Abstract

Background: Obesity is a major contributor to the overall burden of disease (also reducing life expectancy) and associated with high medical costs due to obesity-related diseases. However, obesity prevention, while reducing obesity-related morbidity and mortality, may not result in overall healthcare cost savings because of additional costs in life-years gained. Sector-specific financial consequences of preventing obesity are less well documented, for pharmaceutical spending as well as for other healthcare segments.

Objective: To estimate the effect of obesity prevention on annual and lifetime drug spending as well as other sector-specific expenditures, i.e. the hospital segment, long-term care segment and primary healthcare.

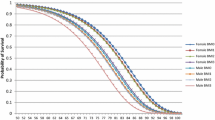

Methods: The RIVM (Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) Chronic Disease Model and Dutch cost of illness data were used to simulate, using a Markov-type model approach, the lifetime expenditures in the pharmaceutical segment and three other healthcare segments for a hypothetical cohort of obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2), non-smoking people with a starting age of 20 years. In order to assess the sector-specific consequences of obesity prevention, these costs were compared with the costs of two other similar cohorts, i.e. a ‘healthy-living’ cohort (non-smoking and a BMI ≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2) and a smoking cohort. To assert whether preventing obesity results in cost savings in any of the segments, net present values were estimated using different discount rates. Sensitivity analyses were conducted across key input values and using a broader definition of healthcare.

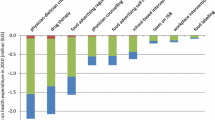

Results: Lifetime drug expenditures are higher for obese people than for ‘healthy-living’ people, despite shorter life expectancy for the obese. Obesity prevention results in savings on drugs for obesity-related diseases until the age of 74 years, which outweigh additional drug costs for diseases unrelated to obesity in life-years gained. Furthermore, obesity prevention will increase long-term care expenditures substantially, while savings in the other healthcare segments are small or non-existent. Discounting costs more heavily or using lower relative mortality risks for obesity would make obesity prevention a relatively more attractive strategy in terms of healthcare costs, especially for the long-term care segment. Application of a broader definition of healthcare costs has the opposite effect.

Conclusions: Obesity prevention will likely result in savings in the pharmaceutical segment, but substantial additional costs for long-term care. These are important considerations for policy makers concerned with the future sustainability of the healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One study that does use a lifetime approach similar to the one followed by van Baal et al.[13] is the previously mentioned study by Allison et al.[11] These authors concluded that obesity prevention may lead to cost savings. Van Baal et al.[13] offer several possible explanations for their different findings.

It is important to note that prevention may sometimes increase total healthcare expenditure due to an increase of related medical costs that are induced in life-years gained alone.[19]

Consumers may buy supplementary healthcare insurance from private health insurers for care that is not covered by either of the two Acts, i.e. care that is covered in the third compartment (e.g. cosmetic surgery and physiotherapy).

For example, smoking increases the chance of getting lung cancer, which subsequently increases the risk of dying. As a consequence, the life expectancy of smokers in the model is lower than the life expectancy of non-smokers.

The obese cohort is modelled as non-smokers to facilitate a clear interpretation of the substitution of diseases and its associated costs. Moreover, due to interactions between both risk factors with regard to mortality, it would pose additional data demands.

Other definitions of healthcare costs available in the Netherlands are the Dutch Health and Social Care Accounts used by Statistic Netherlands (CBS) and the Budgetary Scheme of Care used by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. The first definition takes the broadest, societal perspective including some welfare costs and, for example, costs of housing and day nursery, while the latter includes costs that fall under the ministerial responsibility.

Note that we focus here on the consequences of prevention for healthcare costs, not on the costs of prevention itself. Therefore, we assume that the preventive intervention that would lead to this eradication (i.e. completely preventing obesity), is costless. Obviously, such interventions are hard to come by.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of the WHO consultation of obesity. WHO Technical Report Series 894. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000

Abelson PH, Kennedy D. The obesity epidemic [editorial]. Science 2004; 304: 1413

World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. Factsheet N 311 [online]. Available from URL: (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html) [Accessed 2008 Dec 12]

Kelly T, Yang W, Chen C-S, et al. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1431–7

Visscher TLS, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001; 22: 355–75

Haslam DW, James WPT. Obesity. Lancet 2005; 366: 1197–209

Hu FB. Obesity epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008

Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009; 373: 1083–96

Neovius M, Sundström J, Rasmussen F. Combined effects of overweight and smoking in late adolescence on subsequent mortality: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2009; 338: b496

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Health at a glance. Paris: OECD, 2005

Allison DB, Zannolli R, Narayan V. The direct health care costs of obesity in the United States. Am J Public Health 1999; 89: 1194–9

Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, et al. Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 2177–83

van Baal PHM, Polder JJ, de Wit GA, et al. Lifetimemedical costs of obesity: prevention no cure for increasing health expenditure. PLoS Med 2008; 5 (2): e29

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, et al. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 2003; 289: 187–93

Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a lifetable analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138: 24–32

Olshanksy SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1138–45

Barendregt JJ, Bonneux L, van der Maas PJ. The health care costs of smoking. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1052–7

Sloan FAOJ, Picone G, Conover C, et al. The price of smoking. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press, 2004

Hoogenveen RT, Verkleij H, Jager JC. Investigation into the substitution of mortality and the impact of competing risks in case of quantitative health targets [in Dutch]. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), 1990

Spilman BC, Lubitz J. The effect of longevity on spending for acute and long-term care. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1409–15

Slobbe ICJ, Kommer GJ, Smit JM, et al. Cost of illness in the Netherlands [in Dutch]. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), 2006

Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport (VWS). Health insurance in the Netherlands: the new health insurance system from 2006. The Hague: VWS, 2005

