These references provide a detailed description of the sampling and genotyping procedures. In brief, the present study included 927 in-patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of BD and 2168 control subjects, all of German ancestry (for sample description see Table 1). The BD diagnoses were assigned on the basis of multiple sources of information, including the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-I),20 the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness (OPCRIT v3.32),21 medical records and family history. All study participants were individually genotyped using Illumina HumanHap550v3 BeadChips, Illumina Human610Quad Beadchips or Illumina Human660Quad BeadChips (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Following stringent quality control, the final GWAS data set was comprised of 378 570 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with a minor allele frequency of at least 10%.

European American sample

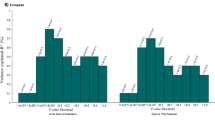

A detailed description of the sample and the genotyping procedure is provided elsewhere.22 The GAIN/TGEN sample included 1247 patients with a best estimate DSM IV diagnosis of either bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder bipolar subtype based on the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS 4.0)23 and 1434 controls. All the study participants were of European American ancestry and were genotyped using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) (Figure 1).

Quantile–quantile (QQ) plot of the genome-wide association data. QQ plot of allelic χ2 test P values from autosomal SNPs following the application of all quality control filters. Good adherence of data points to the line of expectance was observed. This implies that spurious associations, characterized by an increase in the number of potential highly significant P values, had been systematically removed. All remaining slight deviations from the line of expectance in the extreme tail are presumed to reflect true-positive genetic effects.

Factor analysis and the use of factors as binary traits for the association study

To refine the phenotypic characterization of the German BD sample (n=970), we performed a principal component analysis of 48 clinical OPCRIT items (Supplementary Table 1). From this analysis, we derived 12 factor dimensions. In contrast to other rating scales, the OPCRIT has neither a positive nor a negative symptom subscale, either of which might bias symptom rating. Factors derived from OPCRIT ratings are therefore less likely to be statistical artifacts of scale development. Genotypic data were available for 927 of these patients, and these patients were therefore included in the present study. The OPCRIT items referred to appearance and behavior, speech, form of thought, affect, and abnormal beliefs. Missing data varied from approximately 0.8 (excessive activity, suicidal ideation) to 9% (increased sociability). Missing values were replaced by the median for the specific item, taking into account the ordinal characteristic of the OPCRIT data.

We inspected our data to determine whether it would be reasonable to conduct an orthogonal principal component analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) criterion measures the covariance of variables.24 Values above 0.6 indicate variables that are suitable for factor analysis. In our BD data, the KMO sampling adequacy was 0.855. Factor dimensions were extracted according to the commonly used Kaiser–Guttman criterion,25 resulting in a 12-factor solution. Fulfilment of the Kaiser–Guttman criterion indicates that a factor analysis-derived dimension explains more of the variance in clinical symptoms than any single clinical symptom alone. This 12-factor solution explained 54.2% of the total variance in the BD sample. For each patient, a personal regression factor score was calculated for each dimension. The 12-factor dimensions derived in the BD sample were termed: ‘depression’, ‘mania’, ‘delusions’, ‘grandiose delusions’, ‘depersonalization’, ‘voices’, ‘agitation’, ‘disorganization’, ‘other hallucinations’, ‘negative mood delusions’, ‘catatonia’ and ‘negative symptoms’ (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

As the factor dimensions failed to display a normal distribution, the factor scores were transformed to binary format. Factor scores of ⩾1.0 were rated as ‘high scores’, and factor scores of ⩽1.0 as ‘low scores’. A low score indicates that almost none of the items loading on that particular factor were observed in the patient. Each factor dimension was present in around 15% of the BD patients. As all SNPs with a minor allele frequency of ⩾0.1 were included, only factor dimensions present in at least 25 patients from the German sample were analyzed, as expected cell frequencies of <5 would violate one of the premises of the χ2 test. Eleven factor dimensions fulfilled this criterion (‘mania’, ‘delusions’, ‘grandiose delusions’, ‘depersonalization’, ‘voices’, ‘agitation’, ‘disorganization’, ‘other hallucinations’, ‘negative mood delusions’, ‘catatonia’ and ‘negative symptoms’), and were therefore included in the dimensional GWAS.

