-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

J.H.E. Promislow, D.D. Baird, A.J. Wilcox, C.R. Weinberg, Bleeding following pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation, Human Reproduction, Volume 22, Issue 3, March 2007, Pages 853–857, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del417

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation is common, but little has been reported about the associated bleeding. We compared women’s bleeding following a pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation with their typical menstruation. METHODS: Women provided daily urine samples while trying to become pregnant and recorded the number of pads and tampons used each day. Thirty-six women had complete bleed data for a loss before 6 weeks’ gestation and one or more non-pregnant cycles. RESULTS: Mean bleed length following a pregnancy loss was 0.4 days longer than the woman’s average menstrual bleed (P = 0.01), primarily because of more days of light bleeding. Although there was no overall increase in the total number of pads plus tampons used, women with losses bled less than their typical menses following pregnancies of very short duration and more than usual for the pregnancies lasting the longest. CONCLUSIONS: Overall, the bleeding associated with pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation is similar to menstrual bleeding and unlikely to be recognized as pregnancy loss. The intriguing finding that pregnancies of very short duration were associated with less bleeding than the woman’s typical menses might reflect endometrial factors associated with loss.

Introduction

Studies of women seeking medical care for miscarriage have reported that the bleeding that accompanies miscarriage is heavier and more prolonged than typical menses (Haines et al., 1994; Nielsen and Hahlin, 1995; Chung et al., 1998; Nielsen et al., 1999; Bagratee et al., 2004). However, most of these clinically reported miscarriages occurred after 6 weeks’ gestation; the bleeding that accompanies earlier pregnancy loss has not been carefully described. Such early losses are common: approximately a quarter of all pregnancies end before 6 weeks’ gestation, often before the pregnancy has received any medical attention or even become apparent to the woman (Wilcox et al., 1990; Zinaman et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2003). Using data from a prospective study of women who were attempting pregnancy, we describe in detail the bleeding that accompanies pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation, and we compare those patterns of bleeding with the women’s ordinary menstrual bleeding.

Materials and methods

Study participants were members of the North Carolina Early Pregnancy Study, a prospective cohort study conducted from 1982 to 1985 involving 221 women who were attempting pregnancy (Wilcox et al., 1988). These women had no known fertility problems or major chronic disease. Participation began when women discontinued contraception and continued until 8 weeks past their last menstrual period if they became pregnant or for 6 months if they did not. During this time, participants collected daily first-morning urine specimens and kept daily diary records of their menstrual bleeding (number of pads and tampons). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and participating women provided informed consent.

Ovulation was identified using measurements of estrogen and progesterone metabolites in urine (Baird et al., 1991). Pregnancy was detected using a highly sensitive and specific polyclonal radioimmunoassay for urinary HCG (Armstrong et al., 1984). This assay measured intact HCG and β-HCG with <1% cross-reaction with human LH (McChesney et al., 2005). The lowest HCG concentration detectable by the immunoradiometric assay was 0.01 ng/ml. Three consecutive days of urinary HCG >0.025 ng/ml was the criterion for pregnancy. This criterion ensured high specificity and was determined from a parallel study of urinary HCG levels in women who had undergone a tubal ligation. Pregnancy loss was detected by a subsequent fall in urinary HCG. We restricted our study to pregnancies that ended <6 weeks after the last menstrual period, with the day of loss considered to be the first day of vaginal bleeding associated with the fall in HCG (Wilcox et al., 1988). Over-the-counter pregnancy test kits were not available at the time of the study, and only one woman who lost a pregnancy before 6 weeks’ gestation reported that the pregnancy was clinically detected.

Following World Health Organization guidelines (World Health Organization Task Force on Adolescent Reproductive Health, 1986), we defined the length of a bleed period as the number of days from the start of bleeding up to and including the day before a bleed-free interval of at least 2 days. Menstrual discharge consists of tissue fluid (20–40% of the total discharge) and fragments of the endometrium in addition to blood (50–80% of the total discharge); we refer to this discharge simply as bleeding, as is customary (Oats and Abraham, 2005).

