-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shamagonam James, Priscilla S. Reddy, Robert A. C. Ruiter, Myra Taylor, Champaklal C. Jinabhai, Pepijn Van Empelen, Bart Van Den Borne, The effects of a systematically developed photo-novella on knowledge, attitudes, communication and behavioural intentions with respect to sexually transmitted infections among secondary school learners in South Africa, Health Promotion International, Volume 20, Issue 2, June 2005, Pages 157–165, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dah606

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A pre-post test follow-up design was used to test the effects of a systematically developed photo-novella (Laduma) on knowledge, attitudes, communication and behavioural intentions with respect to sexually transmitted infections, after a single reading by 1168 secondary school learners in South Africa. The reading resulted in an increase in knowledge on the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), change in attitude to condom use and towards people with STIs and/or HIV/AIDS, as well as increased intention to practice safe sex. Laduma did not influence communication about sexually transmitted infections and reported sexual behaviour and condom use. While print media proved to be an effective strategy to reach large numbers of youth and prepare them for adequate preventive behaviours, the study also identified the need to combine print media with other planned theory-based interventions that build confidence and skills to initiate the preventive behaviour.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections pose a serious public health problem for South Africa with about 11 million episodes being treated annually (Department of Health, South Africa, 2000). The emergence of HIV/AIDS has called for a reassessment of sexually transmitted infections as a co-factor in the transmission of HIV (Colvin, 2000). Since sexually transmitted infections play a role in the transmission of HIV and HIV alters the pattern of sexually transmitted infections (UNAIDS, 2000), their concurrent existence renders an infected individual more infective to their sexual partners (Colvin, 2000). Sexually transmitted infections and HIV share not just a biological link but a behavioural link as well; both infections are mainly transmitted through unprotected sexual activity (UNAIDS, 2000). This combined behavioural and biological link requires an integrated approach to its management with the emphasis on its prevention as well as treatment. The prevention of sexually transmitted infections requires interventions that increase knowledge and awareness, cultivate attitudes and social norms that are conducive to healthy and preventive behaviours and increases the intentions to practice such behaviours.

This study tested the hypotheses that a single reading of a print media intervention called Laduma, by secondary school learners, will lead to a change in their knowledge and behaviour regarding sexually transmitted infections and safe sex. It specifically tested for an increase in knowledge about sexually transmitted infections, more positive attitudes towards safe sexual behaviour (abstinence and use of condoms), more communication about safe sexual behaviour with partners, parents and peers, and increased intentions to safe sexual behaviours.

PRINT MEDIA IN THE CONTEXT OF HEALTH PROMOTION

Print media may be used to deliver health messages that aim to influence and reduce behaviours that place people at risk for disability and disease. Print media development that takes into account the characteristics and factors that lead to a problem and that is developed in conjunction with relevant stakeholders, including the target group, have been found to be more effective (Roter et al., 1981). This is because the emphasis is no longer solely on knowledge acquisition but on experiential education that is learner directed. This participatory approach to media development is grounded in theories of health promotion and social learning (Kok et al., 1996). These theories have re-oriented health education from being a passive process of information dissemination to one that is more action based. A participatory approach to media development also ensures inculcation of health promoting beliefs and cultural norms that are relevant to the target group. Research into cognitive psychology shows that motivation to learn increases when educational content relates to personal beliefs and experience, for example, through open-ended stories, socio-dramas or pictures depicting typical health-related situations.

METHODS

Participants and setting

The study was carried out among secondary school learners in the Midlands district of the province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) with over 2.7 million learners. The Midlands district is one of the eight regions of KZN. It has both rural and urban dwellers and a largely Zulu speaking population.

There are twenty-seven secondary schools in the Midlands district. Initially twenty schools were randomly selected to participate. Four of the schools refused due to time constraints (year end examinations). A further four were randomly selected from the remaining seven schools. Three accepted, resulting in a total of nineteen schools in the final sample. The schools were equally distributed in rural and urban areas. Two classes were randomly selected from all the grade 11 classes at each of the sampled schools. All the learners from those two classes were included in the study. This resulted in a sample size of 1168 learners at baseline. The language of instruction at all schools is English. Therefore, both the intervention (Laduma) and the questionnaires were conducted in English and grade 11 learners were selected as they have already had four years of secondary school education.

Written consent was obtained from parents and the Department of Education. The learners were invited to participate on a voluntary basis. There were no refusals from the parents and only one learner refused to participate. The Faculty of Medicine, Nelson R. Mandela Medical School, University of Natal granted ethical approval for the study.

