Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of a brief educational program on beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors related to skin cancer control among internal medicine housestaff and attending physicians.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Urban academic general medicine practice.

Participants

Internal medicine housestaff and attending physicians with continuity clinics at the practice site.

Intervention

Two 1-hour educational seminars on skin cancer control conducted jointly by a general internist and a dermatologist.

Measurements and main results

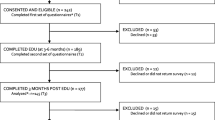

Self-reported attitudes and beliefs about skin cancer control, ability to identify and make treatment decisions on 18 skin lesions, and knowledge of skin cancer risk factors were measured by a questionnaire before and after the teaching intervention. Exit surveys of patients at moderate to high risk of skin cancer were conducted 1 month before and 1 month after the intervention to measure physician skin cancer control practices reported by patients. Eighty-two physicians completed baseline questionnaires and were enrolled in the study, 46 in the intervention group and 36 in the control group. Twenty-five physicians attended both sessions, 11 attended one, and 10 attended neither. Postintervention, the percentage of physicians feeling adequately trained increased from 35% to 47% in the control group (p=.34) and from 37% to 57% in the intervention group (p=.06). Intervention physicians had an absolute mean improvement in their risk factor identification score of 6.7%, while control physicians' mean score was unchanged (p=.06). Intervention and control physicians had similar increases in their postintervention lesion identification and managment scores. Postintervention, the mean proportion of patients per physician stating they were advised to watch their moles increased more among intervention physicians than control physicians (absolute difference of 19% vs −8%,p=.04). Other changes in behavior were not significant.

Conclusions

Although we observed a few modest intervention effects, overall this brief skin cancer education intervention did not significantly affect primary care physicians’ skin cancer control attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, or behaviors. A more intensive intervention with greater participation may be necessary to show a stronger impact on attitudes and knowledge about skin cancer control among primary care physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Marks R. An overview of skin cancers: incidence and causation. Cancer. 1995;75(suppl):607–12.

Parker SL, Tong T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1997. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47(1):5–7.

Glass AG, Hoover RN. The emerging epidemic of melanoma and squamous cell skin cancer. JAMA. 1989;262:2097–100.

Urback R. Incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Clin. 1991;9:751–5.

Koh HK. Cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:171–82.

Mackie RM, Hole D. Audit of public education campaign to encourage earlier detection of melanoma. BMJ. 1992;304:1012–5.

Rigel DS, Rivers JK, Kopf AW, et al. Dysplastic nevi: markers for increased risk for melanoma. Cancer. 1989;63:386–9.

Tristen AD, Grin CM, Kopf AW, et al. Prospective follow-up for malignant melanoma in patients with atypical-mole syndrome. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:44–8.

Dolan NC, Martin GJ, Robinson JK, Rademaker AW. Skin cancer control practices among physicians in a university general medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:515–9.

Wender RC. Barriers to effective skin cancer detection. Cancer. 1995;75S(2suppl):691–8.

American Cancer Society. 1989 survey of physicians' attitudes and practices in early cancer detection. CA Cancer J Clin. 1990;40(2):77–99.

McCarthy GM, Lamb GC, Russel TJ, Young MJ. Primary carebased dermatology practice: internists need more training. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:52–6.

Cassileth BR, Clark WH, Lusk EJ, Frederick BE, Thompson CJ, Walsh WP. How well do physicians recognize melanoma and other problem lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:555–60.

Ramsey DL, Fox AB. The ability of primary care physicians to recognize the common dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:620–2.

Geller AC, Koh HK, Miller DR, Clapp RW, Mercer MB, Lew RA. Use of health services before the diagnosis of melanoma. Implications for early detection and screening. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:154–7.

Ries LAG, Miller BA, Hankey BF, et al., eds. WEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1991: Tables and Graphs. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute: 1994. NIH publication no. 94-2789.

Rhodes AR, Weinstock MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Mihm MC, Sober AJ. Risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: a practical method of recognizing predisposed individuals. JAMA. 1987;258:3146–54.

Koh HK, Barnhill RL, Rogers GS. Melanoma. In: Arndt K, LeBoit R, Robinson JK, Whitcomb R, eds. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co.: 1996:1576–9.

Weinstock HA. Assessment of sun sensitivity by questionnaire: validity of items and formulation of a prediction rule. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:547–52.

Headrick LA, Speroff T, Pelecanos HI, Cebul RD. Efforts to improve compliance with the National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2490–6.

Browner WS, Baron RB, Solkowitz S, Adler LJ, Gullion DS. Physician management of hypercholesterolemia: a randomized trial of continuing medical education. West J Med. 1994;161(6):572–8.

Cohen SJ, Halvorson HW, Gosselink CA. Changing physician behavior to improve disease prevention. Prev Med. 1994;23(3):284–91.

McKinney WP, Barnas GP. Influenza immunization in the elderly: knowledge and attitudes do not explain physician behavior. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(10):1422–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supported in part by the Robert H. Lurie Cancer Center of Northwestern University. Dr. Dolan is a recipient of the American Cancer Society Career Development Award for Primary Care Physicians.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolan, N.C., Ng, J.S., Martin, G.J. et al. Effectiveness of a skin cancer control educational intervention for internal medicine housestaff and attending physicians. J GEN INTERN MED 12, 531–536 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07106.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07106.x