We used the number of pads and tampons per day as a measure of bleeding quantity, focusing on comparisons within women. Women can differ from one another in their use of pads and tampons for reasons related more to personal habits than to volume of menstrual discharge. Because this variability between women is controlled in a within-woman analysis, it is more informative to conduct within-woman analyses of bleeding (comparing an early loss with the same woman’s regular menses) than to make comparisons across women. In support of this, studies comparing pad and tampon counts with quantitative measurement of blood loss across women have reported considerably higher correlation coefficients when the studies included multiple cycles per woman [0.61 (Higham and Shaw, 1999) and 0.74 (Higham et al., 1990)] than when they did not [0.14 (Fraser et al., 1981) and 0.30 (Warner et al., 2004)].

Women may also differ in their patterns of use of pads versus tampons. However, women in this study were fairly consistent from one period to the next in their use of pads versus tampons. The mean percentage of tampons used per period [100 × tampons/(pads + tampons)] was 62%, and the mean within-woman SD in the percentage of tampons used per period was 9%.

Forty-four women had 48 pregnancy losses before 6 weeks’ gestation during their study participation. One of these women had a single loss for which she reported no associated bleeding; because her reporting was incomplete in other respects, we believed her report of no bleeding could have been a recording error, and we have excluded her from this analysis. Of the remaining women, 36 provided complete data on bleed length and pad–tampon use for at least one regular menses in addition to a pregnancy loss bleeding episode. One non-conception cycle was excluded because no bleeding was reported. All but one of the 36 women were white; most were college-educated (72%). The median age was 29 years (range 24–36 years), and 61% were parous at enrolment.

These 36 women in the analysis sample had 38 pregnancy losses before 6 weeks’ gestation (two women had two losses). Information on bleeding after an ovulatory non-conception cycle was available for 1–7 menses per woman (median = 3) for 198 non-conception menses. Analyses were based on differences between the within-woman averages. For each woman, a value for each bleed characteristic was calculated for both the non-conception and the pregnancy loss bleeds. If a woman had more than one non-conception or pregnancy loss bleed, then the mean value of the bleed characteristic was used. A bleed characteristic difference was then computed by subtracting the non-conception bleed value from the pregnancy loss bleed value, and differences were tested with a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Non-parametric correlation statistics and tests for difference were used because of the inherent non-normality of some of the bleed characteristic variables. The 25th and 75th percentile values for the distributions are presented, but means and SEs are also presented for ease of comparison with other published bleed length values. All P-values cited are two-sided, with a significance level of ≤ 0.05.

The pregnancy losses represented a range of durations and amounts of HCG production, which we hypothesized might also be related to the pattern of bleeding. To explore this, we used two markers: maximum level of HCG obtained during the pregnancy and the length of the failed pregnancy (days from ovulation to onset of bleeding).

Results

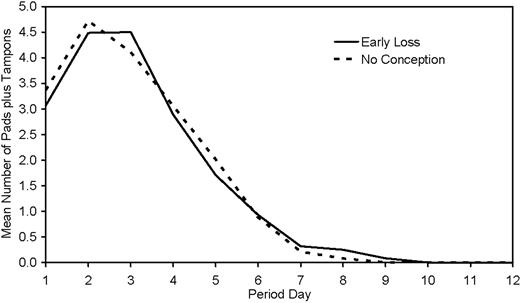

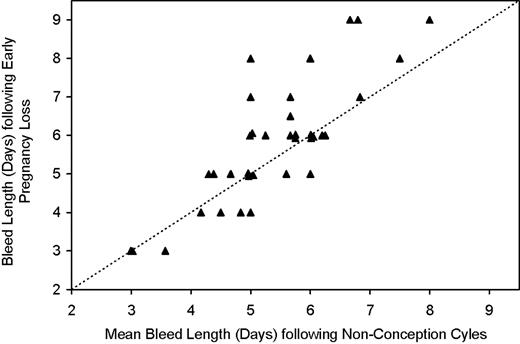

The overall pattern of bleeding after a pregnancy loss of <6 weeks’ gestation was remarkably similar to the pattern seen with regular menses (Figure 1). There was a high correlation between the length of a woman’s bleeding with pregnancy loss and her usual bleeding with menses (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.78; P < 0.001) (Figure 2). However, a closer look at within-women comparisons revealed some differences. Bleeding after a pregnancy loss tended to be slightly longer, by 0.4 days (P = 0.01) (Figure 2, Table I). This increased duration of bleeding was primarily because of an increase in light bleeding, defined as days with up to three pads and tampons. The mean increase in duration of light bleeding was 0.5 days (P = 0.004). Consistent with the additional light bleeding with pregnancy loss, the mean daily number of pads and tampons was slightly decreased, although not significantly, in the pregnancy loss bleeding (Table I). Pregnancy loss bleeding showed no increase in either the total number of pads and tampons or the maximum number of pads and tampons in 1 day (Table I).

