-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

LD Edmunds, Parents' perceptions of health professionals' responses when seeking help for their overweight children, Family Practice, Volume 22, Issue 3, June 2005, Pages 287–292, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmh729

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. Childhood obesity continues to worsen and so more parents of overweight children are likely to seek help from health professionals. Attitudes and practices of primary care personnel have been sought about adult obesity, but rarely about overweight children. Parents' views in this respect have not been explored. This paper addresses that omission.

Objectives. The aim was to explore parents' perceptions of help-seeking experiences with health professionals.

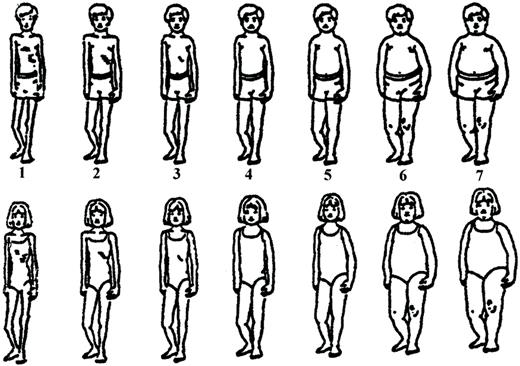

Methods. This study was a qualitative investigation with parents, conducted in central and south-west England using semi-structured interviews and body shapes used as prompts. Sampling was purposive to ensure an age range of children (4–15 years). Parents of 40 children with concerns about their child's weight were interviewed in their homes. Analysis was thematic and iterative.

Results. Parents went through a complex process of monitoring and self-help approaches before seeking professional help. The responses they received from GPs included: being sympathetic, offering tests and further referrals, general advice which parents were already following, mothers were blamed, or dismissed as “making a fuss”, and many showed a lack of interest. Health visitors offered practical advice and paediatric dietitians were very supportive. Experiences with community dietitians were less constructive.

Conclusion. Professional responses ranged from positive, but not very helpful, to negative and dismissive. Health professionals may benefit from a better understanding of parents' plight and childhood obesity in general. This in turn may improve their attitudes and practices and encourage parents to seek help at an earlier stage of their child's overweight.

Edmunds LD. Parents' perceptions of health professionals' responses when seeking help for their overweight children. Family Practice 2005; 22: 287–292.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity in children continues to increase in developed and developing countries.1,2 The International Obesity Task Force review of obesity in children and young people has documented the rise in prevalence of overweight and obesity from 102 countries using their own conservative definitions. Their latest estimates of overweight and obesity in school age children from different global areas were: 32% were overweight in the Americas, including 8% who were obese; the corresponding prevalence was 20% and 4% in Europe; 16% and 6% in the Near and Middle East; and 5% and 1% in the Asia-Pacific region.2

Health professionals tend to see children when their weight problem is well established and earlier intervention opportunities have been missed. Both primary and secondary prevention strategies are important for child weight management, particularly as treatment effects are limited.3 In children, lifestyle behaviours which contribute to and perpetuate obesity may be more open to change. Intervening with families is significant as parents can be effective agents of change within the shared environment, and where other family members may have weight problems.4,5 Therefore, it may be beneficial for families with overweight children to seek professional help when children are less overweight. However, health professionals need to take account of the family circumstances and the broader social/environmental contexts which undermine weight management. Establishing positive relationships between parents (and child) and health professionals is likely to be a critical feature of successful child weight management. This raises an important issue: are health professionals contributing to parental delay in seeking help because of their attitudes towards families with overweight and obese children?

There have been a number of surveys addressing health professionals' attitudes and practices towards adult obesity.3,6–11 However, health professionals' attitudes and practices towards childhood weight management are limited,12 although there have been several advisory documents published recently in Australia,13 in the UK4,14,15 and in the US where an entire supplement of Pediatrics was devoted to management in the US system. GPs are known to be a frequently used source of information about weight management, making them an important link in the weight management chain.3 Causes of weight gain may be similar in children, i.e. a positive energy balance. However, attitudes towards children are likely to be very different compared with adults and their treatment would be better suited to family-based approaches,4,5 particularly given the sensitive nature of overweight.