Van de Ven WPMM, Schut FT. Universal mandatory health insurance in The Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Aff 2008; 27: 771–81

Schut FT, van de Ven WPMM. Rationing and competition in the Dutch health-care system. Health Econ 2005; 14: S59–74

Council for Public Health and Health Care (RVZ). The labour market and demand for care [in Dutch]. The Hague: RVZ, 2006

Collins RW, Anderson JW. Medication cost savings associated with weight loss for obese non-insulin-dependent diabetic men and women. Prev Med 1995; 24: 369–74

Greenway FL, Ryan DH, Bray GA, et al. Pharmaceutical cost savings of treating obesity with weight loss medications. Obes Res 1999; 7: 523–31

Narbro K, Ågren G, Jonsson E, et al. Pharmaceutical costs in obese individuals: comparison with a randomly selected population sample and long-term changes after conventional and surgical treatment. The SOS intervention study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 2061–9

Ågren G, Narbro K, Näslund I, et al. Long-term effects of weight loss on pharmaceutical costs in obese subjects: a report from the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes 2002; 26: 184–92

Hoogenveen RT, van Baal PHM, Boshuizen HC. Chronic disease projections in heterogeneous aging populations: approximating multi-state models of joint distributions by modelling marginal distributions. Math Med Biol. Epub 2009 Jun 10

Van Baal PHM, Hoogenveen RT, de Wit GA, et al. Estimating health-adjusted life expectancy conditional on risk factors: results for smoking and obesity. Popul Health Metr 2006; 4: 14

Struijs JN, van Genugten ML, Evers SM, et al. Modeling the future burden of stroke in The Netherlands: impact of aging, smoking, and hypertension. Stroke 2005; 36: 1648–55

Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, Bos G, Bemelmans WJ, et al. Lifestyle interventions are cost-effective in people with different levels of diabetes risk: results from a modeling study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 128–34

World Health Organization (WHO) expert consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363: 157–63

National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Cost of illness in the Netherlands [online]. Available from URL: (http://www.costofillness.eu) [Accessed 2009 Sep 8]

Meerding WJ, Bonneux L, Polder JJ, et al. Demographic and epidemiological determinants of health care costs in the Netherlands: cost of illness study. BMJ 1998; 317: 111–5

World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of diseases, injuries and causes of death, 9th revision. Geneva: WHO, 1977

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). A system of health accounts. Version 1.0. Paris: OECD, 2000

Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ). Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic research, updated version. Diemen: CVZ, 2006

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russel LB, et al., editors. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996

Smith DH, Gravelle H. The practice of discounting in economic evaluations of healthcare interventions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2001; 17: 236–43

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 2005

Reuser M, Bonneux LG, Willekens FJ. The burden of mortality of obesity at middle and old age is small: a life table analysis of the US Health and Retirement Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2008; 23: 601–7

Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA 2005; 293: 1861–7

Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. JAMA 1999; 282: 1530–8

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004; 291: 1238–45

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2005; 293: 293

Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Pickard L, et al. Cognitive impairment in older people: future demand for long-term care services and the associated costs. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 22: 1037–45

Yang Z, Norton EC, Stearns SC. Longevity and health care expenditures: the real reasons older people spend more. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003; 58 (1): S2–10

Van Baal PHM, van den Berg M, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Cost effectiveness of a low-calorie diet and orlistat for obese persons: modelling long term health gains through prevention of obesity- related chronic diseases. Value Health 2008; 11: 1033–40

Bemelmans WJE, van Baal PHM, Wendel-Vos WV, et al. The costs, effects and cost-effectiveness of counteracting overweight on a population level. Prev Med 2008; 46: 123–32

Van Baal PHM, Brouwer WBF, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Increasing tobacco taxes: a cheap tool to increase public health. Health Policy 2007; 28: 142–52

Van Baal PHM, Feenstra TL, Hoogenveen RT, et al. Unrelated medical care in life years gained and the cost utility of primary prevention: in search of a ‘perfect cost-utility ratio’. Health Econ 2007; 16: 421–33

Brouwer WBF, van Exel NJA, van Baal PHM, et al. Economics and public health: engaged to be happily married! Eur J Public Health 2007; 17: 122–3

Cutler DM, Rosen AB, Vijan S. The value of medical spending in the United States, 1960-2000. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 920–7

Narbro K, Ågren G, Jonsson E, et al. Sick leave and disability pension before and after treatment for obesity: a report from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999; 23: 619–24

Vissher TLS, Rissanen A, Seidell JC, et al. Obesity and unhealthy life-years in adult Finns: an empirical approach. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 1413–20

Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Wyatt HR, et al. Productivity costs associated with cardiometabolic risk factor clusters in the United States. Value Health 2007; 10: 443–50

Neovius M, Kark M, Rasmussen F, et al. Association between obesity status in young adulthood and disability pension. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1319–26

Meltzer D. Accounting for future costs in medical costeffectiveness analysis. J Health Econ 1997; 16: 33–64

Seidell JC. Epidemiology and health economics of obesity. Medicine 2006; 34: 506–9

Polder JJ, Takkern J, Meerding WJ, et al. Cost of illness in the Netherlands [in Dutch]. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), 2002

Rappange DR, Brouwer WBF, Rutten FFH, et al. Lifestyle intervention: from cost savings to value for money. J Public Health. Epub 2009 Aug 7

Acknowledgements

This study was part of the project ‘Living longer in good health’, which was financially supported by Netspar. The opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors.

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rappange, D.R., Brouwer, W.B.F., Hoogenveen, R.T. et al. Healthcare Costs and Obesity Prevention. Pharmacoeconomics 27, 1031–1044 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/11319900-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11319900-000000000-00000