Abstract

Aim

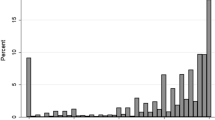

The discounted utility (DU) model has dominated economic evaluation for almost 7 decades, despite the fact that important assumptions of the model are commonly found to be violated. This paper formally explores whether the key assumption of stationarity is violated in a sample of the general population of Northern Tanzania. Furthermore, three hyperbolic discounting models are fitted to the data, and whether they perform better than the DU model in predicting individuals’ time preferences is tested using nonlinear least squares regression. Method: The data were collected from 450 households by trained enumerators. The individual data on time preferences were collected by structured interviews using an open-ended stated preference methodology. Respondents marked a rating scale to indicate the maximum number of days they would be willing to suffer a nonfatal disease if the outbreak of the disease could be delayed to a point further into the future. Households were randomised to answer questions framed to elicit either a private or social time preference.

Results

Hypothesis testing confirmed decreasing time aversion and a magnitude effect, suggesting that the DU model is inappropriate as a descriptive tool. When the DU model was compared with the three hyperbolic discounting models by analysing the discount factor using nonlinear least squares regression, the most important findings were that a variable for starting point was nonsignificant only for the Loewenstein and Prelec (L & P) and the Mazur models, and that people in this setting generally discounted future health far more than suggested by current discounting practice in economic evaluations.

Conclusion

The time preferences of our sample are better represented by the L & P and the Mazur models (which allow relaxation of the stationarity assumption through a modification of the expression for the discount factor) and less well reflected by the Harvey (a modification of the L & P model that assigns more importance to the future than standard utility discounting) and DU models. This implies that, from the point of view of a consumer sovereignty-friendly economist, the Mazur and the L & P models are preferable for discounting of future health in economic evaluations. However, from the point of view of other value bases for discounting the choice of discounting model is of less importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Harvey[14] provides the following example to illustrate how sensitive the weights for the distant future are to small changes in discount rate between two early adjacent periods: IfD(1)= (1 + ρ) −1 is increased from (1.10) −1 to (1.05) −1, a relative increase of about 5%, then D(100)=(1 + ρ) −100 is increased from (14 000) −1 to (130) −1, a relative increase of about 10 000%.

References

Dolan P, Olsen JA. Distributing health care: economic and ethical issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002

Loewenstein G, Prelec D. Anomalies in intertemporal choice: evidence and an interpretation. Q J Econ 1992; 107 (2): 573–597

Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O, T. Time discounting and time preference: a critical review. J Econ Lit 2002; 40 (2): 351–401

Samuelson P. A note on measurement of utility. Rev Econ Stud 1937; 4: 155–161

Bleichrodt H, Johanneson M. Time preference for health: a test of stationarity versus decreasing timing aversion. J Math Psychol 2001; 45: 265–282

Cairns J. Discounting in economic evaluation. In: Drummond M, McGuire A, editors. Economic evaluation in health care: merging theory with practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001: 236–255

Cairns J, van der Pol MM. Saving future lives: a comparison of three discounting models. Health Econ 1997; 6: 341–350

van der Pol M, Cairns J. A comparison of the discounted utility model and hyperbolic discounting models in the case of social and private intertemporal preferences for health. J Econ Behav Org 2002; 49 (1): 79–96

Cairns J, van der Pol M. Constant and decreasing timing aversion for saving lives. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45 (11): 1653–1659

Cairns J, van der Pol M. Valuing future private and social benefits: the discounted utility model versus hyperbolic discounting models. J Econ Psychol 2000; 21: 191–205

Strotz RH. Myopia and inconsistency in dynamic utility maximization. Rev Econ Stud 1955; 23 (3): 165–180

Cairns JA, van der Pol M. The estimation of marginal time preference in a UK-wide sample (TEMPUS) project. Health Technol Assess 2000; 4 (1): 1–83

Prelec D. Decreasing impatience: a criterion for nonstationary time preference and “hyperbolic” discounting. Scand J Econ 2004; 106 (3): 511–532

Harvey CM. Value functions for infinite-period planning. Manag Sci 1986; 32 (9): 1123–1139

Poulos C, Whittington D. Individuals’ time preferences for lifesaving programs: results from six less developed countries. Singapore: Economy and Environment Program for South East Asia (EEPSEA). International Development Research Centre, Regional Office for Southeast and East Asia, 1999: 1–20

Robberstad B. Estimation of private and social time preferences for health in northern Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61 (7): 1597–1607

Pol Mvd, Cairns J. Methods for eliciting time preferences over future health events. In: Scott T, Maynard A, Elliott B, editors. Advances in health economics. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2003: 41–58

StataCorporation. Stata base reference manual, vol. 1–4. College Station (TX): Stata Press Publication, 2003

Wooldridge JM. Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Mason (OH): Thomson South-Western, 2003

Abeyasekera S, Ward P. Models for predicting expenditure per adult equivalent (for AMMP surveillance sentinel sites). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Adult Morbidity and Mortality Project (AMMP), Ministry of Health, 2002: 43

Kennedy P. A guide to econometrics. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998

Greene WH. Econometric analysis. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall, 2003

Verbeek M. A guide to modern econometrics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2000

Loewenstein G, Prelec D. Negative time preference. Am Econ Rev 1991; 81 (2): 347–352

Pol Mvd, Cairns JA. Negative and zero time preference for health. Health Econ 2000; 9: 171–175

Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge (MA): Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002

WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003

Koopmans TC. Stationary ordinal utility and impatience. Econometrica 1960; 28: 287–309

Robberstad B. Economic evaluation of health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: applied economic evaluations and studies on time preferences for health in Tanzania. Bergen: University of Bergen, 2005

Phelps ES, Pollak R. On second-best national saving and game equilibrium growth. Rev Econ Stud 1968; 35: 185–199

Bleichrodt H, Doctor J, Stolk E. A nonparametric elicitation of the equity-efficiency trade-off in cost-utility analysis. J Health Econ 2005; 24 (4): 655–678

Miller MA, McCann L. Policy analysis of the use of hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type B, Streptococcus pneumoniae-conjugate and rotavirus vaccines in national immunization schedules. Health Econ 2000; 9: 19–35

Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge (MA): The Harvard School of Public Health, 1996

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without excellent co-operation with the Adult Mortality and Morbidity Project (AMMP), National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH) and the regional, district and village authorities in Tanzania. Data collection was possible because of tremendous efforts from Jonathan Moye, Amini R. Lema, Julie J. Tarimu, Violet Kiwelu, Gabriel Masuki, Yusuf Hemed and David Whiting. The paper benefited from discussions with Espen Bratberg, Gaute Torsvik, Ole Frithjof Norheim, Jan Abel Olsen and Marjon van der Pol. Finally, we are indebted to the 450 households in Hai district who welcomed us and voluntarily spent time answering all those tricky questions. The research was financed by the Norwegian Research Council. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robberstad, B., Cairns, J. Time Preferences for Health in Northern Tanzania. Pharmacoeconomics 25, 73–88 (2007). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200725010-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200725010-00007