Statistical analyses for the GWAS and follow-up study

All association analyses were performed using PLINK26 (v1.07). In the single-marker analysis, all of the autosomal SNPs that passed quality control checks were tested for association with the 11 binary factor dimensions using the allelic χ2 model and the Armitage trend test. The P values were corrected using the genomic inflation factor. A P-value of <5 × 10−8 per trait was selected as the threshold for genome-wide significance,27, 28 under the assumption of the presence of one million non-correlated common SNPs in the genome. Adjustment for the number of traits tested appeared too conservative, as factor dimensions were intercorrelated (Supplementary Table 4).

We then explored whether genome-wide significant variants were associated with the categorical diagnosis of BD per se or primarily with a specific BD subphenotype. For this purpose, we tested for association in the entire sample, in subgroups of patients with and without symptoms from the ‘negative mood delusions’ dimension and in a control cohort. In addition, these findings were followed up in an independent European American sample of BD patients. Given that a different diagnostic instrument had been employed in the European American sample, we attempted to find support for our findings on the basis of symptoms rather than factor dimensions. Symptoms with a factor loading of 0.32 (that is, 10% of shared variance between variable and factor) were considered to contribute to the specific factor dimension.29 The P values of the follow-up sample were corrected using the genomic inflation factor.

Results

Factor analysis resulted in a 12-factor solution. Eleven factor dimensions fulfilled the statistical premises for inclusion in the GWAS (‘mania’, ‘delusions’, ‘grandiose delusions’, ‘depersonalization’, ‘voices’, ‘agitation’, ‘disorganization’, ‘other hallucinations’, ‘negative mood delusions’, ‘catatonia’ and ‘negative symptoms’; see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

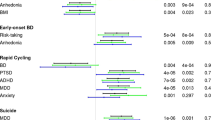

The association between the rs9875793 G allele and the factor dimension ‘negative mood delusions’ (delusions of poverty, delusions of guilt and nihilistic delusions, see Supplementary Table 5) surpassed the threshold for genome-wide significance of P <5 × 10−8 under the assumption of an allelic χ2 model (PG=4.65 × 10−8, odds ratio (OR)=2.66; factor present, n=88). One additional SNP—rs1499821—showed a trend towards genome-wide significance (PG=5.8 × 10−8, OR=2.65; factor present, n=88). Rs9875793 is located in the vicinity of the solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 2 gene SLC2A2. Rs1499821, which is in complete linkage disequilibrium (D′=1.0, r2=0.925) with rs9875793, is located within this gene. Analysis of the seven intragenic SLC2A2 SNPs represented on the array revealed that four (rs5398, rs1499821, rs8192675, rs11924032) were significantly associated with the factor dimension ‘negative mood delusions’ (P<0.05, with Bonferroni correction for seven SNPs) in the combined sample (see Table 2, Figure 2). Association with rs9875793 was only found for ‘negative mood delusions’. No nominally significant association was found with any other factor dimension.

Regional-association plots displaying rs9875793 and the SCL2A2 SNPs. Allelic χ2 test P values from SNPs are plotted against positions from the March 2006 human reference sequence, annotated by RefSeq genes. The most highly associated marker from the combined analysis (P) is indicated by an enlarged red diamond, which is in the center of a genomic window of around 300 Mb. The strength of linkage disequilibrium (in r2) between the top SNP and its adjacent markers is demonstrated by the red (high) to white (low) color bar (top right corner).

Exploration of the association in the entire sample and in subgroups of patients with and without symptoms from the ‘negative mood delusions’ dimension in comparison to a control cohort (n=2168) revealed that a significant association with the G allele of rs9875793 was only present in the subgroup of patients with ‘negative mood delusions’ symptom (n=89) (allelic χ2 model: PG=0.0001, OR=1.92).

