-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Xiaodong Qi, Yang Li, Shinji Honda, Steve Hoffmann, Manja Marz, Axel Mosig, Joshua D. Podlevsky, Peter F. Stadler, Eric U. Selker, Julian J.-L. Chen, The common ancestral core of vertebrate and fungal telomerase RNAs, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 41, Issue 1, 1 January 2013, Pages 450–462, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks980

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein with an intrinsic telomerase RNA (TER) component. Within yeasts, TER is remarkably large and presents little similarity in secondary structure to vertebrate or ciliate TERs. To better understand the evolution of fungal telomerase, we identified 74 TERs from Pezizomycotina and Taphrinomycotina subphyla, sister clades to budding yeasts. We initially identified TER from Neurospora crassa using a novel deep-sequencing–based approach, and homologous TER sequences from available fungal genome databases by computational searches. Remarkably, TERs from these non-yeast fungi have many attributes in common with vertebrate TERs. Comparative phylogenetic analysis of highly conserved regions within Pezizomycotina TERs revealed two core domains nearly identical in secondary structure to the pseudoknot and CR4/5 within vertebrate TERs. We then analyzed N. crassa and Schizosaccharomyces pombe telomerase reconstituted in vitro, and showed that the two RNA core domains in both systems can reconstitute activity in trans as two separate RNA fragments. Furthermore, the primer-extension pulse-chase analysis affirmed that the reconstituted N. crassa telomerase synthesizes TTAGGG repeats with high processivity, a common attribute of vertebrate telomerase. Overall, this study reveals the common ancestral cores of vertebrate and fungal TERs, and provides insights into the molecular evolution of fungal TER structure and function.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic chromosomes are terminally capped by special DNA–protein complexes, called telomeres. Telomeric DNA typically shortens with each cell division owing to incomplete end replication, ultimately resulting in chromosome instability and cellular senescence (1). Counteracting telomere shortening, telomerase synthesizes short telomeric DNA repeats onto chromosome termini. Human telomerase is highly processive, capable of synthesizing hundreds of telomeric DNA repeats onto a given primer. Mutations that impair telomerase function result in stem cell defects and have been linked to a growing number of human diseases, including dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (2). Recently, mutations decreasing telomerase repeat addition processivity have been linked to familial pulmonary fibrosis (3,4).

Telomerase functions as a ribonucleoprotein enzyme, requiring the catalytic telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and the intrinsic telomerase RNA (TER) component for enzymatic activity. The TER contains a short template that specifies the telomeric repeat sequence synthesized and conserved structural domains that serve as binding sites for telomerase accessory proteins. The TERT protein is highly conserved, containing four structural domains: TEN, TRBD, RT and CTD. In comparison, TER is divergent in size and sequence, even among closely related clades. Over the past two decades, structural studies of TER from ciliates, vertebrates and yeasts revealed two ubiquitous structural domains: the template–proximal pseudoknot and a template–distal stem-loop moiety [termed CR4/5 in vertebrates, three-way junction (TWJ) in budding yeasts and stem-loop IV in ciliates] (5–8). The template–adjacent pseudoknot structure forms a unique triple helix and is essential for telomerase function (9–12). In the template-distal moiety, the vertebrate CR4/5 domain contains a highly conserved 4-bp P6.1 stem with an essential 5-nucleotide (nt) L6.1 loop that is not found in either the budding yeast TWJ or the ciliate stem-loop IV (13,14). In ciliates and vertebrates, these two structural domains bind independently to TERT and are both essential for telomerase activity, an attribute not yet demonstrated within yeasts (15,16).

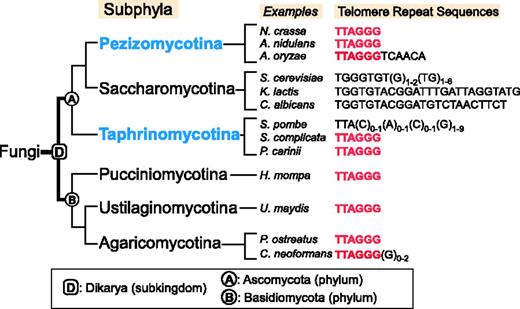

Fungal telomerase has been extensively studied in budding yeasts (Saccharomycotina), such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis, and recently in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Taphrinomycotina), both belonging to the Ascomycota phylum. However, little is known of telomerase from Pezizomycotina (commonly known as filamentous ascomycetes), which includes genetically tractable model organisms Neurospora crassa and Aspergillus nidulans (Figure 1). Pezizomycotina is the largest subphylum within Ascomycota, representing 90% of known ascomycete species, while Taphrinomycotina is an early-branching subphylum, which includes S. pombe (17). Many species from Pezizomycotina and the distantly related Basidiomycota phyla have the vertebrate-type TTAGGG telomeric repeat (18–23). While budding and fission yeasts are useful model systems for the study of telomere biology, their telomere repeats are longer than those of filamentous ascomycetes and often irregular (Figure 1). Moreover, telomerase from most yeasts are non-processive, whereas telomerase from most vertebrates are highly processive—capable of adding multiple repeats to a given primer before complete enzyme–product dissociation. The processivity of non-yeast fungal telomerase was not known before this study.

Evolutionary relationships and telomere repeat sequence of major fungal subphyla. The evolutionary relationships of the Ascomycota subphyla (Pezizomycotina, Saccharomycotina and Taphrinomycotina) and the Basidiomycota subphyla (Pucciniomycotina, Ustilaginomycotina and Agaricomycotina) are depicted based on recent phylogenomic studies of fungal species (17,24,25). Branch lengths are not proportional to evolutionary time. The names of subkingdom Dikarya (D), subphylum Ascomycota (A) and subphylum Basidiomycota (B) are indicated at nodes in the tree. Telomere repeat sequences of representative species from each subphylum are shown. The vertebrate-type sequence TTAGGG is shown in red. The subphyla Pezizomycotina and Taphrinomycotina studied in this work are highlighted in blue.