Mean daily pad plus tampon use total by day of bleed period for 36 women for bleeds following their early pregnancy losses (solid line) versus their cycles with no detected conception (dashed line). Mean daily pad plus tampon totals are the across-women means of each woman’s mean values. Every menses contributes data for all 12 days (zero values after bleeding ends).

Plot of each woman’s bleed length (days) for the bleed period following her early pregnancy loss (mean value used for the two women with two losses each) versus her mean bleed length (days) for her bleed periods following cycles with no detected conception (n = 36 women). Dashed line is line of equality.

Within-woman comparison of bleed characteristics associated with a pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation versus menstrual bleed characteristics following cycles with no detected conception (n = 36 women)

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use . | Early loss . | No conception . | Early loss − no conception . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean . | SE . | 25tha . | 75tha . | Mean . | SE . | 25th . | 75th . | Mean . | SE . | P-valueb . |

| Length of use (days) | 5.8 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 18.2 | 1.2 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 18.4 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 24.3 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.94 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 5.2 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.53 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 3.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 4.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Period day of heaviest use | 2.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.78 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.004 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.90 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use . | Early loss . | No conception . | Early loss − no conception . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean . | SE . | 25tha . | 75tha . | Mean . | SE . | 25th . | 75th . | Mean . | SE . | P-valueb . |

| Length of use (days) | 5.8 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 18.2 | 1.2 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 18.4 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 24.3 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.94 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 5.2 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.53 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 3.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 4.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Period day of heaviest use | 2.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.78 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.004 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.90 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

25th and 75th percentile values.

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Numbers in parentheses indicate daily total for pad + tampon use.

One bleed episode has a single day with pads + tampons = 0.

Within-woman comparison of bleed characteristics associated with a pregnancy loss before 6 weeks’ gestation versus menstrual bleed characteristics following cycles with no detected conception (n = 36 women)

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use . | Early loss . | No conception . | Early loss − no conception . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean . | SE . | 25tha . | 75tha . | Mean . | SE . | 25th . | 75th . | Mean . | SE . | P-valueb . |

| Length of use (days) | 5.8 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 18.2 | 1.2 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 18.4 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 24.3 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.94 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 5.2 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.53 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 3.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 4.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Period day of heaviest use | 2.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.78 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.004 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.90 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use . | Early loss . | No conception . | Early loss − no conception . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Mean . | SE . | 25tha . | 75tha . | Mean . | SE . | 25th . | 75th . | Mean . | SE . | P-valueb . |

| Length of use (days) | 5.8 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 18.2 | 1.2 | 12.5 | 23.0 | 18.4 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 24.3 | −0.2 | 0.9 | 0.94 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 5.2 | 0.4 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 7.3 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.53 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 3.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 4.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Period day of heaviest use | 2.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.78 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | 3.8 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.004 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.90 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

25th and 75th percentile values.

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Numbers in parentheses indicate daily total for pad + tampon use.

One bleed episode has a single day with pads + tampons = 0.

Pregnancies ending in losses before 6 weeks’ gestation are not all the same, either in their duration or in the amount of HCG they produce. Among the 38 pregnancy losses in this analysis, the time from conception (i.e. ovulation) to onset of bleeding ranged from 11 to 28 days. Similarly, maximal HCG concentration varied more than a hundred-fold, from 0.035 to 46 ng/ml. We explored whether the bleeding patterns after a loss varied according to the pregnancy duration and the level of HCG measured (Table II).

Correlation of bleed characteristics with markers of the strength of the lost pregnancy (n = 36 women)

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use (within-woman difference)a . | Pregnancy marker . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Maximum HCG . | Days from ovulation to bleeding . | ||

| . | ρb . | P-value . | ρb . | P-value . |

| Length of use (days) | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.003 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.004 |

| Period day of heaviest use | −0.11 | 0.53 | −0.29 | 0.09 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | −0.38 | 0.02 | −0.42 | 0.01 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.02 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use (within-woman difference)a . | Pregnancy marker . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Maximum HCG . | Days from ovulation to bleeding . | ||

| . | ρb . | P-value . | ρb . | P-value . |

| Length of use (days) | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.003 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.004 |

| Period day of heaviest use | −0.11 | 0.53 | −0.29 | 0.09 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | −0.38 | 0.02 | −0.42 | 0.01 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.02 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

Value for woman’s bleed following her early loss minus mean value for her bleeds following cycles with no detected conception.