To date, parental perceptions of professional advice have rarely been sought. Therefore, the aim of this study was to document the experiences of parents seeking help from health professionals in England for their overweight children, so that practice may be improved.

Methods

In-depth interviews were chosen as the most appropriate method for exploring the very complex and extremely sensitive subject of childhood obesity. Interviews allowed for greater flexibility, interaction and allow novel topics to arise, so that themes could be identified. The method of constant comparison was used to refine and revise themes. This approach is underpinned by Grounded Theory which provided a framework to explore parents' experiences and their social interactions with health professionals.16 Data were collected and analysed concurrently and the emergent themes detailed below.

Recruitment and sample

Two areas of England were selected to increase the likelihood of participation as the social stigma associated with childhood obesity was a major barrier and to finding a range of parental experiences with children of each gender, from different social backgrounds and with access to different health care provision. Parents of school age children (4–15 years) who had concerns about their children's weight were included. Within a reasonably homogenous sample ‘data saturation’ is achieved within 40 interviews17 and so parents of 40 children (20 in each area) were recruited into the study.

Initial attempts to recruit volunteers were through health professionals, posters in primary care settings and advertising in local papers. Recruitment through weight loss groups was added subsequently to improve response rates. Parents were self-selecting and those interested in taking part received an information sheet and a reply slip through health professionals or at weight loss groups, or were invited to telephone the author for more information when responding to advertisements. Parents were recruited via the following sources: 21 from advertisements, nine (out of 22 who were informed) from paediatric dietitians, nine from slimming groups and one from a poster in their primary care setting. Thirty seven of the children's parents were white and the others were of Afro-Caribbean extraction, Indian and Iranian. Children came from a range of different socio-economic backgrounds, 23 of whom were girls. The age and size of the children can be seen in Table 1.

Age, sex and shape of children

| Shape . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4/5 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ▴ | • | ▴ | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||||

| 5/6 | • | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | ▴ | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | • | • | ▴▴ | •• | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6/7 | • | ▴ | •▴ | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | ▴▴ | ▴ | •• | • | • | ▴ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| Shape . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4/5 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ▴ | • | ▴ | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||||

| 5/6 | • | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | ▴ | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | • | • | ▴▴ | •• | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6/7 | • | ▴ | •▴ | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | ▴▴ | ▴ | •• | • | • | ▴ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||

Girl = •; boy = ▴.

Age, sex and shape of children

| Shape . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4/5 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ▴ | • | ▴ | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||||

| 5/6 | • | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | ▴ | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | • | • | ▴▴ | •• | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6/7 | • | ▴ | •▴ | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | ▴▴ | ▴ | •• | • | • | ▴ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| Shape . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4/5 | • | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ▴ | • | ▴ | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||||

| 5/6 | • | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | ▴ | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | • | • | ▴▴ | •• | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6/7 | • | ▴ | •▴ | • | • | ▴ | ▴ | • | • | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | ▴▴ | ▴ | •• | • | • | ▴ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||||||

Girl = •; boy = ▴.

Interviews

The interview schedule was piloted and included topics such as the child's or children's weight history from pregnancy in conjunction with the body shapes18 (see Fig. 1) and photographs, together with family weight history, self-help strategies and societal interactions including experiences when seeking professional help. In all cases, parents were telephoned and the research was discussed for 20 to 35 minutes before the interview appointment was made. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the author and audio-tape recorded with the participant's written consent, in their own homes. Thirty interviews were conducted with mothers and ten with both parents present. Interviews took between 45 and 150 minutes, with most lasting around 75 minutes, and were conducted over a period of 15 months up to January 2002.