The only ‘negative mood delusions’ symptom rated in the European American follow-up sample (GAIN/TGEN) was delusions of guilt or sin. This corresponds to delusions of guilt in the German sample (item present, n=83; mapping 93% of the patients with the ‘negative mood delusions’ symptom). This symptom also showed significant association with the G allele in a separate single item analysis (allelic χ2 model: PG=0.0008, OR=1.87; see Supplementary Table 6). This association in the European American sample was in the same direction as that identified in the German sample (allelic χ2 model: PEA=0.028, OR=1.27). In the European American BD sample, no such association was observed in either the total sample or in patients without this symptom, in comparison to controls (see Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present GWAS of BD is the first to be based on factor analysis-derived symptom dimensions. We hypothesized that subsampling of patients according to selected clinical features would enable identification of novel genetic associations that would be missed in analyses of a broad BD phenotype. Using this new approach, we were able to identify a genome-wide significant association between the factor dimension ‘negative mood delusions’ (delusions of poverty, delusions of guilt and nihilistic delusions) and the chromosome 3 variant rs9875793 (PG=4.65 × 10−8, OR=2.66).

Rs9875793 is located in an intergenic region on chromosome 3, approximately 28 kb downstream of the glucose transporter gene SLC2A2. The cortically expressed SLC2A2 gene30 is a promising candidate gene for BD, as it is involved in the lithium-sensitive phosphatidyl inositol pathway,31 and its expression is modulated by psychological stress.32 Additionally, our top SNP rs9875793 was recently reported to be associated with differing activity of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during a working memory paradigm in patients with schizophrenia in comparison to healthy controls.33 The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is a critical interface between emotion regulation and cognition, and is particularly involved in the processing of negative emotions.34, 35 Structural and functional abnormalities in this region have been reported in patients with BD, schizophrenia and major depression.33, 36, 37

Case–control analyses revealed a unique association between the G allele of rs9875793 and BD patients with ‘negative mood delusions’ compared with controls, and this association was also observed in an independent European American BD sample. The fact that not even a trend toward association with the G allele of rs9875793 was observed for the categorical diagnosis of BD may suggest that patients with ‘negative mood delusions’ symptom constitute a biologically more homogenous BD subgroup.

The present results indicate that BD patients characterized by the factor dimension ‘negative mood delusions’ may represent a genetically more homogenous subgroup. A limitation of the present study is that no stringent adjustment was made for the number of factor dimensions included. However, as our finding gained further support in the follow-up study, we consider our finding to be robust. The present study also underlines the feasibility of the factor dimensional approach, as it allows subphenotyping in clinical practice. Screening for the presence of particular symptoms might allow the identification of genetically more homogenous BD subgroups, which may in turn facilitate the development of individual treatment strategies.

References

Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Bjork C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet 2009; 373: 234–239.

Kieseppä T, Partonen T, Haukka J, Kaprio J, Lönnqvist J . High concordance of bipolar I disorder in a nationwide sample of twins. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 1814–1821.

McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A . The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: 497–502.

Chen DT, Jiang X, Akula N, Shugart YY, Wendland JR, Steele CJ et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of European and Asian-ancestry samples identifies three novel loci associated with bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry advance online publication, 20 December 2011 doi:10.1038/mp.2011.157.

Sklar P, Ripke S, Scott LJ, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Craddock N et al. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 977–983.

Baum AE, Hamshere M, Green E, Cichon S, Rietschel M, Noethen MM et al. Meta-analysis of two genome-wide association studies of bipolar disorder reveals important points of agreement. Mol Psychiatry 2008; 13: 466–467.

Ferreira MA, O’Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 1056–1058.

Cichon S, Mühleisen TW, Degenhardt FA, Mattheisen M, Miro X, Strohmaier J et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic variation in neurocan as a susceptibility factor for bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 88: 372–381.

Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 2009; 460: 748–752.