Spearman correlation coefficient.

Numbers in parentheses indicate daily total for pad + tampon use.

One bleed episode has a single day with pads + tampons = 0.

Correlation of bleed characteristics with markers of the strength of the lost pregnancy (n = 36 women)

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use (within-woman difference)a . | Pregnancy marker . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Maximum HCG . | Days from ovulation to bleeding . | ||

| . | ρb . | P-value . | ρb . | P-value . |

| Length of use (days) | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.003 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.004 |

| Period day of heaviest use | −0.11 | 0.53 | −0.29 | 0.09 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | −0.38 | 0.02 | −0.42 | 0.01 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.02 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

| Characteristics of pad + tampon use (within-woman difference)a . | Pregnancy marker . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Maximum HCG . | Days from ovulation to bleeding . | ||

| . | ρb . | P-value . | ρb . | P-value . |

| Length of use (days) | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.66 |

| Total number used during bleed period | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.003 |

| Maximum number used in 1 day | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Mean number per bleeding day | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.004 |

| Period day of heaviest use | −0.11 | 0.53 | −0.29 | 0.09 |

| Number of light days (0–3)c,d | −0.38 | 0.02 | −0.42 | 0.01 |

| Number of medium days (4–6) | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.02 |

| Number of heavy days (7+) | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.66 |

Value for woman’s bleed following her early loss minus mean value for her bleeds following cycles with no detected conception.

Spearman correlation coefficient.

Numbers in parentheses indicate daily total for pad + tampon use.

One bleed episode has a single day with pads + tampons = 0.

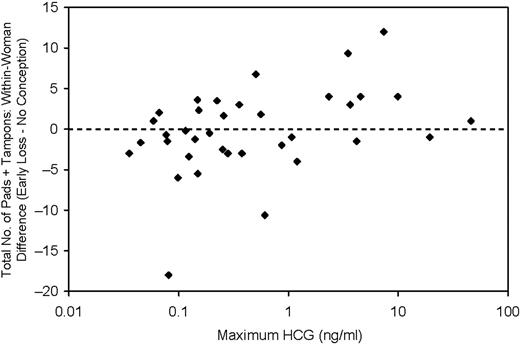

We found no relation between maximal HCG concentration or pregnancy duration and the number of days of bleeding. However, the total number of pads and tampons used in association with the pregnancy loss did correlate with both maximum HCG (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.37; P = 0.02) and days from ovulation to bleeding (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.48; P = 0.003). As one might expect, women with higher maximal HCG levels and longer pregnancy duration used more pads and tampons for the bleeding associated with their pregnancy loss than they did for their typical menses. However, we unexpectedly also found that women whose pregnancies had lowest maximum HCG values and were of shortest duration tended to use fewer pads and tampons than they did for ordinary menses (Figure 3). This difference was most notable between women in the lowest and highest quartiles of maximum HCG (Table III).

Plot of the within-woman difference in total number of pads plus tampons used during bleed period (total number used for bleed following early pregnancy loss minus mean of totals for bleeds following cycles with no detected conception) versus the maximum HCG value (shown on a log scale) obtained for the pregnancy that was lost (n = 36 women). Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.37 (P = 0.02).

Within-woman difference in total number of pads plus tampons used per bleed by quartile of maximum HCGa

| Maximum HCG (ng/ml) . | Women (n) . | Total number of pads + tampons: within-woman difference (early loss − no conception) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SE . |

| ≤0.12 | 9 | −3.12 | 2.01 |

| 0.12–0.27 | 9 | −0.23 | 1.07 |

| 0.27–1.65 | 9 | −1.34 | 1.64 |

| >1.65 | 9 | 3.87 | 1.48 |

| Maximum HCG (ng/ml) . | Women (n) . | Total number of pads + tampons: within-woman difference (early loss − no conception) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SE . |

| ≤0.12 | 9 | −3.12 | 2.01 |

| 0.12–0.27 | 9 | −0.23 | 1.07 |

| 0.27–1.65 | 9 | −1.34 | 1.64 |

| >1.65 | 9 | 3.87 | 1.48 |

Overall P-value based on rank correlation = 0.01.