Study design

The study design was an experimental design measuring a range of outcomes between control and intervention groups of learners over three time periods—baseline (T1), post-test three weeks after the baseline (T2) and six weeks after the post-test (T3). The sample size was estimated from an expected change of 15% on critical outcomes, such as, changes in knowledge about sexually transmitted infections, attitude towards preventive behaviours, communication with significant others about sexually transmitted infections and prevention and intentions for safe sexual practices.

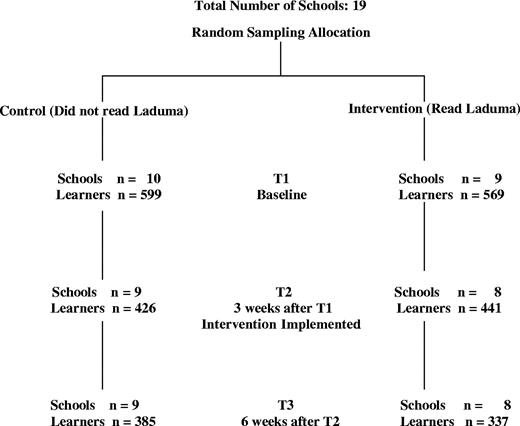

Sampling, allocation and phases of study

The schools were randomly allocated to control (did not read Laduma) and intervention (did read Laduma) groups. There were ten control and nine intervention schools (see Figure 1). All the learners from both the control and intervention schools were requested to respond to a baseline questionnaire, phase one (T1). The second phase took place three weeks later (T2). At this phase the control schools were given the same baseline questionnaire to answer again in the context of normal (not Aids-related) school lessons. The intervention schools were given Laduma to read, a break and then a questionnaire, which had baseline and Laduma-specific questions, to answer. Learners had to return Laduma and were only given a copy to keep on completion of the study. The reading of Laduma took about one hour. The third phase (T3) was carried out six weeks after T2. Learners from the control schools repeated the baseline questionnaire and learners from the intervention schools repeated their second questionnaire. At the end of the study learners from the control schools were also given a copy of Laduma so as not to disadvantage any participant. A limitation to the study was the high drop out rate of 38.2% at T3, which was attributed mainly to the impending school examinations.

Intervention

Laduma provides the reader with accurate factual information to increase their knowledge and reduce misperceptions about sexually transmitted infections, exposes them to real life situations, possible risks and solutions in a manner that they can identify with. It also aims to engender a positive attitude towards safe sexual practices and to enhance self-efficacy and adoption of skills, such as talking about sexually transmitted infections and prevention with partners, negotiating safer sexual practices and decision-making about seeking help. Factual information is provided about sexually transmitted infections, through appropriate responses by a clinic nurse and discussion amongst friends. Their responses are reinforced by a question and answer section at the back of the comic. The use of condoms as a means of protection against sexually transmitted infections is clearly demonstrated by a set of colour photographs, illustrating the correct way to use a condom. An intense discussion between the lead characters about their relationship, commitment to each other and the role of condoms as part of their sexual lives is well dramatized following an incident of unfaithfulness on the part of one of the partners. This discussion shows the need for skills that enable effective communication, decision-making and the ability to resist negative peer influences. The story in Laduma was generated through workshops with youth from Khayalitsha and Guguletu in Cape Town and Kwamashu, Inanda and Thornwood in KZN. It was expected to appeal to youth in terms of its approach to contemporary sexual practices, its portrayal of characters and the views depicted both for and against safer sexual practices. Laduma is one of few print media AIDS education interventions that was developed systematically in Africa and therefore warranted being evaluated.

Study instrument and dependent measures

A questionnaire was used to collect data and was pre-tested among sixty learners from a secondary school in the research area to ensure construct and face validity.

Most questions were closed ended with yes (1), no (−1) and unsure (0) responses. The questionnaire was individually filled in by learners and was supervised by a fieldworker and researcher during a normal class lesson. Learners were given as much time as they needed to complete the questionnaire to allow for individual abilities. Time to complete the questionnaire varied between 30 and 50 min.

Knowledge. Knowledge regarding the spread of sexually transmitted infections was measured by four items (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.60) and knowledge about the causes of sexually transmitted infections by three items (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.53).

Attitudes. Learners' attitude to condom use was measured with seven items, which were combined in a moderate reliable index (Cronbach's alpha = 0.57).

Attitude towards people (friends) infected with sexually transmitted infections or HIV/AIDS was measured through six items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.70).