We herein report the identification of novel TER sequences from 74 fungal species, 73 filamentous ascomycetes from Pezizomycotina and Saitoella complicata from Taphrinomycotina. Phylogenetic comparative analysis combined with functional studies of these newly identified fungal TERs revealed structural features and biochemical attributes akin to vertebrate TER and not budding yeast TER. Moreover, the structural and functional conservation between the distantly related vertebrate and non-yeast fungal TERs indicates that these structural elements and functional attributes are descended from a common ancestral TER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ascomycete strains

Wild-type N. crassa (strain FGSC 2489) and A. nidulans (strain FGSC A4) were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC). Vegetative growth, transformation and mating of N. crassa were carried out following standard procedures (26). A. nidulans was grown as previously described (19). Mycosphaerella graminicola (strain IPO323) was obtained from Dr Gert Kema and grown in yeast glucose broth (1% yeast extract and 3% glucose) at 18°C. S. complicata (strain Y-17804) was obtained from the NRRL Collection and grown in YM broth (0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% malt extract, 0.5% peptone and 1% glucose) at room temperature. Recombinant N. crassa strains used and generated in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Cloning of telomeric DNA

Telomeric DNA was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified and cloned as previously described, with minor modifications (27). Genomic DNA was isolated from 100 mg of homogenized N. crassa mycelia tissue using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In a 20-µl reaction, 200 ng of N. crassa genomic DNA was incubated with 6 units of terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT, USB) in TdT buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM KOAc, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM deoxycytidine triphosphat (dCTP)] at 37°C for 30 min. After heat inactivation at 70°C for 10 min, the poly(C)-extended genomic DNA was PCR amplified in 1× PCR buffer [67 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 5% glycerol, 0.01% Tween-20], 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), 0.4 µM of oligo-dG primer 5′-CGGGATCCG18-3′ and a primer specific to the subtelomeric region of chromosome IIIF or VR. Nested PCR was performed using 1 µl of 1/100× of the aforementioned PCR mixture in 1× HF buffer (Finnzymes), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 unit of Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), 0.4 µM of oligo-dG primer and a nested subtelomeric primer. The PCR products were gel purified, cloned into the pZero vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

Cloning of N. crassa TERT (NcrTERT)

A hypothetical tert gene (GenBank accession no. XM958854) was found in the N. crassa genome database (Broad Institute) by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and characterized by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) using the FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequence of the cloned Ncr-tert cDNA was deposited in GenBank (Accession no. JF794773).

Generation of N. crassa recombinant strains

The recombinant NcrTERT-3xFLAG N. crassa strain was generated by gene replacement. A 3.2-kb recombinant DNA cassette was introduced into the Ku80-deficient (Δmus-52) N. crassa strain by electroporation to replace the endogenous NcrTERT gene through homologous recombination (Supplementary Table S1). The Ku80-deficient strain permits efficient homologous recombination by eliminating non-homologous end joining (28). The DNA cassette contained 1 kb of the 3′ portion of the Ncr-tert genomic sequence, a 3xFLAG tag fused in-frame, the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hph) drug-resistant gene and 500 bp of the 3′ intergenic sequence (Supplementary Figure S1A). The Ncr-tert coding sequence and the 3′ intergenic sequence were PCR amplified from genomic DNA, and the 3xFLAG-loxP-hph-loxP was PCR amplified from the plasmid p3xFLAG::hph::loxP (29), before overlapping PCR. Hygromycin-resistant transformants were selected (29) and screened for the recombinant NcrTERT-3xFLAG gene by Southern blot analysis as previously described (26). Transformants lacking the endogenous TERT gene were crossed with the wild-type strain, generating a homokaryotic NcrTERT-3xFLAG::hph+ strain expressing the FLAG-tagged NcrTERT protein (Supplementary Table S1).

NcrTER template mutants were generated by site-directed PCR mutagenesis and cloned into the pCCG::C-Gly::3xFLAG vector (29) with BamHI and EcoRI sites. Mutant NcrTER plasmids were linearized by StuI digestion, introduced into N. crassa strain NC1 by electroporation and integrated into a non-functional his− locus. Selection of his+ transformants was performed in Vogel’s minimum medium with 2% sorbose in place of sucrose.

Purification of N. crassa telomerase

Nuclei were isolated from 2 g of N. crassa mycelium homogenized in a bead beater using five 10-s pulses at 10-s intervals in ice-cold solution of 1 M sorbitol, 7% Ficoll (w/v), 20% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2 and 1% Triton X-100. The cell slurry was centrifuged at 1500g for 10 min, and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 15 000g for 20 min. The nuclear pellet was washed once with wash buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol and 0.6 M sucrose], resuspended and lysed in CHAPS lysis buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 400 mM NaCl, 0.5% CHAPS, 5% glycerol, 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM MgCl2, supplemented with 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)]. The nuclear extract was cleared by centrifugation at 14 000g for 10 min. Two milliliters of nuclear extract was immediately applied to an XK26/60 Sephacryl S-500 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with column buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 400 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol]. Five-milliliter fractions were collected, and telomerase activity of each fraction was measured by telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay. The peak fractions were pooled and applied to 20 µl of anti-FLAG M2 antibody agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) pre-washed three times with 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl]. The sample was incubated at 4°C for 1 h with gentle rotation, centrifugated at 1000g for 15 s, and washed with 300 µl of 1× TBS buffer three times. RNA was extracted from the beads using 100 µl of RNA extraction buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)], followed by acid phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Telomerase TRAP assay

The standard two-step TRAP assay was modified for detecting N. crassa telomerase activity. In the first reaction, 1 µl of lysate or immunoprecipitated enzyme was mixed with 0.5 µM of TS primer (5′-AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTT-3′) in 1× primer extension (PE) buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM spermidine] containing 50 µM of dATP, dTTP and dGTP, and incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The TS primer was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The telomerase-extended products were PCR amplified in a 25-µl reaction consisting of 1× Taq buffer (NEB), 0.1 mM of dNTP, 0.4 µM of 32P end-labeled TS primer, 0.4 µM of ACX primer (5′-GCGCGGCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTAACC-3′), 0.4 µM of NT primer (5′-ATCGCTTCTCGGCCTTTT-3′), 4 × 10−13 M of TSNT primer (5′-CAATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTTAAAAGGCCGAGAAGCGATC-3′) and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (NEB). Samples were initially denatured at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 25–28 cycles at 94°C for 25 s, 50°C for 25 s and 68°C for 60 s, and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. PCR products were resolved on a non-denaturing 10% polyacrylamide/2% glycerol gel. The gel was dried, exposed to a phosphor storage screen and analyzed with a Bio-Rad FX-Pro Molecular Imager.