Zandi PP, Badner JA, Steele J, Willour VL, Miao K, MacKinnon DF et al. Genome-wide linkage scan of 98 bipolar pedigrees and analysis of clinical covariates. Mol Psychiatry 2007; 12: 630–639.

Park N, Juo SH, Cheng R, Liu J, Loth JE, Lilliston B et al. Linkage analysis of psychosis in bipolar pedigrees suggests novel putative loci for bipolar disorder and shared susceptibility with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 1091–1099.

Potash JB, Zandi PP, Willour VL, Lan TH, Huo Y, Avramopoulos D et al. Suggestive linkage to chromosomal regions 13q31 and 22q12 in families with psychotic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 680–686.

Kerner B, Brugman DL, Freimer NB . Evidence of linkage to psychosis on chromosome 5q33–34 in pedigrees ascertained for bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2007; 144: 74–78.

Joo EJ, Greenwood TA, Schork N, McKinney RA, Sadovnick AD, Remick RA et al. Suggestive evidence for linkage of ADHD features in bipolar disorder to chromosome 10p14. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010; 153: 260–268.

Green EK, Raybould R, Macgregor S, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Hyde S et al. Operation of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene, neuregulin 1, across traditional diagnostic boundaries to increase risk for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 642–648.

De Pradier M, Gorwood P, Beaufils B, Ades J, Dubertret C . Influence of the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism, cannabis and childhood sexual abuse on phenotype of bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. Eur Psychiatry 2010; 25: 323–327.

Benedetti F, Dallaspezia S, Colombo C, Lorenzi C, Pirovano A, Smeraldi E . Association between catechol-O-methyltransferase Val(108/158)Met polymorphism and psychotic features of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2010; 125: 341–344.

Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski PM, Schumacher J, Kassem L, Deschner M et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 2101–2108.

Priebe L, Degenhardt FA, Herms S, Haenisch B, Mattheisen M, Nieratschker V et al. Genome-wide survey implicates the influence of copy number variants (CNVs) in the development of early-onset bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2012; 17: 421–432.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, JBW Williams . Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, USA, 1998.

McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I . A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness. Development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48: 764–770.

Smith EN, Bloss CS, Badner JA, Barrett T, Belmonte PL, Berrettini W et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in European American and African American individuals. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14: 755–763.

Nurnberger JI, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 849–859.

Dziuban CD, Shirkey EC . When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol Bull 1974; 81: 358–361.

Yeomans KA, Golder PA . The Guttman-Kaiser criterion as a predictor of the number of common factors. J R Stat Soc Ser D 1982; 31: 221–229.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 559–575.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14 000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature 2007; 447: 661–678.

International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature 2005; 43: 71299–71320.

Tabachnick B, Fidell L . Using Multivariate Statistics. HarperCollins College Publishers: New York, USA, 1996.

Roncero I, Alvarez E, Chowen JA, Sanz C, Rabano A, Vazquez P et al. Expression of glucose transporter isoform GLUT-2 and glucokinase genes in human brain. J Neurochem 2004; 88: 1203–1210.

Brandish PE, Su M, Holder DJ, Hodor P, Szumiloski J, Kleinhanz RR et al. Regulation of gene expression by lithium and depletion of inositol in slices of adult rat cortex. Neuron 2005; 45: 861–872.

Boudry G, Cheeseman CI, Perdue MH . Psychological stress impairs Na+-dependent glucose absorption and increases GLUT2 expression in the rat jejunal brush-border membrane. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007; 292: 862–867.

Potkin SG, Turner JA, Guffanti G, Lakatos A, Fallon JH, Nguyen DD et al. A genome-wide association study of schizophrenia using brain activation as a quantitative phenotype. Schizophr Bull 2009; 35: 96–108.

Davidson RJ, Irwin W . The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends Cogn Sci 1999; 3: 11–21.

Ritchey M, Dolcos F, Eddington KM, Strauman TJ, Cabeza R . Neural correlates of emotional processing in depression: Changes with cognitive behavioral therapy and predictors of treatment response. J Psychiatr Res 2011; 45: 577–587.