Communication about sexually transmitted infections. Three groups of five items each asked pupils whether they communicate about sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS and about prevention with: their parents, friends and boy or girlfriend. Within these three groups, items were combined to create adequately reliable scales measuring communication with parents (Cronbach's alpha = 0.77), communication with friends (Cronbach's alpha = 0.65) and communication with girlfriend/boyfriend (Cronbach's alpha = 0.68).

Sexual behaviour. Sexual behaviour was measured through one item asking if one had sex during a specified period prior to the survey. Condom use was measured by asking those who had sex during the specified period if they used a condom every time they had sex, sometimes or not at all.

Intention to use condoms in the future. Intention to use condoms in the future was measured only at T3 through one self-report variable: what will your choice be for the next year? Answer alternatives were not to have sex, to have sex with a condom, to have sex without a condom.

Data analysis

As the data were organized at two levels (students within schools) and assignment of subjects to experimental and control group was done at school level, a linear mixed model data analysis procedure (SPSS 12.0) was applied with the interval level dependent variables (knowledge, attitudes, communication). To identify intervention effects at student level, predictors at student as well as school level were included in repeated measurement analyses. In the analyses different prediction models were fitted and choices were made for the best fitting models. For each of the analyses groups (experimental-control), gender and repeated measures (T1, T2, T3) were included as fixed factors and language as a covariate. Hierarchical logistic regression analysis was used in the case of dichotomous variables (having had sex, condom use and intention to use condoms). Possible interaction terms were included at the second step, and removed again from the model in case of non-significant contribution to the prediction of the dependent variable.

RESULTS

Dropout and demographic profile

Of the 1168 learners that filled in the questionnaire at T1, 18.6% failed to fill in the questionnaires at both T2 and T3. No difference in drop out between intervention group and the control group was found.

The demographic profile of the learners is presented in Table 1. Tests of independence revealed that both the distribution of boys and girls and the distribution of first language (English versus Zulu) differed for the intervention and control group, χ2 (1, n = 1164) = 8.30, p < 0.05, and χ2 (1, n = 1152) = 20.24, p < 0.001, respectively, and were therefore controlled for in testing the effects of the intervention.

Socio-demographic profile of secondary school learners

| Variables . | Control group . | . | . | Intervention group . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Male . | Female . | Total . | Male . | Female . | Total . | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–18 | 199 (33.2%) | 187 (31.2%) | 386 (64.4%) | 148 (26.1%) | 233 (40.9%) | 381 (67.0%) | ||||||

| 19–21 | 92 (15.4%) | 91 (15.2%) | 183 (30.6%) | 85 (14.9%) | 77 (13.5%) | 162 (28.5%) | ||||||

| >22 | 12 (2.0%) | 15 (2.5) | 27 (4.5%) | 6 (1.1%) | 13 (2.3%) | 19 (3.3%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 303 (50.6%) | 293 (48.9%) | 599 (100%) | 239 (42.0%) | 323 (56.8%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Home language | ||||||||||||

| English | 111 (18.8%) | 69 (11.5) | 180 (30.1%) | 53 (9,3%) | 54 (9.5%) | 107 (18.8%) | ||||||

| Zulu | 186 (31.1%) | 222 (37.1%) | 408 (68.1%) | 184 (32,3%) | 268 (47.1%) | 452 (79.4%) | ||||||

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0,2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | |||||||

| Unknown | 9 (1.5) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 299 (49.9%) | 291 (48.6%) | 599 (100%) | 238 (41.8%) | 324 (57.0%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Variables . | Control group . | . | . | Intervention group . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Male . | Female . | Total . | Male . | Female . | Total . | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–18 | 199 (33.2%) | 187 (31.2%) | 386 (64.4%) | 148 (26.1%) | 233 (40.9%) | 381 (67.0%) | ||||||

| 19–21 | 92 (15.4%) | 91 (15.2%) | 183 (30.6%) | 85 (14.9%) | 77 (13.5%) | 162 (28.5%) | ||||||

| >22 | 12 (2.0%) | 15 (2.5) | 27 (4.5%) | 6 (1.1%) | 13 (2.3%) | 19 (3.3%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 303 (50.6%) | 293 (48.9%) | 599 (100%) | 239 (42.0%) | 323 (56.8%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Home language | ||||||||||||

| English | 111 (18.8%) | 69 (11.5) | 180 (30.1%) | 53 (9,3%) | 54 (9.5%) | 107 (18.8%) | ||||||

| Zulu | 186 (31.1%) | 222 (37.1%) | 408 (68.1%) | 184 (32,3%) | 268 (47.1%) | 452 (79.4%) | ||||||