High-throughput sequencing and computational analysis

RNA extracted from purified N. crassa telomerase was used for cDNA library construction and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq2000 at Cofactor Genomics (St Louis, MO, USA). The 55-bp sequencing reads were analyzed by a computational pipeline including mapping the reads to the N. crassa reference genome and screening the assembled loci for putative template sequences. The sequencing reads were mapped with Segemehl (30), requiring a minimum accuracy rate of 85% and a maximum seed E-value of 10. Each read could maximally map to 100 distinct loci in the genome, with scoring only for maximal or multiple identical maximal hits. Ambiguous reads were corrected by hit normalization, whereby each read is divided by the number of matching loci. Candidate loci with an average hits-per-base more than five were subjected to the BLAST and open-reading-frame (ORF) analyses.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic comparative analysis

Filamentous ascomycete genome sequences obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute and Broad Institute were searched for NcrTER homologues by BLAST, with the E-value set between 1 × 10−3 and 1. The TER sequences were aligned with ClustalW (31) and manually refined using BioEdit v. 7.1.3. Initial sequence alignment was performed within each class and then expanded to include neighboring classes using highly conserved regions as anchor sites. Identification of nucleotide co-variations and inference of a secondary structure model were performed as previously described (5,32). The TER sequences identified from genome databases are available at the Telomerase Database (http://telomerase.asu.edu) (33).

Computational identification of S. complicata TER

S. complicata TER (ScoTER) was identified by searching for putative template and sequences conserved in the 73 filamentous ascomycete TERs. First, putative template sequences were identified in the S. complicata genome with Fragrep (34). For each occurrence, an additional 1-kb sequence upstream and 3-kb sequence downstream of the putative template were extracted. These 4-kb spans were then searched with Infernal 1.0 (35) for the TWJ region structure P6/6.1 (Supplementary Figure S2B) and with HMMer for a conserved pattern close to the 3′ end of the fungal TER sequences. The query patterns were obtained as follows: A co-variance model (CM) was constructed and calibrated with Infernal starting from the sequence alignment and the manually annotated consensus structure of the P6/6.1 region. In brief, CMs are generalizations of hidden Markov models (HMM) that evaluate not only sequence patterns but also complementary base pairings consistent with the prescribed consensus structure. The Pezizomycotina TER alignment of the highly conserved pseudoknot region was used to train an HMM using HMMer (36). A single sequence matching both the P6/6.1 CM and the pseudoknot HMM was identified.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)

The 5′ and 3′ ends of TERs from N. crassa, A. nidulans, M. graminicola and S. complicata were determined using the FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit following manufacture’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). For the 3′ RACE, total RNA was pre-treated with yeast poly(A) polymerase. Eight µg of total RNA was incubated with 500 units of yeast poly(A) polymerase (US Biological) in 1X reaction buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.6 mM MnCl2, 0.02 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT, 100 µg/ml acetylated BSA and 10% glycerol], 0.5 mM ATP and 1 unit/µl SUPERase IN (Life Technology) at 37°C for 15 min, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The PCR-amplified cDNAs were cloned and sequenced.

Telomerase in vitro reconstitution and direct primer-extension assay

Recombinant NcrTERT protein was in vitro synthesized in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) using the TnT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega) as previously described (37). In vitro transcribed full-length or truncated fragments of NcrTER were gel purified and assembled in RRL with the synthetic NcrTERT protein at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µM, respectively. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The telomerase primer-extension assay was carried out with 2 µl of in vitro-reconstituted telomerase in a 10-µl reaction in 1× PE buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.3), 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM spermidine], 1 mM dTTP, 1 mM dATP, 5 µM dGTP, 0.165 µM α-32P-dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/ml, PerkinElmer) and 1 µM telomeric primer (TTAGGG)3. The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 60 min and terminated by phenol/chloroform extraction, followed by ethanol precipitation. Telomerase-extended products were resolved on a denaturing 8 M urea/10% polyacrylamide gel. The dried gel was exposed to a phosphor storage screen and analyzed with a Bio-Rad FX Pro Molecular Imager.

The S. pombe telomerase was reconstituted in vitro and analyzed as described previously in the text, with minor modifications. A recombinant S. pombe TERT protein gene was synthesized de novo, with codons optimized for mammalian expression system (GenScript), and subcloned into the pCITE-4a vector (Promega). The recombinant S. pombe TERT protein was synthesized in RRL and assembled with 1 µM full-length or truncated fragments of S. pombe TER1 transcribed in vitro. The telomerase direct primer-extension assay was carried out with 2 µL of in vitro-reconstituted S. pombe telomerase in a 10 -µl reaction mixture containing 1× telomerase reaction buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermidine, 2 mM DTT], 0.2 mM dATP, dCTP and dTTP, 2 µM dGTP, 0.33 µM α-32P-dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/ml, PerkinElmer) and 5 µM DNA primer 5′-GTTACGGTTACAGGTTACG-3′.

