Abstract

Background:

There are limited prospective studies of fish and meat intakes with risk of endometrial cancer and findings are inconsistent.

Methods:

We studied associations between fish and meat intakes and endometrial cancer incidence in the large, prospective National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Intakes of meat mutagens 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (DiMeIQx) and benzo(a)pyrene (BaP) were also calculated. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

We observed no associations with endometrial cancer risk comparing the highest to lowest intake quintiles of red (HR=0.91, 95% CI 0.77–1.08), white (0.98, 0.83–1.17), processed meats (1.02, 0.86–1.21) and fish (1.10, 95% CI 0.93–1.29). We also found no associations between meat mutagen intakes and endometrial cancer.

Conclusion:

Our findings do not support an association between meat or fish intakes or meat mutagens and endometrial cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common incident cancer among US women, with an estimated 47 130 new cases in 2012 (National Cancer Institute, 2012). Previous studies on meat intake and endometrial cancer provide mixed results, with some suggesting a positive association (Shu et al, 1993; Goodman et al, 1997; Terry et al, 2002a; Salazar Martinez et al, 2005; Cross et al, 2007; Bravi et al, 2009) and others showing no association (Potischman et al, 1993; Zheng et al, 1995; McCann et al, 2000; Littman et al, 2001; Genkinger et al, 2012). However, the majority of these studies are retrospective, case–control studies (and thus subject to recall bias). Most studies of fish intake and endometrial cancer are also retrospective and report no relationship (Levi et al, 1993; Hirose et al, 1996; Goodman et al, 1997; Fernandez et al, 1999; Jain et al, 2000; McCann et al, 2000; Bravi et al, 2009). Limited studies suggest positive (Shu et al, 1993; Xu et al, 2006) or inverse associations (Terry et al, 2002b; Arem et al, 2012) between fish intake and endometrial cancer. Several mutagens can form during high-temperature meat cooking, including heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are also found in tobacco smoke (Voutsinas et al, 2012). Although smoking has been inversely associated with endometrial cancer (Amant et al, 2005), meat mutagens and endometrial cancer risk has not been studied.

Given these gaps in the literature, we investigated fish, meat and meat mutagen intakes with incident endometrial cancer in the large, prospective National Institutes of Health (NIH)-AARP Diet and Health Study.

Materials and methods

Study population

The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study has been previously described (Schatzkin et al, 2001). In brief, 566 398 individuals aged 50–71 years satisfactorily completed mailed questionnaires in 1995–1996. Following exclusions (males, n=339 666; proxy respondents, n=1265; baseline cancers other than non-melanoma skin cancer, n=24 715; end-stage renal disease, n=371; hysterectomy, n=81 646; menstrual periods stopped because of surgery/radiation/chemotherapy, n=2342; calorie intake >2 interquartile ranges >75th or <25th percentile on the log scale, n=1070; body mass index (BMI) <12 or >80 kg m–2, n=3951; zero person-time; n=16) an analytic cohort of 111 356 women remained, from which we identified 1486 incident endometrial cancer cases. Within 6 months of baseline questionnaire, a risk factor questionnaire (RFQ) was administered inquiring about meat preparation methods (response rate=67%). Of women who met baseline exclusion criteria, 72 796 also completed the RFQ and 966 developed endometrial cancer. The Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) approved the study.

Dietary assessment

At baseline, participants completed a 124-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ, developed at the US NCI) on usual frequency of food and beverage consumption (10 categories) and usual portion size (3 categories) over the past year. Line items were linked to the 1994–1996 US Department of Agriculture’s Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals to calculate nutrient and energy intakes (Subar et al, 2000). Separate line items questioned about fresh and processed red meats, poultry, finfish/shellfish, canned tuna and fried fish. The RFQ further queried on usual cooking method (grilled/barbequed, pan-fried, microwaved and broiled), outside and inside appearance, and doneness (well-done/very well-done and medium/rare) of meat. These line items were used in conjunction with the NCI CHARRED database to estimate values for HCAs 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (DiMeIQx), and benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), a marker for PAHs (National Cancer Institute, 2006; Cantwell et al, 2004; Sinha et al, 2005).