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0,2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | |||||||

| Unknown | 9 (1.5) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 299 (49.9%) | 291 (48.6%) | 599 (100%) | 238 (41.8%) | 324 (57.0%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

n=1168

Socio-demographic profile of secondary school learners

| Variables . | Control group . | . | . | Intervention group . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Male . | Female . | Total . | Male . | Female . | Total . | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–18 | 199 (33.2%) | 187 (31.2%) | 386 (64.4%) | 148 (26.1%) | 233 (40.9%) | 381 (67.0%) | ||||||

| 19–21 | 92 (15.4%) | 91 (15.2%) | 183 (30.6%) | 85 (14.9%) | 77 (13.5%) | 162 (28.5%) | ||||||

| >22 | 12 (2.0%) | 15 (2.5) | 27 (4.5%) | 6 (1.1%) | 13 (2.3%) | 19 (3.3%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 303 (50.6%) | 293 (48.9%) | 599 (100%) | 239 (42.0%) | 323 (56.8%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Home language | ||||||||||||

| English | 111 (18.8%) | 69 (11.5) | 180 (30.1%) | 53 (9,3%) | 54 (9.5%) | 107 (18.8%) | ||||||

| Zulu | 186 (31.1%) | 222 (37.1%) | 408 (68.1%) | 184 (32,3%) | 268 (47.1%) | 452 (79.4%) | ||||||

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0,2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | |||||||

| Unknown | 9 (1.5) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 299 (49.9%) | 291 (48.6%) | 599 (100%) | 238 (41.8%) | 324 (57.0%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Variables . | Control group . | . | . | Intervention group . | . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | Male . | Female . | Total . | Male . | Female . | Total . | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 15–18 | 199 (33.2%) | 187 (31.2%) | 386 (64.4%) | 148 (26.1%) | 233 (40.9%) | 381 (67.0%) | ||||||

| 19–21 | 92 (15.4%) | 91 (15.2%) | 183 (30.6%) | 85 (14.9%) | 77 (13.5%) | 162 (28.5%) | ||||||

| >22 | 12 (2.0%) | 15 (2.5) | 27 (4.5%) | 6 (1.1%) | 13 (2.3%) | 19 (3.3%) | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 303 (50.6%) | 293 (48.9%) | 599 (100%) | 239 (42.0%) | 323 (56.8%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

| Home language | ||||||||||||

| English | 111 (18.8%) | 69 (11.5) | 180 (30.1%) | 53 (9,3%) | 54 (9.5%) | 107 (18.8%) | ||||||

| Zulu | 186 (31.1%) | 222 (37.1%) | 408 (68.1%) | 184 (32,3%) | 268 (47.1%) | 452 (79.4%) | ||||||

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0,2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 3 (0.2%) | |||||||

| Unknown | 9 (1.5) | 7 (1.2%) | ||||||||||

| Total | 299 (49.9%) | 291 (48.6%) | 599 (100%) | 238 (41.8%) | 324 (57.0%) | 569 (100%) | ||||||

n=1168

Impact of Laduma on knowledge, attitude and communication

In testing the impact of Laduma on knowledge, attitude and communication, the most parsimonious effect model for all these dependent variables included Gender, Group (control versus intervention) and Time (T1 versus T2 versus T3) as fixed factors, language (Zulu versus English) as a covariate, school (2nd level) as a random intercept, and ‘Unstructured’ as repeated covariance type. The mean scores within the control group and intervention group at the three measurements and the F-values for the fixed effects resulting from the linear mixed model analyses are presented in Table 2. Difference between mean scores at T1, T2 and T3 within both the control group and intervention group were tested by using pairwise comparisons within the linear mixed models analyses. These analyses were performed separately for males and females, in case of a three-way interaction effect.

Mean scores and F-values resulting from separate 2 (Group) × 2 (Gender) × 3 (Time) linear mixed model analyses with knowledge, attitude and communication as the dependent variables

| . | Means . | . | . | . | . | . | F-values . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control group . | . | . | Experimental group . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

. | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Group . | Gender . | Time . | Gr. × Ge . | Time × Gr. . | Time × Ge. . | Time × Gr. × Ge. . | |||||||||||

| Knowl spread | 0.71a | 0.71a | 0.68a | 0.66a | 0.75b | 0.75b | 0.17 | 2.34 | 6.35 | 0.14 | 10.36*** | 0.16 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| Knowl. Cause | 0.55a | 0.65b | 0.63b | 0.54a | 0.60b | 0.64b | 0.01 | 0.10 | 10.42*** | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.23 | |||||||||||

| Att. Condom | 0.57a | 0.57a | 0.56a | 0.55a | 0.64b | 0.62b | 1.10 | 5.50* | 5.90** | 0.01 | 7.90*** | 2.20 | 1.43 | |||||||||||