Analysis

Descriptive data were recorded documenting children's ages, the current and past shapes of the children and other family members. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy by comparing the transcript with the tape and reread several times. Higher initial categories were ‘thoughts about asking for professional help’ and ‘interactions with health professionals’, the latter was divided into a range of positive to negative subcategories. Themes were discussed with a second qualitative researcher with evidence from the data. Finally two focus groups were held, one in each area, to test the veracity of findings with participants. The sex, age and shape of the children have been used as an identifier for their respective parents' observations.

Results

All the parents had tried their own dietary and physical activity strategies to address their child's persistent weight gain before seeking professional help. When the child was approximately shape 6, parents questioned an underlying medical cause, a response that was irrespective of the child's age and sex.

When parents consulted a GP, the responses they received grouped into four main themes: helpful; unaware of how to help; dismissive; and negative. Some health professionals were empathetic and helpful, with one paediatric dietitian described as “brilliant” (girl: 9y, shape 6). The same mother remarked that a paediatric registrar was “ever so sweet, but he just didn't have a clue.” Another parent said “… my GP, who's lovely and very helpful … I couldn't fault the way she handled it” (girl: 6y, shape 6+). GPs tended to conduct blood tests when parents requested them where the child was unusual in the family or there was a family history of thyroid abnormalities, heart disease or diabetes. These parents considered they had been listened to and their concerns taken seriously.

Many parents felt that the health professionals did not know how to address the issue of childhood weight management. One parent recalled her GP openly admitting this “I don't know the answer” (girl: 15y, shape 6+). Another remembered advice from her GP for which there is equivocal evidence “it's more a case of tread very softly because you'll give her anorexia.” This may or may not be accurately remembered, but this parent would have liked a more robust response: “You can't possibly say she's got a weight problem, because you're shoving her down that road of [eating disorders] … and she's huge” (girl: 12y, shape 7). One parent considered her GP to be “really good … he will take time, but when it comes to childhood and weight he's just, I don't think he knows where he's to. He'd rather pass it to somebody who he thinks knows what they're talking about” (girl: 14y, shape 7). Some children were referred to other specialists (e.g. an endocrinologist and a plastic surgeon). However paediatricians faired less well: “Paediatricians are dealing with kids all the time but they've got nothing … they don't know what to do with overweight kids” (boy: 8y, shape 7).

These perceptions of responses are a reflection of the modest evidence-base for the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity that inform health professionals. The existing guidance recommends healthier eating, reducing sedentary behaviours and more physical activity. Also none of these children would have been classified as obese. If advice was offered, it was generally in keeping with these recommendations, but with more emphasis on dietary reduction. Parents in all cases were aware, or had already put these into practice: “everything that came home was bog standard, try to do this and not that, we do already” (boy: 12y, shape 6+). Therefore parents were disappointed or frustrated with the realisation that health professionals had little to add and so appeared not to have answers. Generally GPs were seen positively and were described as helpful, but parents went for help more with hope than expectation: “you're the doctor, give me a cure. Now I knew that wasn't gonna happen, but you always expect it don't you” (boy: 11y, shape 6).

The next theme to emerge was the dismissal of the need for help in response to parental requests. Parents recalled their GPs saying “She's lovely, she'll grow out it” (girl: 9y, shape 6), “it's not an issue” (girl: 6y, shape 6+), “he's fine, it's nothing” (boy: 10y, shape 5+), or were told “there's nothing to worry about” and so a discussed appointment with the dietitian did not materialise “ … and that's the last I heard” (girl: 9y, shape 6+). Other health professionals (a school nurse, community dietitian and two practice nurses) had offered to weigh the child on a regular basis, but no appointments were given. A school nurse was remembered saying “I wouldn't worry about her weight, not at this stage” when the child was 13 years old and shape 7. Other parents felt their dismissals were more negative: “Don't worry [GP]. He was like fobbing me off, he didn't seem concerned or nothing” (boy: 8y, shape 7), and as a result of visiting an out patient clinic “they just made you feel like you were being silly … You leave there feeling like a paranoid parent” (boy: 10y, shape 5+).