Hamilton JP, Etkin A, Furman DJ, Lemus MG, Johnson RF, Gotlib IH . Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of baseline activation and neural response data. Am J Psychiatry 2012 doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071105.

Hulvershorn LA, Karne H, Gunn AD, Hartwick SL, Wang Y, Hummer TA et al. Neural activation during facial emotion processing in unmedicated bipolar depression, euthymia, and mania. Biol Psychiatry 2012; 71: 603–610.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the patients who participated in this study. We also thank the probands from the community-based cohorts of PopGen, KORA and the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study. This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the context of the National Genome Research Network plus (NGFNplus) and the MooDS-Net (Grant 01GS08144 to SC and MMN; Grant 01GS08147 to MR). MR was also supported by the seventh framework program of the European Union (ADAMS project, HEALTH-F4-2009-242257). MMN also received support from the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung. The KORA research platform was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Center Munich, the German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the BMBF and by the State of Bavaria. The KORA research was supported by the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC Health) as part of LMUinnovativ. The Heinz Nixdorf Recall cohort was established with the support of the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation.

Author contributions

SC, MMN, TGS and MR initiated the study; SC, SM, MMN, TGS and MR contributed to the study design; MR, TGS, JS, BMM and BiGS recruited the patients and assigned the diagnoses; RB, SM and FJM compiled the clinical data; TWM, BMM and FD prepared the DNA and performed the genotyping; SM, MS, JF, RB and MM performed the statistical analyses; EV, SC, JT, SM, MMN, TGS and MR analyzed and interpreted the data; SC, SM, MMN, TGS and MR coordinated the work. CS, SC, SM, MMN, TGS and MR prepared the manuscript, with feedback from the other authors. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

A full list of authors is provided in the Appendix.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Appendix

Appendix

Members of the Bipolar Disorder Genome Study (BiGS) Consortium

John R Kelsoe1,2, Tiffany A Greenwood1, Caroline M Nievergelt1, Thomas B Barrett1, Rebecca McKinney1, Paul D Shilling1, Nicholas J Schork3-5, Erin N Smith3,4, Cinnamon S Bloss3,5, John Nurnberger6, Howard J Edenberg7,8, Tatiana Foroud8, Daniel L Koller6, Elliot S Gershon9, Chun-Yu Liu9, Judith A Badner9, William Scheftner10, William B Lawson11, Evaristus A Nwulia11, Maria Hipolito11, William Coryell12, John Rice13, William Byerley14, Francis McMahon15, David TW Chen15, Thomas G Schulze15,16, Wade Berrettini17, James B Potash18,19, Peter P Zandi18, Pamela B Mahon18, Melvin McInnis20, David Craig21, Szabolcs Szelinger21

1 Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego; 2 Department of Psychiatry, VA San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, CA, USA; 3 Scripps Genomic Medicine, Scripps Translational Science Institute, and 4 Department of Molecular and Experimental Medicine, The Scripps Research Institute, and 5 Scripps Health, La Jolla, CA, USA; 6 Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and 7 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Indiana University School of Medicine, and 8 Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA; 9 Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago, and 10 Department of Psychiatry, Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA; 11 Department of Psychiatry, Howard University, Washington, DC, USA; 12 Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA; 13 Division of Biostatistics, Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA; 14 Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA; 15 Human Genetics Branch, National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, USA; 16 Section on Psychiatric Genetics, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Georg-August-University, Göttingen, Germany; 17 Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 18 Department of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; 19 Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IO, USA; 20 Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 21 Neurogenomics Division, The Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Meier, S., Mattheisen, M., Vassos, E. et al. Genome-wide significant association between a ‘negative mood delusions’ dimension in bipolar disorder and genetic variation on chromosome 3q26.1. Transl Psychiatry 2, e165 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.81

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.81

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phenotypes, mechanisms and therapeutics: insights from bipolar disorder GWAS findings

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Bipolarity and suicidal ideation in children and adolescents: a systematic review with meta-analysis

Annals of General Psychiatry (2017)