| Att. PWA | 0.02 | 1.67 | 4.54 | 1.36 | 1.95 | 0.80 | 4.86** | |||||||||||||||||

| Males | 0.44a | 0.47a | 0.44a | 0.38a | 0.44a,b | 0.52b | ||||||||||||||||||

| Females | 0.46a | 0.46a | 0.49a | 0.46a | 0.51a | 0.49a | ||||||||||||||||||

| Com. Parents | −0.14a | −0.21b | −0.25b | −0.14a | −0.29b | −0.28b | 0.14 | 0.01 | 18.04*** | 13.86*** | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.37 | |||||||||||

| Com. Friends | 0.45b | 0.50b | 0.51b | 0.40a | 0.46b | 0.48b | 0.62 | 1.36 | 6.28** | 4.53* | 0.15 | 1.13 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Com. B/g friend | 0.32a | 0.31a | 0.39b | 0.30a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.09 | 0.10 | 1.88 | 7.42** | 2.90 | 0.26 | 0.86 | |||||||||||

| . | Means . | . | . | . | . | . | F-values . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control group . | . | . | Experimental group . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

. | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Group . | Gender . | Time . | Gr. × Ge . | Time × Gr. . | Time × Ge. . | Time × Gr. × Ge. . | |||||||||||

| Knowl spread | 0.71a | 0.71a | 0.68a | 0.66a | 0.75b | 0.75b | 0.17 | 2.34 | 6.35 | 0.14 | 10.36*** | 0.16 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| Knowl. Cause | 0.55a | 0.65b | 0.63b | 0.54a | 0.60b | 0.64b | 0.01 | 0.10 | 10.42*** | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.23 | |||||||||||

| Att. Condom | 0.57a | 0.57a | 0.56a | 0.55a | 0.64b | 0.62b | 1.10 | 5.50* | 5.90** | 0.01 | 7.90*** | 2.20 | 1.43 | |||||||||||

| Att. PWA | 0.02 | 1.67 | 4.54 | 1.36 | 1.95 | 0.80 | 4.86** | |||||||||||||||||

| Males | 0.44a | 0.47a | 0.44a | 0.38a | 0.44a,b | 0.52b | ||||||||||||||||||

| Females | 0.46a | 0.46a | 0.49a | 0.46a | 0.51a | 0.49a | ||||||||||||||||||

| Com. Parents | −0.14a | −0.21b | −0.25b | −0.14a | −0.29b | −0.28b | 0.14 | 0.01 | 18.04*** | 13.86*** | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.37 | |||||||||||

| Com. Friends | 0.45b | 0.50b | 0.51b | 0.40a | 0.46b | 0.48b | 0.62 | 1.36 | 6.28** | 4.53* | 0.15 | 1.13 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Com. B/g friend | 0.32a | 0.31a | 0.39b | 0.30a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.09 | 0.10 | 1.88 | 7.42** | 2.90 | 0.26 | 0.86 | |||||||||||

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Note: means within rows that do not share a common superscript differ significantly at p < 0.05.

PWA = people with STD's and HIV/AIDS.

Corrected means and F-values from linear mixed model analysis with unstructured covariance type and 2nd level (school) as random intercept.

Bold indicates the variables for which there was an interaction effect among any of the three independent variables.

Mean scores and F-values resulting from separate 2 (Group) × 2 (Gender) × 3 (Time) linear mixed model analyses with knowledge, attitude and communication as the dependent variables

| . | Means . | . | . | . | . | . | F-values . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control group . | . | . | Experimental group . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

. | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Group . | Gender . | Time . | Gr. × Ge . | Time × Gr. . | Time × Ge. . | Time × Gr. × Ge. . | |||||||||||

| Knowl spread | 0.71a | 0.71a | 0.68a | 0.66a | 0.75b | 0.75b | 0.17 | 2.34 | 6.35 | 0.14 | 10.36*** | 0.16 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| Knowl. Cause | 0.55a | 0.65b | 0.63b | 0.54a | 0.60b | 0.64b | 0.01 | 0.10 | 10.42*** | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.23 | |||||||||||

| Att. Condom | 0.57a | 0.57a | 0.56a | 0.55a | 0.64b | 0.62b | 1.10 | 5.50* | 5.90** | 0.01 | 7.90*** | 2.20 | 1.43 | |||||||||||

| Att. PWA | 0.02 | 1.67 | 4.54 | 1.36 | 1.95 | 0.80 | 4.86** | |||||||||||||||||