All parents had identified a potentially persistent weight problem in their children. The evidence and recommendations from an expert committee suggest that weight management needs to be instigated as early as possible. The rate of increase in childhood obesity is likely to result in more children remaining overweight and becoming obese, than their achieving normal weight with growth. These delays may be inappropriate and health professionals were missing the opportunity to effect behaviour changes before obesity is established.

The last theme covers the range of negative attitudes parents recalled encountering. Some parents were made to feel blameworthy by their GP: “you're not trying hard enough. You are doing something wrong. He should eat 700 calories a day” (boy: 12y, shape 6+); GP to mother “well you buy the food” (boy: 10y, shape 7); and by a consultant: “You're over-feeding her, you'll have to stop her intake of food … he just sat there and wasn't interested, just really wasn't interested in us” (girl: 9y, shape 6). One mother remarked on a passing comment a consultant had made when there was little opportunity for discussion: “He [the consultant] said if he lost a stone in weight it would help, almost as you're walking out the door” (boy: 15y, shape 7). Dietitians were also perceived to react inappropriately “I just couldn't believe she [the dietitian] was the person that was nominated to give us advice because … she was so negative and it made us feel so inadequate in the end. It was awful” (girl: 7y, shape 6), and “I can understand what she was saying but she was just so negative about what I was doing” (boy: 14y, shape 5+). One mother had taken her daughter to the dietitian “an official,” who mother recollected saying to her daughter “You're gonna be big, so you might as well enjoy it”. The daughter's response was “She [the dietitian] says that I'm going to be big, so I might as well eat” (girl: 12y, shape 7).

Within this theme, some GPs made mothers in particular, feel that their level of concern was unwarranted: “I said I was concerned … it really was like water off a duck's back. It's ‘Oh well, this is a very difficult age group and it's puppy fat and if you really are concerned contact the health visitor’” (girl: 11y, shape 7). Two other mothers recalled similar experiences: “these things all correct themselves [GP] But it is the traditional attitude of GPs that think you're being too fussy” (boy: 11y, shape 6) and “I've found the GP here not very helpful at all. When you get worried they think there is something wrong with your mind” (girl: 9y, shape 6+).

Weight management tends to be viewed as unrewarding by health professionals and as a lifestyle issue rather than a medical one,3 although the evidence is accumulating for health consequences of obesity in children.2 Not all parents were offered a dietitian and other doctors in the primary care setting were often more proactive than their regular GP. In some cases parents sought a medical reason for the prospect of a medical remedy to resolve their child's weight problem. The general lack of practical help–“We didn't really get any help or advice from anywhere” (boy: 5y, shape 5, formally shape 6)–left parents disappointed: “I feel like I'm wandering around in the dark on my own” (girl: 14y, shape 7).

Discussion

This study reflects the views of self-selecting parents who acknowledged their child was overweight and who were willing to take part in this type of research. Their recollection of health professional statements may not be totally accurate, although their emotions associated with them were. Their views may or may not reflect those of parents with overweight children generally. However, their responses revealed a consistency of experiences, both in how they coped with their children and at what point they sought professional help. The concern about medical implications began to take hold at shape 6. This approximates to the 85th centile in the 1990 BMI growth charts.19 Similar concerns were noted at this shape in another interview-based study conducted with 100 adults who were overweight but not yet obese. Issues about overweight children was not the focus of that study and none of the adults had any overweight children themselves, but ad hoc comments (56% of those interviewed) volunteered that they would become concerned and seek professional help at shape 6.20

The perceived responses from health professionals were varied and were likely to be reflecting two factors: the social stigma attached to being overweight; and the lack of a solid evidence base for treatment in primary and secondary care. In the survey of health professionals' attitudes and practices towards paediatric obesity, lack of competence and feeling uncomfortable were revealed as issues.12 Despite the increasing numbers of overweight and obese people, the stigma if anything appears to be getting worse.21 If health professionals believe that parents are solely responsible for their child's body status without acknowledging the environmental changes encouraging weight gain, it is understandable that some of their reactions lack sympathy.

