Published online Nov 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6569

Revised: June 1, 2008

Accepted: June 8, 2008

Published online: November 14, 2008

Gastrointestinal tract involvement by neurofibromatous lesions is rare and occurs most frequently as one of the systemic manifestations of generalized neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). In this setting, the lesions may manifest as focal scattered neurofibromas or as an extensive diffuse neural hyperplasia designated ganglioneuromatosis. Occasionally, such lesions may be the initial sign of NF1 in patients without any other clinical manifestations of the disease. Rarely, cases of isolated neurofibromatosis of the large bowel with no prior or subsequent evidence of generalized neurofibromatosis have been documented. We present the case of a 52 year-old female with abdominal pain and alternating bowel habits. Colonoscopic evaluation revealed multiple small polyps in the cecum and the presence of nodular mucosa in the colon and rectum. Pathologic evaluation of the biopsies from the cecum, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum revealed tangled fascicles of spindle cells expanding the lamina propia leading to separation of the intestinal crypts. Immunohistochemical stains helped confirm the diagnosis of diffuse intestinal neurofibromatosis. A thorough clinical evaluation failed to reveal any stigmata of generalized neurofibromatosis. This case represents a rare presentation of isolated intestinal neurofibromatosis in a patient without classic systemic manifestations of generalized neurofibromatosis and highlights the need in such cases for close clinical follow-up to exclude neurofibromatosis type I or multiple endocrine neoplasia type II.

- Citation: Carter JE, Laurini JA. Isolated intestinal neurofibromatous proliferations in the absence of associated systemic syndromes. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(42): 6569-6571

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i42/6569.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6569

Neurofibromatous lesions of the lower gastrointestinal tract may manifest in multiple forms and have accordingly been given various descriptive designations including intestinal neurofibromatosis, ganglioneuromatosis, diffuse plexiform neurofibromatosis, neuronal intestinal dysplasia, and diffuse colonic ganglioneuromatous polyposis. These lesions may be seen in up to 25% of cases of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b (MEN 2b), and their occurrence in the absence of other clinical features of NF1 and MEN 2b is extremely rare[1]. Neurofibromatous lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, unassociated with systemic features of NF1 or MEN 2b, have also been documented in distributions isolated to the esophagus and stomach[2]. No consensus has yet been reached in the medical community as to whether these isolated lesions represent different phenotypic manifestations of the neurocutaneous and multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes or whether they represent separate and distinct entities.