Telomerase Pulse-chase analysis

Telomerase pulse-chase analysis was carried out using in vitro-reconstituted N. crassa telomerase and the telomerase direct primer-extension assay as described previously in the text. Before the pulse reaction, in vitro-reconstituted telomerase was incubated with 2 µM telomeric primer (TTAGGG)3 in 1× PE buffer at 20°C for 10 min. The pulse reaction was initiated by the addition of an equal-volume nucleotide mixture containing 1 mM dATP, 1 mM dTTP, 2 µM dGTP and 0.33 µM α-32P-dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer) and incubated at 20°C for 20s. The chase reaction was initiated by the addition of non-radioactive dGTP to 100 µM and the competitive primer (TTAGGG)3 with a 3′-blocking amine to 10 µM. Aliquots of the chase reactions were removed at various time points (2, 4, 6 and 8 min) and terminated by phenol/chloroform extraction, followed by ethanol precipitation. The products were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

Identification of N. crassa TER

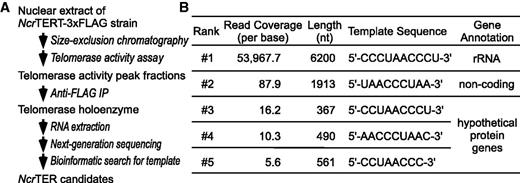

The filamentous ascomycete, N. crassa, is an important model organism with established genetics tools and a sequenced genome (26,38). We identified TER from N. crassa using a novel approach that combined a two-step purification of telomerase, deep-sequencing of co-purified RNA and computational analysis of sequencing data (Figure 2A). For telomerase purification, we generated a recombinant N. crassa strain that expressed NcrTERT protein with a C-terminal 3xFLAG tag (Supplementary Figure S1A and S1B). Nuclear extract prepared from the NcrTERT-3xFLAG strain was fractionated by gel filtration and assayed for telomerase activity by TRAP (Supplementary Figure S1C). Fractions with the highest telomerase activity were combined, and the NcrTERT protein was immunopurified with an anti-FLAG antibody (Supplementary Figure S1D). RNAs co-purified with the immunopurified NcrTERT-3xFLAG protein were extracted and analyzed by high-throughput Illumina next-generation sequencing, generating 15 million 55-bp reads. Nearly 90% of the reads were successfully assembled onto the N. crassa reference genome, and the assembled loci were screened for putative template sequences. The locus with the highest average coverage was a precursor ribosomal RNA (Figure 2B). This was not unexpected because ribosomal RNA is the most abundant RNA in the cell. The second highest ranked locus, our candidate TER, was ∼1900 nt long and lacked an apparent ORF. The exact 5′ and 3′ ends of this putative TER transcript were determined by the RNA ligase-mediated RACE (RLM-RACE) assays, which revealed the candidate TER to be 2049 nt in length, only slightly larger than the length of the locus covered by sequencing reads. The remaining loci were hypothetical protein-coding genes with insignificant read coverage (Figure 2B).

Identification of NcrTER by a deep-sequencing approach. (A) The multi-step strategy for N. crassa telomerase purification and NcrTER identification. Telomerase was purified from nuclear extract by size-exclusion chromatography and anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP). Telomerase activity was followed by TRAP assay through the purification steps. The RNA extracted from purified telomerase was sequenced using next-generation sequencing, followed by bioinformatics screening for putative template sequences. (B) The average read coverage, length, putative template sequence and gene annotation for the five top-ranking TER candidates. The candidates are ranked by the average read coverage.

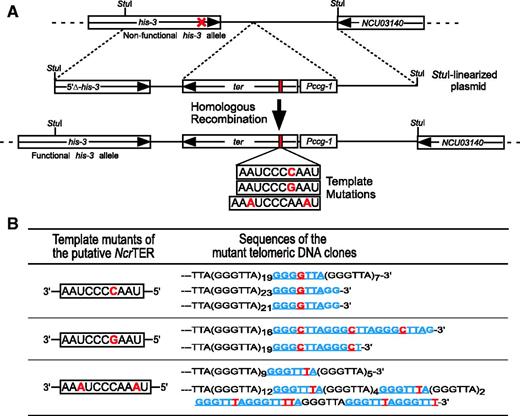

This 2049-nt N. crassa RNA was confirmed to be a functional TER by expression of template–mutated RNA genes in vivo resulting in the synthesis of corresponding mutant telomeric DNA sequences. Three N. crassa TER (NcrTER) mutant genes were integrated into the his-3 locus for ectopic expression in the cells (Figure 3A). Telomeric DNA from the template mutant strains was cloned and sequenced (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). For each template mutant, ∼20% of the telomeric DNA clones contained one or more corresponding mutant repeats. For example, the insertion of an additional cytosine residue in the template resulted in the insertion of an additional guanine residue in the telomeric DNA (Figure 3B). The mutant repeats were found at or near the 3′ end of the telomeric DNA, suggesting these mutant repeats were newly synthesized.

Validation of the NcrTER gene. (A) Schematic for generating NcrTER template mutants. The parental N. crassa strain NC1 had a loss-of-function mutation (red cross) in the his-3 allele. Mutant NcrTER genes driven by the ccg-1 promoter were integrated into the genome at the his-3 locus via homologous recombination. The template sequences of the three NcrTER mutants are presented, with the inserted nucleotides shown in red. (B) Expression of the NcrTER template mutants promotes synthesis of mutant telomeric repeats. Sequences of mutant telomeric DNA repeats (blue) are shown, with the inserted nucleotides (red) highlighted.

Secondary structure of NcrTER core domains

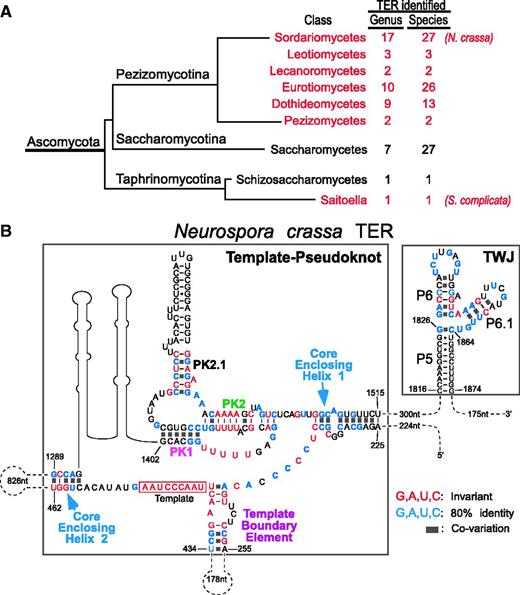

To predict the secondary structure of NcrTER by phylogenetic comparison analysis, we identified homologous TER sequences from 72 Pezizomycotina species by BLAST of available fungal genome databases using the NcrTER sequence as query (Figure 4A and supplementary Table S2). In addition to Pezizomycotina, we identified the TER in S. complicata from the distantly related Taphrinomycotina subphylum through an advanced bioinformatics approach that searches for both sequence and structural patterns (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). The standard BLAST search failed to identify S. complicata TER from the genome owing to the great evolutionary distance between Pezizomycotina and Taphrinomycotina. The length of representative Pezizomycotina and Taphrinomycotina TERs (A. nidulans, M. graminicola and S. complicata) were determined by RACE analysis (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, the M. graminicola TER with a size of 2425 nt was found to be the largest TER yet identified.

