Abstract

BACKGROUND: Patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) have more difficulty communicating with health care providers and are less satisfied with their care than others. Both interpreter- and language-concordant clinicians may help overcome these problems but few studies have compared these approaches.

OBJECTIVE: To compare self-reported communication and visit ratings for LEP Asian immigrants whose visits involve either a clinic interpreter or a clinician speaking their native language.

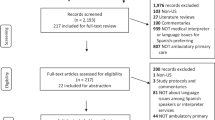

DESIGN: Cross-sectional survey—response rate 74%.

PATIENTS: Two thousand seven hundred and fifteen LEP Chinese and Vietnamese immigrant adults who received care at 11 community-based health centers across the U.S.

MEASUREMENTS: Five self-reported communication measures and overall rating of care.

RESULTS: Patients who used interpreters were more likely than language-concordant patients to report having questions about their care (30.1% vs 20.9%, P<.001) or about mental health (25.3% vs 18.2%, P=.005) they wanted to ask but did not. They did not differ significantly in their response to 3 other communication measures or their likelihood of rating the health care received as “excellent” or “very good” (51.7% vs 50.9%, P=.8). Patients who rated their interpreters highly (“excellent” or “very good”) were more likely to rate the health care they received highly (adjusted odds ratio 4.8, 95% confidence interval, 2.3 to 10.1).

CONCLUSIONS: Assessments of communication and health care quality for outpatient visits are similar for LEP Asian immigrants who use interpreters and those whose clinicians speak their language. However, interpreter use may compromise certain aspects of communication. The perceived quality of the interpreter is strongly associated with patients’ assessments of quality of care overall.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000. U.S. Census Bureau; 2000.

Hu DJ, Covell RM. Health care usage by Hispanic outpatients as function of primary language. West J Med. 1986;144:490–3.

Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Katz SJ, Welch HG. Is language a barrier to the use of preventive services? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:472–7.

Gandhi TK, Burstin HR, Cook EF, et al. Drug complications in outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:149–54.

Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:409–17.

Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:82–7.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Hablamos Juntos: We Speak Together. 2002.

Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Coates WC, Pitkin K. Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department. JAMA. 1996;275:783–8.

Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36:1461–70.

Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:468–74.

Lee LJ, Batal HA, Maselli JH, Kutner JS. Effect of Spanish interpretation method on patient satisfaction in an urban walk-in clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:641–5.

Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26:1119–28.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans’ reports of their health care experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:111–9.

Collins KS, Hughes D, Doty MS, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K. (The Commonwealth Fund). Diverse Communities Common Concerns: Assessing the Health Quality for Minority Americans. 2002.

Murray-Garcia JL, Selby JV, Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Quesenberry CP Jr. Radical and ethnic differences in a patient survey: patients’ values, ratings and reports regarding physician primary care performance in a large health maintenance organization. Med Care. 2000;38:300–10.

Taira DA, Safran DG, Seto TB, et al. Asian-American patient ratings of physician primary care performance. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:237–42.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Kaplan SH, Sorkin DH, Clarridge BR, Phillips RS. Surveying minorities with limited-English proficiency: does data collection method affect data quality among Asian Americans? Med Care. 2004;42:893–900.

Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S, Roberts M, et al. Patients evaluate their hospital care: a national survey. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10:254–67.

Consumer Assessment of Health Plans (CAHPS). Fact Sheet. AHRQ Publication No. 00-PO47. Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagli MP, Clarridge BR, et al. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:44–52.

SAS SAS Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 8.1 for Windows. Cary, NC: SAS; 1999.

SUDAAN. Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data [computer program]. Version 7.5.6 for Windows. Research Triangle Park, NC: SUDAAN; 2002.

Rivadeneyra R, Elderkin-Thompson V, Silver RC, Waitzkin H. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. Am J Med. 2000;108:470–4.

Fagan MJ, Diaz JA, Reinert SE, Sciamanna CN, Fagan DM. Impact of interpretation method on clinic visit length. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:634–8.

Kravitz RL, Helms LJ, Azari R, Antonius D, Melnikow J. Comparing the use of physician time and health care resources among patients speaking English, Spanish, and Russian. Med Care. 2000;38:728–38.

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296–306.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583–9.

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O II. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302.

Karliner LS, Perez-Stable EJ, Gildengorin G. The language divide. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:175–83.

Carrillo JE, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural primary care: a patient-based approach. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:829–34.

Laws MB, Heckscher R, Mayo SJ, Li W, Wilson IB. A new method for evaluating the quality of medical interpretation. Med Care. 2004;42:71–80.

Massachusetts General Hospital. Medical interpreter services. Available at: http://www.mgh.harvard.edu/interpreters/working.asp. Accessed July 1, 2004.

Poss JE, Rangel R. Working effectively with interpreters in the primary care setting. Nurse Pract. 1995;20:43–7.

Betancourt JR, Carrillo JE, Green AR. Hypertension in multicultural and minority populations: linking communication to compliance. Curr Hypertension Rep. 1999;1:482–8.

Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer A, Perez-Stable EJ. Interpersonal processes of care in diverse populations. Milbank Quart. 1999;77:305–39, 274.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001.

Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111:6–14.

Perez-Stable EJ, Napoles-Springer A, Miramontes JM. The effects of ethnicity and language on medical outcomes of patients with hypertension or diabetes. Med Care. 1997;35:1212–9.

Jacobs EA, Agger-Gupta N, Chen AH, Piotrowski A, Hardt EJ. (The California Endowment). Language Barriers in Health Care Settings: An Annotated Bibliography of the Research Literature. 2003.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. National Standards of Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office; 2000.

Vandervort EB, Melkus GD. Linguistic services in ambulatory clinics. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14:358–66.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Physician perspectives on communication barriers: insights from focus groups with physicians who treat non-English proficient and limited-English proficient patients. 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study was funded by the Agency for Health care Research and Quality, Grant no. RQ R01-HS10316 and the Commonwealth Fund, Grant no. 20020110. Dr. Green received support from a National Research Service Award, Grant no. T32 HP11001-15. Dr. Phillips is supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award no. K24 AT00589-03 from the National Institutes of Health.

Role of Sponsor: The funding organizations took no part in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or review or approval of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Green, A.R., Ngo-Metzger, Q., Legedza, A.T.R. et al. Interpreter services, language concordance, and health care quality. J GEN INTERN MED 20, 1050–1056 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0223.x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0223.x