The help that parents experienced e.g. to eat healthily and to do more exercise, or undertaking ‘tests’ that were all negative in these children, became a source of frustration and/or resignation for parents and health professionals alike. Childhood obesity is extremely complex and two systematic reviews of prevention and treatment interventions have concluded that there are few good quality studies and so there is a lack of clear evidence, but reductions in sedentary behaviours,22,23 parental involvement and behavioural therapy may be beneficial.23 Without firm advice to inform primary care and only a very few specialist programmes to which children can be referred, the vast majority of overweight and obese children are unlikely to receive any effective support.

The most successful child weight management (gaining minimal weight) occurred where the health professionals were interested and positive: that is an empathetic GP and a paediatric dietitian. These parents were appreciative of efforts to help their children. However even where parents had access to these health professionals, they found a reliance on dietary restriction alone was increasingly problematic and thought that help with physical activity and support for continued motivation would also have been beneficial. None of the parents were offered help with physical activity or any psychological aspects even though the evidence identifies these as useful strategies and are recommended.24

In summary, parents were positive about health professionals generally, but encountered a variety of responses when seeking child weight management help. This range of responses may be due to, for example, not wanting to cause further distress to either parent or child, or a lack of not knowing how to help. There also appeared to be a tendency to blame the parent and to see weight as an individual responsibility. Further research is needed to improve child and adolescent weight management and with health professionals to clarify their understanding of all the issues involved. There would appear to be a need for guidance and training to help health professional practice when dealing with childhood obesity.

Declaration

Funding: South East Region NHS Executive Research and Development Fund, Grant No. SEO 151.

Ethical approval: approval was granted by the Applied Qualitative Research Ethics Committee in Oxford (AQREC No. A00.020) and by the South West Local Research Ethics Committee (Study No. 2000/4/53s).

Conflicts of interest: none.

Thanks to all the parents who took part and to the health professionals whose help was invaluable, and to Rosemary Conley Slimming Clubs and Slimming World for their support.

References

Ebbeling C, Pawlak D, Ludwig D. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure.

Lobstein T, Bauer L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: A crisis in public health.

Gibson P, Edmunds L, Haslam DW, Poskitt E. An approach to weight management in children and adolescents (2–18 years) in primary care.

Edmunds L, Waters E, Elliot EJ. Evidence based management of childhood obesity.

Campbell K, Engel H, Timperio A, Cooper C, Crawford D. Obesity management: Australian General Practitioners' attitudes and practices.

Cade J, O'Connell. Management of weight problems and obesity: knowledge, attitudes and current practice of general practitioners.

Harvey EL, Hill AJ, Health professionals' views of overweight people and smokers.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson R, Allison DB, Kessler A. Primary care physicians attitudes about obesity and its treatment.

Harvey EL, Glenny A, Kirk SF, Summerbell CD. Improving health professionals' management and the organisation of care for overweight and obese people (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library Issue 1. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons;

Jelalian E, Boergers J, Alday CS, Frank R. Survey of physician attitudes and practices related to pediatric obesity.

National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity. http://www.obesityguidelines.gov.au/

SIGN guidelines: Management of obesity in children and young people. http://www.show.scot.nhs.uk/sign/guidelines/published/index.html

The management of obesity and overweight: An analysis of reviews of diet, physical activity and behavioural approaches. London: HDA;

Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds). Strategies of Qualitative Enquiry. London: Sage;

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data.

Stunkard AJ, Sorensen TI, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. In Kely SS, Rowland LP, Sidman RL, Matthysse SW (eds). Genetics of neurologocal and psychiatric disorders. New York: Raven Press;

Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990.

Latner JD, Stunkard AJ. Getting worse: the stigmatisation of obese children.

Campbell K, Waters E, O'Meara S, Kelly S, Summerbell C. Interventions for preventing obesity in children (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library Issue 1. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons;

Summerbell CD, Ashton V, Campbell KJ, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Waters E. Interventions for treating obesity in children (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library Issue 1. Chichester: UK John Wiley & Sons;