| Males | 0.44a | 0.47a | 0.44a | 0.38a | 0.44a,b | 0.52b | ||||||||||||||||||

| Females | 0.46a | 0.46a | 0.49a | 0.46a | 0.51a | 0.49a | ||||||||||||||||||

| Com. Parents | −0.14a | −0.21b | −0.25b | −0.14a | −0.29b | −0.28b | 0.14 | 0.01 | 18.04*** | 13.86*** | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.37 | |||||||||||

| Com. Friends | 0.45b | 0.50b | 0.51b | 0.40a | 0.46b | 0.48b | 0.62 | 1.36 | 6.28** | 4.53* | 0.15 | 1.13 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Com. B/g friend | 0.32a | 0.31a | 0.39b | 0.30a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.09 | 0.10 | 1.88 | 7.42** | 2.90 | 0.26 | 0.86 | |||||||||||

| . | Means . | . | . | . | . | . | F-values . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control group . | . | . | Experimental group . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

. | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Baseline . | Post-test 1 . | Post-test 2 . | Group . | Gender . | Time . | Gr. × Ge . | Time × Gr. . | Time × Ge. . | Time × Gr. × Ge. . | |||||||||||

| Knowl spread | 0.71a | 0.71a | 0.68a | 0.66a | 0.75b | 0.75b | 0.17 | 2.34 | 6.35 | 0.14 | 10.36*** | 0.16 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| Knowl. Cause | 0.55a | 0.65b | 0.63b | 0.54a | 0.60b | 0.64b | 0.01 | 0.10 | 10.42*** | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 1.23 | |||||||||||

| Att. Condom | 0.57a | 0.57a | 0.56a | 0.55a | 0.64b | 0.62b | 1.10 | 5.50* | 5.90** | 0.01 | 7.90*** | 2.20 | 1.43 | |||||||||||

| Att. PWA | 0.02 | 1.67 | 4.54 | 1.36 | 1.95 | 0.80 | 4.86** | |||||||||||||||||

| Males | 0.44a | 0.47a | 0.44a | 0.38a | 0.44a,b | 0.52b | ||||||||||||||||||

| Females | 0.46a | 0.46a | 0.49a | 0.46a | 0.51a | 0.49a | ||||||||||||||||||

| Com. Parents | −0.14a | −0.21b | −0.25b | −0.14a | −0.29b | −0.28b | 0.14 | 0.01 | 18.04*** | 13.86*** | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.37 | |||||||||||

| Com. Friends | 0.45b | 0.50b | 0.51b | 0.40a | 0.46b | 0.48b | 0.62 | 1.36 | 6.28** | 4.53* | 0.15 | 1.13 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Com. B/g friend | 0.32a | 0.31a | 0.39b | 0.30a | 0.34a | 0.32a | 0.09 | 0.10 | 1.88 | 7.42** | 2.90 | 0.26 | 0.86 | |||||||||||

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Note: means within rows that do not share a common superscript differ significantly at p < 0.05.

PWA = people with STD's and HIV/AIDS.

Corrected means and F-values from linear mixed model analysis with unstructured covariance type and 2nd level (school) as random intercept.

Bold indicates the variables for which there was an interaction effect among any of the three independent variables.

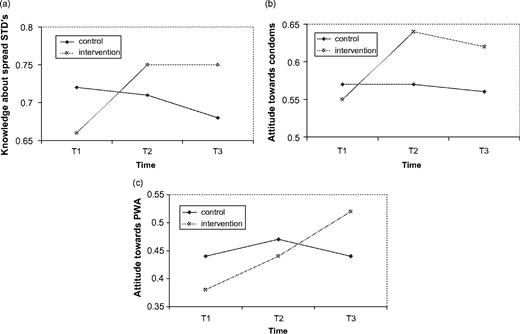

Knowledge about spread of sexually transmitted infections. A detailed analyses of the significant interaction effect in the linear mixed model analysis of Group and Time on knowledge about spread of sexually transmitted infections revealed that the knowledge levels of the intervention group and the control group did not differ at baseline. In accordance with our hypothesis, an effect of group was found both at T2 (p < 0.01) and at T3 (p < 0.001). At both T2 and T3, participants in the intervention group had more knowledge about the spread of sexually transmitted infections than participants in the control group (see Figure 2a). Analyses of the differences between mean scores within the intervention group showed that the knowledge about spread of sexually transmitted infections significantly increased at T2 as compared with T1 (p < 0.001), and was maintained at the same high level at T3 (T1 versus T3: p < 0.001). Within the control group the differences between the different measures were not significant (p > 0.06).