Secondary structure model of the NcrTER core domains. (A) Number of fungal TER sequences identified. In this study, 73 new TER sequences were identified from six Pezizomycotina classes (red) and one Taphrinomycotina TER sequence from S. complicata. The number of TER sequences identified in each class is indicated. Branch length is not proportional to evolutionary distance. (B) Secondary structure model of the NcrTER core domains: the template–pseudoknot and the TWJ that includes the P5, P6 and P6.1 stems. Invariant nucleotides (red) or nucleotides with ≥80% identity (blue) as well as base pairings supported by co-variations (solid gray boxes) are indicated. Other major structural features shown include the core-enclosing helices 1 and 2, template boundary element, template and the pseudoknot helices PK1, PK2 and PK2.1. The regions without secondary structure determined are indicated by dotted lines, with the number of omitted residues indicated.

Secondary structures of two NcrTER core domains were inferred by phylogenetic comparative analysis of the newly identified Pezizomycotina TER sequences and supported by nucleotide co-variations (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). The two NcrTER core domains, the template–pseudoknot and the TWJ, are highly conserved across Pezizomycotina species and presumably homologous to vertebrate and budding yeast TER structures (Figure 4B). The NcrTER template–pseudoknot domain consists of the template, a template boundary element, a pseudoknot structure and two core-enclosing helices that bring the pseudoknot and template close to each other (Figure 4B). The pseudoknot structure is formed by two helices, termed PK1 and PK2, with an additional helix PK2.1 inserted in the loop between. From the core-enclosing helix 2 to the pseudoknot, two additional helices are predicted by mfold, but these base-paired structures lack strong nucleotide co-variation support. The NcrTER TWJ domain is highly conserved across Pezizomycotina species and shares striking similarity to the vertebrate CR4/CR5 domain (Figure 4B). Based on the structural homology to vertebrate TER, we named the three helices of N. crassa TWJ domain P5, P6 and P6.1. Compared with the budding yeast TWJ, which usually contains long helices, the Pezizomycotina TWJ contains short P6 and P6.1 stems, similar to the fish P6 and P6.1 stems, which are only 9 bp and 4 bp long, respectively (39). The regions beyond these two core domains are too variable in sequence to be properly aligned outside individual classes and are thus not included in the phylogenetic sequence analysis. Preliminary structure prediction in these variable regions using the mfold software did not reveal any structures similar to the Est1 or Ku protein-binding sites reported previously in budding yeast TERs. Examination of the TER primary sequences also did not reveal any canonical Sm protein-binding site. However, direct experimentation is necessary to determine the presence or absence of these accessory proteins in N. crassa telomerase holoenzyme.

N. crassa telomerase requires both template–pseudoknot and TWJ domains for activity

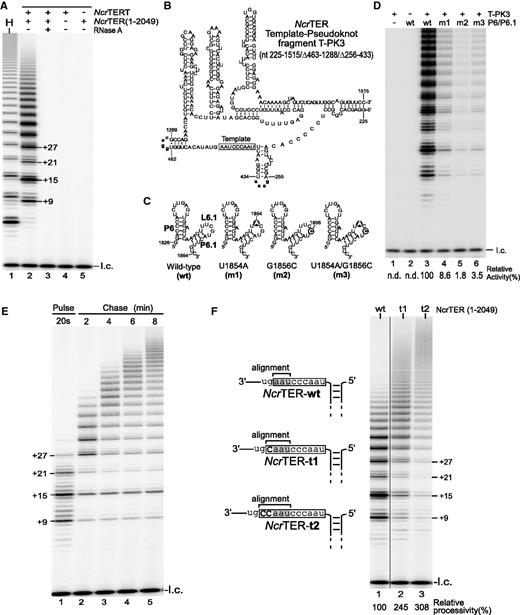

N. crassa telomerase reconstituted in vitro was analyzed by direct primer-extension assay and exhibited typical telomerase activity, adding multiple repeats to the primer 5′-(TTAGGG)3-3′ to generate a 6-nt ladder pattern with major bands at positions +9, +15, +21, +27 nt etc. (Figure 5A, lane 2). This activity required both NcrTER and NcrTERT components, and was RNase sensitive (Figure 5A, lanes 3–5). From the same primer, the human telomerase generated a pattern with major bands at positions +4, +10, +16, +22 nt etc. (Figure 5A, lane 1). The offset patterning arises from the NcrTER template 3′-AAUCCCAAU-5′ having a 5′-boundary one nucleotide offset compared with the human TER template 3′-CAAUCCCAAUC-5′. This is the first fungal telomerase successfully reconstituted in vitro from full-length synthetic TER.