Case ascertainment

Endometrial cancer cases were ascertained by record linkage to 11 state cancer registries. Case ascertainment has been reported as >90% complete (Havener, 2004; Michaud et al, 2005). Our analysis included eligible cases of incident endometrial cancer diagnosed through 12/31/2006 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition, codes 54–55).

Statistical analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between meat, fish and meat mutagens with endometrial cancer were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Follow-up time was calculated from baseline questionnaire for meat/fish models and from date of RFQ for meat mutagen models. Individuals were censored at endometrial cancer diagnosis, death, emigration from study area or end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Proportionality of data were verified by graphical inspection. Multivariable models were adjusted for endometrial cancer risk factors age, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, ages at menarche, first live birth, and menopause, parity, diabetes, hormone therapy (HT) use, and oral contraceptive use. Ethnicity, family history of cancer, alcohol and coffee consumption and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were evaluated as potential covariates but were not included in final models because inclusion did not alter risk estimates. We also performed analyses stratified by smoking status (never/ever), use of HT (never/ever) and BMI (<25 or ⩾25 kg m–2) and created interaction terms between meat or fish and potential effect modifiers using the Wald test for statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two-sided.

Results

During a mean 9.3 years of follow-up, 1486 women were diagnosed with endometrial cancer.

Table 1 presents distributions of endometrial cancer risk factors across quintiles of red meat intake. Women who consumed more red meat had higher rates of obesity, lower HT usage, were more likely to be current smokers and less likely to be physically active.

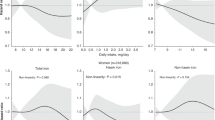

HR estimates and 95% CIs for red (0.91, 0.77–1.08), white (0.98, 0.83–1.17) and processed meat (1.02, 0.86–1.21) intakes showed no associations with endometrial cancer (Table 2). Neither total fish (HR=1.10, 95% CI 0.93–1.29) nor fried fish intakes (HR=0.99, 95% CI 0.85–1.15) were associated with risk. PhIP, MeIQx, DiMeIQx and BaP were also not associated with risk comparing extreme quintiles, although a suggested positive trend was observed for DiMeIQx intake (P=0.049).

For red meat, interactions with HT and smoking were significant (P=0.001 and P=0.049, respectively; Supplementary Table 1). Analyses stratified by HT showed no association between red meat intake and endometrial cancer among never HT users (HR=1.00, 95% CI 0.80–1.24), whereas among ever HT users the association was inverse but not significant (0.83, 0.63–1.09). In analyses stratified by smoking, higher red meat intake among ever smokers was associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer (0.77, 0.60–0.98), whereas no association was observed for never smokers (1.07, 0.84–1.36). Interaction terms between intakes of white or processed meat and fish with HT, smoking status and BMI were not significant (P-interactions>0.1).

Discussion

In this large, prospective investigation of US women, we observed no association between meat, fish or meat mutagens intakes and endometrial cancer incidence; furthermore, risk was not modified by BMI, HT or smoking status. Stratified analyses showed that the suggested protective association observed with higher red meat intake could be due to confounding, as the HRs were close to 1.00 among never smokers and never HT users.

Our findings contrast with a previous all-cancer investigation in this cohort that reported a 25% lower endometrial cancer risk comparing extreme red meat intake quintiles (P-trend=0.02; Cross et al, 2007). Discrepant findings are likely due to endometrial cancer-specific risk factors not adjusted for in the all-cancer analysis, or could be due to more cases and follow-up time in this study. A 2007 meta-analysis (Bandera et al, 2007) on meat intake and endometrial cancer risk reported a 44% increased odds of endometrial cancer comparing highest vs lowest intake categories in five ‘robust’ case–control studies (>200 cases, calorie and BMI adjustment; Potischman et al, 1993; Shu et al, 1993; Goodman et al, 1997; Littman et al, 2001; Xu et al, 2006). This association was strongest for red meat and fish intakes (59% and 88% increased risks, respectively). Another case–control study (454 cases) also found a positive association between red meat intake and endometrial cancer (Bravi et al, 2009), whereas a recent cohort study (718 cases) reported no association with red or processed meat (Genkinger et al, 2012).