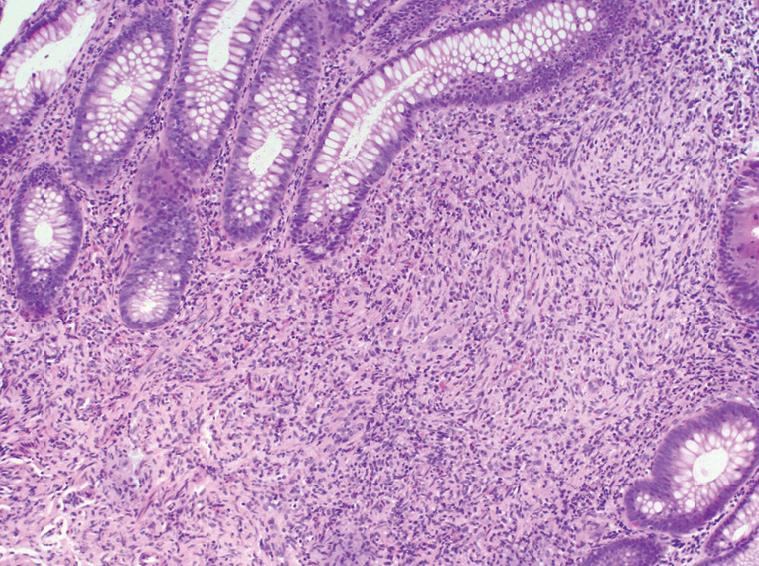

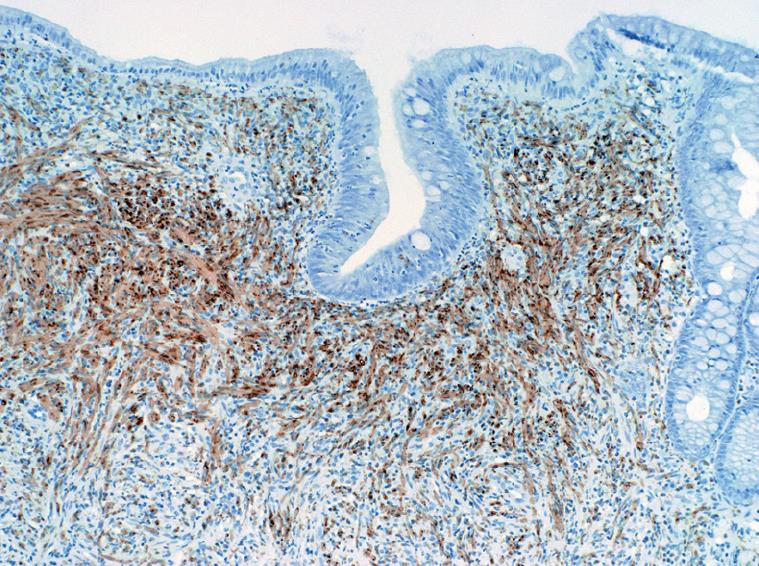

A 51-year-old female presented to our institution with a three-year history of worsening gastroesophageal reflux. She stated that she had progressively developed dysphagia to solid foods and had begun to regurgitate solid food particles, but the episodes of vomiting were unassociated with nausea, epigastric pain, or abdominal pain. The patient denied weight loss and reported no improvement of her symptoms with smaller meals. For the last year, the patient also reported the development of frequent non-bloody diarrhea with associated abdominal cramping and bloating. There was no history of coffee-ground emesis, hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. The patient’s additional past medical history included Sjogren’s syndrome, fibromyalgia, and cervical radiculitis. The patient had previously undergone colonoscopy with biopsy at a separate institution. At that time, multiple small polyps of the cecum and a 5-8 cm segment of mucosal nodularity of the descending colon were identified. Biopsies of the cecum and colon were diagnosed histologically as hyperplastic changes and as an inflammatory fibroid polyp. At our institution, the patient was placed on a lactose-free diet due to suspected lactose intolerance, but over the course of three months, she experienced an 8 lb. (3.63 kg) weight loss and continuing gastrointestinal distress. A subsequent colonoscopy again showed multiple cecal polyps and nodular large bowel mucosa. Biopsies were obtained from the cecum, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. Histologic analysis of the biopsies showed a proliferation of tangled fascicles of spindle cells admixed with scattered chronic inflammatory cells expanding the lamina propria and leading to separation of the intestinal crypts (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains for S-100 protein supported the diagnosis of neurofibroma for each of the biopsies (Figure 2). The biopsy specimens from the patients’ prior colonoscopy were obtained from the outside institution, and immunohistochemical analysis confirmed a retrospective diagnosis of neurofibromas. A thorough physical examination failed to reveal any clinical signs of neurofibromatosis or multiple endocrine neoplasia. Following her diagnosis of isolated intestinal neurofibromatosis, the patient was lost to clinical follow-up in our healthcare system.

Isolated intestinal neurofibromatous proliferations (IINP) are benign neural lesions of the lower gastrointestinal tract which may be the initial manifestation of generalized systemic NF1 or MEN 2b. In these settings, IINP may manifest as single or multiple well-defined stromal neoplasms or as a diffuse neuronal hyperplasia, commonly termed ganglioneuromatosis. The clinical, radiographic, and histologic findings of such lesions are not specific to NF1 or MEN 2b, and identical features have been reported in association with juvenile and adenomatous colonic polyposis[3,4] and as an isolated finding in patients with no additional clinical evidence of neurocutaneous, intestinal polyposis, or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes[5,6].

The clinical presentation of neurofibromatous lesions of the lower gastrointestinal tract are myriad and are dependent upon the focal or diffuse nature of the lesions, their location, their effect on gastrointestinal motility, and their possible impingement on adjacent structures. Affected patients may present with altered bowel habits including constipation or diarrhea[7,8], abdominal pain[9], intestinal obstruction[10], or with palpable abdominal masses[6]. In the setting of NF1, associated clinical findings including the classic dermal neurofibromas, café-au-lait macules, and Lisch nodules may be seen. In the setting of MEN 2b, the characteristic facies including thickened lips from mucosal neuromas, marfanoid habitus, and even features of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid may be present. In IINP, the intestinal symptoms manifest without demonstrable clinical evidence of associated systemic syndromes.

Radiographically, lower gastrointestinal neurofibro-matous lesions may manifest as diffuse, confluent thickening of portions of the intestine or as single or multiple discrete lesions of the intestinal wall or mesentery. The radiographic differential diagnosis of single or multiple nodular neurofibromatous lesions is wide and includes many epithelial and stromal neoplasms as well as nodular lymphomas. The diffuse forms of IINP may mimic the radiographic appearance of Crohn’s

disease on barium studies and computed tomography scans. In a report by Charagundla et al[7], a patient with signs and symptoms of colitis was found to have segmental thickening of an extended portion of the distal ileum radiographically. Clinically, Crohn’s disease was suspected, but subsequent small bowel resection showed diffuse IINP. At least two other reports have documented similar findings[11,12].