Functional characterization of N. crassa telomerase activity. (A) Direct primer-extension assay of in vitro-reconstituted N. crassa telomerase. Recombinant NcrTERT protein was synthesized in RRL and assembled with 0.1 µM full-length 2049-nt NcrTER. The reconstituted N. crassa telomerase was analyzed by direct primer-extension assay using the telomeric primer (TTAGGG)3. The major bands (+9, +15, +21 and +27) are denoted on the right of lane 2, indicating the number of nucleotides added to the primer. Addition of RNase A (lane 3), the absence of NcrTER (lane 4) and the absence of NcrTERT (lane 5) is indicated above the gel. Human telomerase (H) served as a positive control (lane 1). A 32P-end-labeled 15-mer oligonucleotide was included as loading control (l.c.) before purification and precipitation of telomerase-extended products. (B) Secondary structure of the minimal 295-nt NcrTER template–pseudoknot fragment T-PK3. The T-PK3 fragment contains nucleotides 225–1515, with two internal deletions (nt 256–433 and 463–1288) replaced with tetraloops (bold, lower case), GAAA and GGAC, respectively. The template region is denoted by an open box. (C) The 39-nt NcrTER P6/6.1 RNA fragments with L6.1 mutations. Point mutations, U1854A (m1), G1856C (m2) and U1854A/G1856C (m3), in the L6.1 loop are indicated by solid circles (D). Mutations in loop L6.1 severely reduced telomerase activity. N. crassa telomerase was reconstituted in RRL from the recombinant NcrTERT protein and two separate RNA fragments, T-PK3 and P6/6.1, and were analyzed by direct primer-extension assay. The RNA fragments assayed within each reaction are denoted above the gel. Relative telomerase activity is shown under the gel (lane 4–6) and was determined by normalizing the total intensities of all bands within each lane to wild-type activity in lane 3. The relative activity was not determined (n.d.) for lanes 1 and 2. A 32P-end-labeled 15-mer oligonucleotide was included as the loading control (l.c.). (E) Pulse-chase time course analysis of N. crassa telomerase. In vitro-reconstituted telomerase was incubated with telomeric primer (TTAGGG)3 for 20 s at room temperature in the presence of radioactive α-32P-dGTP, dTTP and dATP. An aliquot of the reaction was removed and terminated after 20 s to determine the initial length of the product (lane 1). Chase reaction was initiated by adding 50 folds of non-radioactive dGTP and 10 folds of competitive DNA oligonucletide 5′-(TTAGGG)3-3′-amine. Aliquots of the chase reaction was removed and terminated after 2, 4, 6 or 8 min from the start of the chase reaction (lane 2–5). A 15-mer 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide was added as loading control (l.c.). (F) Effect of template length on repeat addition processivity. Full-length NcrTER (1–2049) with either the wild-type 9-nt template (wt), 10-nt template (t1) or 11-nt template (t2) was reconstituted with NcrTERT protein in RRL and analyzed by direct primer-extension assay. The NcrTER template sequence is denoted by an open box, with the alignment region shaded. Relative processivity was determined by normalization to wild-type processivity and is shown below the gel. A 15-mer 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide was included as loading control (l.c.).

Vertebrate and yeast telomerases differ in the RNA domains required for enzymatic function. In vertebrate telomerases, both the TER template–pseudoknot and the CR4/5 domains are essential for enzymatic activity, and can assemble in trans with the TERT protein (15,16,40). In contrast, S. cerevisiae telomerase can be reconstituted from a miniature TER lacking TWJ, indicating that the yeast TWJ is dispensable for enzymatic activity (41). Unlike S. cerevisiae and more similar to vertebrates, N. crassa required both the TER template–pseudoknot and TWJ domains for enzymatic activity and these two TER domains assembled in vitro with the TERT protein in trans as two separate RNA fragments (Supplementary Figure S3). We identified an NcrTER minimal core essential for activity by serial truncations and functional assay. Full activity can be reconstituted from a miniature 295-nt template–pseudoknot core, named T-PK3, and a 39-nt TWJ fragment of only the joined P6 and P6.1 stem-loops without P5 (Figure 5B and 5C; Supplementary Figure S3C, lanes 6–9). This is similar to the vertebrate CR4/5 domain, of which only P6 and P6.1 stem-loops, but not the P5 stem, are required for activity (42,43). Thus, N. crassa telomerase preserves the vertebrate-like functional attribute, requiring two distinct RNA domains for activity.

The NcrTER P6.1 stem-loop, identical to vertebrate P6.1, contains a conserved 4-bp stem and a 5-nt loop with the consensus sequence 5′-NUNGN-3′ (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S2B). In vertebrate telomerase, the conserved uridine and guanosine residues in the loop are crucial for telomerase function (13,44). To examine the importance of the NcrTER L6.1 loop for telomerase activity, we introduced single mutations, U1854A (m1) and G1856C (m2), and a double mutation, U1854A/G1856C (m3), into the minimal P6/6.1 NcrTER fragment (nt 1826–1864) and assayed the reconstituted mutant enzymes for activity (Figure 5C). All three mutations dramatically reduced telomerase activity (Figure 5D, lanes 3–6), suggesting that the N. crassa L6.1 is crucial to telomerase activity and functionally homologous to vertebrate L6.1.

N. crassa telomerase is processive

To determine whether the N. crassa telomerase is truly processive, adding multiple repeats to the same primer by the same enzyme, we performed a pulse-chase time course assay with the N. crassa telomerase reconstituted in vitro. The pulse primer (TTAGGG)3 pre-bound to the telomerase enzyme was first ‘pulsed’ in the presence of radioactive α-32P-dGTP for 20 s and then ‘chased’ in the presence of 50-fold non-radioactive dGTP and 10-fold chase primer for 2, 4, 6 or 8 min. This assay detects processive elongation of only the initial ‘pulsed’ products by the same enzyme during the chase reaction. During the pulse reaction, 3–4 repeats were added to the primer (Figure 5E, lane 1). These ‘pulsed’ products were progressively elongated during the chased reaction time course, indicating processive repeat addition by the same enzyme (Figure 5E, lanes 2–5). Therefore, we concluded that N. crassa telomerase is processive in repeat addition.

N. crassa telomerase appeared to have lower repeat addition processivity than human telomerase, possibly from the shorter alignment region in the NcrTER template (Figure 5A, lanes 1 and 2). In vertebrate telomerase, extending the alignment region in the template increases repeat addition processivity (45). We thus generated and analyzed two template-extended NcrTER mutants, NcrTER-t1 and -t2, to determine the effect of the extended alignment region on repeat addition processivity. As seen previously with human and mouse telomerases (45), the repeat addition processivity of the NcrTER template mutants was increased 2- to 3-fold, compared with the wild-type enzyme (Figure 5F).