Of the studies on fish in the meta-analysis, most found no association (Levi et al, 1993; Hirose et al, 1996; Goodman et al, 1997; Fernandez et al, 1999; Jain et al, 2000; McCann et al, 2000; Bravi et al, 2009), while two Chinese studies reported higher risk with more fresh-water fish consumption (Shu et al, 1993; Xu et al, 2006). Two other studies suggested inverse associations between fatty fish consumption and endometrial cancer (Terry et al, 2002b; Arem et al, 2012). However, all but one of the reviewed studies (Jain et al, 2000) were case–control design where recall bias is a concern.

Our large sample size, prospective data and wide range of dietary intakes are strengths that provide a more definite conclusion about the lack of association between meat/fish intakes and endometrial cancer. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess meat mutagens and endometrial cancer. An additional strength in the study size is the ability to assess effect modification and to restrict analyses to never smokers and never HT users. Limitations include the single dietary assessment and differences in FFQs between studies, making comparison of intake quantity difficult. Also, we lacked data on specific types of meat (lean vs non-lean) or fish (fatty vs non-fatty), which may have different associations with risk.

Overall, we found no association between meat intake and endometrial cancer. Future research could investigate specific types of meat or fish not detailed in this study.

Change history

06 August 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I (2005) Endometrial cancer. Lancet 366 (9484): 491–505

Arem H, Neuhouser ML, Irwin ML, Cartmel B, Lu L, Risch H, Mayne ST, Yu H (2012) Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid intakes and endometrial cancer risk in a population-based case-control study. Eur J Nutr 52 (3): 1251–1260

Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Moore DF, Gifkins DM, McCullough ML (2007) Consumption of animal foods and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 18 (9): 967–988

Bravi F, Scotti L, Bosetti C, Zucchetto A, Talamini R, Montella M, Greggi S, Pelucchi C, Negri E, Franceschi S (2009) Food groups and endometrial cancer risk: a case-control study from Italy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200 (3): 293 e1-293. e7

Cantwell M, Mittl B, Curtin J, Carroll R, Potischman N, Caporaso N, Sinha R (2004) Relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire with a meat-cooking and heterocyclic amine module. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 13 (2): 293–298

Cross AJ, Leitzmann MF, Gail MH, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Sinha R (2007) A prospective study of red and processed meat intake in relation to cancer risk. PLoS Med 4 (12): e325

Fernandez E, Chatenoud L, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S (1999) Fish consumption and cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr 70 (1): 85–90

Genkinger JM, Friberg E, Goldbohm RA, Wolk A (2012) Long-term dietary heme iron and red meat intake in relation to endometrial cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr 96 (4): 848–854

Goodman MT, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Lyu LC, McDuffie K, Liu LQ, Kolonel LN (1997) Diet, body size, physical activity, and the risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer Res 57 (22): 5077–5085

Havener L (2004) Standards for Cancer Registries Volume III: Standards for Completeness, Quality, Analysis, and Management of Data. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries: Springfield, IL, USA

Hirose K, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Inoue M, Kuroishi T, Kuzuya K, Nakamura S, Tokudome S (1996) Subsite (cervix/endometrium)-specific risk and protective factors in uterus cancer. Cancer Sci 87 (9): 1001–1009

Jain MG, Howe GR, Rohan TE (2000) Nutritional factors and endometrial cancer in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Control 7 (3): 288–296

Levi F, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Negri E (1993) Dietary factors and the risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer 71 (11): 3575–3581

Littman A, Beresford S, White E (2001) The association of dietary fat and plant foods with endometrial cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control 12 (8): 691–702

McCann SE, Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, Brasure JR, Swanson MK, Graham S (2000) Diet in the epidemiology of endometrial cancer in western New York (United States). Cancer Causes Control 11 (10): 965–974

Michaud D, Midthune D, Hermansen S, Leitzmann M, Harlan L, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A (2005) Comparison of cancer registry case ascertainment with SEER estimates and self-reporting in a subset of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Registry Manage 32 (2): 70–75

National Cancer Institute (2006) CHARRED: computerized heterocyclic amines database resource for research in the epidemiologic of disease. Available from: http://dceg.cancer.gov/tools/design/charred

National Cancer Institute (2012) Endometrial cancer. In What You Need to Know About Cancer of the Uterus Vol. 2012. Bethesda, MD, USA