Within-woman difference in total number of pads plus tampons used per bleed by quartile of maximum HCGa

| Maximum HCG (ng/ml) . | Women (n) . | Total number of pads + tampons: within-woman difference (early loss − no conception) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SE . |

| ≤0.12 | 9 | −3.12 | 2.01 |

| 0.12–0.27 | 9 | −0.23 | 1.07 |

| 0.27–1.65 | 9 | −1.34 | 1.64 |

| >1.65 | 9 | 3.87 | 1.48 |

| Maximum HCG (ng/ml) . | Women (n) . | Total number of pads + tampons: within-woman difference (early loss − no conception) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SE . |

| ≤0.12 | 9 | −3.12 | 2.01 |

| 0.12–0.27 | 9 | −0.23 | 1.07 |

| 0.27–1.65 | 9 | −1.34 | 1.64 |

| >1.65 | 9 | 3.87 | 1.48 |

Overall P-value based on rank correlation = 0.01.

Discussion

In the North Carolina Early Pregnancy Study, the bleeding accompanying a woman’s pregnancy loss after <6 weeks’ gestation was, on the whole, not remarkably different from her typical menses. Overall, we saw no evidence of heavier bleeding after the pregnancy loss, either on a given day or over the entire bleeding episode. There was a slight tendency for women to bleed longer following pregnancy loss than they did for their typical menses, but this difference was small (0.4 days) and entirely because of light bleeding. The evidence suggests that most women would be unlikely to distinguish the bleeding episode that follows an early pregnancy loss from their ordinary menses.

Our results are consistent with those from a study of highland Bolivian women. In this study of 189 women, gestational age of the pregnancy losses was not reported, but for the 14 losses that were likely to have happened at very early gestational ages, the mean bleed duration of 3.3 days did not differ markedly from the study population’s mean non-conception menses duration of 3.6 days (Vitzthum et al., 2001).

Most information on bleeding with pregnancy loss comes from studies of expectant management of women seeking medical care for miscarriage. Most of these miscarriages occurred in the latter half of the first trimester. Mean length of bleeding with these miscarriages was in the range of 9–11 days (Haines et al., 1994; Nielsen and Hahlin, 1995; Chung et al., 1998; Nielsen et al., 1999; Bagratee et al., 2004). For comparison, the mean duration of menstrual bleeding among a large cohort of predominantly white, college-educated, US women has been reported to be 5.3 days (Cooper et al., 1996), virtually the same as the 5.4 days seen for non-conception cycles in our study (Table I).

Although variations in maximal HCG production and pregnancy duration were unrelated to the length of the bleeding associated with the loss in Early Pregnancy Study women, they were correlated with intensity of bleeding (compared with usual menses). An increase in bleeding for longer lasting pregnancies is not surprising; such pregnancies will generally have reached a later stage of development, with more advanced decidualization and trophoblast invasion (Cunningham et al., 2005). However, the reduction in bleeding seen with pregnancy losses of shorter duration and lower HCG production was surprising. It may be that a menstrual cycle with poorer endometrial development may increase the risk of very early pregnancy loss. A related hypothesis is that a hormonally suboptimal cycle predisposes the woman to both suboptimal endometrial development and very early pregnancy loss, producing an association of the two. Alternatively, impending early loss may produce a change in the endometrium that results in reduced shedding of tissue.

In conclusion, we found that the bleeding after a pregnancy loss of <6 weeks’ gestation was only slightly longer than the woman’s typical menstrual bleeding. This is counter to expectations based on observations of later miscarriages. Overall, there was no meaningful difference in the number of pads and tampons women used after a pregnancy loss compared with what they used in a typical menstrual period (either as recorded per day or in total over the course of the bleeding episode). In general, it seems unlikely that bleeding after an early pregnancy loss is different enough from a woman’s usual menstrual bleeding to trigger suspicion of pregnancy loss.

Maximal HCG production and pregnancy duration were, however, correlated with the amount of bleeding associated with the loss. Unexpectedly, women bled less than usual following those pregnancy losses with the shortest duration and lowest maximal HCG production. This apparent reduction in bleeding after the very earliest losses bears further investigation, because it could indicate the presence of possible physiologic changes in the earliest days after conception and implantation that may be relevant to fecundity and the risk of early loss.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr B.Gladen and Dr A.M.Jukic for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr D.R.Bob McConnaughey for preparing the data set. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and NIEHS.