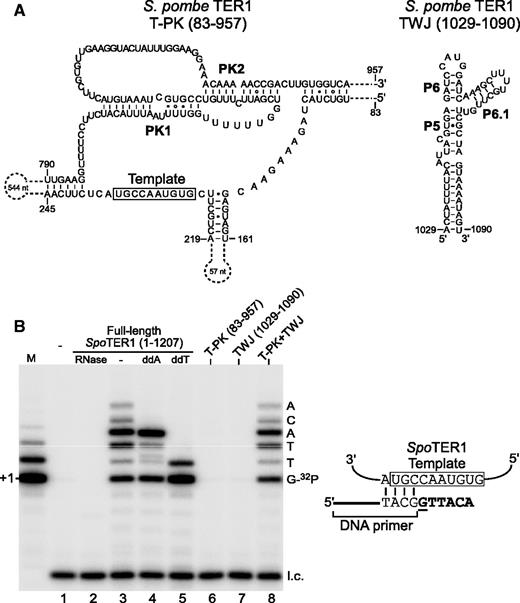

S. pombe telomerase also requires two RNA domains for activity

In addition to Pezizomycotina TER, both S. pombe and S. complicata TERs also preserve the same pseudoknot and TWJ core domains (Figure 6A). Specifically, the S. pombe and S. complicata TWJ structures contain the vertebrate-like 4-bp P6.1 stem and a 4- to 5-nt L6.1 loop (Figure 6A, Right). To determine whether the S. pombe TWJ domain is functionally homologous to vertebrate TWJ, we first established an in vitro reconstitution system for S. pombe telomerase core enzyme and later examined whether a physically separate S. pombe TWJ RNA fragment added in trans can reconstitute telomerase activity. The S. pombe telomerase core enzyme was reconstituted in RRL from the recombinant S. pombe TERT protein and the synthetic full-length 1207-nt S. pombe TER1 (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section), and analyzed for activity by primer-extension assay (Figure 6B). The activity reconstituted required S. pombe TER1 and was sensitive to RNase A treatment, suggesting a ribonucleoprotein enzyme (Figure 6B, Left, lanes 1–3). The nucleotide addition reaction terminated at expected positions when dideoxyadenosine triphosphate (ddATP) or dideoxythymidine triphosphate (ddTTP) was present, indicating a template-dependent reaction (Figure 6B, Right). The products extended by the in vitro-reconstituted S. pombe telomerase showed a strong band at the +4 position, a pattern similar to the activity from in vivo-reconstituted telomerase previously reported by Baumann group (46). We then tested whether the S. pombe TWJ domain (nt 1029–1090), which included helices P5, P6 and P6.1, could reconstitute telomerase activity in trans with the template–pseudoknot domain (nt 83–957). Similar to N. crassa and vertebrate TERs, S. pombe telomerase required both the template–pseudoknot and TWJ domains for reconstituting wild-type level of activity (Figure 6B, lanes 6–8). Therefore, the vertebrate-like P6/6.1 motif of the TWJ is crucial for telomerase activity and is conserved across vertebrates, Pezizomycotina and Taphrinomycotina.

Reconstitution of S. pombe telomerase activity from two separate RNA fragments. (A) The secondary structure model of S. pombe TER1 core domains. The template–pseudoknot (T-PK) is composed of nt 83–957 and the TWJ is from nt 1029–1090. (B) Left, direct primer-extension assay of in vitro-reconstituted S. pombe telomerase. Telomerase was reconstituted in RRL from recombinant S. pombe TERT protein and 1 µM T7-transcribed TER1 RNA (Full-length: 1–1207; T-PK: 83–957 or TWJ: 1029–1090). The addition of ddATP and ddTTP in place of dATP and dTTP, respectively, in the reactions is indicated. RNase A (RNase) was added to the reaction in lane 2. A DNA size marker (M) was generated by labeling the 3′ end of the DNA oligonucleotide (5′-GTTACGGTTACAGGTTACG-3′) with α-32P-dGTP using TdT. A 15-mer 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide was included as loading control (l.c.). The expected sequence of nucleotides incorporated is shown on the right of the gel. Right, Alignment of the DNA primer sequence with the template sequence of S. pombe TER1. The previously determined template region is denoted by an open box (46). Nucleotides added to the DNA primer are shown in bold, with the radioactive 32P-dGTP underlined.

DISCUSSION

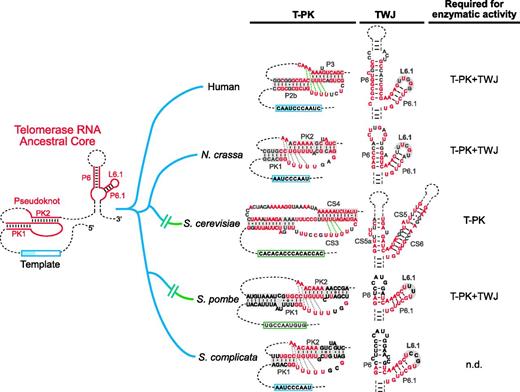

TER is evolutionarily divergent in size, sequence and structure, posing an obstacle in discerning structural commonalities and evolutionary connections among organisms. In this study, we showed that fungal TERs from Pezizomycotina and the early-branching Taphrinomycotina retain vertebrate-like structural features and functional attributes: a common RNA core that includes the vertebrate-like pseudoknot and P6/6.1 stem-loop, as well as the requirement of both RNA elements for enzymatic activity (Figure 7). In contrast, budding yeast TER has diverged substantially from other ascomycete TERs, exhibiting structural variations in both the pseudoknot and TWJ domains, requiring only the template–pseudoknot domain for enzymatic activity.

Conservation and diversification of the common ancestral core of vertebrate and fungal TERs. Left, a minimal consensus structure of TER depicts the core domains common to both vertebrate and fungal TERs. Right, secondary structure models of TER pseudoknot and TWJ cores from human, N. crassa, S. cerevisiae, S. pombe and S. complicata are shown, with their evolutionary relationships depicted. Nucleotides shown in red indicate ≥80% identity within vertebrates, Saccharomyces and filamentous ascomycete, or identical between S. pombe and S. complicata. Sequences omitted are denoted as dashed lines. The helical regions in the pseudoknot structure and the highly conserved loop L6.1 in the TWJ domain are shaded gray. The predicted and experimentally determined base triples in the pseudoknot are indicated by gray and green dashed lines, respectively. The RNA core domains required for reconstituting telomerase activity in vitro are indicated for individual species.

The TER pseudoknot structure, although universally present, shows substantial variations in size and complexity among ciliates, fungi and vertebrates (47,48). The TER pseudoknot is minimally defined by two quasi-continuous helices, PK1 and PK2, connected by two loops (Figure 7). Within the vertebrate and non-yeast pseudoknot, the PK1 and PK1 helices are contiguous with no unpaired residues at the junction point. In contrast, budding yeast pseudoknots contain several unpaired residues at the helical junction. In the human TER pseudoknot, the upstream loop is highly conserved, consisting of 4–5 invariant uridine residues that form a triple helix with the PK2 helix through base triple interactions (9). Similar base triples have also been reported in ciliate and budding yeast pseudoknots, suggesting a universal and crucial role of this unique triple-helix pseudoknot for telomerase function (11,12). The downstream loop is highly variable in sequence, often harboring large insertions that can potentially form additional helical elements. In vertebrate and budding yeast pseudoknots, no conserved helical structures have been determined by phylogenetic comparison or mutagenesis analysis in this variable region. The N. crassa pseudoknot is unique in that a conserved helix PK2.1 was identified in the variable loop by phylogenetic comparative analysis (Figure 4B). The functional significance of the N. crassa helix PK2.1, however, remains to be determined.

The P6/6.1 stem-loop element in the TWJ is essential for telomerase enzymatic activity and is highly conserved in vertebrates, the filamentous fungus N. crassa and the fission yeast S. pombe, but not in budding yeasts (Figure 7). In both vertebrates and N. crassa, the TERT protein recognizes minimally the two linked P6/6.1 stem-loops, rather than requiring the complete TWJ structure (42,43). The variable P5 stem appears to function merely to connect the P6/P6.1 stem-loops to the remainder of the TER. In the vertebrate telomerase ribonucleoprotein (RNP), the P6/6.1 stem-loop binds tightly and specifically to the TRBD of TERT protein, potentially facilitating TERT folding (42). Although lacking a vertebrate-like L6.1 loop, the K. lactis TWJ contains an asymmetric U-rich internal loop that has been proposed to function similarly to L6.1 (14). However, budding yeast telomerase has evolved to not rely on the TWJ for enzymatic function (10,41). The binding interface between the vertebrate P6/6.1 element and the TRBD of vertebrate TERT has been mapped using ultraviolet (UV) cross-linking analysis (42). Analysis of the yeast TWJ–TERT binding interface would help determine the extent of structural and functional homology between vertebrate and yeast TWJ structures.

Repeat addition processivity is a telomerase-specific mechanistic attribute conserved widely in ciliates and vertebrates. In this study, we show that N. crassa telomerase is highly processive in vitro, synthesizing the vertebrate-type TTAGGG from a 1.5-repeat template in the TER (Figure 5E). However, despite the significant repeat addition processivity observed with in vitro-reconstituted telomerase, the telomeric DNA cloned from N. crassa strains expressing template mutants contains up to three consecutive mutant repeats (Figure 3B). This limited addition of mutant repeats could result from telomere length regulation restricting processive repeat addition in vivo or potentially deleterious effects of long mutant repeats to the cell survival. While the detailed mechanism remains unknown, telomerase repeat addition processivity requires highly coordinated actions of numerous telomerase-specific TERT motifs, such as motif 3, IFD, CTD and TEN domain, and a realignment region in the template sufficient for template translocation. Impairment of any of these elements has been shown to drastically reduce repeat addition processivity (37,45,49,50).

Telomerases from specific vertebrate and fungal species appear to have lost repeat addition processivity during the course of evolution from alterations in either the template or the TERT motifs. For example, mouse telomerase is non-processive owing to the shortened template, which is unable to undergo efficient primer–template realignment during template translocation (45,51). Increasing the TER template length significantly increases repeat addition processivity as previously shown with mouse telomerase (45) and in this study with N. crassa telomerase (Figure 5F). Conversely, telomerases from many budding yeast models, such as S. cerevisiae, K. lactis and Candida albicans, synthesize irregular or long telomere repeats non-processively (7,52,53). For example, K. lactis telomerase synthesizes the TGGTGTACGGATTTGATTAGGTATG repeat from a 30-nt-long template, which possibly hinder template translocation. Nonetheless, the budding yeast Saccharomyces castellii telomerase appears to have retained repeat addition processivity, suggesting the loss of processivity in S. cerevisiae telomerase is a relatively recent evolutionary event (53).

The conservations of the vertebrate-like pseudoknot and an essential P6/6.1 element and processive synthesis of TTAGGG repeats suggest that N. crassa telomerase preserves more structural features and functional attributes of vertebrate telomerases, than budding yeast telomerases. While our understanding of telomerase and telomere biology has benefited greatly from yeast models, N. crassa is an exciting new model for the study of telomerase function and telomere biology. Understanding the common mechanisms of telomerase action shared between distantly related organisms will potentially provide new insights into telomere-mediated diseases, cancer and potential therapies.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

GenBank Accession number: JF794773, JQ793886, JQ793887, JQ793888, JX173807.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Figures 1–3.

FUNDING

National Science Foundation (NSF) [CAREER award MCB0642857 to J.J.-L.C.]; National Institutes of Health [GM025690 to E.U.S.]; DFG [MA5082/1-1 to M.M., STA-850/7-2 to P.F.S.]. Funding for open access charge: NSF.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr Stephen Marek for providing the genomic DNA of Phymatotrichum omnivorum (OKAlf8), and Dr Gert Kema for providing M. graminicola. We acknowledge the Fungal Genetic Stock Center and the ARS Culture Collection (NRRL) for providing materials.

Comments