Effects of Group at T1, T2 and T3 on (a) knowledge about spread, (b) attitude towards condom use and (c) male learners' attitude towards friends with HIV/AIDS.

Knowledge about causes of sexually transmitted infections. Only a significant effect of Time was found indicating that knowledge about the causes of sexually transmitted infections increased over time, but this could not be attributed to an effect from Laduma.

Attitude towards condom use. Analysing the interaction effect of Group and Time on attitude towards condom use (Table 2), we found no difference between the intervention and control group at baseline. An effect of Group was found in the predicted direction at both T2 (p < 0.001) and at T3 (p < 0.001). At both post-tests, participants in the intervention group had a more positive attitude towards condom use than participants in the control group (see Figure 2b). Analyses of the differences between mean scores within the intervention group showed that the positive attitude towards condom use significantly increased after reading Laduma (T2) compared with the baseline level (p < 0.001), and this was maintained at the same level at T3 (T1 versus T3: p < 0.001; T2 versus T3: p = 0.96). Within the control group there was no significant difference between the three time measures (p >0.30).

Attitude towards persons infected with sexually transmitted infections or HIV/AIDS. The significant three-way interaction effect of Gender, Group and Time revealed that the two-way interaction effect of Group and Time was significant among males (p <0.05) (see Figure 2c), but not among females. Analyses of the differences between mean scores among males within the intervention group showed that the attitude towards persons with a sexually transmitted infection or HIV/AIDS was more positive at T3 than at baseline (p < 0.05). The differences between the mean scores among males within the control group were not significant (p > 0.10).

Impact of Laduma on sexual behaviour, condom use and future intentions

Sexual behaviour and condom use. Of all learners (n = 1168) 43.3% reported having had sex in the last six months before the study, with the percentage of male learners that was sexually active being higher (53.6%; n = 281) than the percentage of female learners (34.2%; n = 202), χ2 (1, n = 1115) = 42.48, p < 0.001. A hierarchical logistic regression analysis was performed with having or not having had sex in the six-week period between T2 and T3 as the dependent variable. Covariates in the model at step 1 were ‘having had sex in the last six months’ before the intervention (past sexual behaviour), language, Gender and Group (intervention versus control); at step 2 the interaction of Gender and Group was added to the model. Sexual activity at the last measurement was strongly predicted by sexual activity in the six months prior to the study, Wald (1) = 82.33, p < 0.001, and to a lesser extent by Gender, Wald (1) = 20.72, p < 0.001, with the percentage of males being sexually active in the six weeks between T2 and T3 being higher (42.5%) than the percentage of females (21.9%). Language did not contribute to the prediction of sexual activity, Wald (1) = 2.57, p = 0.11.

Of all learners who at baseline reported to have had sex in the six months preceding the study (n = 484), 42.4% reported having used a condom every time they had sex. A hierarchical logistic regression analysis was performed with condom use at T2 as the dependent variable. Covariates at step 1 were condom use at baseline, language, Group and Gender. The interaction effect between Gender and Group was included at step 2. All learners that had sex in the period between six months before the study and six weeks after the intervention were included in this analysis. Consistent condom use at six weeks after the intervention was predicted by past condom use (6 months preceding the study), Wald (1) = 47.02, p < 0.001. All other covariates had no significant predictive value (p > 0.25).

Of all learners who had sex during the six months before the study and did not consistently use condoms, 75.2% (n = 103) also did not consistently use condoms during the six-week period after the intervention. Of the learners who had sex six months prior to the study and reported using condoms consistently during that period, 71.6% (n = 73) also reported using condoms consistently in the six-week period after the intervention. The intervention (reading Laduma once) had thus no significant effect on consistent condom use six weeks later.

Intentions to use or not use condoms or to abstain. At T3 learners were asked for their intended choice with respect to preventive behaviour for the next year. Of all learners in the control group (n = 346), 41.9% intended not to have sex, 52.3% intended to have sex with a condom and a small minority of 5.8% intended to have sex without a condom. For the learners in the intervention group (n = 292) these percentages were significantly different, χ2 (2, n = 516) = 8.19, p < 0.05, with 28.1% intending not to have sex, 65.1% intending to have sex with a condom and 6.8% not intending to use a condom. More learners in the intervention group than in the control thus seem to intend to have sex with a condom.