The endoscopic appearance of IINP depends on the focal or diffuse nature of the lesions. As the lesions arise deep to the epithelium, they manifest as single or multiple subepithelial masses of variable size and distribution. In some cases, numerous small lesions carpet a portion of the lower gastrointestinal tract, while in others, a larger lesion may predominate and significantly stenose the lumen of the affected area. Endoscopic biopsies are the mainstay of diagnosis, but when used in an attempt to sample deep-seated lesions, the biopsies may yield only unaffected overlying bowel mucosa or minimally diagnostic superficial lesional tissue. Ulceration, due to erosion of the epithelium over the surface of lesions, has been described, particularly in larger solitary lesions, but occasional cases have been described in which ulceration was sufficiently widespread and significant to raise the endoscopic differential diagnosis of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. In the current case, the endoscopic appearance was that of multiple small cecal polyps and nodular colonic mucosa, and endoscopic sampling yielded only the most superficial portion of the neurofibromatous proliferation. No associated ulceration was identified.

Grossly, the intestinal neurofibromatous proliferations tend to be firm, solid, and white to tan throughout. Hemorrhage and necrosis are exceptional, but superficial ulceration has been reported in lesions of varying size. The lesions may manifest as confluent neurofibromatous proliferations involving contiguous sections of bowel or as focal polypoid lesions with a sporadic distribution. The varied gross manifestations of IINP generally have a similar histologic appearance, consisting of a proliferation of neural elements including nerve fibers and supporting cells which may be diffusely intermingled or arranged in fascicles of bland spindle-shaped cells. The cells exhibit elongated nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Ganglion cells may be present in variable numbers. Despite their sometimes striking cellularity and occasional cellular pleomorphism, mitotic activity in these lesions is minimal. Immunohistochemically, the cells show a variable degree of expression for S100 protein and synaptophysin.

IINP most frequently involve the colon, terminal ileum, and appendix[13], but similar neurofibromatous proliferations isolated to the upper gastrointestinal tract have been described. Siderits et al[2] reported a case of sporadic ganglioneuromatosis of the gastroesophageal junction in a patient with gastroesophageal reflux, and solitary neurofibromas of the esophagus have also been documented[14]. These lesions show endoscopic and biopsy features identical to their counterparts in the lower gastrointestinal tract.

The treatment of IINP is primarily surgical and is dependent on the location and size of the lesions. Solitary, well-circumscribed lesions may be only incidental findings at the time of screening endoscopy and require no further therapy, but larger solitary lesions may come to clinical attention due to intestinal obstruction or impingement on adjacent structures and require resection. For lesions that are more diffusely distributed, treatment strategies are dictated by the symptomatology. Intractable abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea may require palliative resection of the involved segment of lower gastrointestinal tract. Accurate histopathologic categorization of biopsy and resection specimens is required to guide appropriate surgical therapy.

Peer reviewer: Ian C Roberts-Thomson, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 28 Woodville Road, Woodville South 5011, Australia

S- Editor Zhong XY E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Hochberg FH, Dasilva AB, Galdabini J, Richardson EP Jr. Gastrointestinal involvement in von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Neurology. 1974;24:1144-1151. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Siderits R, Hanna I, Baig Z, Godyn JJ. Sporadic ganglioneuromatosis of esophagogastric junction in a patient with gastro-esophageal reflux disorder and intestinal metaplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7874-7877. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Mendelsohn G, Diamond MP. Familial ganglioneuromatous polyposis of the large bowel. Report of a family with associated juvenile polyposis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:515-520. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Weidner N, Flanders DJ, Mitros FA. Mucosal ganglioneuromatosis associated with multiple colonic polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:779-786. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Bononi M, De Cesare A, Stella MC, Fiori E, Galati G, Atella F, Angelini M, Cimitan A, Lemos A, Cangemi V. Isolated intestinal neurofibromatosis of colon. Single case report and review of the literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:737-742. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Hirata K, Kitahara K, Momosaka Y, Kouho H, Nagata N, Hashimoto H, Itoh H. Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis with plexiform neurofibromas limited to the gastrointestinal tract involving a large segment of small intestine. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:263-267. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Charagundla SR, Levine MS, Torigian DA, Campbell MS, Furth EE, Rombeau J. Diffuse intestinal ganglioneuromatosis mimicking Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1166-1168. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Kim HR, Kim YJ. Neurofibromatosis of the colon and rectum combined with other manifestations of von Recklinghausen's disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1187-1192. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Boldorini R, Tosoni A, Leutner M, Ribaldone R, Surico N, Comello E, Min KW. Multiple small intestinal stromal tumours in a patient with previously unrecognised neurofibromatosis type 1: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evaluation. Pathology. 2001;33:390-395. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Urschel JD, Berendt RC, Anselmo JE. Surgical treatment of colonic ganglioneuromatosis in neurofibromatosis. Can J Surg. 1991;34:271-276. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Urbano U, Farina P. [Intestinal ganglioneuromatosis in a case of terminal ileitis]. Pathologica. 1967;59:547-550. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Tobler A, Maurer R, Klaiber C. [Stenosing ganglioneuromatosis of the small intestine with ileus and ileal rupture]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1981;111:684-688. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Shekitka KM, Sobin LH. Ganglioneuromas of the gastrointestinal tract. Relation to Von Recklinghausen disease and other multiple tumor syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:250-257. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Lee R, Williamson WA. Neurofibroma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1173-1174. [Cited in This Article: ] |