Potischman N, Swanson CA, Brinton LA, McAdams M, Barrett RJ, Berman ML, Mortel R, Twiggs LB, Wilbanks GD, Hoover RN (1993) Dietary associations in a case-control study of endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control 4 (3): 239–250

Salazar Martinez E, Lazcano Ponce E, Sanchez Zamorano LM, Gonzalez Lira G, Escudero De Los Rios P, Hernandez Avila M (2005) Dietary factors and endometrial cancer risk. Results of a caseñcontrol study in Mexico. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15 (5): 938–945

Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, Hurwitz PE, Coyle L, Schussler N, Michaud DS, Freedman LS, Brown CC, Midthune D, Kipnis V (2001) Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions: the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 154 (12): 1119–1125

Shu XO, Zheng W, Potischman N, Brinton LA, Hatch MC, Gao Y-T, Fraumeni JF (1993) A population-based case-control study of dietary factors and endometrial cancer in Shanghai, People's Republic of China. Am J Epidemiol 137 (2): 155–165

Sinha R, Cross A, Curtin J, Zimmerman T, McNutt S, Risch A, Holden J (2005) Development of a food frequency questionnaire module and databases for compounds in cooked and processed meats. Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (7): 648–655

Subar AF, Midthune D, Kulldorff M, Brown CC, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A (2000) Evaluation of alternative approaches to assign nutrient values to food groups in food frequency questionnaires. Am J Epidemiol 152 (3): 279–286

Terry P, Vainio H, Wolk A, Weiderpass E (2002a) Dietary factors in relation to endometrial cancer: a nationwide case-control study in Sweden. Nutr Cancer 42 (1): 25–32

Terry P, Wolk A, Vainio H, Weiderpass E (2002b) Fatty fish consumption lowers the risk of endometrial cancer: a nationwide case-control study in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 11 (1): 143–145

Voutsinas J, Wilkens LR, Franke A, Vogt TM, Yokochi LA, Decker R, Le Marchand L (2012) Heterocyclic amine intake, smoking, cytochrome P450 1A2 and N-acetylation phenotypes, and risk of colorectal adenoma in a multiethnic population. Gut 62 (3): 416–422

Xu WH, Dai Q, Xiang YB, Zhao GM, Zheng W, Gao YT, Ruan ZX, Cheng JR, Shu XO (2006) Animal food intake and cooking methods in relation to endometrial cancer risk in Shanghai. Br J Cancer 95 (11): 1586–1592

Zheng W, Kushi LH, Potter JD, Sellers TA, Doyle TJ, Bostick RM, Folsom AR (1995) Dietary intake of energy and animal foods and endometrial cancer incidence. Am J Epidemiol 142 (4): 388

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the pre-doctoral training grant T32 CA105666. This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Cancer incidence data from the Atlanta metropolitan area were collected by the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. Cancer incidence data from California were collected by the California Department of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section. Cancer incidence data from the Detroit metropolitan area were collected by the Michigan Cancer Surveillance Program, Community Health Administration, State of Michigan. The Florida cancer incidence data used in this report were collected by the Florida Cancer Data System under contract with the Florida Department of Health. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the contractor or the Department of Health. Cancer incidence data from Louisiana were collected by the Louisiana Tumor Registry, Louisiana State University Medical Center in New Orleans. Cancer incidence data from New Jersey were collected by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey State Department of Health and Senior Services. Cancer incidence data from North Carolina were collected by the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry. Cancer incidence data from Pennsylvania were supplied by the Division of Health Statistics and Research, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. Cancer incidence data from Arizona were collected by the Arizona Cancer Registry, Division of Public Health Services, Arizona Department of Health Services. Cancer incidence data from Texas were collected by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services. Cancer incidence data from Nevada were collected by the Nevada Central Cancer Registry, Center for Health Data and Research, Bureau of Health Planning and Statistics, State Health Division, State of Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. We also thank Sigurd Hermansen and Kerry Grace Morrissey from Westat for study outcomes ascertainment and management and Leslie Carroll at Information Management Services for data support and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Arem, H., Gunter, M., Cross, A. et al. A prospective investigation of fish, meat and cooking-related carcinogens with endometrial cancer incidence. Br J Cancer 109, 756–760 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.252

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.252

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies

European Journal of Epidemiology (2021)