A hierarchical logistic regression analysis was performed on all learners who intended to have safe sex with a condom (n = 371) or to abstain from sex for the next year (n = 227), with the intention to analyse which variables explained the kind of preventive behaviour of their choice (abstinence or condom use). Covariates at step 1 were language, Gender, Group and past sexual behaviour, at step 2 the interaction of Gender and Group was added to the model. The variables that significantly contributed to the prediction of the kind of safe sex choice were Gender, Wald (1) = 59.50, p < 0.001, Group, Wald (1) = 21.70, p < 0.001 and past sexual behaviour, Wald (1) = 21.13, p < 0.001. Of the learners in the intervention group 69.9% intended to have sex with a condom as compared with 55.5% in the control group, while 30.9% intended to abstain from having sex as compared with 44.5% in the control group. Male learners reported a higher intention (79.54%) to have sex with a condom than female learners (47.0%). Just over half of the female learners (53.0%) intended to abstain from sex in the next year against 20.5 of the male learners. Learners who had sex in the past had a much higher intention (78.9%) to have sex with a condom for the next year than learners who did not have sex yet (52.3%).

DISCUSSION

This study reports a significant increase in knowledge about the spread of sexually transmitted infections in male and female learners after a single reading of a systematically developed educational photo-novella. In addition, reading Laduma contributed to a more positive attitude to condom use in male and female learners six weeks after the intervention. The study also showed that male learners reading Laduma reported a more positive attitude towards persons infected with a sexually transmitted infection or HIV/AIDS, lasting at least 6 weeks. These positive attitudes are important in influencing intentions to use condoms as well as in creating a social environment that is supportive of people living with HIV/AIDS, a condition perceived as threatening and stigmatizing.

Although in Laduma a lot of attention is paid to enhance an open discussion about sexually transmitted infections, the intervention had no significant effect on communication with boy- or girlfriends, with other friends or with parents about sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS and about prevention of infection. No change was found on having sex and on condom use during the six weeks after the intervention. However, an effect was found on future intention to use condoms in the next year. Learners who read Laduma reported a higher intention to use condoms when having sex in the next year than learners in the control group. However, while Laduma was successful in influencing the learners' intentions to use condoms, it did not influence their current sexual practice and condom use behaviour.

Our findings confirm that awareness of the problem, positive attitudes towards the desired behaviour and a positive intention to perform the desired behaviour are prerequisites but not sufficient to realize actual behaviour change (Prewitt, 1989; Petosa and Wessinger, 1990).

To achieve the adoption of desired behaviours learners also need to have the confidence and skills to be able to execute the preventive behaviour. Consistent condom use, for example, is a complex behaviour requiring a series of actions. These actions include talking about sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS with ones' partner, talking about and negotiating condom use, buying condoms or requesting it from clinic staff, putting on and removing the condom in a way to enhance enjoyment and minimize embarrassment. To increase self-confidence (self-efficacy) and self-regulatory skills to perform a specific preventive behaviour among specific social groups as school learners, strategies like enactive mastery learning, coping modelling, mastery modelling, instructive modelling and guided skill perfection may be more ap propriate (Bandura, 1997). Recent reviews of the literature on the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS education programmes for school youth and adolescents in developing countries and in Southern Africa confirm that programmes, which showed success in terms of adoption of safer sexual behaviours frequently include a strong skills development component (Van Empelen et al., unpublished manuscript, 2001). Effective programmes also seem to have appropriately trained educators who have time available and the necessary skills to implement the programmes (Kirby, 1997).

Our data strongly confirm the need to develop programmes that teach self-regulatory skills. Any attempt to address the issue of sexually transmitted infections within school curricula requires further a sound understanding of human sexuality, gender issues and role definitions as it pertains to relationships and the specific context of the learner. In taking up the call to address the issue of sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS through the formal school curricula, it is imperative that the needs of the individual learner are taken into account. This calls for tailored programmes that address the concerns of both sexually active and inactive learners. Self-regulatory skills development needs to target both groups and, for example, teach assertiveness related to abstinence (no I am not ready for sex) and condom use (no I will not have sex without a condom).

The evaluation of Laduma also suggests that planned sexual programmes that promote condom use do not necessarily lead to an increase in sexual activity. Interventions like Laduma ought to be made available to young people in order to help start out there lives based on informed decisions and to create an environment that is normative to healthy sexual practices.

This research was made possible by a research grant from NACOSA. The authors would like to thank Nilen Kambaran for his help in preparing the data set, and the Department of Education–KwaZulu-Natal for their approval to conduct the study.

REFERENCES

Colvin, M. (

Kok, G., Schaalma, H., De Vries, H., Parcel, G. and Paulussen, T. (

Prewitt, V. R. (

Roter, D. L., Rudd, R. E., Frantz, S. C. and Comings, J. P. (

Author notes

1Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa, 2Maastricht University, The Netherlands and 3University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa